Learning Outcomes

After reading this article, professionals will be able to:

- Define auditory ecology and how it applies to hearing aid selection in the clinic.

- Describe the shortcomings associated with speech intelligibility scores for determining hearing aid treatment goals and outcomes.

- Describe how a hearing aid wearer’s unique auditory ecology can be assessed and accounted for during a routine hearing aid evaluation.

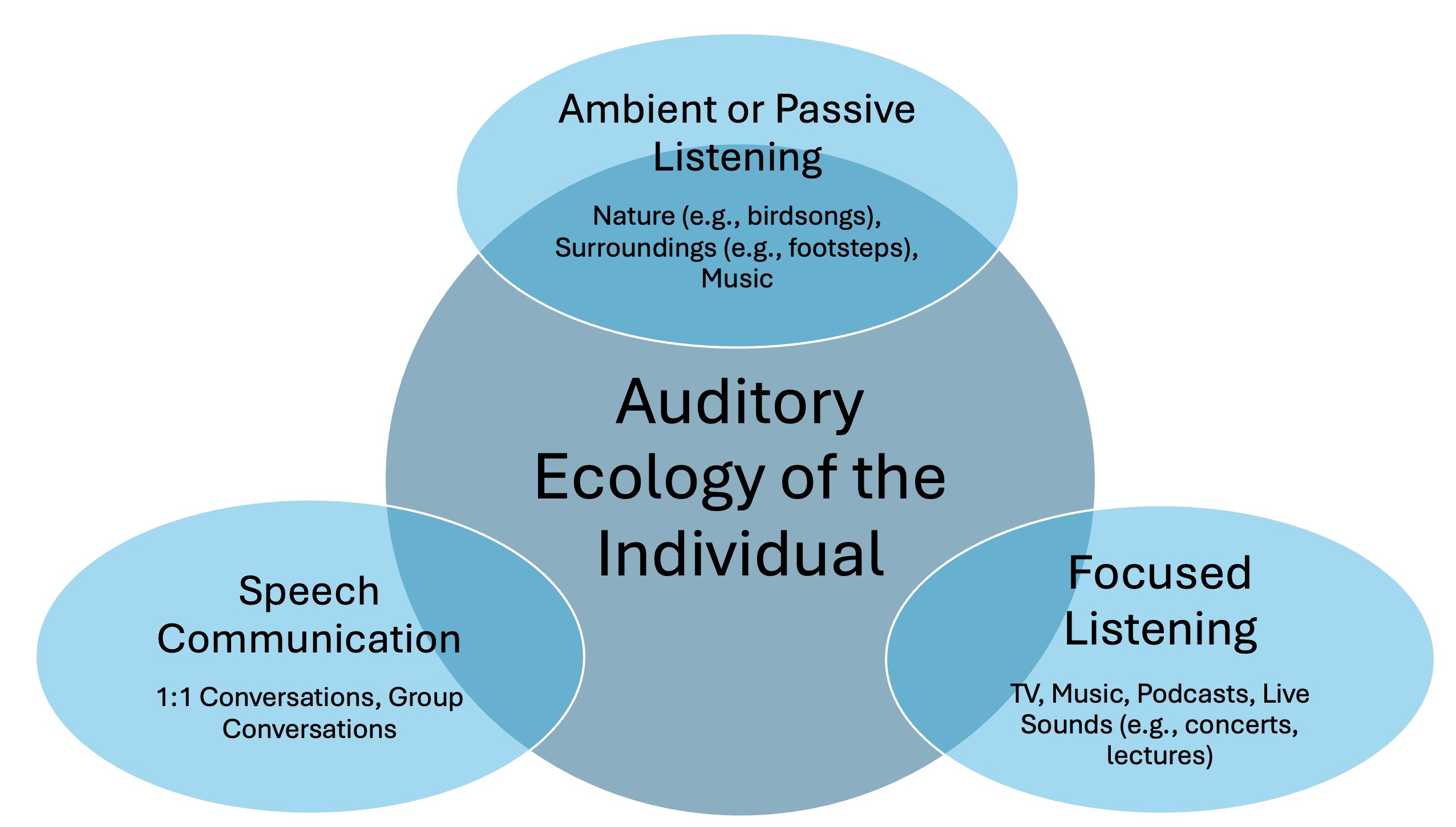

This tutorial provides a working framework for clinicians to better understand and evaluate three broad areas of an individual’s auditory ecology: speech communication (e.g., group conversations), focused listening (e.g., enjoyment of music), and non-specific listening (e.g., relaxation from the sounds of nature) prior to hearing aid use. It also demonstrates how a common challenge related to hearing loss: listening-related fatigue, a problem that can affect all three areas of auditory ecology, can be measured in the clinic, pre- and post-fitting of hearing aids.

Like all help-seekers in your clinic, Margaret, your 11 am patient, has a story to tell. Almost ten years ago, she began noticing her world growing subtly quieter. First, familiar voices at family gatherings blurred into the background, and she sometimes embarrassingly mistook questions for statements -- nodding politely while pretending to understand the gist of the conversation. Then, background sounds she took for granted, ones she oftentimes found relaxing and restorative, like birdsongs and the rustling of leaves, vanished so completely she forgot they even existed. Finally, conversations in noisy environments became especially taxing, as she struggled to follow the swift back and forth of conversations at work. Having to focus so hard during the workday left her too exhausted to participate in end-of-day social activities. After spending just a few minutes with her, it was plain to see that her gradual hearing loss affected more than just her ears; it influenced her mood, disposition, social life, and sense of connection

Welcome to Margaret’s world: A rich, varied, and diverse soundscape, hijacked by hearing loss.

A day in the life of a person with hearing loss, struggling to effectively communicate, is more varied and diverse than many realize. Yet the tools we use in the clinic to help us make hearing aid selection and fitting decisions, namely speech audiometry using single words in quiet and the routine case history/intake interview, are rather limited. Compounding the challenge: Most hearing aid features are designed to optimize speech understanding, even though some patients’ primary goal might be listening to music, receiving maximum listening comfort in noisy places, or enjoying the sounds of nature – listening objectives that often require different signal processing strategies than needed to optimize speech intelligibility. The aim of this tutorial is to provide a rationale and framework that can be used to assess three broad areas of an individual’s auditory ecology: speech communication (e.g., social conversations), focused listening (e.g., music) and non-specific listening (e.g., sounds of nature) prior to hearing aid use, and how an underlying factor, listening-related fatigue, affects all three facets.

We start with the use of speech intelligibility testing and its traditional role in selecting hearing aids.

Speech Intelligibility Testing: Important, But Limited

Speech audiometry, conducted in quiet using single words, is one of the most popular assessment tools used clinically. According to survey data, 100 percent of audiologists routinely use the information from speech reception thresholds, and suprathreshold word recognition in quiet testing as part of their hearing aid fitting process (Anderson et al., 2019). Although these traditional assessment tools have their place, they have significant limitations for several reasons.

