From the Desk of Gus Mueller

From the Desk of Gus Mueller

If you are at all involved with the fitting of hearing aids, you know that over the years we’ve had several different published guidelines regarding how they should be selected and fit. Going back to the 1990s, you’ll find documents from the Vanderbilt/VA Consensus Meeting and the Independent Hearing Aid Fitting Forum (IHAFF). Guidelines also are available from both the AAA and the ASHA. Five years ago, a “standard” for the fitting of hearing aids was published by the Audiology Practice Standards Organization (APSO; read the article here).

What all these documents have in common is the mention of the need for some type of outcome measure, to determine if the intervention (the use of hearing aids) was successful. The IHAFF protocol even included its own outcome measure, the Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB; pronounced “AYE-FAB”), which has gone on to become far more popular than the protocol itself. Like the APHAB, most outcome measures are self-reported; but, depending on the domain of interest, more objective measures, such as speech recognition assessment, also could be used.

There of course are many domains related to the use of hearing aids, and as a result, there is a long list of outcome measures. While most measures focus only on one domain, consider that the IOI-HA (Independent Outcome Inventory—Hearing Aids) has items covering seven different domains (one question for each domain). So many domains. So many outcome measures to choose from. What’s a busy clinician to do?

Never fear, help is here, and from none other than the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). The NASEM was approached by several other professional agencies to examine the state of the science in outcomes research related to interventions in adult hearing healthcare. More specifically, the NASEM was tasked with developing a core set of outcome domains, each with an associated outcome measure. As a result, a committee of experts was formed, and for the past year or more, they have been working on this charge. Their findings have now been published and we have a preview for you here at 20Q.

If you’ve followed the research regarding hearing aid outcome measures, or even if you’re only a casual observer, you’re familiar with the work of audiologist Larry Humes. It’s therefore surprising to no one that Larry was one of the experts selected for the NASEM group, and he’s with us this month to give us the lowdown on the final recommendations.

Larry E. Humes, PhD, is a distinguished professor emeritus in the Department of Speech, Language and Hearing Sciences at Indiana University. He has served as associate editor, editor, and editorial board member for several audiology journals. Larry has received the Honors of the Association and the Alfred Kawana Award for Lifetime Achievement in Publications from the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, the James Jerger Career Award for Research in Audiology, and the Presidential Award from the American Academy of Audiology. He also was selected to present the prestigious Carhart Memorial Lecture at the annual meeting of the American Auditory Society. He is a fellow of the Acoustical Society of America and of the International Collegium on Rehabilitative Audiology (ICRA).

Recall that the NASEM group was charged with selecting specific domains and outcome measures that should be used. They did just that—three of them to be exact. See if you agree with their selections, but don’t be too disappointed if one of your favorites didn’t make the cut!

Gus Mueller, PhD Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller CEU articles at www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: Meaningful Outcome Measures for Hearing Interventions in Adults

Learning Outcomes

After reading this article, professionals will be able to:

- Differentiate between an "outcome domain" and an "outcome measure" as defined by the NASEM report.

- Distinguish between "proximal" and "distal" outcome measures.

- Identify the three specific outcome measures recommended by the NASEM committee to assess the effectiveness of hearing interventions in adults.

Larry Humes, PhD

Larry Humes, PhD1. I saw that you were a part of a recent report on the measurement of meaningful outcomes for hearing health interventions in adults by NASEM. Is that correct, and who or what is “NASEM”?

Yes, I was one of thirteen members of the NASEM committee responsible for that report. NASEM is the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. To quote from their website, “The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine are private, nonprofit institutions that provide expert advice on some of the most pressing challenges facing the nation and world. [NASEM’s]…work helps shape sound policies, inform public opinion, and advance the pursuit of science, engineering, and medicine.”

2. OK. That’s impressive, but how did NASEM get involved in outcome measures for hearing interventions?

Groups often contact NASEM when they desire a professional independent examination of existing evidence about a specific policy question or issue. In this case, leaders at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Defense Health Agency, the Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institute on Aging, and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders asked NASEM to examine the state of the science in outcomes research for interventions in adult hearing health care (excluding surgically placed prosthetic devices), with an emphasis on measures that are meaningful to the individual and clinician.

