From the Desk of Gus Mueller

From the Desk of Gus Mueller

Although listening effort has been studied for decades, there is still much to learn—a perfect topic for an audiology column titled “20 Questions.” For starters, there probably are 10 or more different ways to measure it. Which ones are the best? General categories include physiological, behavioral, and self-report measures. They all have been reported to be somewhat successful in identifying the degree of listening effort. Do these different measures agree? Not as well as we would like. Maybe the different measures represent different dimensions of listening effort?

We would expect that listening effort would increase as the task becomes more difficult—often this is because of the presence of background noise. While logical, this might not always apply, as with many hard of hearing individuals, there is a point when they just “give up,” and effort is then reduced. Even those of us with normal hearing sometimes find that to understand certain actors in a movie requires more effort than we just want to expend—and we look for an alternative movie (or turn on closed captions).

And, there is also the issue of motivation to succeed. We know from hearing aid studies, that when individuals are told that they are listening with “new technology” hearing aids (when they are not), their word recognition scores improve. More effort, or something else? We could go on, but better to turn things over to an expert in the area.

Matthew Winn, PhD, AuD, is an associate professor of audiology at the University of Minnesota. He directs the Listen Lab, which focuses on speech communication and the factors that make it effortful for people with hearing loss – especially those with cochlear implants. Over the past decade, through his many publications and presentations on the topic, he has distinguished himself as an opinion leader in the important area of listening effort.

Dr. Winn has been awarded several grants from the NIH-NICDC, and his publications have earned several awards; most recently the 2023 Editor’s Award for best article in the Hearing Section of JSLHR, and the 2024 Editor’s Choice Award from Ear and Hearing. He has served as Associate Editor of Ear and Hearing, Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, and Trends in Hearing.

In Matt’s excellent 20Q review, he describes why an understanding of listening effort is important for the clinician. He states that

“the biggest benefit is gaining the patient’s trust, which will ensure that your clinical advice is taken to heart. When you talk about listening effort with your patients, you signal to them that you are trying to recognize and understand a big part of their lived experience. When patients feel understood, they might be more likely to appreciate your advice and trust your recommendations.”

I agree!

Gus Mueller, PhD

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller CEU articles at www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: Listening Effort – Understanding its Role in Audiology and Patients' Lives

Learning Outcomes

After reading this article, professionals will be able to:

- Express how understanding effort adds value to clinical practice.

- Explain to patients how listening effort affects health, work, and family life.

- List factors that reduce listening effort for people with hearing loss.

1. I already routinely measure auditory thresholds, word recognition, middle-ear function, and other things. What do I gain as a clinician by also learning about listening effort?

I believe that the biggest benefit is gaining the patient’s trust, which will ensure that your clinical advice is taken to heart. When you talk about listening effort with your patients, you signal to them that you are trying to recognize and understand a big part of their lived experience. When patients feel understood, they might be more likely to appreciate your advice and trust your recommendations. I’m thinking about patients who become frustrated with hearing aids in the first week and just toss them into the drawer because they don’t feel committed. If you establish that you are firmly on their side and can understand the challenges that they feel, this might strengthen their enthusiasm to take advantage of all the training and experience that you have to offer.

One of the best strategies I keep in mind is to aim for head nods. If I talk about a situation like “you know how you miss one word and then as you’re trying to figure it out, they are already on to the next sentence?”, I get so many enthusiastic head nods and people saying “yes! you understand”. That’s when I know they trust me to sympathize with their experience.

Only after this big-picture connection do I think about the potential diagnostic value of effort, like determining if a borderline hearing aid candidate is struggling with more effortful listening and using that to help determine candidacy… or seeing if a hearing aid lowers a person’s perceived effort.

2. Is it safe to assume that my patients with lower word recognition scores are the ones exerting the most effort?

Surprisingly, no – we can’t know someone’s effort just from knowing their word recognition score. There are two ways that we know this. The first is from a combination of lab studies. A patient could get a correct answer after exerting more effort, because they were mentally repairing a word within a sentence. We have also shown that there are situations where a person might get something wrong and exert less effort because they have no reason to suspect that they are wrong. So, accuracy and effort can sometimes go in opposite directions.

The second way we know this is more interesting. For someone with lower speech recognition ability, they might be exerting very little effort because listening is so difficult that the effort is not worth it. So we want to be careful not to just think that low effort equals success, because avoidance isn’t the goal.

3. Okay, but if effort isn’t clear from the speech scores, then how does effort show up?

Effort shows up in a lot of interesting ways that seem at first to be unrelated to hearing. Think of it as knowing there is a fire because you see the smoke; effort makes itself known from the other downstream consequences. For example, a person might have difficulty multi-tasking, or not be willing or able to spend as much time listening. They might rally hard to focus for an important conversation, and then suffer consequences later, like drifting off in the next meeting, or not having the energy to clean the house once they get home. One patient told me that she uses more paper plates because she didn’t have the energy to do dishes. Although we don’t normally ask about household chores during audiology case histories, these are the outward signs of listening fatigue.

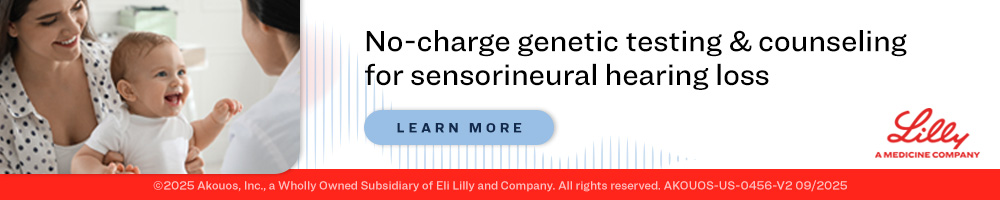

Sometimes a person will struggle so much with listening that they limit the situations they are willing to engage in. As an audiologist, you might recognize this as the conundrum of the hearing aid follow-up appointment: you ask the patient how the restaurant noise-reduction program is working, but he doesn’t have an answer because he has learned to avoid noisy restaurants, so he never tested the devices in that situation. We have to probe indirectly to see if the patient’s listening world has been limited, by asking about the activities that our patients are willing to engage in, and how they might have changed compared to a previous time when they had better hearing. This is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Two people might both report that they do not experience much listening effort in their daily lives. But that might be because one of them has limited the range of listening activities that he is willing to engage in, or because he has stopped doing effortful things because his hearing is covertly draining his energy.

