From the Desk of Gus Mueller

From the Desk of Gus Mueller

I recently stumbled across a web page of an audiology practice that had the headline “Tinnitus Experts.” How does one become a tinnitus expert I wondered—I certainly know that I am not!

I think that most of us would agree that audiologists are the most logical, and best suited professionals to have the identification, treatment and management of tinnitus in our scope of practice. That alone, however, doesn’t make us experts. It was 6-7 years ago when I read an article titled: Clinical Protocol to Promote Standardization of Basic Tinnitus Services by Audiologists. And then a few months later, I saw another article simply titled: Audiologists and Tinnitus. The senior author of both articles was audiologist James Henry (more on him later).

These articles, and others like them, make the point that regarding tinnitus, there seems to be little standardization of services, and determination of exactly what makes a person a “tinnitus expert.” Patients, therefore, could receive services that may appear legitimate, but are not based on research evidence.

How are our professional organizations and training programs handling this? Dr. Henry, our 20Q author this month has this to say: “AuD training programs are not held accountable to ensure that students acquire knowledge about common methods of tinnitus assessment and treatment that could be tested with the national exam (Praxis Examination in Audiology). The AuD degree, therefore, does not ensure an adequate knowledge base to provide tinnitus services.”

James A. Henry, PhD, is an audiologist with a doctorate in behavioral neuroscience, known for his decades of extensive research, much in the area of tinnitus. He has authored over 260 publications, and 10 books. In this month’s 20Q, he’ll offer some guidance on how we can move forward in the treatment and management of tinnitus.

Dr. Henry, now in “partial retirement,” conducts training workshops, serves as an educational consultant, and is an editor-at-large for the American Tinnitus Association’s journal Tinnitus Today. In the past few years, he has published four books under his corporation Ears Gone Wrong, LLC.

His most recent book, Tinnitus Stepped-Care: A Standardized Framework for Clinical Practice, relates to the need for standardization. In this excellent 20Q article, Jim lays out, in a step-by-step manner, how you can apply this standardized framework in your practice and clinical services. And who knows, you may become an expert!

Gus Mueller, PhD

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller CEU articles at www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: Adopting Tinnitus Stepped-Care as Standard Practice

Learning Outcomes

After reading this article, professionals will be able to:

- Define tinnitus and related terminology, and explain the distinctions between transient ear noise, temporary ear noise, occasional ear noise, intermittent tinnitus, and constant tinnitus.

- Describe the six steps of the Tinnitus Stepped-Care framework and their clinical implications.

- Explain why it is important to differentiate between various types of ear noise and tinnitus for appropriate clinical intervention.

1. Tinnitus seems to be a hot topic these days. However, relevant terminology and definitions are inconsistent and confusing. For starters, is there an agreed-upon definition of “tinnitus”?

Sure, that’s easy—tinnitus is “ringing in the ears.”

But what if it doesn’t sound like “ringing”?

Okay, then—tinnitus is “sound in the ears or head that does not have an external source.”

If I hear a sudden tone in one ear that lasts about 30 seconds, is that tinnitus?

Actually, no. That’s transient ear noise. The sound has to last at least 5 minutes to be considered tinnitus.

Like when I went to a rock concert and my ears rang all night long?

That’s still not what we’re talking about. You experienced temporary ear noise following the rock concert. The sound in your ears has to last at least 5 minutes and occur on a regular basis.

I’ve had ear noise that lasted more than 5 minutes a couple of times in the last year. Was that tinnitus?

Again, no. That was occasional ear noise. The noise needs to last at least 5 minutes and occur at least weekly to be considered tinnitus.

Oh, then I guess I don’t have tinnitus.

Correct. You’ve had various forms of ear/head noise, but none of these would be considered tinnitus.

What’s the difference, and why does it matter? Aren’t these all just variations of tinnitus?

You mentioned that terminology and definitions relevant to tinnitus are inconsistent and confusing. Our back-and-forth dialogue just demonstrated the truth of that statement. I believe it’s important to distinguish ear noise from tinnitus.

2. Why is it important to distinguish ear noise from tinnitus?

It seems almost every article about tinnitus starts with a definition of tinnitus, which is usually some version of the following: “Tinnitus is generally defined as the perception of sound in the absence of a corresponding external source” (Fioretti, 2025) or “Tinnitus is a prevalent condition characterized by the perception of sound in the absence of external stimuli” (Miao et al., 2025). These types of definitions would mean any sound in the ears or head qualifies as tinnitus. Here’s why it matters to distinguish ear noise from tinnitus: Some types of ear/head noise would be considered a medical condition, while other types would not.

3. What would make ear/head noise a medical condition?

Transient ear noise is a phenomenon that is experienced by almost everyone. Transient ear noise is not a medical condition.

Years ago, different authors attempted to differentiate tinnitus from transient ear noise by specifying that ear or head noise must exceed 5 minutes to qualify as tinnitus (Coles, 1984; Davis, 1995; Hazell, 1995). Another definition to make this distinction was head noise that lasts at least 5 minutes and occurs at least twice weekly (Dauman & Tyler, 1992).