First, speech intelligibility tests are useful for estimating auditory function, and they are an essential part of the diagnostic test battery, especially when noise is used (Fitzgerald et al., 2024). However, speech intelligibility tests, even when noise is employed, fail to capture the broader psychosocial, cognitive, and functional consequences of hearing loss. Research shows that hearing loss affects more than just the ability to understand speech—it also impacts listening effort and fatigue (Pichora-Fuller et al., 2016), cognitive load and memory (Peelle & Wingfield, 2016) as well as social participation and emotional well-being (Mick et al., 2014). Consequently, focusing solely on speech intelligibility scores during the assessment overlooks several key domains of hearing aid benefit, including the reduction of listening effort and listening-related fatigue, enjoyment of music or sounds of nature, and the promotion of social engagement.

Second, speech intelligibility measures conducted in the clinic (usually a quiet soundbooth) do not reliably predict real-world hearing aid benefit. Studies from decades ago (Smoorenburg, 1992) as well as systematic reviews (e.g., Taylor, 2007; Davidson et al., 2021) suggest that single-word or sentence tests in quiet before fitting offer, at best, a weak correlation with long-term patient benefit or satisfaction. In one seminal study, for example, Humes (2007) showed that self-reported hearing difficulties and real-world hearing aid outcomes often correlate more strongly with subjective assessments (e.g., questionnaires like the Hearing Handicap Inventory-Adults (HHIA)) than with word recognition scores. The poor predictive value of speech intelligibility scores is likely twofold: 1.) Clinical intelligibility tests are weak proxies for how people perceive benefit or satisfaction with hearing aids in everyday listening environments; and 2.) Everyday listening involves complex acoustic environments, such as multi-talker settings, reverberant rooms, and a cacophony of ambient sounds, which are not adequately captured by traditional speech intelligibility measures.

Ceiling effects and individual variability also limit the value of speech intelligibility tests for selecting and fitting hearing aids. For example, at typical conversational levels (e.g., 65 dB SPL), some people may perform near-perfectly, even with significant peripheral hearing loss. Additionally, individuals with moderate or severe hearing loss show considerable divergence between unaided speech recognition and aided performance, making them problematic for use in the hearing aid selection process. Speech intelligibility in quiet also depends on cognitive factors—such as working memory or listening effort—which speech testing does not measure, further limiting its predictive value for fitting success (Salvago et al., 2024).

Finally, and most relevant to this tutorial, speech intelligibility measures lack ecological validity and underrepresent non-speech listening needs, which could be of vital importance to the patient. Quiet, single-listener settings -- by far the most popular method of speech audiometry is conducted -- often don’t reflect daily listening environments. Consequently, traditional speech intelligibility test results fail to capture performance in noise, where most individuals with hearing loss struggle (Hey et al., 2023). Further, many hearing aid patients frequently report that non-speech sounds are integral to their daily experience and quality of life (Moore, 2016). A singular focus on speech intelligibility does not adequately address these needs. By focusing too much attention on speech intelligibility, clinical assessments may ignore other critical listening needs, such as music appreciation, environmental sound awareness, spatial hearing, or localization, as well as the positive emotions associated with improving each of these.

A more holistic, patient-centered approach—one incorporating subjective self-reports and in-depth dialogue with the patient about their real-world listening intentions combined with properly conducted speech in noise testing—is necessary for determining hearing aid candidacy and ensuring optimal patient outcomes.

Optimizing Aided Speech Intelligibility: Critical, But Not the Whole Story

It is well-established that the default signal processing algorithm of most hearing aids is intended to optimize speech intelligibility. And for good reason: improved speech intelligibility remains the number one goal of most hearing aid wearers (Dobson 2025). Further, there is an abundance of evidence demonstrating that when effective aided audibility is achieved, speech intelligibility is optimized. (See Appendix 1 for a review of this evidence). Regardless of the manufacturer’s specific first-fit starting point, in which there are substantial gain and output differences across brands, the primary goal of any manufacturer’s default algorithm is to repackage sounds into the residual dynamic range of the patient so that speech intelligibility is improved. Several studies (e.g., Moore & Sek, 2019; Alexander, 2021), however, have indicated that parameters such as compression ratios and kneepoints, directionality, and noise reduction, intended to optimize speech intelligibility, are less effective for improving listening comfort, listening to music, or hearing important environmental sounds. Some patients may prioritize these benefits more than improved speech intelligibility.

Although optimizing aided speech intelligibility remains a high priority, it is not the only goal. By focusing too much attention on improving speech intelligibility at the expense of other listening needs, clinicians could inadvertently create one or more of the following problems: A.) A delay or non-use of hearing aids for individuals with “good” speech scores but real-world communication difficulties that are unrelated to understanding speech. B.) Overfitting devices default to a first-fit algorithm in which only optimizing speech intelligibility is considered, rather than broader, more holistic listening needs. C.) Reinforce stigma by implying that hearing aids are only for those with significant hearing loss on the audiogram or with “poor” speech intelligibility deficits.

This overreliance on optimizing speech intelligibility at the expense of other factors could be especially problematic for those with diverse listening demands that are not associated with prioritizing speech understanding ability. Several studies indicate the typical hearing aid wearer’s listening experiences are rich, varied, and diverse – in a word: individualized. One study of 128 older adults (average age ~69 years) who wore hearing aids for approximately 6 weeks revealed three distinct environmental usage profiles. Their datalogging analysis showed the hearing aids were worn in a quiet setting ~35% of the time, in a situation where speech was present ~41% of the time, and in a noisy setting ~24% of the time (Humes et al., 2018). Improved speech intelligibility, undoubtedly, was not the only goal of patients in these listening situations.

Entropy, a term that describes randomness across listening situations, has also been used in the analysis of aided listening environments. In one study (Jorgensen et al., 2023) involving participants from four groups (younger listeners with normal hearing and older listeners with hearing loss, each group from either an urban or rural area), ecological momentary assessments (EMA) were taken from the participants’ hearing aids for one week. (See Appendix 2 for more on EMA). Entropy values based on sound pressure levels, environment classifications, and ecological momentary assessment responses were calculated for each participant to quantify the diversity of auditory environments encountered over the course of a week. Although the results showed that younger listeners encounter a greater diversity of auditory environments (higher entropy) than older listeners, there was substantial individual variability.

Additionally, Jorgensen et al (2023) used EMA to identify the type of activities the four groups of hearing aid wearers engaged in. They found that approximately 25% of the EMA participants' snapshots involved active listening. The researchers also measured the distribution of listening situations for all four groups; most listening situations were comprised of live conversation or passive listening to media (e.g., TV watching). Again, it is safe to assume that speech intelligibility was not the only improvement sought by patients in these situations.

Other studies demonstrate that many hearing aid wearers spend considerable time listening in quieter environments where speech intelligibility may not be a priority. For example, Klein et al. (2018) found that older adults spent 12% of their time in situations where meaningful speech was present, while 40% of their time was spent in quiet situations where they tended to be passive listeners, not focused on understanding speech.

A growing body of evidence also indicates that non-speech, often quieter, listening situations are beneficial for many individuals with hearing loss. As Lelic et al. (2025) recently noted, a person’s ability to monitor or enjoy their surroundings, particularly sounds of nature, is important for their well-being, and the inability of persons with hearing loss to hear these natural sounds may be underappreciated by clinicians.

