The US Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Noise Exposure Regulation became effective in 1971.1 So OSHA has been enforcing its regulations for 30 years. Since 1983, OSHA's regulation has included an amendment to require specific components related to hearing protection, audiometric testing, and training. This amendment has become known as the 'Hearing Conservation Amendment.'

How effective have these regulations been in preventing hearing loss in the workplace?

There is no brief, or abbreviated way to answer this question. Simply, the complexity of the problem and the complexity of the solution, beg a detailed analysis.

At a recent workshop hosted by the National Institute of Occupational Safety (NIOSH), I had the opportunity to pose this question to a number of 'seasoned' audiologists, noise control engineers, and manufacturing representatives.2 The consensus was that although OSHA's efforts have made a significant impact, we have fallen short of our expectations. What happened?

In 1971, when the original regulation became effective, events and policies made the practice of hearing conservation a fuzzy notion to plant management - and a low priority to others! In 1971, OSHA's intention was to 'remove the hazard' or 'remove the worker' when noise exposure reached a time-weighted average (TWA) of 90 dB. Importantly, hearing protection (accomplished through the use of hearing protection devices, HPDs) was to be used only as an interim measure until feasible engineering or administrative controls could be implemented.

However, during the 1970s, the word 'feasible' became a significant point of controversy in the new regulations and the burden of proof to show technical and economic feasibility (i.e., cost-effectiveness) rested squarely on OSHA's shoulders. This new burden, combined with diminishing resources, compelled OSHA to change strategies and enforcement policies. This was the beginning of the problem.

Efforts to Adopt a Better Standard

The ink had hardly dried on the new OSHA regulations when NIOSH published its first criteria document in 1972 for occupational noise exposure. The agency - which is an advisory arm of the federal government - immediately called upon OSHA to lower the permissible exposure level (PEL) from 90 dB to 85 dB TWA and to make other proactive changes to protect hearing in the workplace.

In 1974, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued its famous 'Levels' document which established criteria to protect the public health from the effects of noise - not just regarding speech communication and human comfort, but also on hearing.3 Based on this document, the EPA also called for OSHA to lower its PEL. Later that year, OSHA actually issued a proposed revision to make some of these changes. But the political climate was not right and the proposed changes 'fell on deaf ears.'

Through the years, OSHA was pressured to adopt more stringent changes and improve its regulation. Finally, in 1981, OSHA promulgated the Hearing Conservation Amendment (HCA), which effectively lowered the criterion level to 85 dB by requiring employers to implement a hearing conservation program (HCP) when exposures reached 85 dB TWA. OSHA called this the Action Level (AL).

Importantly, the HCA outlined five components of an effective HCP, and gave audiologists an important role as professional supervisors. Additionally, the HCA appeased industry because it allowed the elements of audiometric monitoring and hearing protection in lieu of potentially expensive engineering controls to prevent hearing loss in the workplace.

The HCA amendment was immediately pulled back by the Reagan administration for the Office of Management and Budget to scrutinize the amended standard with respect to its impact on industry. The review process took two years and during that time a number of companies actually thought the entire noise standard was pulled. It seemed that many companies were canceling their noise monitoring and mobile audiometric services in droves. In 1983, the final, stripped down, version of the HCA was released and hearing conservation was back on track - or so we thought.

How OSHA Lost its Influence on Hearing Conservation

Industry considered the 1983 standard a good move. They believed hearing loss could be prevented in the workplace just as effectively with audiometry and hearing protection as with engineering controls. Nevertheless, OSHA still preferred engineering and administrative controls. But by the mid-80s, policies and circumstances evolved that diminished the preference of these controls over hearing protection. Furthermore, these policies and events diminished the influence that OSHA had on companies to implement effective hearing conservation practices. Let's take a look at some of these policies.

Unfortunately, President Reagan terminated this office in the 1980s. Since ONAC was never eliminated through legislation, its rules and regulations are still on the books and the issue of noise has been relegated to EPA historians. In effect, 'the light is on, but nobody's home.' So currently (2001) the regulations are not being enforced, the surveillance of testing labs is slack, and federal efforts to update the NRR to include real-world factors has been virtually nonexistent (although the industry as a whole has made accomplishments).

For more information on CAOHC click here.