Tinnitus is usually constant, meaning it can be heard in any quiet environment. Constant tinnitus is a medical condition because of the high probability these people have hearing loss and thus they require an audiologic evaluation (Kimball et al., 2018). Often, they don’t realize they have hearing loss, and they blame their tinnitus for any hearing difficulties they experience (Ratnayake et al., 2009). Also, many people with tinnitus have a normal audiogram but impaired cochlear function (Xiong et al., 2019).

4. If tinnitus isn’t constant, it’s not a medical condition?

A reasonable definition of tinnitus is sound in the ears and/or head that lasts at least 5 minutes and occurs at least weekly (Henry, 2024a). For most people, that definition is irrelevant—their tinnitus is constant. If a person’s tinnitus is not constant, then the definition is needed to determine if they really have tinnitus, or if they have only experienced some type of ear noise, which would be any sound in the ears and/or head that does not meet the definition.

5. What types of sound in the ears and/or head would not meet the definition of tinnitus?

The various types of ear noise are transient, temporary, and occasional (Henry, 2024a). Some people have ear noise and they think they have tinnitus. The Tinnitus Screener is a one-page algorithmic questionnaire that can be used if there’s any question whether a person’s reported tinnitus might be ear noise (Henry et al., 2016; Thielman et al., 2023).

Transient ear noise is the perception in one ear of a sudden tone, often with ear fullness and hearing loss (Henry et al., 2010; Levine & Lerner, 2021). Within 30 seconds or up to a few minutes, the symptoms subside. Transient ear noise is a “nearly universal sensation” (Dobie, 2004) and no cause for concern. Although it has been referred to as “brief spontaneous tinnitus,” it is not consistent with the definition of tinnitus.

Anything that can cause temporary threshold shift (TTS) can also cause temporary ear noise, which can last some number of days (Henry, 2024a; Quaranta et al., 1998; Simpson, 1999). Temporary ear noise is typically referred to as “temporary tinnitus” (Chermak & Dengerink, 1987; Dobie, 2004; Norman et al., 2012). Using the definition of tinnitus, temporary ear noise does not qualify as tinnitus.

Some people report ear noise that lasts 5 minutes or more but occurs less than weekly (Henry, 2024a). Such ear noise is inconsistent and unpredictable and does not fit the definition of tinnitus. Ear noise lasting at least 5 minutes but occurring irregularly (less than weekly) is categorized as occasional ear noise.

6. Wouldn’t occasional ear noise be considered intermittent tinnitus?

Using the definition of tinnitus as sound in the ears and/or head that lasts at least 5 minutes and occurs at least weekly, tinnitus can be constant or intermittent. People have constant tinnitus if they can always hear their ear/head noise in a quiet environment (Henry, 2016). If they can’t, their tinnitus is intermittent if the ear noise lasts at least 5 minutes and occurs at least weekly.

Intermittent tinnitus means the ear/head noise switches between present and absent on a regular basis (Henry, 2016). It’s a concern, however, that the perceived “intermittency” may be explainable because the person switches between being aware and unaware of a sound that is always there.

Awareness of tinnitus can be affected by the acoustic environment and by mental distraction. The acoustic environment is always changing. Many people have tinnitus that is easily masked (Meikle & Taylor-Walsh, 1984), which could make them think the tinnitus is absent when it is just being masked. Similarly, distraction can make a person unaware of the presence of tinnitus (Henry, 2016). Any report of intermittent tinnitus should be interpreted with these concerns in mind.

7. Why distinguish between occasional ear noise and intermittent tinnitus?

This distinction is important to determine if clinical services are needed. It may seem arbitrary, but it’s important to have a cutoff point when ear/head noise would be considered a medical condition. If it’s sound in the ears and/or head that lasts at least 5 minutes and occurs at least every week, then it is a medical condition requiring medical services—at least a hearing evaluation. Otherwise, it’s not a medical condition. This is one of those issues that requires professional consensus, but don’t hold your breath!

Because occasional ear noise may be a precursor to intermittent or constant tinnitus, counseling in hearing conservation is essential. Such counseling is also essential if a person experiences temporary ear noise following noise exposure. If there is uncertainty whether a person has tinnitus or not, then audiology services should be provided.

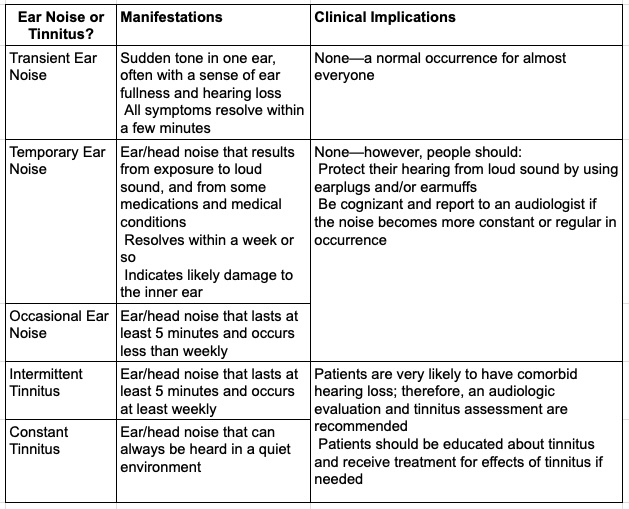

Table 1 summarizes the different forms of ear noise and tinnitus.

Table 1. Distinguishing ear noise (a non-medical condition) from tinnitus (a medical condition).