Another recent study demonstrated that the sounds of nature are important to most people with hearing loss – even though these sounds may have been inaudible for several years. Apoux et al. (2025) aimed to understand how hearing loss and hearing aid use affect the perception of natural sounds—such as birdsongs, wind, rain, and other environmental acoustic cues—and their importance in daily life, from the perspective of hearing care professionals. They conducted an online survey of 301 hearing care professionals in France, who were asked to rate patients’ perception of natural sounds before and after hearing aid use. The survey respondents reported that patients experienced a significant increase in the ability to hear natural sounds after wearing hearing aids for a few weeks. This increase was especially pronounced among patients from remote rural areas, where it is widely believed that such sounds may have a greater presence. Further, the respondents observed improvements in how accurately and pleasantly patients listened to natural sounds.

Apoux et al. (2025) also noted that patients, too, rated the importance of natural sounds more highly post-fitting. Their work shows that patients value listening to natural sounds and are satisfied with the performance of their hearing aids in these listening situations. Given its significance for well-being and cognitive health, clinicians are encouraged to expand their focus beyond speech intelligibility to include environmental and natural sound perception (Lelic et al., 2025).

Besides the importance of natural and environmental sounds, listening to music is another important listening experience for many individuals with hearing loss. The ability to listen to and enjoy music would seem to be taking on added importance now that virtually all modern hearing aids allow wireless Bluetooth streaming when used in combination with a smartphone.

It is well-documented that hearing loss negatively impacts the enjoyment of music (Bleckly et al., 2024). In a cross-sectional study, Chern et al (2023) assessed the effects of hearing loss on the enjoyment of music on 100 adult hearing aid wearers and a control group of normal hearing individuals. Participants listened to musical excerpts and rated three aspects—pleasantness, musicality, and naturalness—on visual analog scales, both with and without their hearing aids. The normal-hearing controls reported significantly higher music enjoyment across all measures compared to the hearing aid wearers. They also found that individuals with greater degrees of hearing loss (higher pure tone averages) had significantly lower scores across all three enjoyment measures (pleasantness, musicality, naturalness).

Additionally, recent systematic reviews support music’s healing and restorative potential across a variety of contexts: reducing stress (de Witte et al., 2020) alleviating pain (Chen et al., 2025) and depressive symptoms (Lin & Li, 2025), supporting neurological conditions like Parkinson’s disease, enhancing spiritual and emotional well-being in palliative care (Huda, et al 2023), and improving overall quality of life.

Given that music, for many, is a cornerstone of a happy and meaningful life, as well as ample evidence to suggest it has many restorative effects, clinicians play an important role in ensuring that hearing aid technology (e.g., direct Bluetooth streaming or a dedicated music program) optimizes the sound quality of music. Unfortunately, a recent survey suggests that only ~40% of hearing aid wearers reported that quality of life or restoration effects of music were discussed as a goal of hearing aid use. Less than one-third of those same respondents reported that they were given a dedicated music program in their hearing aids (Oldenberg Hearing & Health Workshop, 2022).

All told, optimizing hearing aid performance for music and environmental sounds is often an important yet unrealized goal of hearing aid use – individualized goals that often lie beyond improving speech intelligibility. Consequently, this requires clinicians to take a broader view of the individual’s auditory ecology.

Auditory Ecology – Expanding Our View of Listening Lifestyle

The late Stuart Gatehouse introduced the term “auditory ecology” to describe a listener’s acoustic environments, the listener’s intentions and tasks they perform within each environment, as well as how those environments influence listening behavior, daily communication, and the overall well-being of the person, as well as its impact on hearing aid design. He showed that factors like how frequently environments change, noise characteristics, spatial arrangement, and an individual’s listening demands shape hearing-aid outcomes, beyond what speech intelligibility scores alone can tell us about the communication needs of the individual. Much of this work went into the development of the Speech, Spatial, and Qualities of Hearing Scale (SSQ) questionnaire, a self-report used to more broadly assess hearing abilities in everyday situations (Noble et al., 2013). A shorter, clinic-friendly version, the SSQ-12, can be downloaded here.

In addition to the SSQ-12, the Auditory Lifestyle and Demand questionnaire (ALDQ) was developed (Gatehouse et al., 1999). The ALDQ is comprised of 24 listening situations that patients are asked to rate on frequency of occurrence and importance of the situation. Given its length, inconsistent phrasing of questions, and questionable construct validity, the ALDQ may not be sensitive to real-world auditory lifestyle and demand (Jorgensen et al., 2023). More recently, Lelic et al (2022) created the Hearing-Related Lifestyle Questionnaire (HEARLI-Q), a 23-item questionnaire that assesses the listening demands and listening lifestyle of individuals with hearing loss. The HEARLI-Q, in its current form, is intended for research rather than clinical use.

Presently, validated clinical tools for assessing the auditory lifestyles of hearing aid wearers, which would help clinicians better understand the listening priorities of each person prior to recommending and fitting hearing aids, are not available. Consequently, clinicians would be wise to adopt a more systematic approach to assessing the individual’s auditory ecology during the case history. Rather than simply asking the help-seeker where they would like to hear better, a more holistic approach warrants questions about what and why the individual wants to accomplish in each situation.

The COSI: More Than Simply Targeting Listening Situations

One of the most popular tools used in the clinic to target goals associated with hearing aid use is the Client-Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI), developed by Dillon et al (1997) and recently updated to COSI 2.0 (Young, 2024). What makes COSI such an effective clinical tool is its open-endedness. Unlike other self-reports, which use a pre-determined list of situations in their assessment process, the COSI requires the clinician and patient to create a tailored list. Another key feature of the COSI is that the patient and clinician work together to target up to five listening situations to be improved with amplification.

Although the COSI remains popular, a recent NAL analysis (Young, 2024) found that many clinicians’ usage of it has drifted from the original guidelines created by Dillon et al. (1997). Their analysis found that clinicians have created their own ways of establishing patient goals and that the patient’s role in the goal-setting process is not well defined. Along those same lines, many clinicians who use the COSI to establish goals have a singular focus on targeting the patient’s listening situations. By focusing only on the listening situation, it is believed that the specific listening intention or purpose of the patient may not be adequately captured. This observation is supported by Dreschler et al. (2016), who showed the COSI could be used to effectively target a broader range of goals (e.g., listening effort or fatigue).

