From the Desk of Gus Mueller

From the Desk of Gus Mueller

Last month here at 20Q Ian Windmill talked about the future of audiology. He reviewed several internal and external forces that might be changing the profession and the way we practice. But most importantly, he emphasized that we cannot simply remain in place, but rather we need to extend our reach, and consider the opportunities these potential developments have. We’re going to address one of these opportunities this month at 20Q, and talk about interventional audiology.

Interventional audiology? Probably not a term you’ve used often, or maybe at all. It is new to audiology, but certainly not to medicine, where there are journals and societies dedicated to this topic. As reviewed by Catherine Palmer, PhD in a webinar here at AudiologyOnline last year, interventional audiology often means managing hearing loss in order to impact other primary health concerns, which means interaction with other health care providers. In many cases, hearing loss is neither the person’s nor the other health care provider’s primary concern. It requires us to think a little different about how we provide our services. But this is just one example.

To bring us the big picture of interventional audiology, we’re going to bring in someone who has been writing about it for several years, Brian Taylor, AuD. He is the director of clinical research for HyperSound, and a consultant for Fuel Medical Group. In addition, he is the Editor of Audiology Practices, the quarterly journal for the Academy of Doctors of Audiology, and also serves as an instructor for the AuD program at A.T. Still University.

You might know Dr. Taylor for his workshops, or his more than 50 publications related to the selection, fitting and dispensing of hearing aids. He also has been busy writing books—five at last count—with a second edition of the popular Fitting & Dispensing Hearing Aids soon to be released.

Brian tells us that if it wasn’t for the modern laptop computer with Microsoft Word, he’d probably be a farmer or a logger—the two most popular professions in his bucolic hometown of Holcombe, Wisconsin. That takes us to yet another of his current professional ventures, serving as the Editor of The Hearing News Watch for the weekly blog Hearing Healthcare & Technology Matters. Many of his recent postings are related to the looming changes that are at the heart of interventional audiology. As you’ll see in this month’s 20Q, Brian effectively shows that the keyboard can be mightier than either the pitchfork or the chainsaw.

Gus Mueller, PhDContributing Editor

May 2016

To browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller CEU articles, please visit www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: Interventional Audiology - Changing the Way We Deliver Care

Learning Objectives

- Participants will be able to describe interventional audiology and the components of an interventional approach to audiology services.

- Participants will be able to explain the factors that will likely change the delivery of audiology services in the future.

- Participants will be able to list two ways they can begin preparing to adapt an interventional audiology approach in their practice.

Brian Taylor

1. Interventional audiology? I’m not too sure exactly what that is?

Well, it can be a lot of different things. In general, when we use the term interventional audiology, we are referring to direct involvement with people who have hearing loss or self-reported difficulties with their hearing. Rather than centering our services around a device to treat hearing loss, interventional audiology looks at hearing loss in the broader context of its relationship to other medical conditions. Through interventional audiology, we seek to promote a healthy lifestyle and improve health outcomes. In many instances, this involves changing the way we think about patient care, and often requires looking at patient care from an inter-professional standpoint. Or, looking at different ways to provide services.

2. I’ve recently heard about the PCAST guidelines. Is that something that fits under the interventional audiology umbrella?

You are referring to the recommendations of the Presidential Counsel of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) that are based on the meetings that were held a few months ago. Most of our readers are probably familiar with these recommendations, but briefly, the guidelines suggested that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) do four things:

- Create a new, direct-to-consumer category of hearing aids for mild-to-moderate hearing losses.

- Withdraw its draft guidance that personal sound amplification products (PSAPs) be marketed only to people with normal hearing.

- The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) require that clinicians provide customers with audiograms and “audio profile” at no charge.

- The FTC should define a process authorizing hearing aid vendors to have the ability to obtain the patient’s test results at no additional change to the consumer.