8. Okay, that helps. I’ve heard people talk about management, intervention, and treatment for tinnitus. Are these really three different things?

In some ways, yes. Consider a person with a hypothetical medical condition. If the condition is managed, then efforts are made to improve or remediate the condition. The efforts can involve professional services (clinical management) and/or the person’s own efforts (self-management).

Clinical management may include recommendations for self-management, which is generally what’s done for a chronic condition such as pain or tinnitus. If the condition is not managed, then it runs its course. Unmanaged pain that runs its course, for example, would either resolve on its own (spontaneous remission), remain unchanged, or become worse. That would be true also for unmanaged tinnitus.

Management is the overall term that pertains to anything that is done in an effort to address medical symptoms. Clinical management includes the other terms we’re discussing—intervention and treatment.

Clinical procedures to reduce effects of tinnitus are sometimes referred to as intervention rather than treatment (Beukes et al., 2020). According to merriam-webster.com, the definition for intervention is “the act of interfering with the outcome or course especially of a condition or process (as to prevent harm or improve functioning).” Their definition for treatment is “management and care to prevent, cure, ameliorate, or slow progression of a medical condition.” It may be splitting hairs, but the word treatment seems preferable—meaning management and care to ameliorate or slow progression of bothersome tinnitus. Otherwise, the words can be used interchangeably.

9. One more point of clarification. Aren’t there two types of tinnitus, subjective and objective?

Oh boy, this is always a tough one because of preconceived notions. To answer the question, I defer to the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery Foundation (AAO-HNSF) in their Clinical Practice Guideline: Tinnitus (Tunkel et al., 2014). They noted that the classifications of subjective tinnitus and objective tinnitus are inconsistent and incomplete, hence not recommended. They describe primary tinnitus as “idiopathic and may or may not be associated with sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL)” (p. S2). They describe secondary tinnitus as being “associated with a specific underlying cause (other than SNHL) or an identifiable organic condition” (p. S3). The terminology and definitions recommended by the AAO-HNSF are logical and all-inclusive for distinguishing between the two most basic categories of tinnitus.

Subtypes of primary tinnitus include somatosensory tinnitus (aka somatic tinnitus or somatically modulated tinnitus), which refers to the ability to modulate the pitch or loudness of tinnitus using some kind of physical contact or movement, usually involving areas of the head or neck; and reactive tinnitus, which becomes louder and stays louder for hours or days when exposed to certain everyday sounds. Arguably, another subtype of primary tinnitus is musical tinnitus (aka musical hallucinations), which is the uncontrollable perception of phantom music (not to be confused with earworms) (Perez et al., 2017).

Objective tinnitus has typically been defined as sound that can be heard by both the affected individual and an examiner. By definition, therefore, objective tinnitus is characterized by sound waves generated in the head or neck. Objective tinnitus has also been referred to as somatosound(s). It should be noted that a somatosound is a subtype of secondary tinnitus.

Importantly, secondary tinnitus can have causes that don’t generate sound waves and thus would not be considered somatosounds (Tunkel et al., 2014). Those causes can include a range of auditory and non-auditory system disorders. Auditory system disorders that can underly secondary tinnitus include Ménière’s disease and auditory nerve pathology such as vestibular schwannoma. Non-auditory system disorders that could underly secondary tinnitus include intracranial hypertension, tumors, and heart problems.

10. It’s all kind of confusing, but your terminology and definitions make sense. What about standards for providing tinnitus-related clinical services—are there any?

Unfortunately, we do not have standards. Any audiologist can claim to be a tinnitus expert, provide any type of clinical services, and charge a fee for those services. There is no formal system in place to ensure that an audiologist is competent in providing tinnitus clinical management. This of course means that people can’t know for sure if a particular audiologist is qualified to address their bothersome tinnitus.

On the other hand, as already mentioned, people with tinnitus are likely to also have hearing loss. A visit with any audiologist is therefore appropriate to evaluate their hearing function. Further, all audiologists know about tinnitus and can answer many questions from patients. Audiologists know when to refer patients to ENT, mental health, or emergency care. They can provide hearing aids if necessary, which can be helpful for mitigating effects of tinnitus. Most hearing aids also have built-in sound generators and audio streaming capability, which makes them an excellent tool for providing innumerable forms of sound therapy.

11. If audiologists can do so much, is it a problem if they aren’t certified as competent in tinnitus management?

Good question! It’s really only a problem if patients require special services to treat their bothersome tinnitus. It’s commonly reported that about 80% of people who have chronic tinnitus are not particularly bothered by it (Henry et al., 2020). The remaining 20% are significantly impacted by their tinnitus and they may need treatment. If they do, relatively few audiologists are qualified to provide treatment (Henry, 2026; Henry et al., 2021; Husain et al., 2018). That’s the problem.

12. Why are so few audiologists qualified to provide treatment for tinnitus?

I address this question in my book,Tinnitus Stepped-Care: A Standardized Framework for Clinical Practice (Henry, 2026). In a nutshell, AuD training programs are not held accountable to ensure that students acquire knowledge about common methods of tinnitus assessment and treatment that could be tested with the national exam (Praxis Examination in Audiology). The AuD degree, therefore, does not ensure an adequate knowledge base to provide tinnitus services. If the ASHA standards for certification were written to cover essential methods of tinnitus management, then the academic programs, national exam, and CCC-A would also address tinnitus.