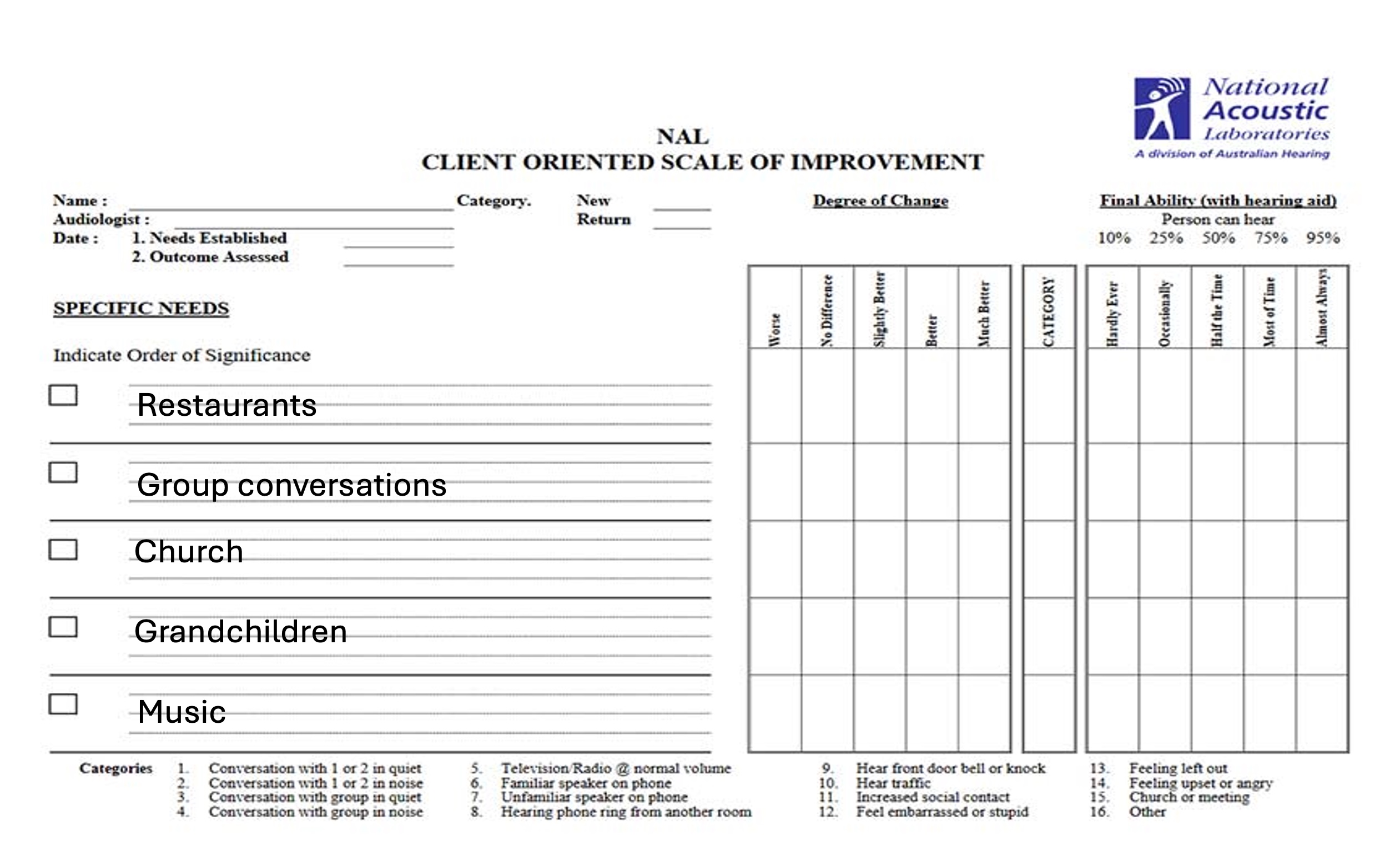

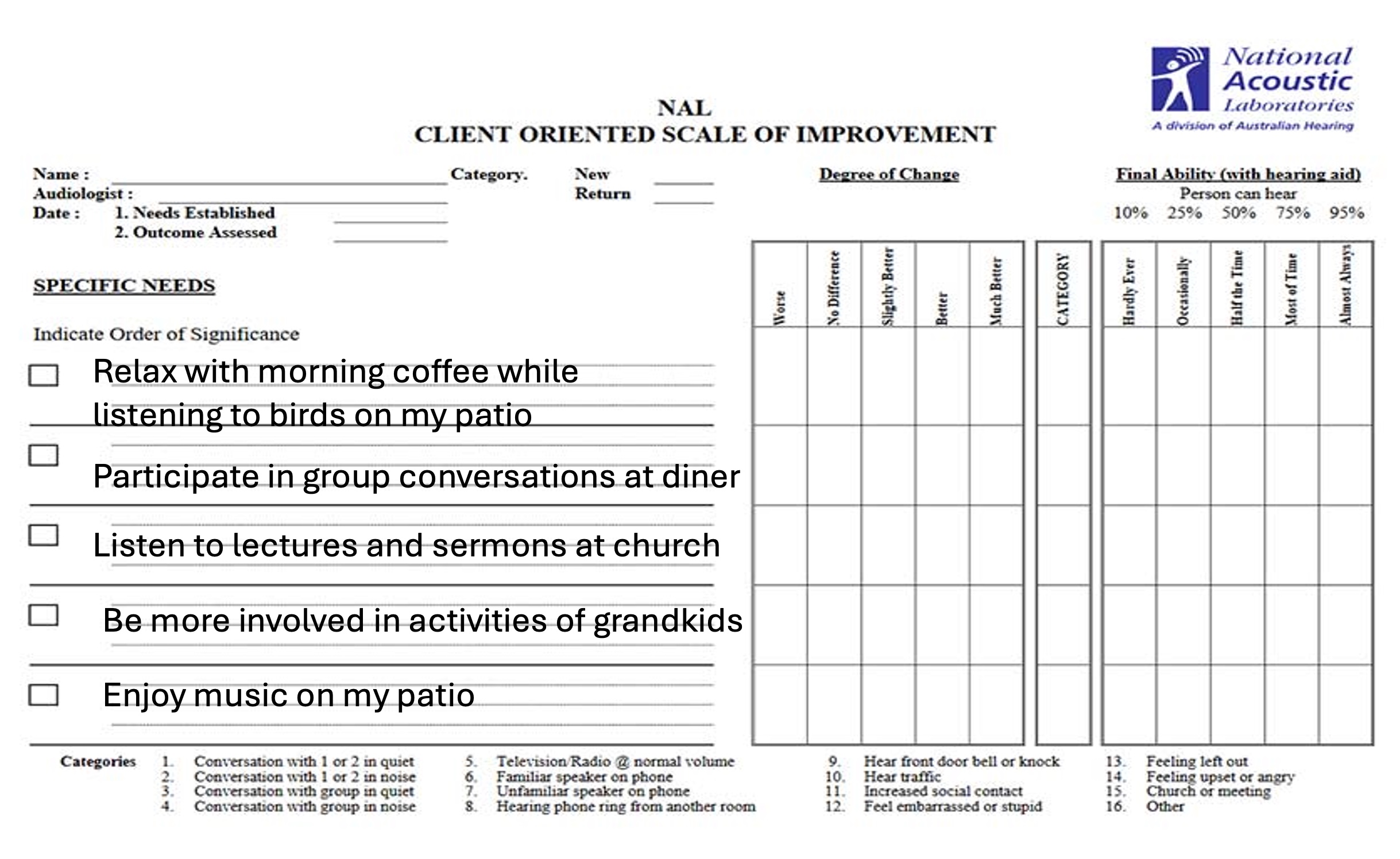

During the goal-setting process, clinicians often target a specific listening situation, say a restaurant or family dinner, but simply listing that situation on the COSI does not fully capture the intention or goal of the patient. Figures 1a and 1b contrast two completed versions of the COSI for one patient. The top (Figure 1a) shows a COSI as it is completed in many clinics with a singular focus on listening situations, while the lower version on the bottom (Figure 1b) shows a completed COSI with an emphasis on the patient’s intentions in each targeted listening situation.