4. What’s a good first step in incorporating listening effort in my clinical appointments?

The first step is a clever set of case-history questions about a person’s willingness to engage in various activities – especially if they once had normal, or near-normal hearing and no listening-related constraints. Comparing the present to the past could highlight how a person has constrained their listening world over the years. Ask about the work it takes to focus, and how long they feel tired after focused listening.

It’s important to know that patients might use different words to talk about listening effort, like stress, strain, anxiety, embarrassment, disconnection, and fatigue. There is a wide variety of relevant experiences

Thankfully, there are validated surveys that can help you ask about effort. I am excited about two in particular. The first is the Cochlear Implant Quality of Life (CIQoL) tool, developed by the team at the Medical University of South Carolina. The reason I’m fond of this method is that it highlights real-world abilities rather than relying on simple clinical tests. It also happens to show that listening effort is strongly related to patients’ reported quality of life.

The second tool I like is the listening effort questionnaire-cochlear implant (LEQ-CI), developed by Sarah Hughes and her team in the UK and Australia. What I like about this is that it was driven by patients themselves (rather than being driven only by people who have typical hearing), and was refined using exacting methods to improve the power of the questionnaire to detect effort in a meaningful way.

We are probably not going to take physiological measures like heart rate, pupil dilation, brain imaging, etc. in the clinic, but these survey methods can be useful for tracking effort and also in making patients aware of their own effort by highlighting it in our clinical conversations.

As you noticed both of these self-report scales have “cochlear implant” in their titles. This is a little misleading for our discussion here, as these scales are not limited to the CI patient population. But I’m deep into the CI world, so these are the tools that have caught my attention, and which I have been able to understand more deeply. The basic concepts in these scales can generalize across a wide variety of patients that you would encounter. An example of a more general listening effort scale is called ACALES (Adaptive Categorical Listening Effort Scaling), developed by Malanie Krueger and colleagues. This allows the patient to report their subjective effort with detail. The one piece of caution that I would advise on this scale though, is that there is sometimes confusion between extreme effort and no effort, even though those are at opposite ends of the ACALES interface. Specifically, it is tempting for a person to experience an extremely difficult listening condition and report that extreme difficulty, even if their effort was minimal because they actually gave up on the task. Clear instructions are key.

5. You’re telling me that patients need to be made aware of their own effort?

This seems so paradoxical right? But it’s true – some patients are not even aware of their own listening effort. There are two main reasons for this. First, they might attribute their stress and fatigue to things other than hearing. But also, they might have adapted to their effort by simply avoiding hard listening situations.

Sometimes, after intentionally planning and managing listening effort does a person realize the impact it can have. I’ve learned lessons about this process by listening to vocal hearing loss advocates like Gael Hannan, Shari Eberts, Sarah Sparks, and others who are active on social media, and the people who come into my lab. Based on what they have said, I would encourage audiologists to counsel patients to notice behaviors after listening, notice behaviors during listening, and to think long-term about how behaviors have been modified over the years. Have the patient ask their family and friends about the ways their hearing impacts social dynamics, and coach them on how to not be defensive when the family gives an honest response.

6. In recent years, we’ve all heard about the connection between hearing loss and dementia. Is there an associated connection with listening effort?

Although we know that untreated hearing loss is associated with increased risk of cognitive decline, we have not established exactly what links them together. It’s tempting to think that a person might overwork their brain from too much effort, but the more popular idea is that the decline results from social isolation because people avoid those stimulating situations where listening would be too effortful.

People should be cautious about how this idea is framed by marketing teams who want to capitalize on our fear of aging and decline. If anyone gives the impression that they have a clear solution to this issue, they are not being honest.

7. You mentioned the self-assessment inventories, but are there more objective ways to assess listening effort?

In the research laboratory, there are lots of good objective measurements. In addition to just asking someone about their effort, we can observe longer reaction times – especially when a person is multitasking – as well as increased pupil size, and increased slow brain oscillations called alpha waves. Also, since effort is related to stress, the normal signs of stress (like increased heart rate and sweaty palms) can also be used as signs of effort. Each of these methods has pros and cons.