13. How can audiologists become competent in providing treatment for tinnitus?

Of the 80 or so AuD graduate programs in this country, some offer excellent training in tinnitus management, and these audiologists are well-prepared to provide tinnitus services (Henry et al., 2021). Audiologists who have not had substantial training in tinnitus management techniques have several options available.

Ideally, training would involve completing a comprehensive instructional course followed by a supervised clinical practicum. This ideal level of training simply is not available to the great majority of audiologists. The alternative is for audiologists to become self-taught in tinnitus clinical management, and learn as much as they can about the different established methods, including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) (Beukes et al., 2021), Tinnitus Retraining Therapy (TRT) (Henry, 2024b; Jastreboff & Hazell, 2004), Tinnitus Activities Treatment (TAT) (Perreau et al., 2022), and Progressive Tinnitus Management (PTM) (Henry, 2025b). With that information, audiologists are in a position to provide basic tinnitus counseling, including suggestions for how patients can perform sound therapy.

Books and book chapters to learn about the different methods of tinnitus treatment are available for CBT, TRT, TAT, and PTM. These resources can be used by audiologists for self-instruction. The information gained from these resources would be added to audiologists’ existing skills to expand their clinical practice to include tinnitus services. Audiologists can become capable of providing patients with all the counseling needed, and to know when to refer patients to receive CBT or other counseling from an appropriate psychological health provider.

The Tinnitus Stepped-Care book also covers the information I consider essential for audiologists to provide tinnitus clinical services (Henry, 2026). This book is unique in that it focuses on principles of tinnitus care rather than specific procedures. Within each of the six progressive steps of care, the audiologist can perform a variety of different procedures based on their training and expertise, as long as the key principles are addressed. The essential steps of care to serve the great majority of patients with tinnitus are Step 2 Audiology Services, Step 3 Tinnitus Education, and Step 4 Tinnitus Counseling.

14. Can you elaborate on those three steps?

Step 2 Audiology Services involves little more than what is normally done to evaluate a person’s hearing. In addition to the routine medical history and hearing evaluation, an assessment is made to determine the degree to which tinnitus affects the person’s life, which requires ensuring the person is not blaming the tinnitus for any hearing difficulties (Ratnayake et al., 2009). Patients should also be screened for a sound hypersensitivity disorder (hyperacusis, misophonia, etc.) (Henry, 2025a). Audiologists then decide if referral to another discipline is needed.

The tinnitus assessment and screening for sound hypersensitivity can both be accomplished in less than 10 minutes using the Tinnitus and Hearing Survey (THS) (Henry et al., 2015). Although the intent of Tinnitus Stepped-Care is to suggest principles of care rather than procedures, the THS is specifically recommended because it is the only instrument documented both to determine if tinnitus is bothersome (and not blamed for hearing problems) and to screen for a sound hypersensitivity disorder. Patients who screen positive for sound hypersensitivity should be scheduled for a separate appointment to fully evaluate their sound sensitivity complaints (Henry, 2025a).

The Step 2 Audiology Services assessment determines if any further services are needed. If the patient receives hearing aids, then hearing aids are dispensed and the patient is evaluated 1-2 months later to determine if all needs are met.

If tinnitus services are needed beyond Step 2, then Step 3 Tinnitus Education provides the patient with the information essential to make an informed decision about receiving tinnitus-specific treatment. The education should be substantial, typically requiring about an hour of instruction. The educational content should include a description of the different aspects of tinnitus, how and why it can become problematic, and realistic methods to restore the person’s quality of life in spite of the ongoing presence of tinnitus. Live instruction (in-person or videoconference) optimizes patient engagement and the opportunity to have questions answered.

With the information gained from the Step 3 Tinnitus Education, the patient is empowered to decide if treatment is desired. If so, then Step 4 Tinnitus Counseling is offered, which usually involves some combination of behavioral counseling and sound therapy. Patients may receive CBT from a psychological health provider. Audiologists can perform some components of CBT if they have received proper training and supervision (Henry et al., 2022). CBT usually includes a recommendation to utilize some form of sound therapy. Evidence-based methods that would usually be performed by audiologists at Step 4 include TRT, TAT, and PTM.

15. Can audiologists develop their own tinnitus counseling protocol?

Indeed, audiologists can develop their own tinnitus counseling protocol. If they do, then I would suggest the following points should be covered:

- Identify the person’s unique symptoms and complaints

- Focus counseling to address the primary concerns

- Identify lifestyle behaviors that may contribute to the symptoms

- Review any tinnitus educational information previously provided

- Briefly describe and differentiate CBT, TRT, TAT, and PTM

- Explain third-wave CBT and how it differs from traditional (second-wave) CBT

- Describe how short-term relief from tinnitus can be achieved

- Explain habituation as the ultimate goal of all types of tinnitus treatment

- Explain how sound therapy can be used for distraction, relief, and habituation

- Explain the use of smartphone apps for sound therapy and other treatments

- Explain why hearing aids can be helpful for treating tinnitus

This is a lot of material to cover and would likely require multiple appointments. The amount of counseling, and what exactly is covered, should be dictated by the patient’s specific need. Many factors determine how much counseling is needed for a patient, so the appointment schedule should be flexible to address individual needs.