Figure 1a. The COSI is commonly completed in the clinic with a singular focus on the patient’s listening situations that have been targeted for improvement.

Figure 1b. The completed COSI with an emphasis on the patient’s listening intentions.

Assessing the Individual's Auditory Ecology in the Clinic

As Wolters et al. (2016) in their development of Common Sound Scenarios (CoSS), a structured approach for categorizing everyday listening situations in hearing aid research, stated, “use of the term listening situation implies an active listener to a targeted sound. However, a person can solve different tasks in the same acoustical environments that are of a more passive nature” (p. 532). The researchers used this rationale to create Common Sound Scenarios (CoSS), a set of 14 common listening scenarios experienced in everyday life that have been used in research but not clinically.

Using the CoSS as a framework, clinicians can assess auditory ecology more broadly without adding precious time to the communication assessment appointment. This process starts with the intake interview or case history. Because no validated clinical tool exists that assesses auditory lifestyle, and EMA is cumbersome to use in a clinical setting, clinicians must rely on their interpersonal interviewing skills to assess the auditory ecology or lifestyle of the individual.

As illustrated in Figure 2, and drawing from the CoSS framework, there are three broad categories that comprise the individual’s auditory ecology. Broadly, each of the three categories represents a possible listening goal of the individual. You can think of the "listener's intent" as the purpose or goal of the individual when engaging with an auditory input or listening situation. It encompasses the cognitive and attentional focus a person applies to make sense of what they are hearing, based on what they expect or want to hear. It is more than simply the place where an individual seeks improvement; rather, it is what she wants to hear, or how she wants to listen to it.

Figure 2. Three broad categories of an individual’s auditory ecology, with examples of each.

It is likely that most patients prioritize their ability to hear well in these three broad categories, as summarized below. Notes for each of the category examples are provided.

Speech Communication. Examples include group conversations and two people having a conversation. Participation (talking and listening) is a key feature.

Focused Listening. Examples include lectures, concerts, music, and podcasts, sometimes through a media device. Listening with attention to detail is a key feature.

Passive or Ambient Listening. Examples include the sounds of nature (e.g., birdsongs) and sounds that keep people in touch with their environment (e.g., footsteps), sometimes through a media device. Listening while involved in another activity is a key feature.

Rather than focus solely on the listening situations that are problematic to the patient, clinicians are encouraged to steer the goal-setting conversation toward the patient’s priorities in each of these three general listening categories.

To better understand the listening intentions of the patient, a list of questions clinicians can ask that address each of the three categories is provided. Clinicians can ask the following questions during the intake interview or case history.

Speech Communication

Describe some of the interactions (family, friends, work, social) where you want to communicate more effectively.

Who are some of the most important people you want to hear and connect with on a daily or weekly basis?

On a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being “I understand nothing” and 10 being “I understand everything,” how well do you follow the conversations with these individuals?

Passive or Ambient Listening

Do you find certain sounds to be relaxing, soothing, or enjoyable? What are those sounds?

Over the past several years, are there any sounds that you have found relaxing or enjoyable that you miss since you noticed a change in your hearing? Describe those sounds.

What sounds might you be missing that help you to be in better touch with your environment? Or sounds that you find relaxing, or that improve your mood?

Focused Listening

Describe some of the places or events where you need to listen with a great deal of attention or focus. (Examples might include music, theatre, meetings.)

Describe situations where you avoid participating because it feels too exhausting or you get too tired trying to follow along.

On a 1 to 10 scale…. At the end of the day, how much effort do you feel it takes to listen and keep up in these situations? 1 = minimum effort, 10 = maximum effort.

Measuring Listening-Related Fatigue in the Clinic

Beyond speech intelligibility considerations, listening effort, which can lead to listening-related fatigue, should also be a focus during routine clinical assessments. Listening-related fatigue is the mental and physical exhaustion that results from sustained effortful listening, especially in challenging listening situations with adverse signal-to-noise ratios.

The effects of listening effort (Winn, 2025) and listening-related fatigue (Holman et al., 2021) on individuals with hearing loss are well-documented. Bennett et al. (2022) reported fatigue was the third most experienced emotional distress associated with hearing loss, surpassed only by social overwhelm and frustration. More precisely, listening-related fatigue is associated with sustaining effort and attention during a listening task (Hornsby et al., 2021). It is linked to being less productive at work, more prone to accidents, more socially isolated, and more likely to be depressed (Davis et al., 2021). Further, it is possible that fatigued listeners may begin avoiding complex auditory settings like social gatherings, restaurants, or group meetings. Listeners may limit or withdraw from conversations or auditory tasks requiring focus, all integral parts of many individuals’ auditory ecology.