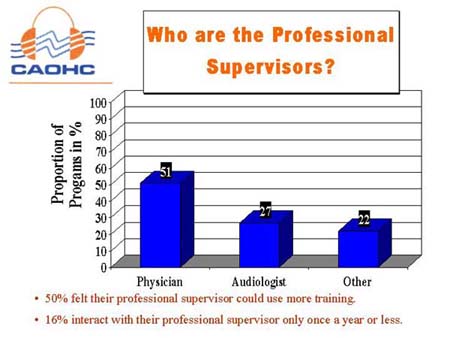

Two other curious findings resulted from this study: First, half of the 'supervised' technicians felt their supervisor would benefit from additional training. Second, 16% of the technicians conducting testing programs interacted with their supervisor (whoever it was) only once a year - or less! Based on this survey, CAOHC has begun sponsoring seminars on hearing conservation at the annual convention of the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. These seminars have been very well attended.

Nonetheless, when first introduced, OSHA blocked use of these devices and indicated their use would be subject to a de minimus (hand slap) violation. Given the 'novelty' of inserts, OSHA's early position was understandable - ANSI had not yet standardized these devices. However, ANSI did eventually standardize inserts. When this happened, and later when direct calibration became available from calibration service providers, insert earphone use grew rapidly in popularity. Currently, the majority of audiologists use such devices.

Despite the superiority of these devices, OSHA has yet to react favorably to their use and continue to hinder their full implementation in industry requiring a cumbersome and time-consuming 'dual test' with both inserts and headphones when converting a program to insert use. This is unfortunate since the use of inserts would enhance the audiometric testing component of a hearing conservation program - not degrade it.

So - What is the Present Situation?

As mentioned above, OSHA issued an amendment in 1983 that required a HCP when noise exposures reached 85 dB TWA - known as the 'action level.' Industry has always preferred HCPs, presumably because of their lower cost relative to engineering or administrative controls.

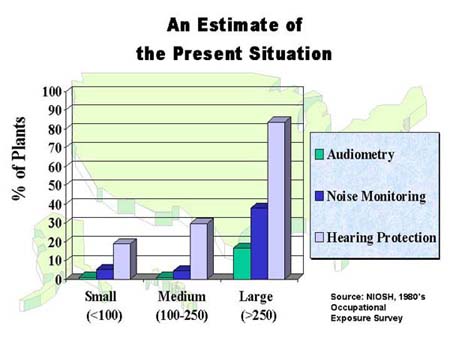

The most salient feature of this amendment was the mandate to include five components in the HCP: 1) noise monitoring, 2) hearing protection, 3) annual audiometry, 4) training, and 5) records. But has industry been including all five components in their programs? It does not appear so according to a late 1980s estimate based on a U.S. national occupational exposure survey of about 4500 companies.6 The results of this study, as seen here, show that large companies were the best at providing hearing protection. In contrast, noise monitoring occurred in substantially fewer plants and audiometry in even fewer plants. The trend was the same for medium and small plants.

It's easy to understand why the use of hearing protection is the most common aspect of a HCP. After all, the earplug is the icon of hearing conservation. Unfortunately, as illustrated above, not much consideration is given to other important components. Noise assessment, for example, is necessary to identify those who must be included in an HCP, to evaluate the need for engineering/administrative controls, to prescribe adequate hearing protection, and to assess the work-relatedness of hearing loss. Audiometry is necessary to flag employees for follow-up action and to assess the overall effectiveness of a program. Yet, as seen in this graph monitoring hearing was almost nonexistent. And although employee training, another HCP component, was not an item in the NIOSH study, it is probably more neglected than the other HCP components. Is this trend the same today? I'd like to believe it is better - and it probably is to a very small degree. However, experience indicates it's probably not significantly better.

Another study that points to the lack of effective HCPs can be seen in the 1997 Annual Report on Occupational Hearing Loss which was conducted in Michigan.7 Two important findings from this report were:

1- The most significant number of people seeing an audiologist due to possible noise-induced hearing loss was in the 40-45 year old range.

2- 43% of the companies employing baby boomers had no hearing conservation program!.

Yet the 40-45 year old group would have entered the workforce within the last 30 years - the period during which OSHA was in force. So even though the NIOSH study was done over a decade ago, it is fair to say we still have a problem in the US in hearing conservation

Which Companies Need our Help the Most?