8. I’m not familiar with pupillometry. Could we bring that method into the clinic to measure effort?

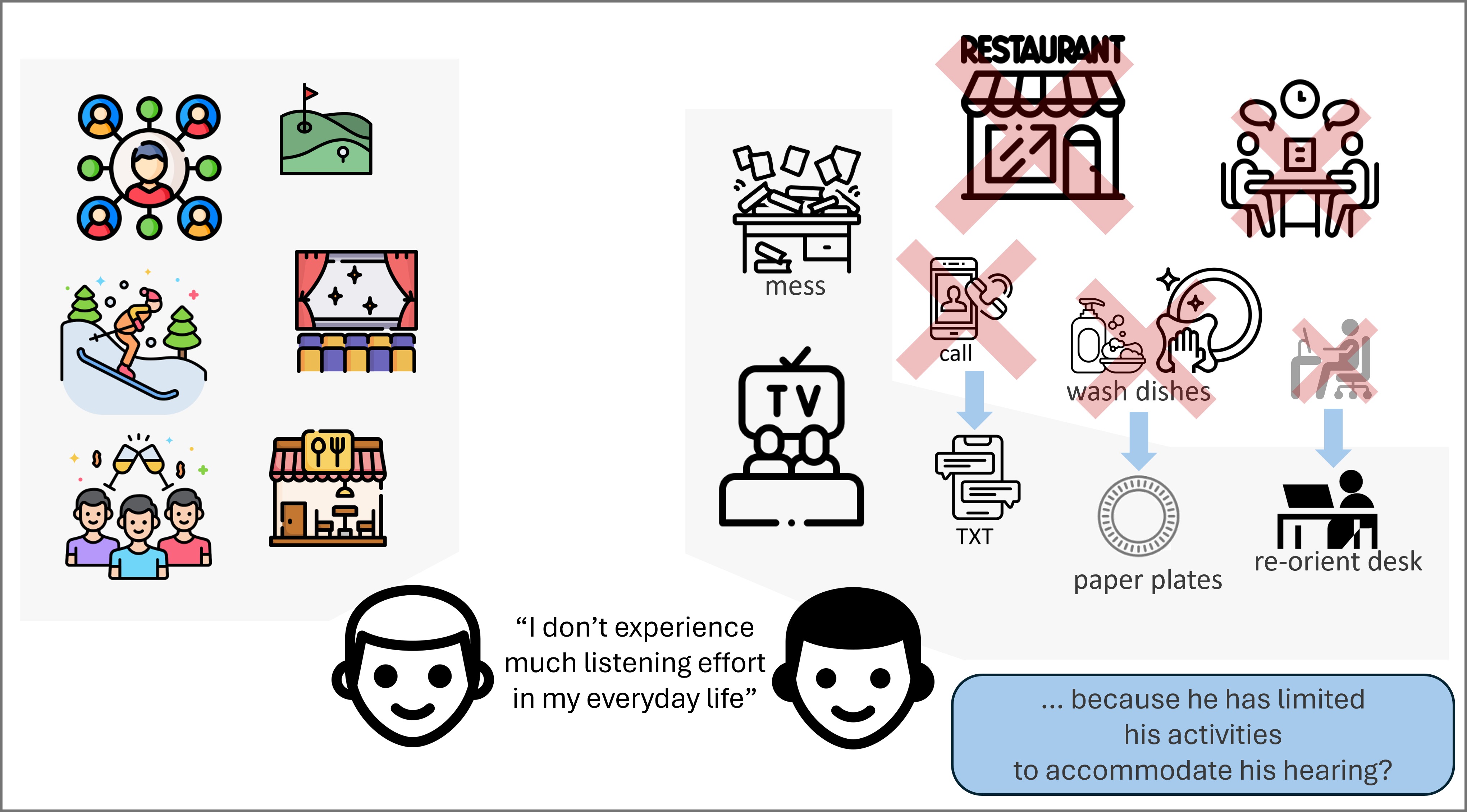

Here is a quick review of pupillometry, and how it’s conducted:

The main idea is that a small camera records changes in a person’s pupil size as they respond to key events, like hearing sentences. Just as we do for an ABR, we have to take a large number of trials and align the data to a landmark like the start or the end of the sentence. We expect that if condition A is harder than condition B, then you will get larger pupil dilations for condition A. There are a lot of interesting details about how quickly the pupil gros, how slowly it returns back to normal size, and how precisely the dilations correspond to the key speech events, but that is the main idea. One of the challenges with pupillometry is that general arousal or the brightness of the room lighting can influence pupil size in a way that does not directly reflect listening effort. For this reason, we have to exert a lot of control over the testing environment and the pacing of the test, what the person expects, and average the data over many trials. Figure 2 shows a little illustration of the main ideas in a simplified way.

Figure 2. Main concepts in conducting pupillometry

Compared to other measures of listening effort, pupillometry has some major advantages, like being non-invasive and being entirely unaffected by electronics like hearing aids and cochlear implants (these devices can really complicate various brain imaging techniques). It also gives us data in a time series rather than a singular point, which means we can see how effort changes moment by moment as the listener converts words into meaning. This turns out to be very good when you have questions about processing sentences, but not so good if you are interested in the effort exerted across a whole day (because the person’s overall alertness and relationship to the environment will change dramatically in a way that affects the pupil even if their effort is not changing).

To more directly answer your question, although I have a lot of optimism about how this research will continue to raise awareness of listening effort in audiology, I don’t expect that we will be able to use pupillometry in the clinic. To be clinically useful, the measurement has to be easy to execute, easy to analyze and interpret, and has to give you information that you can compare from one appointment to the next. Pupillometry doesn’t give us any of those things. It requires some serious technical analysis skills to handle the data, and very restrictive controls on the listening environment like controlling brightness of the room and the direction of the eye movements. Testing time can be very long because analysis requires averaging lots of trials together with sufficient time in between to let a person come back to a standard state of readiness. It requires time-locked listening events averaged across about 30 repetitions. Also, we’re not at a point where we have established cross-session test-retest reliability, so we can only really solidly analyze within-session results.

So at this time I think it’s best to think of pupillometry as a laboratory technique that can teach us important lessons when using very tightly-controlled methods, rather than a clinical tool.

9. Okay. With all those constraints, what has been learned about listening effort using pupillometry?

The main value is learning how effort changes moment-to-moment as a person is listening – like how they predict words, or dwell on words that they missed. For example, we have learned that contextual words alleviate effort extremely rapidly for people who have normal or near-normal hearing – there is a reduction in pupil dilation if there is context, even while the sentence is still being heard. However, for people who use cochlear implants, that benefit of context is slower – for them, context still relieves effort, but mainly after the sentence is over – it’s as if they are gathering the information and then working backwards to figure it out. This whole process happens too fast for the person to be able to describe it accurately if we give them a survey.