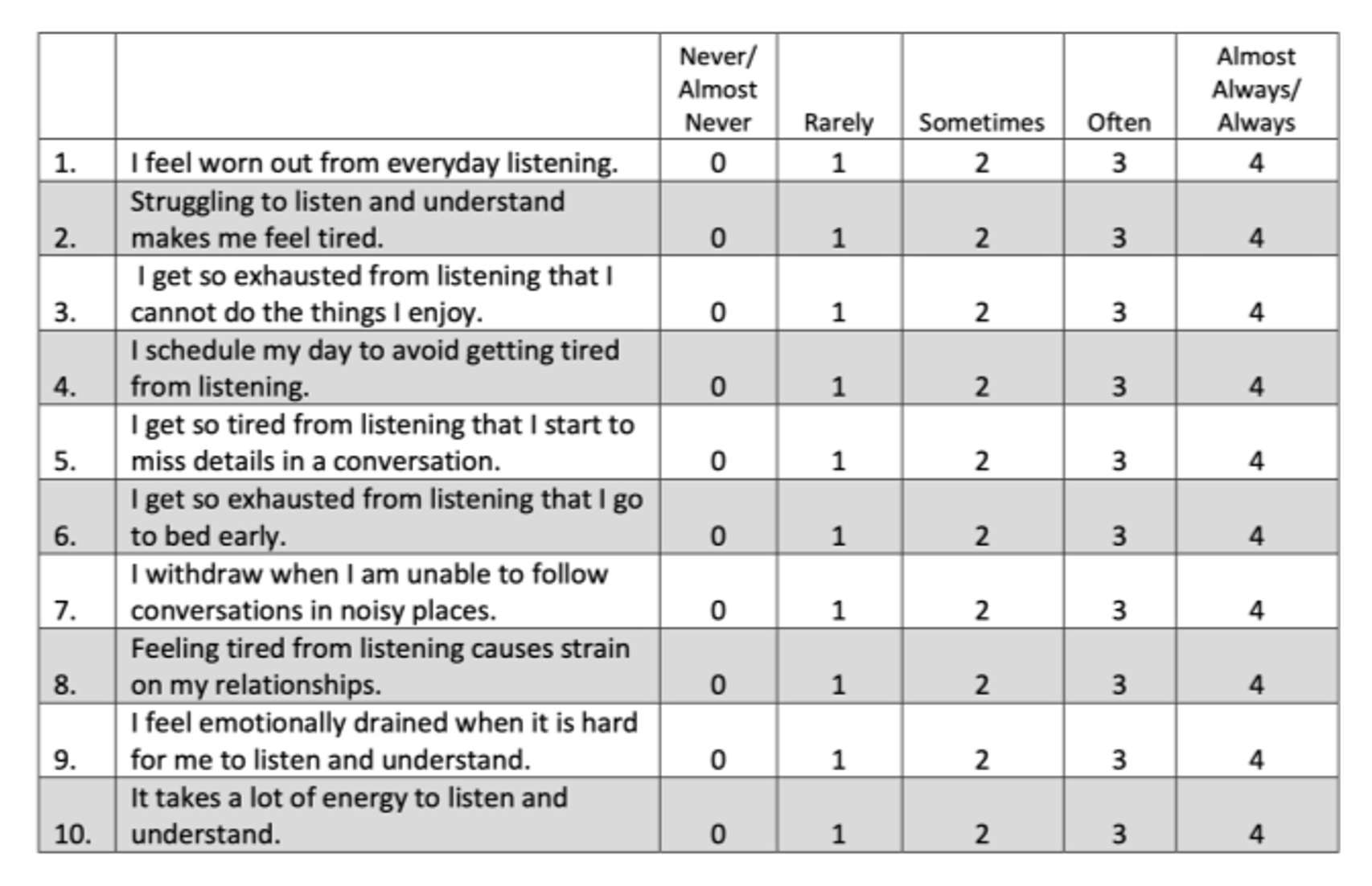

A short version of the Vanderbilt Fatigue Scale for Adults (VFS-A-40), containing 10 items (VFS-A-10), was created by Hornsby et al (2023) to assess listening-related fatigue in the clinic. To better understand the relationship of hearing aid use on measures of listening-related fatigue using the VFS-A10, we investigated a group of hearing aid wearers fitted in a commercial hearing aid dispensing clinic. Thirty-five adults ranging in age from 57 to 90 years old (mean age = 74.1 years) with bilateral, symmetrical, medically uncomplicated hearing loss were fitted with premium and mid-level hearing aids (Signia IX) and followed over a 6-month timeframe. All 35 participants were fitted using standard clinical protocols, including the use of validated prescription gain targets, the use of REM to verify a close match to targets, as well as standard counseling and orientation procedures. (see Taghvaei & Taylor, 2025, for details).

The objective of this study was to answer the following questions:

• Does listening-related fatigue improve with hearing aid use at 1-month post-fitting?

• If so, are listening-related fatigue improvements maintained at 6 months post-fitting?

We administered the VFS-A-10 to the 35 participants during their first-fit appointment, prior to hearing aid use. It was re-administered at approximately 1 month and again at 6 months post-fitting. Figure 3 illustrates the VFS-A-10, which is scored by summing the responses from the five-point Likert scale.

Figure 3. The short version of Vanderbilt Fatigue Scale for Adults (VFS-A-10).

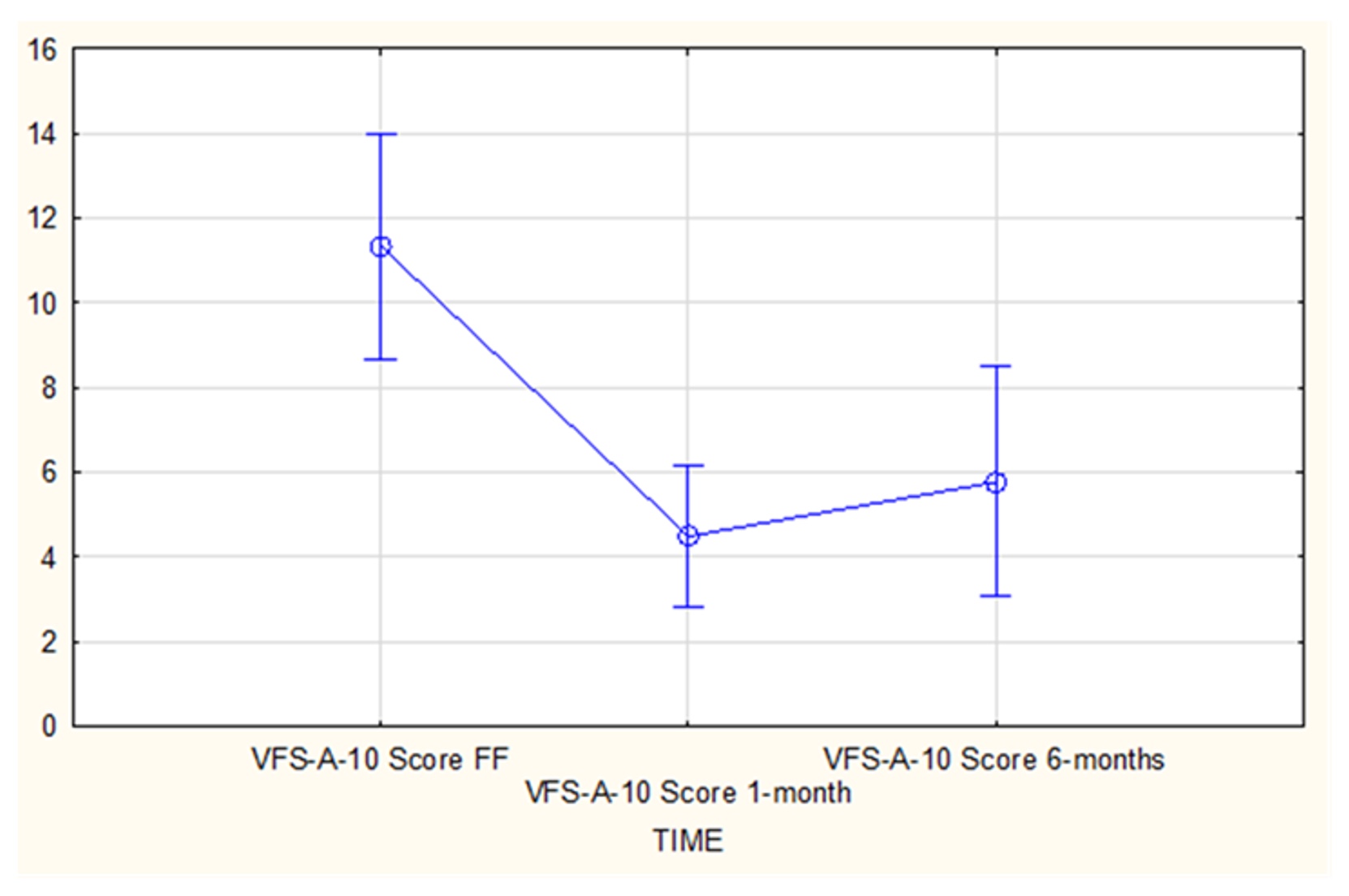

A repeated measures ANOVA with time (first-fit, 1-month post-fit, 6-month post-fit) as the independent variable was conducted. It showed a significant effect of time, with post-hoc tests showing significant differences between first-fit and 1-month post-fit and between first-fit and 6-month post-fit, but no significant difference between 1-month and 6-month post-fit. These results are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Mean scores for VFS-A-10 at first-fit (FF), 1-month post-fitting, and 6-month post-fitting. (Vertical bars denote 0.95 confidence intervals. Vertical axis is the VFS-A-10 score.