The FDA met a few weeks ago to discuss some of these recommendations. They heard opinions and analysis from many key stakeholders, including representatives from industry and professional organizations, hearing instrument specialists, audiologists, engineers and consumer advocates. It’s too early to know whether or not they will alter current hearing aid regulations, but it’s fair to say there are strong arguments on both sides.

Regardless of the outcome, this is a really broad topic, and in order to appreciate the full scope of the recommendations of groups like PCAST, let’s first step back and examine some fundamental shifts in our society and their implications to the profession of audiology. You’re probably familiar with the apocryphal expression, “may you live in interesting times.” Well, I think we are at the beginning of a memorable journey filled with many opportunities to better meet the needs of adults coping with the consequences of hearing loss.

3. I’m curious, what exactly do you mean by interesting times?

I’m referring to the way many of us were taught to practice audiology and dispense hearing aids – placing an ad in the local newspaper or yellow pages, waiting for patients to find their way to the clinic, testing and then fitting them with hearing aids, and providing face-to-face services over the course of several years. Each of these steps is likely to drastically change over the next decade.

But don’t misunderstand me, I think there will always be a place for the traditional approach to delivering audiology-related services. In fact, reliable sources predict the market for traditional hearing aids will continue to enjoy strong growth over the next five years. But, with the evolution of technology and the changing wants and needs of consumers, there are likely to be some remarkable changes in how we practice over the next decade or two.

4. How do you know they'll be changes in audiology practice in the future - do you have a crystal ball?

You don’t need to be a mystic; all you have to do is pay attention to the broader field of healthcare to believe this transformation is not unique to audiology. Like all realms of healthcare, audiology is moving from a paternalistic approach, in which patients were passive participants in a boilerplate approach to care, to a consumer-driven system where there’s an abundance of treatment options and delivery models available. In the near future, successful audiology practices are likely to be defined by what consumers –individuals with self-reported hearing difficulties, many with hearing loss – want, not by the tests, assessments and hearing aid fittings we produce.

5. Why is this change occurring?

There are four, largely interconnected reasons that help explain this sea of change. The first is the aging population. According to the Pew Research Center, 10,000 people every day will turn 65 for the next 15 years. This is a global challenge and it’s unprecedented, and it means that we will have a growing number of people in need of services to address their hearing and communication needs. Baby boomers have greatly changed many industries as they have aged. They were the first generation to grow up watching television and quickly businesses realized they could use mass marketing to sell them products. Think about all those classic jingles, like “Have a Coke and a Smile” or commercials featuring Ronald McDonald & the Hamburglar. They were viewed by millions of Baby boomers and eventually their children back when there were just three television networks. We are talking the largest generation in human history being wooed by Madison Avenue advertising executives – it’s a generation that’s been raised to be constantly entertained, to think a little differently than previous generations; that it’s okay to be a little roguish and playful.

6. I’m not too sure what all that has to do with audiology, and besides, a doubling of the number of older people over the next 20 years is great for my business. Why should I do anything different?

Stick with me; I think it will start to make more sense. Two decades ago, when boomers started to turn 45 years of age, more than 76 million Americans over the next 20 years needed reading glasses. This enormous group of similarly aged people was accustomed to having immediate access to many choices. Over the years, the Baby boomers orientation to the marketplace – actively seeking out new solutions, questioning authority - has had a huge impact on several businesses, including the optical industry. Because boomers, unlike previous generations, were apt to be directly involved in their healthcare, we saw the growth of over-the-counter reading glasses (e.g., cheaters). That change didn’t happen because the optical industry simply wanted to be nice to this group; it happened because the market demanded it and a few entrepreneurs capitalized on the opportunity to provide an alternative device and a new way to distribute their product.