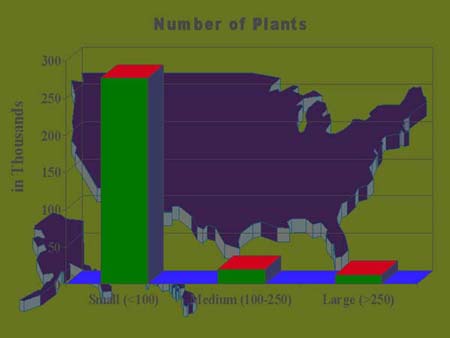

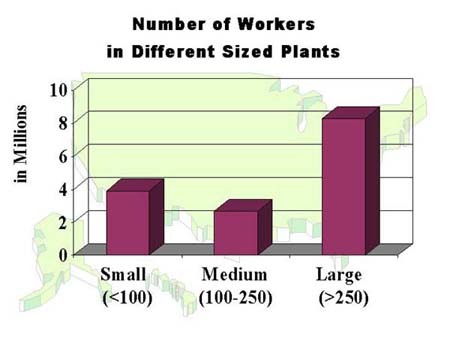

It's evident (from the graph above) that small and medium sized manufacturing plants aren't doing a very good job at hearing conservation. Importantly, small plants - those defined as less than 100 people - comprise the vast majority of manufacturing companies in the US. In fact, there are over 10 times as many small plants as there are medium and large plants combined!

OK. But does that reflect how many actual workers might be affected? To answer this question, take a look at the next figure. This graph, adopted from earlier OSHA statistics, shows that small and medium plants employ nearly half of the total manufacturing workforce.8

Why have small and medium sized plants been remiss? In small companies, the person in charge of safety and health is usually a foreman, supervisor, plant manager, or even the plant owner himself. These people wear many different hats and hearing conservation is not a high priority for them. The situation is a little better in medium-sized companies because there is usually a key person responsible for safety and health. Unfortunately, that person often lacks comprehensive education and training regarding hearing conservation.

As expected, the situation is best in large companies simply because these corporations employ professionals who are normally aware of the need for effective HCPs. These people typically include occupational health nurses, industrial hygienists, and safety engineers. In the largest of companies, occupational physicians and audiologists are even employed such as 3M and United Airlines.

From the information above, it's evident that additional hearing conservation efforts should be focused on small and medium sized companies - not the large companies. In general, the large companies are already doing hearing conservation. If they are not conducting the programs themselves, then they outsource the services to companies that specialize in industrial audiology. Certainly, 'outsourcing' has its advantages, but from the small to medium sized company's perspective, it can be expensive.

Remember too, that many plants have 2 or 3 shifts and some even have a 'swing' shift if they operate on a 24/7 basis. So scheduling a mobile van can be problematic. In most cases, two shifts are combined so that the tail end of one shift and the beginning of the next shift are tested back-to-back. This, however, is contrary to good practice (per the new NIOSH guidelines) where baseline and repeat tests should be completed at the beginning of the shift and annual tests should be completed at the end of the shift. Doing so enhances the early identification of those susceptible to noise-induced hearing loss.

Hearing Conservation in the USA in 2001

Our entire discussion above suggests that a lot more needs to be done to promote hearing conservation in the US. The National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), National Institutes of Health (NIH), in collaboration with the National Institute on Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), and National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) is preparing a national campaign to promote the idea that each worker and employer should be aware of the importance and value of hearing. This campaign recognizes that hearing health is not currently a national priority, while the average citizen is exposed to more noise risks than ever before. Yet, few people are motivated to take the necessary self-protective actions to protect their hearing.

These national organizations believe that once a person places a high value on their hearing, they'll seek out the appropriate methods of self-protective behavior whether on or off the job, by means of noise control, avoidance, or hearing protection. The objective of the campaign is to increase recognition that our ears need the support of our healthcare system in the same way that visual, dental, cardiovascular, and other health issues are recognized and supported.