3. That’s quite a challenge!

Well, it was even more challenging in that the NASEM committee was charged with not just reviewing the available science on meaningful outcomes but with identifying a core set of outcome domains and an associated set of recommended outcome measures. A lot of work was involved over an 18-month period and the freely available report can be found here.

4. Wait, you’re starting to lose me. What do you mean by outcome “domains” and outcome “measures” and what is meant by “core”?

All good questions! First, let me tackle outcome “domain” versus “measure.” This distinction can probably be best explained by considering one of the results from this report. The NASEM committee, for example, identified “understanding speech in complex listening situations” as a meaningful outcome domain based on the evidence available.

5. You mean measuring percent-correct word-recognition scores using the NU-6 or CID W-22 monosyllables in noise, right?

No, but thanks, you’re helping me make my point. That’s an example of a possible outcome measure, percent-correct word-recognition score, not the general domain. For a given meaningful outcome domain, there can be multiple measures, and percent-correct word-recognition score is just one of those possibilities.

6. OK! I get it, I think. The meaningful outcome domain was “understanding of speech in complex listening situations” and the committee recommended using word-recognition scores as outcome measures for this domain. Right?

You’re getting closer, but still not quite there. You understand the difference between an outcome domain and outcome measure, but the measures recommended by the NASEM committee had some additional nuance. After reviewing the research literature in detail, the committee identified two measures for this domain. The first was the Words in Noise (WIN; Wilson, 2003) test and the second was the average score from the three speech-communication scales of the Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB; Cox & Alexander, 1995), which is referred to as the APHAB-global score.

7. Now I understand. One outcome domain, understanding speech in complex listening situations, and two measures of this domain, the WIN and the APHAB-global. Correct?

Yes, that’s correct for that domain.

8. Before we go on, could you tell me a little bit about how the committee suggests these measures be conducted, or wasn’t that part of your group’s charge?

The committee didn’t spend a lot of time discussing how these measures should be obtained as that was felt to be within the scope of professional practice guidelines. Our focus was on what should be measured. Generally, though, the idea was that each outcome measure would be obtained unaided at baseline, prior to intervention, and then again, several weeks later, typically 4-6 weeks after intervention. The difference between the unaided baseline scores and the post-intervention scores represents the benefit from the intervention.

Importantly, of all the recommended outcome measures, only the WIN requires direct involvement of the clinician to administer the test. The APHAB (as well as one other recommended outcome measure--see below), is a self-report measure that can be easily set up on an iPad or other tablet. These could be completed while the individual is waiting in the clinic or online before coming to the clinic. The APHAB is included in the questionnaire module of the widely available Noah software system, and I imagine the other recommended questionnaire (see below) will be made available soon too.

The WIN materials are freely available through the Department of Veterans Affairs or through the NIH Toolbox (https://nihtoolbox.org/test/words-in-noise-test/). For adults, it takes less than 5 minutes to administer the WIN, and for hearing aids, the WIN likely would be administered in sound-field at a conversational level. Because the monosyllables and the competing speech are recorded together on a single track, the WIN would be presented from a single loudspeaker in front of the individual. Again, the details of how and when to obtain these outcome measures were left to those organizations responsible for clinical practice guidelines and were outside the committee’s statement of task.

9. Why did the NASEM committee opt for two measures of this outcome domain?

Another good question! Mindful of the time burden associated with each outcome measure recommended, the committee still thought that two measures of this domain were needed. There were pros and cons associated with each recommended outcome measure. The WIN, for example, is a behavioral measure, typically obtained under controlled conditions, such as in a sound booth in the clinic or laboratory. As a result, it may be more direct and objective than a self-report measure, such as the APHAB-global. On the other hand, the APHAB-global examines speech-communication benefits in several everyday listening environments beyond the sound booth. In addition, there was a fair amount of information available for the APHAB-global that documented improvements following hearing-aid intervention. Finally, research indicated that correlations between these two measures were weak to moderate, suggesting that the most complete evaluation of speech understanding in complex listening situations could be obtained by using both measures.

10. Were there other outcome domains identified by the NASEM committee?

Yes, about a dozen outcome domains were considered in detail by the NASEM committee and these, together with the measures of those domains identified by the committee, are listed in Appendix B of the report. The other meaningful outcome domain identified by the committee for inclusion in the core set was “hearing-related psychosocial health.”