7. But we’ve had a large group of people around in their 60s and early 70s for decades? Why is it different now?

Let me elaborate. It’s not the age per se of such a large swath of people -all born between 1945 and 1963 – that makes them so different than previous generations of aging adults. The Baby boomer generation is the first ever to live their entire lives in the era of modern advertising and modern medicine – with childhood vaccinations and antibiotics, with infection control and other evidence-based medical practices that mitigated and even eliminated threatening afflictions. Unlike previous generations that often had first-hand experiences with infant and childhood death, collectively, Baby boomers have experienced outstanding health from birth. They learned quickly that they could take a pill, get a shot or make a quick visit to the doctor and their malady would be cured. In turn, a by-product of the wonders of modern medicine was to heighten expectations with respect to healthcare. Baby boomers represent the leading edge of a more demanding, actively engaged consumer called healthy agers.

8. What is the difference between a boomer and an ager?

They often are the same person. The rise of the healthy aging movement can be explained through the lens of living an entire lifespan in the world of modern medicine. When people live a relatively healthy life they expect to stay healthy and active as they age. Healthy agers are individuals who want to live to be 100, but maintain the vitality of a 45-50 year old. More than just a chronological age, healthy agers comprise a broad group of adults who want to take a more active role in their health care.

Baby boomers, healthy agers, however you describe them, are a huge group of people, many of which are about to retire, which brings me to another very important point. Another key factor driving change in our profession is the skyrocketing cost of healthcare. There are dozens of reasons why American healthcare costs are high, but the Baby boomers play a role. Since so many of them are retiring relative to the population of younger generations, there will be an increased cost burden associated with taking care of them as they age.

According to National Institutes of Health (NIH), more than half of the total healthcare costs in the US are consumed by just 5% of the population. It’s a reasonable assumption that the vast majority of this 5% are older Americans who have several co-existing chronic conditions. And, although no one knows exactly, it’s a good bet that many of them, given their age and overall health, have some degree of hearing loss. If cost continues to grow, the current model is unsustainable. Even though the federal government has been trying to use legislation to contain costs, many healthcare organizations are beginning to address the cost by introducing new approaches to care. We are beginning to see the rise of groups called Accountable Care Organizations and Integrated Healthcare Systems that incentivize primary care physicians to practice preventive medicine. The bottom line with many of these new systems is they are trying to do a better job of coordinating care across medical specialties as well as foster greater patient engagement (that is, getting patients more directly involved in advocating for their long term health). All of these new terms are lumped into the rubric of population-based healthcare. As we maybe can talk about later, the rise of population-based healthcare offers great opportunities for audiologists to be more proactively involved with hearing screening and other types of interventional audiology.

9. I’m starting to understand your earlier definition of interventional audiology.

The term interventional may be new to audiology, but it’s familiar to physicians. For years there have been interventional cardiologists and radiologists. Physical therapists can even specialize in interventional methods. What all interventional methods have in common is that they use the least invasive techniques available to minimize risk to the patient and improve health outcomes of patients with chronic conditions. An interventional cardiologist, for example, would earnestly avoid performing open heart surgery on patients and would want to identify an at-risk condition early and treat the condition with diet and exercise, if that less invasive treatment is supported by good evidence. Bob Tysoe has been using the term interventional audiology for years and we wrote a couple of articles in the Hearing Review (Taylor & Tysoe, 2013; 2014). And, Catherine Palmer presented a webinar on the topic at AudiologyOnline (Palmer, 2015). Since age-related hearing loss has been reported to be the third most common chronic medical condition in older adults, interventional audiologists would support early screening and other less invasive approaches to management of age-related hearing loss.

10. Before we get too far into interventional audiology, you said there were four factors that could change the way we practice, but you only named only three - what's the fourth?

Yes, thanks for reminding me, there is an additional factor. It’s the incremental improvement of technology. Any audiologist who has fit hearing aids over the past 20 years lives in a world of incrementally improving technology. Every 18 months or so, hearing aid manufacturers launch a new product. Spurred by Moore’s Law, all computer-based technology is continually getting faster, smarter, more automated and cheaper to manufacture. The ceaseless march-of-technological-improvement undoubtedly affects audiology in a couple of ways. First, we are seeing self-fitting hearing aids and automated audiometry being introduced into the clinical arena. Besides being cool, these technological advances potentially enable the non-professional - even a computer housed in a kiosk - to conduct much of the testing, selecting and fitting of hearing aids without sacrificing precision. Second, technically savvy consumers and advocates for the hearing impaired see the cost of laptop computers, cell phones and other consumer electronic products getting less expensive. They question why hearing aids, which are often marketed as sophisticated consumer electronic devices, are not dropping in price by the same amount. Finally, just about everyone, including octogenarians, can jump on the Internet to comparison shop and buy things. The Internet is giving people more choices over what to buy and pay attention to.