16. How can audiologists become proficient in these three steps?

Motivated audiologists can learn to provide these services utilizing existing resources. It’s not ideal to learn everything on their own, but it is certainly doable. Providing the Steps 2, 3, and 4 described here will meet the needs of most patients with tinnitus.

Step 2 Audiology Services is fairly easily accomplished. Step 3 Tinnitus Education requires putting together an instructional presentation with PowerPoint and delivering it live to patients, either in person or via videoconference. For Step 4 Tinnitus Counseling, audiologists can learn to perform TRT, TAT, or PTM. They can put together their own counseling protocol, using the key points listed in response to question #15. They can even learn to perform certain components of CBT (Beukes et al., 2021; Henry et al., 2022).

17. What are the other steps in Tinnitus Stepped-Care?

As an overview, there are six steps that would be followed by a clinic adopting the Tinnitus Stepped-Care framework (Henry, 2026):

- Step 1 – Triage: Inform other hospitals and clinics in their geographic area about tinnitus and how to properly refer patients who complain of tinnitus.

- Step 2 – Audiology Services: Conduct the initial assessment of patients using a minimum of specific measures that are consistent across clinics.

- Step 3 – Tinnitus Education: Advance patients with bothersome tinnitus to learn about tinnitus, how and why it can become bothersome, and what realistically can be done about it.

- Step 4 – Tinnitus Counseling: Make available an established, research-based method of treatment for tinnitus.

- Step 5 – Comprehensive Assessment: Conduct a comprehensive assessment for patients who require further care to determine why services thus far have been inadequate.

- Step 6 – Expanded Treatment: Provide further treatment or refer patients to another tinnitus specialist to address any needs identified in Step 5.

We’ve already discussed Steps 2, 3, and 4, so now I will elaborate on Steps 1, 5, and 6.

Step 1 Triage addresses the concern that patients report the presence of tinnitus to personnel in various healthcare settings, including primary care clinics, specialty clinics, rehabilitation facilities, care homes, etc. People who work in these settings typically don’t know what to say to patients to inform them how to receive proper clinical services for their tinnitus. Step 1 Triage provides guidelines to triage patients appropriately based on their symptoms. The Tinnitus Referral Guide is available for this purpose (Henry, 2025b).

The Tinnitus Referral Guide (or a comparable guide) is distributed to these various healthcare settings. The guide should be short and simple so that healthcare workers can quickly determine where to triage a patient for tinnitus clinical services. If there’s any question, patients complaining of tinnitus should be triaged to an audiologist for a hearing assessment and to determine if a referral is needed to an ear-specialist physician, mental health clinician, or emergency care.

If Steps 2, 3, and 4 were conducted with good fidelity, then Steps 5 and 6 would not be needed for most patients. Those few patients who do not have their needs met through Step 4 can be offered the more intensive services in Steps 5 and 6.

At Step 5 Comprehensive Assessment, patients are evaluated by both an audiologist and a psychologist. The assessment is comprehensive, thus about an hour is needed with each clinician. The clinicians first review results of questionnaires that were completed during previous steps. The audiologist completes an in-depth interview (such as the Tinnitus Interview) and the psychologist administers a battery of questionnaires that assess for depression, anxiety, insomnia, and other psychological conditions that might underlie the patient’s lack of success (Henry, 2026).

Following the assessment, the audiologist and psychologist discuss the results and consult with the patient to make a decision about any need for further treatment. If treatment is desired, then a plan for individualized and extended care (Step 6) is developed.

Step 6 Expanded Treatment can either extend the therapy provided in Step 4, or provide a completely different therapy. Treatments can include commercial devices (e.g., bimodal stimulation), complementary and alternative methods (such as acupuncture), and methods considered “experimental” such as various forms of electrical stimulation and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS).

It is essential to inform patients of risk versus benefit for any treatment being considered. Nothing is ruled out unless the risks are too great or if the treatment is cost-prohibitive. Patients may believe a certain therapy will help in spite of the lack of evidence. The clinician has the critical role of informing the patient what therapies would be considered options at this stage, and explaining their potential to produce the placebo effect.

To summarize, Tinnitus Stepped-Care is an efficient framework for both patients and clinicians (Henry, 2024c, 2026). Step 2 Audiology Services meets the needs of most patients who complain of tinnitus. If treatment is desired, they advance to Step 3 Tinnitus Education, which provides essential information to help them decide if Step 4 Tinnitus Counseling is desired. Those few patients who do not have their needs met through Step 4 can be offered the more intensive services in Steps 5 and 6. Patients with more severe tinnitus may require more intensive services from the very beginning. The order of steps is therefore flexible to meet individual needs.

18. There’s a lot of “buzz” about bimodal stimulation—how does that fit in with Tinnitus Stepped-Care?

Tinnitus Stepped-Care is a minimalistic approach that recommends only the minimum necessary services for individual patients. The approach is also patient-centered to focus on individual needs without making any assumptions. Any form of treatment, including bimodal stimulation, should adhere to these basic principles.