11. I didn’t realize we even had a measure of hearing-related psychosocial health?

We do, but it hasn’t always been described that way in research and clinical literature. The committee noted that the literature consistently identified a variety of hearing-related psychological, social, and emotional problems that were important to adults with hearing difficulties. This has been recognized for several decades and one of the earliest measures to assess such difficulties before and after intervention was the 25-item Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly (HHIE; Ventry & Weinstein, 1982).

12. I think I heard that the HHIE, after all these years, has been revised?

Yes it has. Recent detailed psychometric analyses of the HHIE led to the development of an 18-item Revised Hearing Handicap Inventory (RHHI; Cassarly et al., 2020), and this was the tool recommended by the committee for the measurement of hearing-related psychosocial health as a meaningful outcome measure based on the available evidence.

13. So, were any other outcome domains or measures identified by the committee?

Yes and no. First, getting back to one of your earlier questions, I never defined the notion of “core set” of outcome domains and measures. In this case, “core” refers to a set of outcomes that are meaningful to individuals with hearing loss. In other words, most adults (in this case) care about these outcomes when they seek hearing help. And then there must be a basic set of measures that could and should be completed in the evaluation of hearing interventions by clinicians and researchers to assess these outcomes. Of course, additional domains and measures can be added to this core set.

14. And the core set is . . .?

All outcome assessments of hearing interventions in adults with hearing difficulties should include at least these three measures: (1) the WIN; (2) the APHAB-global; and (3) the RHHI. Three outcome measures were recommended to assess the two outcome domains that were identified as “core” or essential domains by the NASEM committee. It should be noted that the committee also considered consumers engaged in self-care, including those acquiring over-the-counter devices, and advocated for consumers to have readily available options to assess their own outcomes in a standardized way in the future using the same core set of outcome measures.

15. This makes sense to me, but I’m surprised that a measure near and dear to my heart, real-ear assessment of hearing aid output, was not included in the core set of domains or measures. Why not?

The NASEM committee discussions are all confidential, but as you can imagine the committee deliberated about this a lot and the report discusses this at length. In the end, the committee came to consensus that the restoration of audibility was critical to some interventions, such as hearing aids and pharmacologic or biologic treatments, but it was not universally important across all hearing interventions, such as aural rehabilitation or auditory training. Documentation of the restoration of audibility would change across treatments as well. For hearing aids, the real-ear output of the hearing aid is compared to evidence-based targets. Here, the acoustic signal is changed to make it audible. For pharmacologic treatments, the auditory system is changed and improved hearing thresholds best represent restored audibility. In addition, even for hearing aids or pharmacologic treatments, restoration of the audibility of speech and other important everyday sounds was not the desired end result in and of itself. Rather, the desired goal is to improve speech communication and everyday hearing-related function through the intervention. The restoration of audibility is often a necessary first step to accomplishing that goal.

16. OK. I follow and agree that real-ear verification of output is a necessary first step, but I’m a bit confused about why it is not considered an outcome measure. Can you clarify this?