An aging population that wants to live actively for 90 to 100 years, coupled with inexpensive, ever-improving technology and unsustainable healthcare costs, will all have an impact on how audiology is practiced.

11. That all makes sense. So, back to the direct impact on my practice?

One way to think about the evolving role of audiology in the larger context of healthcare is to view age-related hearing loss as a triple threat. Historically, audiologists have dealt with just one of them: Age-related hearing loss is a disability in its own right, which directly leads to activity limitations and participation restrictions. Individuals who have been living with hearing loss for more than a few years are likely to miss out on routine conversations with friends or miss the dialogue in a pivotal scene of their favorite television program. These are the patients we typically expect to enter the doors of our clinics.

12. I understand all this . . . what are the other “threats?”

I think of them as upstream and downstream consequences. An upstream consequence of untreated, age-related hearing loss is that it interferes with a patient’s ability to be treated for other medical conditions, mainly because it hinders an individual’s ability to engage with physicians and understand treatment advice and directives. Recent studies showed that individuals with hearing loss are more expensive to take care of, when compared to a person of similar age with normal hearing (Foley, Frick, & Lin, 2014; Simpson, Simpson, & Dubno, 2016). We also know that untreated hearing loss can lead to poor adherence to treatment recommendations (Lawthers, Pransky, & Himmelstein, 2003) and preventable adverse events, like ending up in the emergency room by misunderstanding the doctors instructions and taking the wrong dosage of a critical medication (Bartlett, Blais, Tamblyn, Clermont, & MacGibbon, 2005).

The downstream consequences – the impact untreated hearing loss has on overall well-being, like physical health, cognition, social engagement and mental health – rounds out our triple threat concept. One of the most interesting threads of research to emerge over the past five years, much of it generated by Frank Lin and colleagues at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, suggests that hearing loss may actually accelerate conditions such as cognitive decline and poorer physical functioning. Evidence indicating untreated hearing loss has a direct impact on overall health is a real game changer, in my opinion. It creates urgency in the medical community and in the public at-large, suggesting that untreated hearing loss is not a benign condition, that passive acceptance of age-related hearing loss is not okay.

In the traditional audiology service delivery model, we had the luxury of passively waiting for patients to make a decision to get their hearing screened. Over time, if continued research does establish a linkage between age-related hearing and other serious medical conditions, audiologists must be more vigilant about getting involved sooner. After all, if age-related hearing loss indeed accelerates these other conditions, we have an ethical responsibility to be proactively involved with hearing screening. This idea is the cornerstone of interventional audiology.

The prevalence, co-morbidity and disabling effects of untreated, age-related hearing loss underscore the need for aggressive preventive programs that identify conditions such as hearing loss that threaten long-term health outcomes. Together, these three factors warrant the practice of interventional audiology. Furthermore, each of the three “triple threats” requires a unique set of skills to manage it effectively within an integrated care organization that emphasizes patient engagement.

13. I agree, it’s an important role for us, but to be more specific, how does it change the way I do things?

If we view age-related hearing loss as a triple threat with significant consequences, then we have to go beyond just simply telling patients “You have normal hearing for your age, let’s wait and re-test you in a year.” Think about your level of urgency if you identified a 5-year-old with a mild-to-moderate hearing loss. There are an abundance of services available, specifically because there is scientific evidence showing the effect that even a mild hearing loss has on speech and language development, as well as academic performance. Now, place that same mild-to-moderate loss on a 65-year-old. Until recently, most professionals didn’t have reason to intervene - it’s just a normal part of aging that the patient had to live with. But what if we knew that intervening sooner, or in different ways, would make a difference to the patient’s long-term health?