Bimodal stimulation, which is currently offered by two companies, involves two concurrent modes of stimulation (Khan et al., 2025). The approach is to use a specialized form of sound therapy that is synchronized with electrical or tactile stimulation with the purpose of enhancing any benefit received from the sound therapy (Conlon et al., 2020; Perrotta et al., 2023). One company combines sound and tongue stimulation into a scalable bimodal neuromodulation device (Boedts et al., 2024). The other company combines tones with synchronized vibrations on the wrist (haptic stimulation) (Perrotta et al., 2023). The companies do not claim to eliminate the sensation of tinnitus, hence they do not claim to cure tinnitus. Their goals of treatment are essentially the same as for methods of counseling and sound therapy—to reduce the effects of tinnitus and ultimately to habituate to the tinnitus.

As for all other methods of tinnitus treatment, a concern with bimodal stimulation is that these treatments have not been evaluated in trials that included a true placebo control group. It is thus a question if and how much the placebo effect might pertain to either of these methods.

Because of the expense involved in receiving treatment using bimodal stimulation, these therapies would generally be made available during Step 6 Expanded Treatment. Some patients, however, would choose to receive bimodal stimulation after they have received the Step 3 Tinnitus Education. If so, then bimodal stimulation could be offered as part of Step 4 Tinnitus Counseling.

19. Do any other companies offer specialized treatment for tinnitus?

Numerous companies offer products or apps for treating tinnitus. I’ll note a couple here; this is not an exhaustive list.

A specialized sound therapy device, consisting of a smartphone app and customized in-ear earbuds, is available for use only while sleeping (Theodoroff et al., 2017). The device can be used as the sole treatment for tinnitus or in conjunction with daytime treatment.

It’s been proposed that tinnitus may be a symptom of “atypical migraine,” i.e., non-headache-related central sensitivity (a sensory processing disorder causing the brain to become hypersensitive) (Djalilian et al., 2025). In such patients, treatments used for migraine may be used to treat tinnitus (Abouzari et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2023). A network of clinics provide this type of treatment via telehealth. Patients are counseled to make lifestyle modifications, including dietary changes, eating three meals a day, dietary supplementation, and sleeping on a regular schedule. Treatment also involves medications prescribed in a stepwise manner so that types and dosages are adjusted based on outcomes and side effects. This treatment regimen has been used to treat both tinnitus and hyperacusis.

The Tinnitus Stepped-Care book, provides a fairly complete summary of many diverse treatments that can be used to reduce effects of tinnitus (Henry, 2026).

20. What is your overall assessment of the field of tinnitus and where it is going?

As I've mentioned and it’s worth repeating: Tinnitus clinical services lack standardization because there is no oversight to establish consistency of these services. I believe audiologists should be the coordinators and main providers of tinnitus care. Unfortunately, assessment and treatment vary greatly between audiologists, and no mechanism exists to ensure the competency of services received.

The problem stems from the inconsistent training received by audiologists in their AuD graduate programs (Henry et al., 2021; Husain et al., 2018). Digging deeper, professional organizations for audiologists (primarily ASHA and AAA) have not established requirements for AuD programs to provide the necessary training, leaving it up to each program to determine if and to what extent such training is provided to their students.

Because of these gaps, people with tinnitus often don’t know how and where to receive appropriate care. For a condition that affects 10-15% of the adult population, this is an unacceptable situation.

Making the policy changes necessary to ensure adequate tinnitus training in AuD programs is my hope for the future. In the meantime, the short-term solution is a comprehensive training program endorsed by ASHA and/or AAA. The American Tinnitus Association could also contribute to the development of a training program.

What would a tinnitus training program look like? I envision the course containing different segments:

- Generic instruction on the fundamentals of tinnitus (“Tinnitus 101”) for all clinicians who encounter patients complaining of tinnitus

- Audiologist-specific training covering assessment procedures and treatment using established, evidence-based modalities (primarily TRT, TAT, and PTM)

- Training covering all/most of the methods of treatment for tinnitus that are currently offered (including experimental methods)

- Stress-reduction techniques that can be implemented by audiologists

- Mental health-specific training in traditional cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and third-wave CBT techniques (Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, mindfulness-based approaches)

- Clinical management of sound hypersensitivity disorders

An ASHA/AAA-accredited training program could, within a few years, greatly improve the landscape of tinnitus care provided by audiologists. Tinnitus Stepped-Care can serve as a model that would contribute toward achieving this outcome. Dedicated collaboration between tinnitus thought leaders and professional organizations is necessary to accomplish both the long-term and short-term goals. These goals are achievable if stakeholders have the will and commit to making the necessary effort.

References

Abouzari, M., Tan, D., Sarna, B., Ghavami, Y., Goshtasbi, K., Parker, E. M., Lin, H. W., & Djalilian, H. R. (2020). Efficacy of multi-modal migraine prophylaxis therapy on hyperacusis patients. Annals of Otology Rhinology and Laryngology, 129(5), 421-427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003489419892997

Beukes, E. W., Andersson, G., Manchaiah, V., & Kaldo, V. (2021). Cognitive behavioral therapy for tinnitus. Plural.