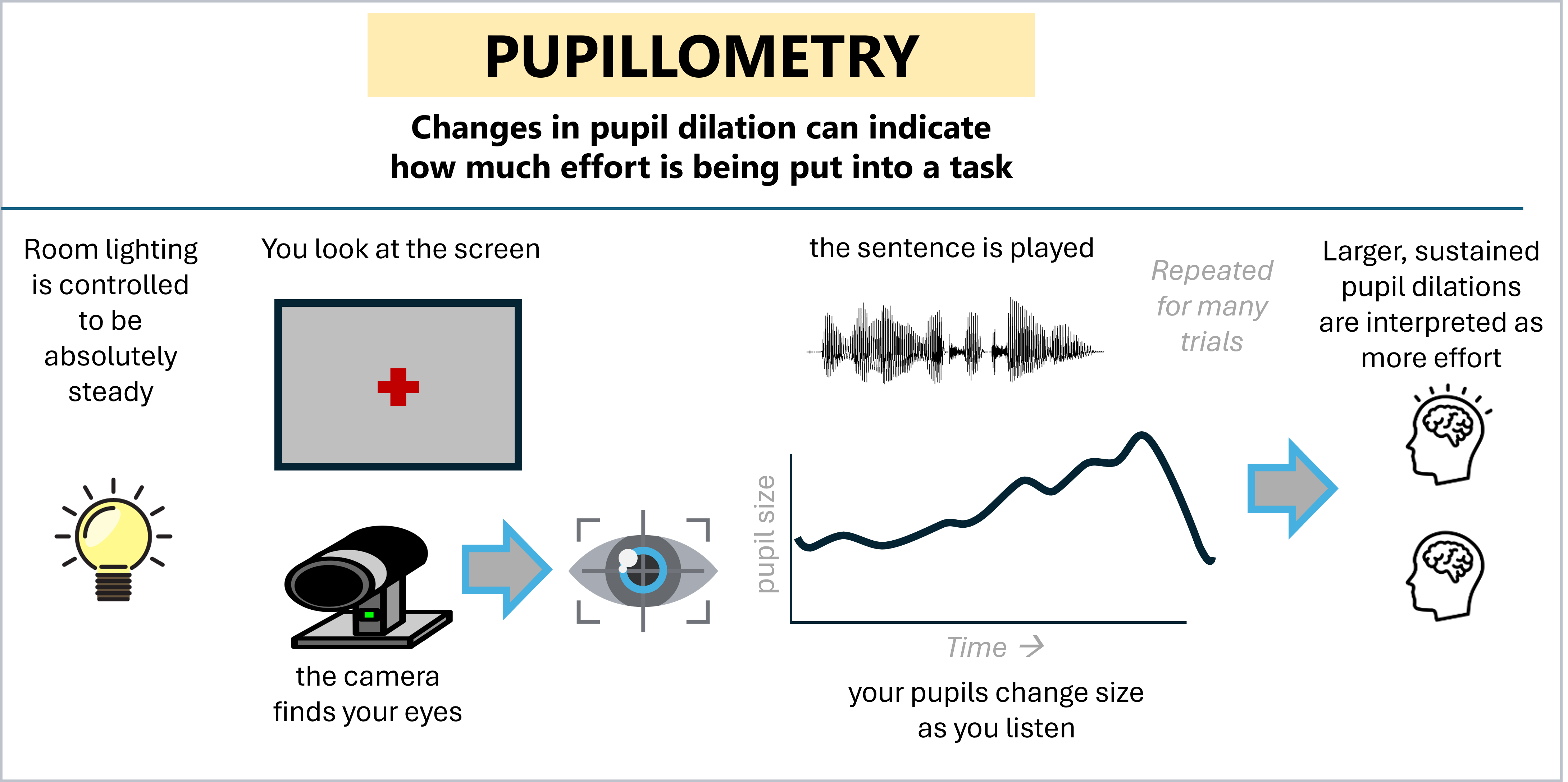

Another important lesson we have learned is that the process of figuring out a word using context is not only effortful, it can also put you at risk for missing the next few words. The way we observed this was to present sentences where a single word early in the sentence was replaced with noise and inferred using later context, like “we ate [ ... ] with cheese and pepperoni” – you can figure out that it was pizza, but in the process of figuring it out, you might mis-remember which toppings were mentioned. For listeners with cochlear implants, the effort of that mental repair carried forward for several seconds after the sentence was over, as if they were still pondering it. They were more likely to miss some of the words right after the sentence, suggesting they were “stuck” on the last thing they heard. This is what I am illustrating in Figure 3.

The main story that has emerged from our lab over the past 5 years is that even if people with hearing loss are not exerting more effort, they tend to exert effort for longer periods of time, which is problematic when conversational speech moves fast.

Figure 3. Carryover effort is when the mental work of repairing a word in one sentence interferes with your ability to hear later words, like the start of the next sentence.

Here's why I think these experiments have real value: in the clinic, we give the patient one utterance at a time – a single word, or a single sentence. If the patient takes an extra moment to fill in a missing piece or to figure out how the words make sense, then we wouldn’t know it because we pause and give them a chance to assemble their answer and respond before the next sentence begins. In real life, we usually don’t have that opportunity. So the patient who looks like they are doing fine in the booth might be using a mental repair strategy that would not work in a regular flowing conversation. We know that people with hearing loss will benefit from an extra moment to process after a sentence was spoken (Steven Gianakas showed this in his 2023 paper), so we can translate that into real-world advice: pause after key information to ensure that the listener can assemble it into a solid thought. Otherwise, there will be mental competition between the last thing you said and the next thing you say.

10. But when I am doing word-recognition testing in the booth, I can notice when a patient seems slow or unsure when they repeat the words. Is that good enough?

This is a tempting thought, but in general, we have very poor ability to detect whether someone is exerting extra listening effort, for a variety of reasons. First, people are very well practiced at hiding their effort, because they might not want to risk the flow of conversation by interrupting you to repeat a word. Some people would rather give the “deaf nod” and go with the flow rather than express uncertainty.