Hearing loss very often begins before the age of 60, but is usually diagnosed at a later stage. Although I don’t know of any research to support this claim, I think when patients wait several years before seeking treatment, until their hearing problems are obvious to everyone, they are more challenging to successfully treat—perhaps an issue related to brain plasticity. The delay between first noticing a mild problem with your hearing, and actually seeking help for it needs to be addressed through public awareness and education campaigns. This is yet another facet of interventional audiology. In 2012, the National Health Interview Survey data revealed that approximately 70% of women and 80% of men reported some difficulty with their hearing before the age of 60.

14. Is there more we can do besides getting people to have their hearing screened at a younger age and providing proper counseling?

The short answer to your question is yes, there is a lot more to this issue. Let’s discuss the challenges associated by accessibility and affordability, which is a major impetus for the PCAST’s recent guidelines. It is important to note that audiologists have been aware of the accessibility and affordability issues for several years. In 2010, Amy Donahue, Judy Dubno and Lucille Beck authored an NIH-sponsored paper, subsequently published in Ear and Hearing. The take-away from their working group was that “hearing loss is a public health issue and ranks among the leading public health concerns, with social and economic ramifications.” Their conclusion was that the current health care system in the U.S. is not meeting the needs of the vast majority of adults with hearing loss. Key opinion leaders in the profession recognized that we need to do something differently to better meet the needs of adults with hearing loss.

15. How much of a problem is accessibility and affordability?

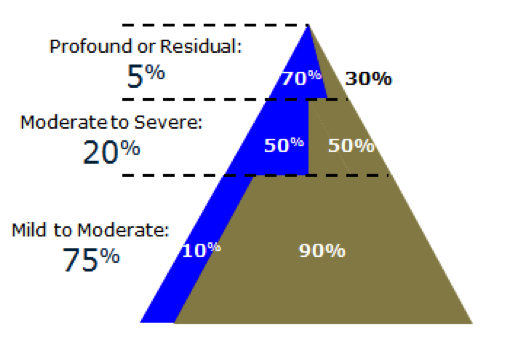

When you segment the adult hearing loss population in different ways you begin to identify gaps in the current patient delivery system, as well as opportunities to improve services. Figure 1 summarizes data from a compilation of studies. It shows hearing aid use as a function of degree of hearing loss. Notice that 5% of the American hearing-impaired population has a profound loss and 70% of this small group wears hearing aids or uses a cochlear implant. In the middle of Figure 1, you’ll see that 20% of the American hearing-impaired population has a moderate-to-severe loss and half of this group owns hearing aids. Finally, note the vast majority of the American hearing-impaired population has a mild to high frequency moderate loss, yet just 10% of them are hearing aid owners.

Figure 1. Hearing aid use as a function of degree of hearing loss. Based on Nash et al. (2013), Sonova (2011) and Wallhagen & Pettengill (2010).

There are a couple of important considerations that can be gleaned from these data and there are a couple of different ways you could interpret it. Here is my take: First, it tells us that the top 25% of the triangle, those with more severe and often more complex hearing losses, are content with the current service delivery model, predicated on fitting and fine-tuning hearing aids across several appointments. It’s not until the loss becomes greater, and perhaps more complex, that a patient even considers using hearing aids. This finding is in stark contrast to the bottom 75% of the triangle where just 10% are content to utilize the current service delivery model. By no stretch of the imagination does this mean audiologists do a bad job or that hearing aids are ineffective. On the contrary, the current MarkeTrak 9 survey indicates patient satisfaction and hearing aid technology have never been better (Abrams & Kihm, 2015). It does suggest, however, there are limitations to the current service delivery model for meeting the needs of individuals with mild to high frequency moderate losses.