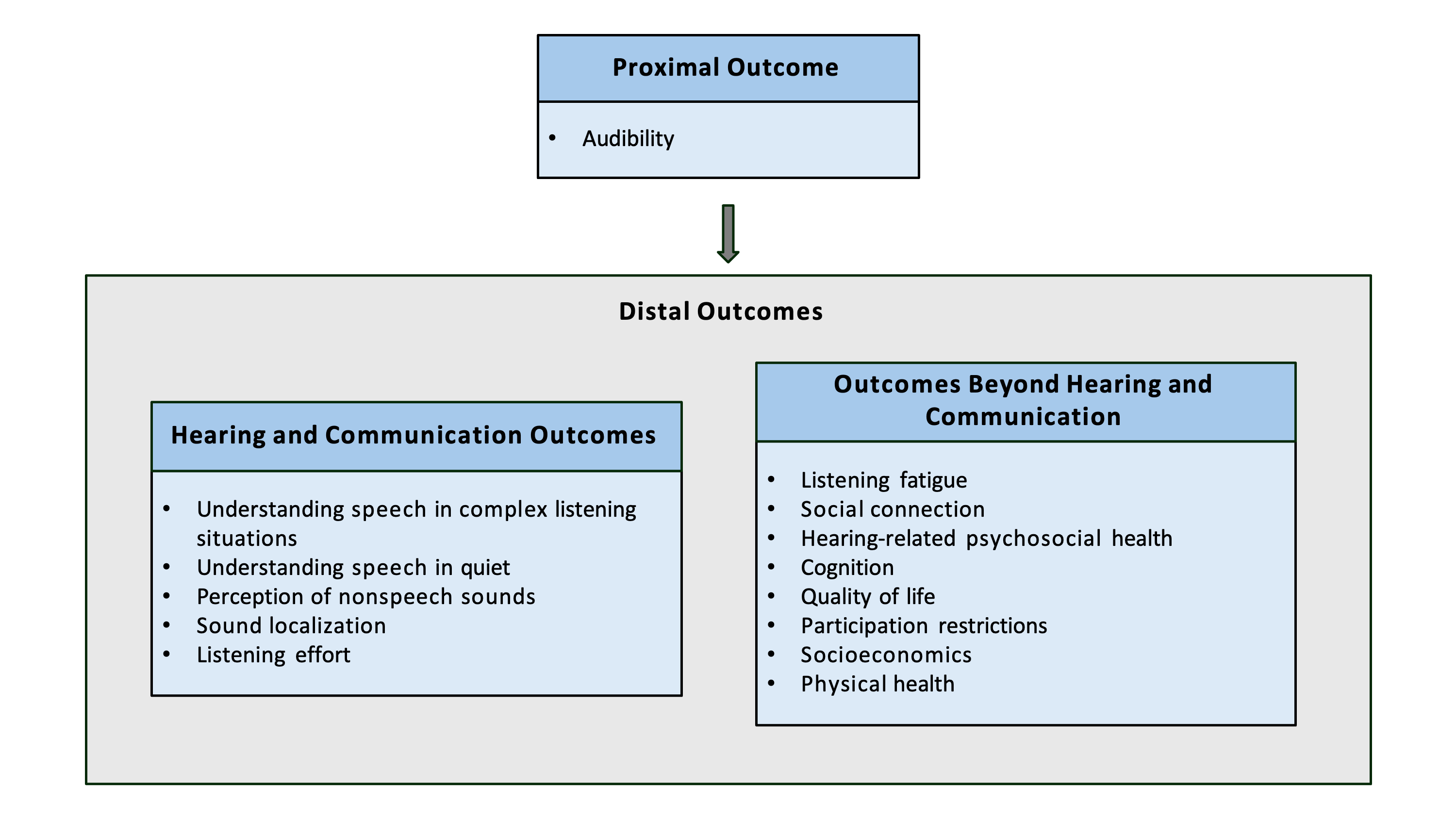

Sure. To explain this, I need to introduce the concepts of “proximal” and “distal” outcomes. The report notes that the restoration of audibility is “a necessary but insufficient” step for the improvement of everyday function. As a result, the restoration of audibility was identified by the committee to be a necessary first step for some interventions, a “proximal outcome”, whereas the core set was focused on meaningful measures of everyday function, “distal outcomes.” Figure 1 (NASEM, 2025; Figure 5-1) from the NASEM report illustrates this concept of proximal and distal outcomes. The box for “Distal Outcomes” lists the wide array of outcome domains considered by the NASEM committee. I’m sure you’ve seen several cases where the output of a hearing aid has matched evidence-based real-ear output targets, a positive proximal outcome, but this has not always been followed by measurable improvements in the understanding of speech in complex listening conditions or in hearing-related psychosocial health, a positive distal outcome.

Figure 1. Relationship between proximal and distal outcomes. Reproduced with permission from the National Academy of Sciences, Courtesy of the National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.

17. Yes, I have. I can follow that thinking. Can we return, though, to the core set of outcome measures? Why was the WIN recommended? It’s not a test commonly used among clinical audiologists.

The NASEM committee considered a wide range of criteria when deciding upon the best outcome measures available to represent an outcome domain. These criteria are provided in detail in Chapter 3 and Appendix C of the report. Briefly, some of the criteria considered included the validity and reliability of the measurement and both have been established for the WIN. In addition, the WIN requires less than 5 minutes to administer and is readily available with no restrictions that would prevent its broad application.