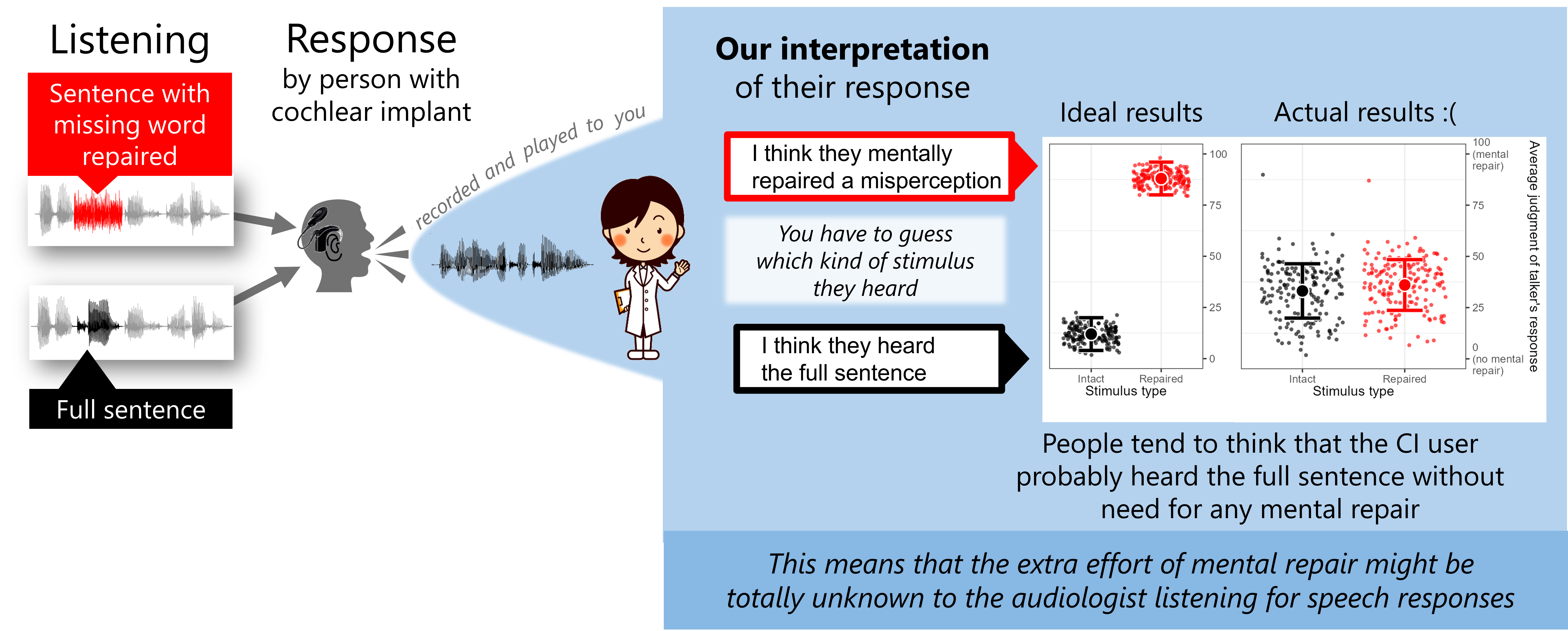

We actually conducted a study on this, which I am illustrating in Figure 4. Earlier, I mentioned the experiment where CI users heard sentences that were either fully intact or required a word to be repaired along the way. We took audio recordings of their vocal responses (with their permission!) and played them back to new listeners who had to guess whether the CI user was responding to an easy (intact) or a hard (repaired) sentence. The results were dismal – there was a general tendency for external observers to assume that the CI user heard a full sentence and there was no reliable detection of the extra effort – even by people who claimed expertise in detecting confusion in a person’s voice, and even by a group of practicing audiologists. This means there is probably a lot of extra effort that we are not noticing.

Figure 4. It is difficult to recognize when a person is mentally repairing words that they missed. We expected that the effort of mentally repairing words would be evident in the voice of CI users who were asked to repeat sentences. However, when playing back audio recordings of their voice (as an audiologist would hear them in the booth), there was no sign that people are able to detect this effortful process just by listening to the person’s voice.

11. Can we assume that the “objective” measurement of effort will correspond to the patient’s own subjective rating of their effort?

Good question. In fact, there has been some research showing that they often do not agree. At first glance this looks like a disappointing result, but it turns out to be a valuable observation. When we learn that there are different kinds of intelligence (musical, spatial, verbal, emotional, etc.), or various kinds of athletic abilities (throwing a dart accurately, skating fast, jumping high, serving a tennis ball, etc.), we don’t get frustrated at this; our understanding deepens. Listening effort has different dimensions, and we gain better understanding by appreciating that some aspects of effort are felt by the individual, and some aspects of effort show signs but are not felt. Sara Al-Hanbali and Callum Shields both showed this concept in separate studies, so we *expect* results to go in different directions depending on what was measured.

Asking a person about their effort is complicated, because they can interpret the question to relate to how hard they tried, or to their estimate of how well they scored. They might just report their level of frustration. They might give you a rating of how annoying they find the background noise. They might report that they were nervous to perform well. These are all separate concepts, right? Depending on what’s on a person’s mind when you ask about their effort, they might be serving a tennis ball when you really want them to throw a dart.

When you measure something objectively, some of these concerns are lessened because we are all generally working with the same biological hardware. You can measure how much arousal or stress someone went through, and you can see how it changed moment-to-moment as they listened (a process that is too fast to be remembered and recalled accurately).

So I think we can look at objective and subjective effort measures as tapping into two very different things – the physiological resource depletion, and the awareness and evaluation of that resource depletion, respectively.

12. Considerably more complex than I would have guessed. Are there any new insights about how people report subjective effort?

Yes! One of my favorite results, reported recently, was found by Alex Francis and his team at Purdue. They are interested in how background noise affects things like effort and frustration. In conditions where the background noise was challenging but manageable, listeners enjoyed a reduction in frustration when they felt a sense of control over the noise. This is a departure from the typical way that lab studies are conducted, where the experimenter is in full control and the listeners merely respond to whatever situation they are put in. In addition to the main result that they found, I like how this raises awareness of the basic fact that people with and without hearing loss often do have an ability to control their situation by reorienting their head or body position, coaching their conversation partner, or by simply leaving the situation. It highlights how frustration might stem from a feeling of helplessness rather than pure listening difficulty.

13. Can we learn more about listening effort from new technological advances and big data?

In general, the bigger the data, the simpler the data. Large databases of audiometric outcomes are limited to things that are easy and quick to measure. For example, pure-tone thresholds and recognition scores for single words, or responses to one or two survey questions. These are unlikely to give useful insight into listening effort. Personally, whether it’s five hundred, five thousand, five million data points, there’s no number of pure-tone thresholds that can be translated into an index of whether a person is spending too much effort to understand speech – and if they are even willing to engage in that process at all.

However, there are still some things we can learn, or at least be inspired by. The team at Johns Hopkins has collected data from a very large sample of people, finding that hearing difficulty is related to various measures of social connection, mental health, risk for depression, etc. So I think that the major role of big data in audiology is not to find final answers to these questions, but instead to find the hints that would lead to good prospectively designed studies.

14. What are some factors that can reduce listening effort?

I really like this question because so much of hearing research is just “look, here’s another thing that people with hearing loss struggle with”. Kate Teece worked with me on a study that showed slower speaking rate can reduce effort – particularly for the purpose of using contextual information. Effort is also significantly reduced if a person has advance knowledge of what someone will be talking about (this work was done by my first PhD student, Steven Gianakas!)

Effort is also alleviated when you have contextual information within the sentence itself. For example, hearing “it’s raining outside, so bring your …” allows your brain to work less hard to hear the word “umbrella”. The context doesn’t just improve accuracy, it allows the brain to make predictions, and we can agree that deciding between the small list of options like “coat” or “umbrella” is less effortful than being vigilant for every possible word.

Recall earlier how I said that mentally repairing a word demands extra effort that can last long? Well, Justin Fleming recently completed an experiment where visual cues rescued listeners from the effort of this repair process by helping them “wrap up” their perceptions earlier. This study was interesting because it suggested that the benefit of visual cues might not be fully appreciated unless you measure these moments of increased workload, like repairing words.

15. Can hearing aids reduce listening effort?

The evidence says yes! My favorite example is a study by Ben Hornsby that was published in 2013. He showed that when listeners are engaged in an hour of listening, their reaction times gradually get slower and slower, and their ability to multitask deteriorates. But when those same individuals are fit with hearing aids, their reaction times and multitasking abilities are rather well preserved. Imagine how much more someone can get done if the brain isn’t dragged down by the effort of listening. However, there is an interesting catch: this study and another one by Jamie Desjardins (2016) suggest that these multitasking benefits can appear even if the individual listener does not feel a change in perceived effort. So it’s important to make measurements and not just ask about subjective impressions.

Several other studies have demonstrated that hearing aid features like noise reduction can reduce listening effort (Wendt et al. 2017, Fiedler et al. 2021).