What the segmentation data in Figure 2 may indicate is the current service delivery model is not valued by the bottom three-quarters of patients. The exceptionally low hearing aid usage rates by the large number of people with mild to high frequency moderate hearing loss is quite possibly because this group do not view themselves as having a problem that warrants a visit to a professional. Perhaps they view their hearing loss as an inconvenience or nuisance that’s “normal for their age.” By practicing audiology in the conventional way, waiting for these patients to age, have their hearing loss progressively worsen and eventually get late-stage diagnosed and treated by the audiologist is not a viable, long-term approach, if we want to be successful in the new era of consumer-driven healthcare.

16. How do you propose we meet the needs of those 75% at the bottom of the triangle?

Before I offer some ideas on how to better service this group, let me first say hearing difficulties are not always inextricably linked to the results of the audiogram. Tremblay et al. (2015) found that 15% of adults between the ages of 21 and 84 years had normal audiograms, but still had self-reported difficulties with communication. Further, another recent study (Taylor et al., 2016) looked at communication problems associated with working age adults with normal audiograms and found that between 20 to 40% of them had modest difficulties (or worse) with communication in ordinary listening situations like cafes, using their mobile phone or watching TV. This finding shouldn’t be too surprising when you consider that around 60% of adults between 54 to 66 years of age, many with normal hearing, report difficulty following conversations in noise (Hannula, Bloigu, Majamma, Sorri, & Mäki-Torkko, 2011). Given these study participants had essentially normal hearing sensitivity, we typically would not consider them candidates for hearing aids.

This is where hearables and PSAPs might offer some situational benefit and be part of a broader interventional audiology strategy. Imagine a 55-year-old man struggling with conversations in a restaurant. In the near future, he may be able to complete a smartphone-driven patient decision app that precisely rules out a medical hearing disorder and allows him to self-test his hearing. Once the app gives him the green light to self-treat, he has the ability to turn that same smartphone into a relatively sophisticated hearing aid with remote microphone capabilities that sends the amplified signal to a pair of custom fitted earbuds. For the typical Baby boomer who wants to more actively participate in his or her healthcare, this amplification approach might be very acceptable.

Now you might say, where does that leave the audiologist? There always will be the more complex cases. For those with milder losses, an audiologist may still be needed to navigate the myriad of technology options and ensure that both the physical and acoustic quality of the fitting is up to par, yet another component to interventional audiology.

17. So you are saying that hearables and PSAPs fit into an interventional approach?

If you recall one of the triple threats of hearing loss is that hearing loss impedes an individual’s ability to interact effectively with their physician, I think there are plenty of opportunities for audiology to intervene in the communication between a patient and their doctor. For the reasons I described earlier, good hearing is critical to following medical directives. In the past, ambitious audiologists offered pocket talkers; today it could be smartphone apps, or PSAPs. Catherine Palmer, Jenifer Fruit and Lori Zitell at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center provide this type of service and have presented about interventional audiology in their clinic (2015).

As I just mentioned in passing, an exciting development is the use of smartphone-based amplification applications (apps). These are apps you can download on your phone that essentially turn the smartphone into a hearing aid microphone and transmitter. There are several of them available for Android and iPhones. Rather than viewing them as a replacement for hearing aids, maybe we should think about them as starter devices that prepare people for hearing aid use. In one recent study (Amlani, Smaldino, Hayes, Taylor, & Gessling, 2016) involving 30 participants with hearing loss that had not purchased hearing aids, use of a smartphone-based amplifier reduced negative attitudes and psychosocial barriers towards hearing aids. The bottom line is, why not allow patients to use something that helps in specific listening situations, rather than throwing in the towel after they have rejected hearing aids or refused to wear them?