Beukes, E. W., Fagelson, M., Aronson, E. P., Munoz, M. F., Andersson, G., & Manchaiah, V. (2020). Readability following cultural and linguistic adaptations of an Internet-based intervention for tinnitus for use in the United States. American Journal of Audiology, 29(2), 97-109. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_AJA-19-00014

Boedts, M., Buechner, A., Khoo, S. G., Gjaltema, W., Moreels, F., Lesinski-Schiedat, A., Becker, P., MacMahon, H., Vixseboxse, L., Taghavi, R., Lim, H. H., & Lenarz, T. (2024). Combining sound with tongue stimulation for the treatment of tinnitus: a multi-site single-arm controlled pivotal trial. Nature Communications, 15(1), 6806. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50473-z

Chermak, G. D., & Dengerink, J. E. (1987). Characteristics of temporary noise-induced tinnitus in male and female subjects. Scandinavian Audiology, 16(2), 67-73. https://doi.org/10.3109/01050398709042158

Coles, R. R. A. (1984). Epidemiology of tinnitus: (2) Demographic and clinical features. Journal of Laryngology and Otology (Suppl. 9), 195-202.

Conlon, B., Langguth, B., Hamilton, C., Hughes, S., Meade, E., O’Connor, C., Schecklmann, M., Hall, D. A., Vanneste, S., Leong, S. L., Subramaniam, T., D'Arcy, S., & Lim, H. H. (2020). Bimodal neuromodulation combining sound and tongue stimulation reduces tinnitus symptoms in a large randomized clinical study. Science Translational Medicine, 12(564). https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abb2830

Dauman, R., & Tyler, R. S. (1992). Some considerations on the classification of tinnitus. In J.-M. Aran & R. Dauman (Eds.), Proceedings of the Fourth International Tinnitus Seminar (pp. 225-229). Kugler Publications.

Davis, A. C. (1995). Hearing in adults. Whurr Publishers.

Djalilian, H. R., Keum, D., Yazdani, Y., Abouzari, M., & Park, E. (2025, May 15). Cochlear migraine: Exploring migraine’s impact on the auditory system. Bulletin. https://bulletin.entnet.org/home/article/22940987/cochlear-migraine-exploring-migraines-impact-on-the-auditory-system.

Dobie, R. A. (2004). Overview: Suffering from tinnitus. In J. B. Snow (Ed.), Tinnitus: Theory and management (pp. 1-7). BC Decker Inc.

Fioretti, A. (2025). Advances in tinnitus and hearing disorders. Brain Sciences, 15(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15060553

Hazell, J. W. P. (1995). Models of tinnitus: Generation, perception, clinical implications. In J. A. Vernon & A. R. Moller (Eds.), Mechanisms of tinnitus (pp. 57-72). Allyn & Bacon.

Henry, J. A. (2016). “Measurement” of tinnitus. Otology and Neurotology, 37(8), e276-285. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000001070

Henry, J. A. (2024a). The tinnitus book: Understanding tinnitus and how to find relief. Ears Gone Wrong, LLC.

Henry, J. A. (2024b). The tinnitus retraining therapy book: Walking you through TRT. Ears Gone Wrong, LLC.

Henry, J. A. (2024c). Tinnitus stepped-care: A model for standardizing clinical services for tinnitus. Seminars in Hearing, 45(03-04), 255-275. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0045-1804509

Henry, J. A. (2025a). The hyperacusis and misophonia book: When everyday sounds are too loud, distressing, or painful. Ears Gone Wrong, LLC.

Henry, J. A. (2025b). The progressive tinnitus management book: Step-by-step through the five levels of PTM. Ears Gone Wrong, LLC.

Henry, J. A. (2026). Tinnitus Stepped-Care: A standardized framework for clinical practice. Plural Publishing.

Henry, J. A., Goodworth, M. C., Lima, E., Zaugg, T., & Thielman, E. J. (2022). Cognitive behavioral therapy for tinnitus: Addressing the controversy of its clinical delivery by audiologists. Ear and Hearing, 43(2), 283-289. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000001150

Henry, J. A., Griest, S., Austin, D., Helt, W., Gordon, J., Thielman, E., Theodoroff, S. M., Lewis, M. S., Blankenship, C., Zaugg, T. L., & Carlson, K. (2016). Tinnitus screener: Results from the first 100 participants in an epidemiology study. American Journal of Audiology, 25(2), 153-160. https://doi.org/10.1044/2016_AJA-15-0076

Henry, J. A., Griest, S., Zaugg, T. L., Thielman, E., Kaelin, C., Galvez, G., & Carlson, K. F. (2015). Tinnitus and hearing survey: A screening tool to differentiate bothersome tinnitus from hearing difficulties. American Journal of Audiology, 24(1), 66-77. https://doi.org/10.1044/2014_AJA-14-0042

Henry, J. A., Reavis, K. M., Griest, S. E., Thielman, E. J., Theodoroff, S. M., Grush, L. D., & Carlson, K. F. (2020). Tinnitus: An epidemiologic perspective. Otolaryngology Clinics of North America, 53(4), 481-499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2020.03.002

Henry, J. A., Sonstroem, A., Smith, B., & Grush, L. (2021). Survey of audiology graduate programs: Training students in tinnitus management. American Journal of Audiology, 30(1), 22-27. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_AJA-20-00140

Henry, J. A., Zaugg, T. L., Myers, P. J., Kendall, C. J., & Michaelides, E. M. (2010). A triage guide for tinnitus. Journal of Family Practice, 59(7), 389-393. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20625568

Husain, F. T., Gander, P. E., Jansen, J. N., & Shen, S. (2018). Expectations for tinnitus treatment and outcomes: A survey study of audiologists and patients. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 29(4), 313-336. https://doi.org/10.3766/jaaa.16154

Jastreboff, P. J., & Hazell, J. W. P. (2004). Tinnitus retraining therapy: Implementing the neurophysiological model. Cambridge University Press.