Here’s what I think is the most interesting: it’s possible that the benefit of noise reduction is indirect, in a way you might not expect. Noise reduction appears to reduce the *annoyance* of a sound (Brons et al. 2013; Wong et al. 2018; Francis 2022). So I think that noise reduction might free up the brain power that would have otherwise been used to separate speech from noise, or to simply handle the annoyance of the noise… so that the listener can use that brain power to fill in missing gaps, predict upcoming words, more solidly encode the words into memory, or think of a fun creative response in conversation.

16. What is the trickiest thing to grasp about listening effort?

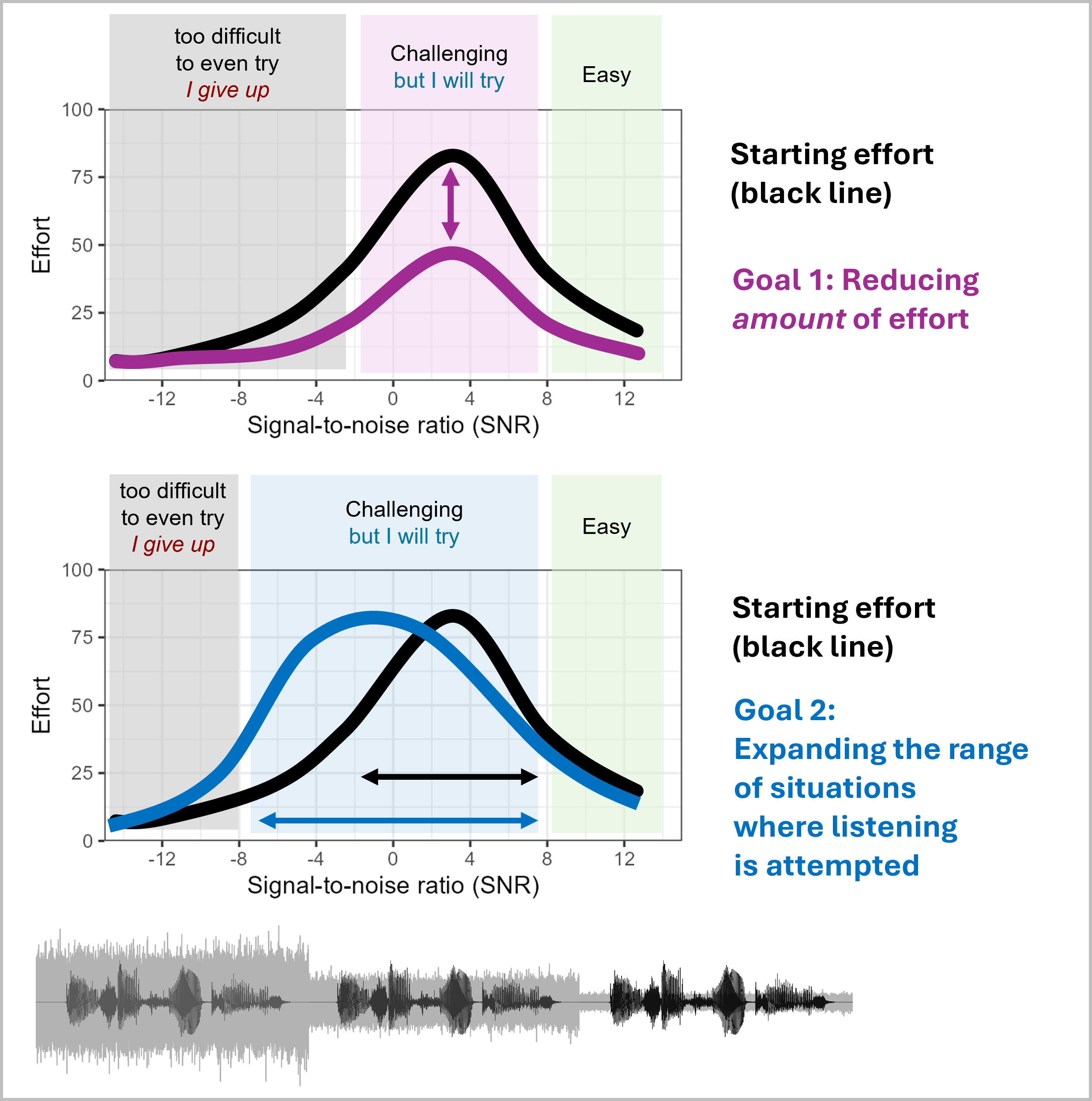

This is going to sound odd… but the tricky thing about effort is that we don’t want to minimize it. At first glance, this might be confusing because you would think minimal effort means everything is easy to hear, right? But on the other hand, quality listening is engaging, and if you’re putting in minimal effort, it might be a sign that you have given up because you don’t think you even have a chance (Dorothea Wendt had an excellent study showing this concept). If any of my students put in minimal effort, I wouldn’t assume that they are a virtuoso – I would be concerned that they are disengaged. When people give up on their hearing, they disconnect from those around them. So I think we should be cautious anytime someone talks about “minimizing” effort. Instead, I would say that another solid goal would be to expand the situations in which a person is willing to put in their effort at least try to listen. If we expand that range of situations, we could open someone up to a world of connections that they have been missing for years.

This is what I am trying to illustrate in Figure 5. Most of us assume Goal #1, which is to reduce effort. We should also strive for Goal #2, which is to expand the range of situations where the patient would be confident enough to try to listen.

Figure 5. Two ways of thinking about listening effort goals. Goal 1 is to seek reduction of effort across all situations. Goal 2 is to expand the range of situations where listening is attempted (effort is a sign of willingness to engage).

17. What do we know about effort in the pediatric population?

Listening effort can be harder to measure in children, depending on their abilities, their patience, and their ability to remain calm during testing. In school-age children, reaction times and subjective ratings are more common compared to physiologic measures like pupil dilation or heart rate, because children can be less willing to sit still and remain attentive for long stretches of time.

A recent study by Julia Seitz was set up in a way that I really like. She and her team set up children aged 6 to 10 in a simulated classroom environment, where they had to hold an item in memory as they recognized words in noise. As the noise (and reverberation) increased, the items were more likely to fall out of their memory, presumably because the primary speech task required more effort to process.

Earlier, I mentioned how understanding a patient’s listening effort requires some clever questioning that doesn’t always obviously relate to hearing. With children, you might ask about willingness to do after-school activities, as a window into the effort that a child is using at school.