18. You say readily available?

Yes, I think I mentioned this earlier, the WIN is included as the measure of speech-recognition performance in the National Institute of Health’s Toolbox, a freely available iPad-based collection of digital assessments of cognition, motor, sensation and emotion (https://nihtoolbox.org/). Auditory measures, including the WIN, are in the sensation module of the NIH Toolbox (Zecker et al., 2013) and a Spanish version of the WIN has been developed – although more work validating this Spanish version is needed. So, the WIN received high marks for its psychometric development and in terms of its feasibility for broad implementation.

Another criterion considered by the NASEM committee was the “responsiveness” or “sensitivity to change” of the outcome measure. The committee sought evidence showing that the outcome measure was sensitive to change, i.e., demonstrating changes in scores from pre-intervention to post-intervention. Here, there was not much information available as the focus of the WIN historically has been on the assessment of hearing function, not on serving as an outcome measure. It should be noted, however, that the WIN was not alone in having limited evidence supporting its sensitivity to change.

19. That leads me to my next question. I’m pretty sure the most popular speech-in-noise test is the QuickSIN. Why wasn’t it recommended?

Well, the QuickSIN was the other behavioral speech-based outcome measure considered for this domain with, once again, a lot of iterative discussion by the NASEM committee. One of the advantages to the QuickSIN over the WIN is the use of sentences instead of words as the speech signal. And, there are at least some QuickSIN data on its sensitivity to change following hearing-aid intervention. On the other hand, there actually were limited data available at the time of the committee’s deliberations on some basic psychometric characteristics, such as test-retest correlations for the QuickSIN. Appendix D in the NASEM Report provides a very detailed side-by-side comparison of the key psychometric characteristics and other features of the WIN and the QuickSIN.

Ultimately, there was no perfect choice available as a behavioral measure of speech understanding in complex listening situations. The WIN and QuickSIN emerged as the two best available measures among the dozen or so that were considered (see Appendix B of the Report for a full list of measures considered early in our deliberations). In the end, the NASEM committee opted to include the WIN in the core set of outcome measures. Again, this does not preclude clinicians and researchers from also obtaining QuickSIN scores, or any other measures, if so desired.

20. This has all been interesting, but I have to ask . . . how does this impact me and my practice? Does it change what I do on Monday morning?

These are good questions and are a part of the focus of the final chapter of the NASEM report, entitled “Dissemination and Implementation.” To quote from Chapter 7, “…[core outcome sets] can enhance standardization and in turn help improve the usefulness of findings in health care research and clinical assessments to ultimately improve patient outcomes. However, these benefits are only realized if a [core outcome set] is used.” The publication of our conversation represents just one of several steps being taken to disseminate the NASEM Report and, hopefully, to facilitate broad use of the recommended core outcome set. It is hoped that when you return to work Monday morning, you’ll begin to sort out how you might include the WIN, APHAB-global, and RHHI into your routine evaluation of hearing-aid outcomes in your practice. Ultimately, clinicians, researchers, and the individuals with hearing difficulties themselves must use the recommended core set of outcome measures to advance the individual’s and the field’s understanding of the benefits achieved through hearing intervention.

Editor’s Note: As you readers have noticed, on several occasions in this month’s 20Q, Larry has mentioned the NASEM committee, the origin of the findings and recommendations that you have just read about. If you’re like me, this isn’t a process that I’m too familiar with, so I thought it might be meaningful if Larry provided a few more details regarding the working of the committee.

Mueller: You’ve mentioned that this report was the result of many deliberations by the NASEM committee. Who all were on this committee?

Humes: The committee included thirteen individuals with expertise in hearing measurement and management, etiology of and intervention for hearing loss, outcome measurement, primary care, disability and rehabilitation, quality of life, health disparities, public health, and epidemiology. This included practicing audiologists, physicians, scientists, and individuals with hearing loss who had received treatment. Many on the committee will be familiar names to you and to the readership. For a full listing of committee members, please see the published report.

Mueller: Wow…thirteen! That’s a big group!

Humes: That was not even the entire group! Several others were directly involved in the generation of the NASEM committee’s report. In addition to the thirteen committee members, two National Academy of Medicine Fellows, seven NASEM study staff, and one writing consultant made important contributions to the report and kept the committee on task throughout the process.