18. I see a lot of older patients. Does all this apply to them too?

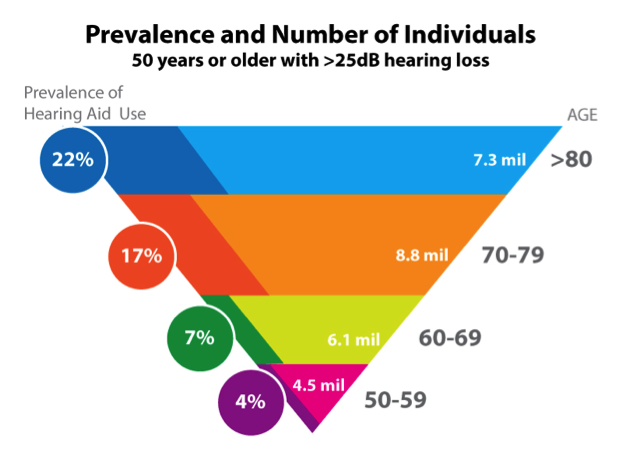

If what you mean by “older” are patients over the age of 80, then yes, even they can be helped through an interventional approach. This is another example of how segmenting data helps uncover an opportunity to address a gap in service. Shown in Figure 2 are data from Chien & Lin (2012) displaying hearing aid use as a function of age. Unsurprisingly, the younger the patient, the less likely it is they will own hearing aids – less hearing loss, passive acceptance, cost and stigma are obvious reasons for such low uptake among younger patients. What is interesting to me is the relatively large number of individuals over the age of 80 that don’t use hearing aids. Given that hearing loss is virtually a given with this age group, why is it that 78% of them don’t use them? A big reason is the high probability of cognitive decline, physical dexterity and general decline in health. Simply, many of these folks forget to wear their hearing aids or can’t physically insert them into or over their ears. Even low cost products worn in the ear cannot overcome these challenges. Audiologists can intervene by providing hearables, directed audio devices and assistive listening devices (ALDs) that allow older patients dealing with several co-morbidities to participate in common activities like watching television, talking on the phone or enjoying a group conversation.

Figure 2. Hearing aid use as a function of age. Data from Chien & Lin (2012).

19. How do I possibly begin to shift into an interventional audiology mode?

It starts by appreciating the limitations of the biomedical model that most of us currently use. The biomedical model centers on treating hearing loss as a correctable medical condition needing diagnosis and treatment. In order to do our job, patients with a hearing problem must find their way to the clinic, get tested and then fitted with hearing aids, if they are deemed appropriate. The biomedical model requires an accurate audiogram and a professionally conducted hearing aid selection and fitting protocol for patient success to be optimized. There is nothing inherently wrong with the biomedical model; it’s simply an incomplete way to view the role of audiology in the new era of consumer-driven healthcare.

Audiologists must recognize that there is a huge segment of the population, comprised of healthy agers, Baby boomers, and younger, working age people with normal hearing who struggle with communication in specific places that don’t value a biomedical approach, simply because they don’t think they have a problem. There are millions of Americans that fall into this category. Many of them have “normal hearing for their age” and desire a little help or assistance to enhance some aspect of daily communication. We need to find ways to intervene. We do this by offering alternative devices and by providing service in novel ways, maybe online via Skype, with a smartphone app or in a primary care setting. We cannot wait around hoping all patients will eventually want a pair of hearing aids and schedule an appointment in our clinics.

20. A lot to think about. Can you give me some practical tips to jump-start my venture into interventional audiology tactics?

I would start by abandoning the “hearing aid evaluation.” Instead, take a cue from audiologist Robert Sweetow and start conducting Functional Communication Assessments (Sweetow, 2007). This puts the focus on the patient, rather than the product, which is the foundation of consumer-driven healthcare. I would encourage everyone to read Robert’s 2007 Hearing Journal article on it. In my opinion, a functional communication assessment starts with assuming that patients with hearing difficulties are not automatically hearing aid candidates. The critical part is to focus on their self-reported difficulties. The use of some type of self-rating scale is extremely helpful in this area.