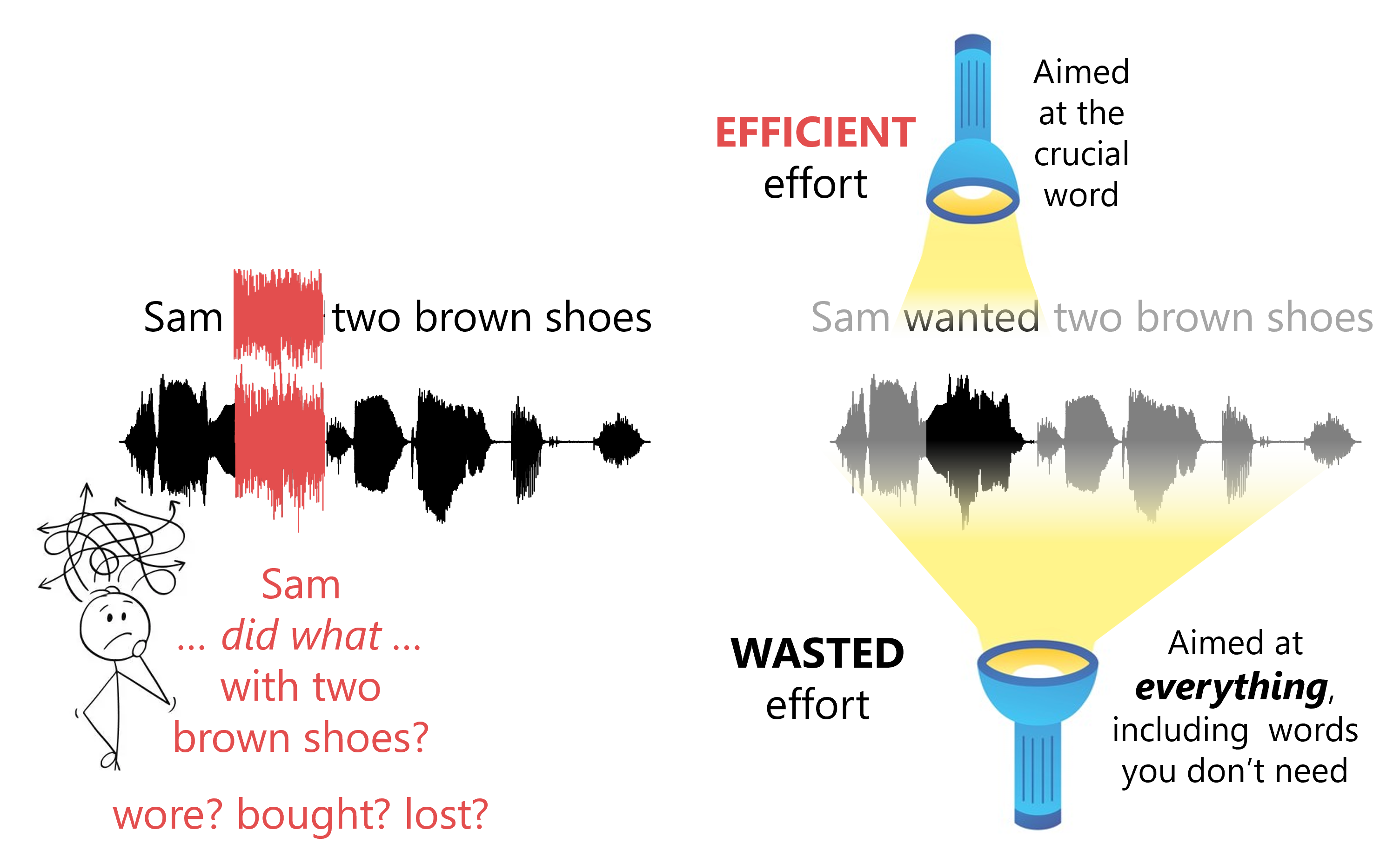

18. Are there some new areas of listening effort that your lab is working on?

We are really interested in whether people can “aim” their effort strategically, which is a concept that you can see in Figure 6. So far in preliminary studies, we have found that people with normal or near-normal hearing can aim effort at key words that they need, and reduce effort when they hear words that they don’t need. However, our CI listeners show a different pattern – they seem to be spreading their effort into places where it is not obviously useful. For example, the NH listeners will show pupil dilations at specific points in time where they need key information, but CI listeners show these dilations even where the speech can be ignored, or where it has already been heard. When we give NH listeners the same sentence twice in a row, they exert less effort when they hear the repetition. But the CI listeners invest just as much effort the second time around. It’s tempting to think that this reflects a constant always-alert approach to listening, which might explain the fatigue they experience.

Figure 6. Effort can be aimed at specific key moments in time, or spread to also cover information that you already have.

We are also testing a situation where the listener is told in advance whether a sentence will be easy or hard to understand, but in some cases that clue is missing. When it is missing, the listeners with cochlear implants are more likely to prepare their effort as if they assume the sentence will be hard, which I think teaches us a lot about how they might approach speech communication.

19. Interesting. You mentioned these effortful things, like dwelling on a sentence before moving on to the next one. Can we coach or train our patients to avoid a given strategy in hopes of reducing their effort?

I would first want to understand why they are adopting that strategy. It’s possible (even likely) that if a person with hearing loss has developed a strategy, it’s because that strategy is adaptive for their needs. Who am I to say that their strategy is wrong? Perhaps in some situations it’s better to exert effort to fixate on a word rather than risk making a huge mistake by misunderstanding the talker’s words. The more you talk to people with hearing loss, you pick up stories that they all have about a situation where a simple mistake led to an embarrassing situation. So rather than assuming that they should train to listen the way I do (as a person with typical hearing), I would first want to understand whether they have a good reason for their own strategy.

20. What are some of the things that we still need to learn about listening effort?

- One huge frontier is how to measure effort in the clinic in a quick and reliable way. To do this, we would need a measurement that is stable within an individual across testing sessions (unlike pupil dilation, which can vary quite a bit depending on alertness or time of day).

- We want to learn more about whether effort really is connected with other seemingly related factors such as social isolation, fatigue, and cognitive decline. Ben Hornsby’s team at Vanderbilt is making big strides toward this goal (including the development of a quick clinical fatigue assessment), so I keep an eye on their work.

- We need to identify the right speech listening task to use to assess effort in a relevant way. For example, some common stimuli like single words or digit triplets on their own are not tapping into the kinds of effort that might dominate a person’s experience in conversation where words have to combine form meaningful ideas. People don’t walk around every day repeating what they hear word-by-word, and yet that’s what we have them do in an evaluation. We have to strive to be more creative and realistic.