Humes: The two individuals most responsible for keeping the group on task and seeing this huge undertaking to completion were the committee’s Chair, Theodore G. Ganiats, and the NASEM Study Director, Tracy A. Lustig. Having chaired a similar committee many years ago, I appreciated the challenges faced by this committee and those guiding us through our deliberations so capably from start to finish – a nearly 18-month-long process! I was also impressed with the collegiality of the entire group and their focus on fulfilling the statement of task to the best of our abilities. It was a great group with whom to work!

Mueller: I can’t imagine everyone agreed with the details of the report, its recommendations, and conclusions. Were there serious disagreements? Your secrets are safe with me!

Humes: First, you should know that the work of the committee, deliberations, and communication with the NASEM staff and amongst the committee are all confidential and remain confidential after the report is published. The committee does not discuss the work in progress and does not discuss the specifics of their deliberations, but the committee’s reasoning for their decisions is laid out in the final report. Second, and importantly, prior to the final report, the entire committee comes to consensus on the recommendations of the report.

Mueller: And I suspect you also had input from outside sources?

Humes: Most certainly. Although the deliberations of the committee are confidential, the fact-finding process was thorough, broad and open. The committee included a broad range of experts relevant to the topic. In addition, the committee sought input from other groups of individuals to inform their work. The committee held three public webinars with hearing health care professionals, professional association leaders, and individuals with hearing difficulties who receive hearing health care to learn what outcomes mattered the most to these constituents. Additionally, NASEM posted a Call for Perspectives where individuals with hearing loss and clinicians were asked to comment on desired outcomes related to hearing health care. These responses served as additional evidence in determining what outcomes were most meaningful to patients and therefore should be measured.

Mueller: Sounds pretty thorough, but do you think that it’s still possible that the group missed important areas or portions of the research literature?