Results suggested that for adults with bilateral, symmetrical, medically uncomplicated hearing loss, listening-related fatigue, as measured with the VFS-A-10, is often reduced with hearing aid use. These results demonstrate that listening-related fatigue is reduced with hearing aid use at 1-month post-fitting, and this reduction in listening-related fatigue is maintained at 6-month post-fitting. Given these findings, the VFS-A-10, as a measurement of listening-related fatigue, might be a valuable component of the self-assessment of hearing aid benefit and should be a routine component of the hearing aid fitting and follow-up process.

Conclusion

The objective of this tutorial is to encourage clinicians to think more broadly about the auditory ecology of the individual, and to acknowledge that successful interventions often require more than selecting and fitting hearing aids that are designed to optimize speech intelligibility.

Speech intelligibility in noise testing should remain a cornerstone of the hearing aid selection process, as recently noted by a 2025 NASEM report dedicated to identifying meaningful patient outcomes. The Quick Speech in Noise (SIN) test scores are also more sensitive to perceived auditory disability than traditional speech in quiet test scores or degree of hearing loss (Fitzgerald et al., 2024). To be clear, the message here is not to abandon speech in noise testing. It remains a critical part of the hearing aid selection and fitting process. Clinicians should, however, take a broader view of the person’s daily listening demands (i.e., auditory ecology). During the case history, for example, the clinician should focus on the three areas outlined in Figure 2 and use the COSI to establish more holistic goals focused on the individual’s listening intentions. Rather than view an individual’s listening demands and auditory ecology on the continuum of active to calm, audiologists are encouraged to discuss the triad of speech communication, ambient/passive listening, and focused listening, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Some patients may prioritize focused listening or passive listening, which often necessitates different signal processing strategies than are needed to improve speech intelligibility. Although optimizing speech intelligibility should remain a foundational goal of all fittings, it is important to acknowledge that some patients may benefit from signal processing strategies that enhance music or the sounds or nature. These potential benefits might come from the addition of a second program to the hearing aid or the recommendation of another hearing aid brand that might better align with the listening priorities of the patient.

In many situations, adding a second manual program to the hearing aid is not feasible. Additionally, automatic programs often provide similar underlying processing for music and environmental sounds as they do for their default setting, which is employed to optimize speech intelligibility (e.g., Sangren & Alexander, 2023). Therefore, clinicians should consider a dual-brand strategy when selecting hearing aids. One brand could be selected for those who prioritize speech communication and where noise suppression is essential. A second brand could then be selected for those who prioritize focused and passive listening, in which all sounds are desired to be amplified, and loudness is normalized across the wearer’s acoustic spectrum.

By moving beyond narrow clinical metrics and embracing a fuller picture of auditory ecology, clinicians can better align hearing aid processing strategies with what truly matters to individuals—like Margaret. When we understand not just how someone hears, but how and where they listen, we move closer to restoring not just speech intelligibility, but connection, enjoyment, relaxation, and overall quality of life.

References

Alexander, J. M. (2021). Hearing aid technology to improve speech intelligibility in noise. Seminars in Hearing, 42(3), 175–185. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1735174

Anderson, M. C., Arehart, K. H., & Souza, P. E. (2018). Survey of current practice in the fitting and fine-tuning of common signal-processing features in hearing aids for adults. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 29(2), 118–124.

Apoux, F., Laurent, S., Gallego, S., Lelic, D., Moore, B. C. J., & Lorenzi, C. (2025). Effects of hearing loss and hearing aids on the perception of natural sounds and soundscapes: A survey of hearing care professional opinions. American Journal of Audiology, 34(2), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1044/2025_AJA-24-00171

Bennett, R. J., Saulsman, L., Eikelboom, R. H., & Olaithe, M. (2022). Coping with the social challenges and emotional distress associated with hearing loss: A qualitative investigation using Leventhal's self-regulation theory. International Journal of Audiology, 61(5), 353–364.

Bleckly, F., Lo, C. Y., Rapport, F., & Clay-Williams, R. (2024). Music perception, appreciation, and participation in postlingually deafened adults and cochlear implant users: A systematic literature review. Trends in Hearing, 28. https://doi.org/10.1177/23312165241287391

Chen, S., Yuan, Q., Wang, C., Li, S., Liang, Y., Zhang, W., Wang, S., Wei, Y., & Dong, F. (2025). The effect of music therapy for patients with chronic pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychology, 13, Article 455. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-02643-x

Chern, A., Denham, M. W., Leiderman, A. S., Sladen, D. P., Zaid, I., Le, N., Viver, S. M., Patel, A. A., & Blevins, N. H. (2023). The association of hearing loss with active music enjoyment in hearing aid users. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 169(6), 1590–1596. https://doi.org/10.1002/ohn.473

Davidson, A., Musiek, F., Fisher, J. M., & Marrone, N. (2021). Investigating the role of auditory processing abilities in long-term self-reported hearing aid outcomes among adults age 60+ years. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 32(7), 405–419. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1731007

Davis, H., Schlundt, D., Bonnet, K., Camara, S., Bess, F. H., & Hornsby, B. W. (2021). Understanding listening-related fatigue: Perspectives of adults with hearing loss. International Journal of Audiology, 60, 458–468.

de Witte, M., Spruit, A., van Hooren, S., Moonen, X., & Stams, G. J. (2020). Effects of music interventions on stress-related outcomes: A systematic review and two meta-analyses. Health Psychology Review, 14(2), 294–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2019.1627897

Dillon, H., James, A., & Ginis, J. (1997). Client oriented scale of improvement (COSI) and its relationship to several other measures of benefit and satisfaction provided by hearing aids. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 8(1), 27–43.

Fitzgerald, M., Ward, K., Gianakas, S., Smith, M., Blevins, N., & Swanson, A. (2024). Speech-in-noise assessment in the routine audiologic test battery: Relationship to perceived auditory disability. Ear and Hearing, 45(4), 816–826. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000001472

Gatehouse, S., & Elberling, C. (1999). Aspects of auditory ecology and psychoacoustic function as determinants of benefits from and candidature for non-linear processing in hearing aids. Danavox Symposium.

Gatehouse, S., Naylor, G., & Elberling, C. (2006). Linear and nonlinear hearing aid fittings—2. Patterns of candidature. International Journal of Audiology, 45(3), 153–171.

Hey, M., Mewes, A., & Hocke, T. (2023). Speech comprehension in noise—Considerations for ecologically valid assessment of communication skills ability with cochlear implants. HNO, 71(Suppl 1), 26–34.