- We have been stuck in a world of speech repetition, where we track only the words but not the speaker’s intention, emotion, attitude, or identity. These are features of speech that can determine whether conversation is successful. I don’t know yet how they interact with effort, but I suspect that if you misunderstand the tone of someone’s voice, it could cause you to work hard to unwind the misunderstandings. Tapping into these abilities using stimuli that patients care about can help us make important progress.

- A big challenge will be to determine how much effort is the right amount. Recall before how I suggested that “minimal” effort is not the goal. The amount of satisfaction that a person experiences while listening is probably related to how much information or enjoyment they get out of their effort. Björn Hermann and his colleagues have begun looking at this with their measures of listening absorption, and I think this is the right path. When Sarah Hughes interviewed CI patients for her 2018 paper (which you can find in Ear and Hearing), one of the key themes that emerged was the frustration they felt when their effort was wasted. So I think that the quality of the listening experience must involve some estimate of how much satisfaction one seeks and receives, rather than simply how accurate they are at hearing words.

So the bottom line is . . .

Simply, I want to learn how to make patients aware of their own effort and coach them on how to manage it. I want audiologists to take steps to recognize effort to better connect with their patients. We don’t always have the tools to instantly reduce or avoid listening effort, but we can take steps to help a patient to manage effort so that they don’t get overloaded. I believe that if we can do this, we will see improved outcomes with our amplification strategies and other rehabilitative treatment efforts. This can be a big way that we as audiologists add value to the hearing healthcare experience – not just with devices and measurements, but with true understanding that helps a patient expand their listening world.

References

Brons, I., Houben, R., & Dreschler, W. A. (2013). Perceptual effects of noise reduction with respect to personal preference, speech intelligibility, and listening effort. Ear and Hearing, 34(1), 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0b013e31825f299f

Desjardins, J. L. (2016). The effects of hearing aid directional microphone and noise reduction processing on listening effort in older adults with hearing loss. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 27(1), 29–41. https://doi.org/10.3766/jaaa.15030

Fiedler, L., Seifi Ala, T., Graversen, C., Alickovic, E., Lunner, T., & Wendt, D. (2021). Hearing aid noise reduction lowers the sustained listening effort during continuous speech in noise—a combined pupillometry and EEG study. Ear and Hearing, 42(6), 1590–1601. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000001050

Fleming, J., & Winn, M. (2024, October 12). Seeing a talker’s mouth reduces the effort of perceiving speech and repairing perceptual mistakes for listeners with cochlear implants. Preprint available at https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/45f6b

Francis, A. L. (2022). Adding noise is a confounded nuisance. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 152(3), 1375. https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0013874

Francis, A. L., Chen, Y., Medina Lopez, P., & Clougherty, J. E. (2024). Sense of control and noise sensitivity affect frustration from interfering noise. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 156(3), 1746–1756. https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0028634

Gianakas, S. P., Fitzgerald, M. B., & Winn, M. B. (2022). Identifying listeners whose speech intelligibility depends on a quiet extra moment after a sentence. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 65(12), 4852–4865. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_JSLHR-21-00622

Gianakas, S. P., & Winn, M. (2024, March 20). Advance contextual clues alleviate listening effort during sentence repair in listeners with hearing aids. Preprint available at https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/5hfg8

Hornsby, B. W. (2013). The effects of hearing aid use on listening effort and mental fatigue associated with sustained speech processing demands. Ear and Hearing, 34(5), 523–534. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0b013e31828003d8

Hughes, S. E., Hutchings, H. A., Rapport, F. L., McMahon, C. M., & Boisvert, I. (2018). Social connectedness and perceived listening effort in adult cochlear implant users: A grounded theory to establish content validity for a new patient-reported outcome measure. Ear and Hearing, 39(5), 922–934. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000553

Hughes, S. E., Rapport, F., Watkins, A., Boisvert, I., McMahon, C. M., & Hutchings, H. A. (2019). Study protocol for the validation of a new patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) of listening effort in cochlear implantation: The Listening Effort Questionnaire-Cochlear Implant (LEQ-CI). BMJ Open, 9(7), e028881. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028881

Krueger, M., Schulte, M., Brand, T., & Holube, I. (2017). Development of an adaptive scaling method for subjective listening effort. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 141(6), 4680. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.4986938

McRackan, T. R., Hand, B. N., Cochlear Implant Quality of Life Development Consortium, Velozo, C. A., & Dubno, J. R. (2022). Development and implementation of the Cochlear Implant Quality of Life (CIQOL) Functional Staging System. The Laryngoscope, 132(Suppl 12), S1–S13. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.30381

Seitz, J., Loh, K., & Fels, J. (2024). Listening effort in children and adults in classroom noise. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 25200. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-76932-7

Wendt, D., Hietkamp, R. K., & Lunner, T. (2017). Impact of noise and noise reduction on processing effort: A pupillometry study. Ear and Hearing, 38(6), 690–700. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000454

Wendt, D., Koelewijn, T., Książek, P., Kramer, S. E., & Lunner, T. (2018). Toward a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of masker type and signal-to-noise ratio on the pupillary response while performing a speech-in-noise test. Hearing Research, 369, 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2018.05.006

Winn, M. B. (2016). Rapid release from listening effort resulting from semantic context, and effects of spectral degradation and cochlear implants. Trends in Hearing, 20, 2331216516669723. https://doi.org/10.1177/2331216516669723

Winn, M. B. (2024). The effort of repairing a misperceived word can impair perception of following words, especially for listeners with cochlear implants. Ear and Hearing, 45(6), 1527–1541. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000001537

Winn, M. B., & Teece, K. H. (2021). Slower speaking rate reduces listening effort among listeners with cochlear implants. Ear and Hearing, 42(3), 584–595. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000958

Winn, M. B., & Teece, K. H. (2022). Effortful listening despite correct responses: The cost of mental repair in sentence recognition by listeners with cochlear implants. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 65(10), 3966–3980. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_JSLHR-21-00631

Wong, L. L. N., Chen, Y., Wang, Q., & Kuehnel, V. (2018). Efficacy of a hearing aid noise reduction function. Trends in Hearing, 22, 2331216518782839. https://doi.org/10.1177/2331216518782839

Citation

Winn, M. (2025). 20Q: Listening effort – understanding its role in audiology and patients' lives. AudiologyOnline, Article 29239. Available at www.audiologyonline.com