Khan, A. A., Nasim, H., Manhal, G. A. A., & Abbasher Hussien Mohamed Ahmed, K. (2025). Exploring the therapeutic potential of bimodal stimulation for tinnitus. Annals of Medicine and Surgery (London), 87(3), 1105-1108. https://doi.org/10.1097/MS9.0000000000002998

Kimball, S. H., Johnson, C. E., Baldwin, J., Barton, K., Mathews, C., & Danhauer, J. L. (2018). Hearing aids as a treatment for tinnitus patients with slight to mild sensorineural hearing loss. Seminars in Hearing, 39(2), 123-134. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1641739

Lee, A., Abouzari, M., Akbarpour, M., Risbud, A., Lin, H. W., & Djalilian, H. R. (2023). A proposed association between subjective nonpulsatile tinnitus and migraine. World Journal of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 9(2), 107-114. https://doi.org/10.1002/wjo2.81

Levine, R. A., & Lerner, Y. (2021). Sudden brief unilateral tapering tinnitus (SBUTT) is closely related to the lateral pterygoid muscle. Otology & Neurotology, 42(6), e795-e797. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000003090

Meikle, M., & Taylor-Walsh, E. (1984). Characteristics of tinnitus and related observations in over 1800 tinnitus clinic patients. Journal of Laryngology and Otology Supplement, 9, 17-21. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1755146300090053

Miao, W., Wu, C., Yuan, D., Li, Y., & Wu, T. (2025). Association between atherogenic index of plasma and tinnitus: evidence from NHANES and the mediating role of hypertension. Lipids in Health and Disease, 24(1), 283. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-025-02716-1

Norman, M., Tomscha, K., & Wehr, M. (2012). Isoflurane blocks temporary tinnitus. Hearing Research, 290(1-2), 64-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2012.03.015

Perez, A. P., Garcia-Antelo, M. J., & Rubio-Nazabal, E. (2017). “Doctor, I hear music”: A brief review about musical hallucinations. The Open Neurology Journal, 11, 11-14. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874205X01711010011

Perreau, A., Tyler, R. S., Mancini, P. C., & Witt, S. A. (2022). Tinnitus activities treatment. In R. S. Tyler & A. Perreau (Eds.), Tinnitus treatment: Clinical protocols (pp. 42-70). Thieme.

Perrotta, M. V., Kohler, I., & Eagleman, D. M. (2023). Bimodal stimulation for the reduction of tinnitus using vibration on the skin. International Tinnitus Journal, 27(1), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.5935/0946-5448.20230001

Quaranta, A., Portalatini, P., & Henderson, D. (1998). Temporary and permanent threshold shift: An overview. Scandinavian Audiology Supplement, 48, 75-86. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9505300

Ratnayake, S. A., Jayarajan, V., & Bartlett, J. (2009). Could an underlying hearing loss be a significant factor in the handicap caused by tinnitus? Noise and Health, 11(44), 156-160. https://doi.org/10.4103/1463-1741.53362

Simpson, T. H. (1999). Occupational hearing loss prevention programs. In F. E. Musiek & W. F. Rintelmann (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives in hearing assessment (pp. 479-484). Allyn & Bacon.

Theodoroff, S. M., McMillan, G. P., Zaugg, T. L., Cheslock, M., Roberts, C., & Henry, J. A. (2017). Randomized controlled trial of a novel device for tinnitus sound therapy during sleep. American Journal of Audiology, 26(4), 543-554. https://doi.org/10.1044/2017_AJA-17-0022

Thielman, E. J., Reavis, K. M., Theodoroff, S. M., Grush, L. D., Thapa, S., Smith, B. D., Schultz, J., & Henry, J. A. (2023). Tinnitus screener: Short-term test-retest reliability. American Journal of Audiology, 32(1), 232-242. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_AJA-22-00140

Tunkel, D. E., Bauer, C. A., Sun, G. H., Rosenfeld, R. M., Chandrasekhar, S. S., Cunningham, E. R., Jr., Archer, S. M., Blakley, B. W., Carter, J. M., Granieri, E. C., Henry, J. A., Hollingsworth, D., Khan, F. A., Mitchell, S., Monfared, A., Newman, C. W., Omole, F. S., Phillips, C. D., Robinson, S. K., . . . Whamond, E. J. (2014). Clinical practice guideline: Tinnitus. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, 151(2 Suppl), S1-S40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599814545325

Xiong, B., Liu, Z., Liu, Q., Peng, Y., Wu, H., Lin, Y., Zhao, X., & Sun, W. (2019). Missed hearing loss in tinnitus patients with normal audiograms. Hearing Research, 384, 107826. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2019.107826

Citation

Henry, J. A. (2026). 20Q: Adopting tinnitus stepped-care as standard practice. AudiologyOnline, Article 29532. Available at www.audiologyonline.com