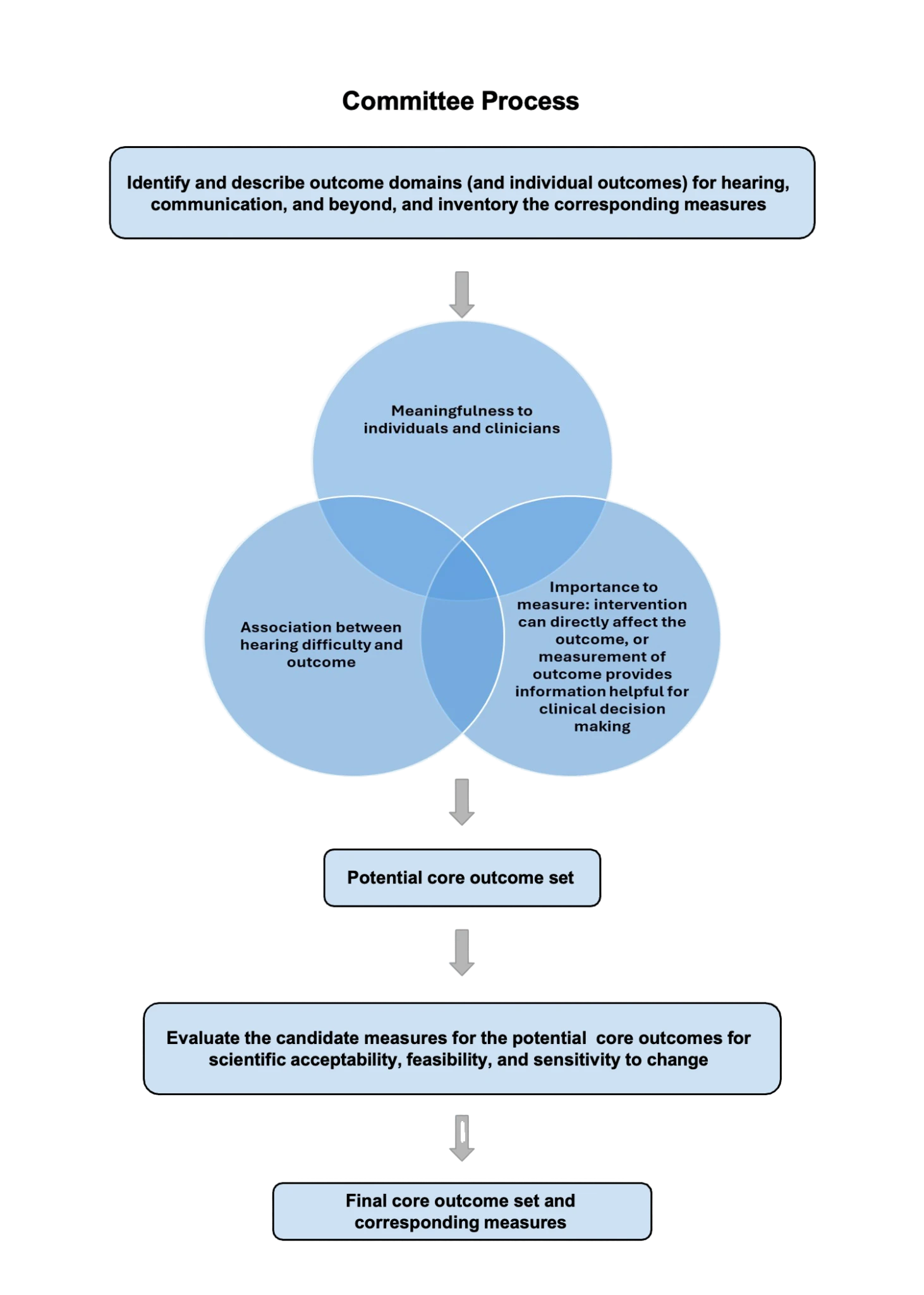

Humes: The report documents the detailed processes that were followed to identify and evaluate outcome domains and outcome measures that were meaningful to adults with hearing difficulties. Figure 2 from the report (NASEM, 2025; Figure 1-1) provides a nice overview of the committee’s process. Ultimately, a core set of such outcome measures having the best available support was recommended.

To more directly answer your question, to ensure the validity and credibility of the NASEM report, an extensive review process was undertaken. In this case, twelve external peer-reviewers not associated with the development of the report provided detailed feedback. Comments and suggested edits from the external reviewers were forwarded to the committee by NASEM staff and final edits were completed based on those reviews.

Figure 2. Flow chart of the process used by the NASEM committee. Reproduced with permission from the National Academy of Sciences, Courtesy of the National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.

Mueller: Really, twelve external reviewers! That’s a lot.

Humes: And there is more. After copy-editing and formatting, the report was released to the sponsors for review. Shortly after the sponsors received the report, the report was released broadly, and a virtual public meeting was held to respond to comments from anyone choosing to attend the virtual meeting. These interactions served to clarify and give context to the process, findings, and recommendations included in the final released report. This also served as the first of many efforts to share the report with the public.

Mueller: Thanks to you and your committee for all the work, and for sharing your findings with us here at 20Q.

References

Audiology Practice Standards Organization (2021). S2.1 Hearing Aid Fitting for Adult & Geriatric Patients. https://www.audiologystandards.org/standards/display.php?id=102

Cassarly, C., Matthews, L. J., Simpson, A. N., and Dubno, J. R. (2020). The revised hearing handicap inventory and screening tool based on psychometric reevaluation of the hearing handicap inventories for the elderly and adults. Ear and Hearing, 41, 95-105.

Cox, R. M. and Alexander, G. C. (1995). The Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit. Ear and Hearing, 16(2), 176–186.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2025). Measuring Meaningful Outcomes for Adult Hearing Health Interventions. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/29104

Ventry, I. M. and Weinstein, B. E. (1982). The Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly: A new tool. Ear and Hearing, 3, 128–134.

Wilson, R. H. (2003). Development of a speech-in-multitalker-babble paradigm to assess word-recognition performance. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 14(9), 453–470.

Zecker, S. G., Hoffman, H. J., Frisina, R., Dubno, J. R., Dhar, S., Wallhagen, M., Kraus, N., Griffith, J. W., Walton, J. P., Eddins, D. A., Newman, C., Victorson, D., Warrier, C. M., and Wilson, R.H. (2013). Audition assessment using the NIH Toolbox. Neurology, 80(11 Suppl 3), S45–48.

Citation

Humes, L. (2025). 20Q: Meaningful outcome measures for hearing interventions in adults. AudiologyOnline, Article 29355. Available at www.audiologyonline.com