Another crucial aspect of patient-centered care is to utilize motivational interviewing skills. We don’t have time to get into the details, but the basis of motivational interviewing is allowing the patient to establish the agenda for the appointment and for the audiologist to facilitate dialogue with the patients around the whys and hows of taking action to communicate more effectively. Using this approach, the patients can tell the audiologist which devices or treatment approaches they want to learn more about, which is a great way to let the patient set the agenda for the functional communication assessment. The role of the audiologist is to inform the patient, based on test results and self-rating information, regarding the pros and cons of each solution. Thus, the role of the professional is still critical in the process.

References

Abrams, H.B & Kihm, J. (2015). An introduction to MarkeTrak IX: A new baseline for the hearing aid market. Hearing Review, 22, 6,16.

Amlani, A., Smaldino, J., Hayes, D., Taylor, B., & Gessling. E. (2016, April). Using smartphone applications to change attitudes about amplfication and hearing loss. Poster presentation at American Academy of Audiology conference, Phoenix, Arizona.

Bartlett, G., Blais, R., Tamblyn, R., Clermont, R.J., & MacGibbon, B. (2008). Impact of patient communication problems on the risk of preventable adverse events in acute care settings. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 178(2),1555-1582. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070690

Chien, W. & Lin, F.R. (2012). Prevalence of hearing aid use among older adults in the United States. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172, 292-203.

Donahue, A., Dubno, J.R., & Beck, L. (2010). Accessible and affordable hearing health care for adults with mild to moderate hearing loss. Ear & Hearing, 31,1, 2-6.

Hannula, S., Bloigu, R., Majamma, K., Sorri, M., & Mäki-Torkko E. (2011). Self-reported hearing problems among older adults: Prevalence and comparison to measured hearing impairment. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 22, 250-559.

Foley, D., Frick, K., & Lin, F. (2014) Association between hearing loss and healthcare expenditures in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 62(6), 1188-1189.

Lawthers, A.G., Pransky, G.S., & Himmelstein, J.H. (2003) Rethinking quality in the context of persons with disability. International Journal for Quality in Health Care,15(4), 287-299.

Nash, S.D., Cruickshanks, K.J., Huang, G-H., Klein, B.E.K., Klein, R., Nieto, F.J., & Tweed, T.S. (2013). Unmet hearing health care needs: The Beaver Dam Offspring Study. Am J Public Health,103(6), 1134–1139.

Palmer, C. (2015). Interventional audiology: when is it time to move out of the booth? AudiologyOnline, Recorded course 26151. Available at www.audiologyonline.com

Simpson, A., Simpson, K., & Dubno, J. (2016). Higher health care costs in middle-aged US adults with hearing loss. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg,103(6),1134-1139.

Sonova. (2011). Annual report. Retrieved from: https://www.sonova.com/en/investors/reporting/financial

Sweetow, R. (2007). Instead of a hearing aid evaluation, let's assess functional communication ability. Hearing Journal, 60(9), 26-31.

Taylor, B., Manchaiah, V., & Clutterbuck, S. (2016) Using the personal assessment of communication abilities (PACA) tool. Hearing Review, 23(3), 20.

Taylor, B., & Tysoe, B. (2013). Interventional audiology: Partnering with physicians to deliver integrative and preventive hearing care. Hearing Review, 20(12),16-22.

Taylor, B., & Tysoe, B. (2014). Forming strategic alliances with primary care medicine: interventional audiology in practice: How to leverage peer-reviewed health science to build a physician referral base. Hearing Review, 21(7), 22-27.

Tremblay, K.L., Pinto, A., Fischer, M.E., Klein, B.E., Klein, R., Levy, S.,...Cruickshanks, K.J. (2015). Self-reported hearing difficulties among adults with normal audiograms: The Beaver Dam offspring study. Ear & Hearing, 36(6), e290-9. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000195

Wallhagen, M.I., & Pettengill, E. (2008). Hearing impairment: Significant but underassessed in primary care settings. J Gerontol Nurs, 34, 36-42.

Citation

Taylor, B. (2016, May). 20Q: Interventional audiology - changing the way we deliver care. AudiologyOnline, Article 17080. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com