Communicating with Small and Medium Sized Companies

Attempting to help companies improve their hearing conservation efforts is not simply a matter of walking in and declaring, 'OSHA says you have to do it.' Savvy companies realize that OSHA is not the threat it used to be. In a relative sense, the fines are not that big and some companies choose to defer implementing a program until OSHA requires them to do so. Besides, simple compliance with the OSHA regulations does not ensure full protection from noise-induced hearing loss. In fact, many in the field of hearing conservation have criticized the OSHA regulations as 'hearing loss documentation' not 'hearing loss prevention.'.

Instead, be prepared to discuss the benefits of noise reduction and hearing conservation. The obvious benefit is that a hearing conservation program will protect hearing in the workplace and foster a safer work environment. But as highlighted in a recent editorial by Stephen Roth, President of the Institute of Noise Control Engineering, additional benefits include:

Regardless of the sources of the hearing loss, it is likely that the employer will bear the responsibility for that loss. Therefore, you need to stress to companies in your area that hearing conservation is simply good business practice. As was stated over a decade ago by Berger and Royster, 'In large part, what is needed is not the development of new solutions, but rather the broad dissemination of existing techniques plus the education and motivation of management and labor alike to speed the implementation of effective programs.'9

How to Increase your Knowledge about Hearing Conservation.

First, get on line to OSHA and read over its Noise Exposure Regulation Then get on line with NIOSH and review its new 'Criteria for a Recommended Standard: Occupational Noise Exposure.' You may also want to look over the NIOSH publication, Preventing Occupational Hearing Loss. Consider joining the National Hearing Conservation Association to get information on occupational audiology and position statements on issues such as training audiometric technicians and revising baseline audiograms.

You can also read a new book that just came out called 'The Noise Manual' published by the American Industrial Hygiene Association.10 edited by Elliot Berger, Larry and Julia Royster, Dennis Driscoll, and Martha Layne. This book is actually the fifth edition of a long history of noise and hearing conservation books published by the AIHA. It is the most comprehensive and practically written book of this topic and written by some of the most respected names in hearing conservation.

Perhaps the best way to enhance your knowledge and training in hearing conservation is to enroll in an Au.D. distance-learning program and take their hearing conservation course. I can't speak for all the programs, but the one I teach at the Pennsylvania College of Optometry is a practical, 'how to' course. Many courses are geared toward the academic aspects of the effects of noise, noise-induced hearing loss, and damage risk criteria. In the PCO course, we get into all aspects of supervising a program and reviewing data using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet template.

CONCLUSION

The debate will continue on whether the existing noise regulation is sufficient to protect hearing in the workplace. Most everyone would agree, however, that we could make great gains my simply adopting the standard in whole just as it is written - not part of it, but all of it.

Most companies extol the virtues of a safe and healthy workplace. But can such a workplace exist when excessive noise levels create unsafe environments and result in worker hearing loss? There is now doubt that in the past 30 years, OSHA has made significant strides in preventing hearing loss. But we cannot depend on OSHA alone to lead us down this road. Instead, audiologists need to appeal to the consciousness of management to 'do the right thing' and protect the hearing of their employees.

REFERENCES:

1. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Noise Exposure Regulation, 29 CFR 1910.95.

2. National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, Control of Workplace Hazards for the 21st Century: Setting the Research Agenda, Chicago, IL, March 10-12, 1998.

3. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 'Information on Levels of Environmental Noise Requisite to Protect Public Health and Welfare with and Adequate Margin of Safety,' Report no. 550/9-74, Washington, DC, 1974.

4. National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, 'Criteria for a Recommended Standard: Occupational Noise Exposure,' Report 98-126, Cincinnati, OH, 1998.

5. Council for Accreditation in Occupational Hearing Conservation, 'Who is Your Professional Supervisor?' Update, Vol. 8(2), 1997.

6. Franks, J., and Burks, A., 'Engineering Noise Controls and Personal Protective Equipment,' in Control of Workplace Hazards for the 21st Century - Setting the Research Agenda, NIOSH, Cincinnati, OH, 1998.

7. Michigan Industrial Commission, Annual Report on Occupational Noise-Induced Hearing Loss, 1997.

8. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Final Regulatory Analysis of the Hearing Conservation Amendment, Washington, DC, 1981.

9. Berger, E., and Royster, J., 'The Development of a National Noise Strategy,' Sound and Vibration, Vol. 21(1), 1987.

10. American Industrial Hygiene Association, The Noise Manual, edited by Berger et al, Fairfax, VA, 2000.