Holman, J. A., Hornsby, B. W. Y., Bess, F. H., & Naylor, G. (2021). Can listening-related fatigue influence well-being? Examining associations between hearing loss, fatigue, activity levels, and well-being. International Journal of Audiology, 60(Suppl 2), S47–S59. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2020.1853261

Hornsby, B. W. Y., Camarata, S., Cho, S.-J., Davis, H., McGarrigle, R., & Bess, F. H. (2021). Development and validation of the Vanderbilt fatigue scale for adults (VFS-A). Psychological Assessment, 33(8), 777–788.

Hornsby, B. W. Y., Camarata, S., Cho, S. J., Davis, H., McGarrigle, R., & Bess, F. H. (2023). Development and validation of a brief version of the Vanderbilt Fatigue Scale for Adults: The VFS-A-10. Ear and Hearing, 44(5), 1251–1261. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000001369

Huda, N., Banda, K. J., Liu, A. I., & Huang, T. W. (2023). Effects of music therapy on spiritual well-being among patients with advanced cancer in palliative care: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 39(6), Article 151481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2023.151481

Humes, L. E. (2007). The contributions of audibility and cognitive factors to the benefit provided by amplified speech to older adults. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 18(7), 590–603.

Humes, L. E., Rogers, S. E., Main, A. K., & Kinney, D. L. (2018). The acoustic environments in which older adults wear their hearing aids: Insights from datalogging sound environment classification. American Journal of Audiology, 27(4), 594–603. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_AJA-18-0061

Jorgensen, E., Xu, J., Chipara, O., Oleson, J., Galster, J., & Wu, Y.-H. (2023). Auditory environments and hearing aid feature activation among younger and older listeners in an urban and rural area. Ear and Hearing, 44(3), 603–618.

Klein, K. E., Wu, Y. H., Stangl, E., & Bentler, R. A. (2018). Using a digital language processor to quantify the auditory environment and the effect of hearing aids for adults with hearing loss. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 29, 279–291.

Lelic, D., Picou, E., Shafiro, V., & Lorenzi, C. (2025). Sounds of nature and hearing loss: A call to action. Ear and Hearing, 46(2), 298–304. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000001601

Lin, Y., & Li, Q. (2025). Efficacy of music therapy for depressive symptoms in college students: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, Article 1576381. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1576381

Mick, P., Kawachi, I., & Lin, F. R. (2014). The association between hearing loss and social isolation in older adults. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 150(3), 378–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599813518021

Moore, B. C. J. (2016). A review of the perceptual effects of hearing loss for frequencies above 3 kHz. International Journal of Audiology, 55(12), 707–714.

Moore, B. C., & Sęk, A. (2016). Preferred compression speed for speech and music and its relationship to sensitivity to temporal fine structure. Trends in Hearing, 20. https://doi.org/10.1177/2331216516640486

Mueller, H. G., & Hornsby, B. W. Y. (2020). 20Q: Word recognition testing—Let's just agree to do it right! AudiologyOnline. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com/articles/20q-word-recognition-testing-let-26478

Mueller, H. G., Ricketts, T., & Hornsby, B. W. Y. (2023). 20Q: Speech-in-noise testing—Too useful to be ignored! AudiologyOnline. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com/articles/20q-speech-in-noise-testing-too-28760

Noble, W., Jensen, N. S., Naylor, G., Bhullar, N., & Akeroyd, M. A. (2013). A short form of the Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing scale suitable for clinical use: The SSQ12. International Journal of Audiology, 52(6), 409–412.

Oldenberg Hearing & Health Workshop. (2022). Music Hearing Health Workshop. https://uol.de/music-hearing-health-workshop

Pichora-Fuller, M. K., Kramer, S. E., Eckert, D., Edwards, B., Hornsby, B. W. Y., Humes, L. E., Lemke, U., Lunner, T., Mackersie, C. L., Naylor, G., Phillips, N. A., & Tremblay, K. L. (2016). Hearing impairment and cognitive energy: The framework for understanding effortful listening (FUEL). Ear and Hearing, 37(Suppl 1), 5S–27S.

Peelle, J. E., & Wingfield, A. (2016). The neural consequences of age-related hearing loss. Trends in Neurosciences, 39(7), 486–497.

Salvago, P., Vaccaro, D., Plescia, F., Vitale, R., Cirrincione, L., Evola, L., & Martines, F. (2024). Client oriented scale of improvement in first-time and experienced hearing aid users: An analysis of five predetermined predictability categories through audiometric and speech testing. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(13), Article 3956. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13133956

Sandgren, P., & Alexander, J. M. (2023). Music quality in hearing aids. Audiology Today, 35(4).

Smoorenburg, G. F. (1992). Speech reception in quiet and in noisy conditions by individuals with noise-induced hearing loss in relation to their tone audiogram. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 91(1), 421–437.

Taghvaei, N., & Taylor, B. (2025). Measuring listening-related fatigue in the clinic: Effects of hearing aid use. [Poster presentation]. American Academy of Audiology meeting, New Orleans, LA, United States.

Taylor, B. (2007). Predicting real world hearing aid benefit with speech audiometry: An evidence-based review. AudiologyOnline. https://www.audiologyonline.com/articles/predicting-real-world-hearing-aid-946

Winn, M. (2025). 20Q: Listening effort—Understanding its role in audiology and patients' lives. AudiologyOnline. https://www.audiologyonline.com/articles/20q-listening-effort-understanding-its-29239

Wu, Y. H., & Bentler, R. A. (2012). Do older adults have social lifestyles that place fewer demands on hearing? Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 23(9), 697–711.

Young, T. (2024). Enhancing the COSI goal-setting discussion. National Acoustic Laboratories. https://www.nal.gov.au/projects/enhancing-the-cosi-goal-setting-discussion

Appendix 1

Aided Speech Intelligibility: Wearer Priorities and Scientific Evidence

Improved speech intelligibility is often the top priority for hearing aid wearers, and it is often cited as the biggest improvement experienced wearers seek when re-purchasing new hearing aids. This statement is supported by multiple studies and surveys. Here is a list of recent publications supporting this assertion:

- Appleton J. What is important to your hearing aid clients… and are they satisfied?. Hearing Review. 2022;29(6):10-16.

- Desai, N., Beukes, E. W., Manchaiah, V., Mahomed-Asmail, F., & Swanepoel, W. (2024). Consumer Perspectives on Improving Hearing Aids: A Qualitative Study. American Journal of Audiology, 33(3), 728–739. https://doi.org/10.1044/2024_AJA-23-00245

- Manchaiah, V., Picou, E. M., Bailey, A., & Rodrigo, H. (2021). Consumer Ratings of the Most Desirable Hearing Aid Attributes. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 32(8), 537–546. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1732442

- Picou E. M. (2022). Hearing Aid Benefit and Satisfaction Results from the MarkeTrak 2022 Survey: Importance of Features and Hearing Care Professionals. Seminars in Hearing, 43(4), 301–316. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-1758375

There is also ample evidence demonstrating that the best way to improve speech intelligibility with hearing aids is by optimizing effective audibility of speech, which is best done by matching a validated prescriptive gain target (e.g., NAL-NL2). Here is a sampling of the studies suggesting this claim:

- Brennan, M. A., Browning, J. M., Spratford, M., Kirby, B. J., & McCreery, R. W. (2021). Influence of aided audibility on speech recognition performance with frequency composition for children and adults. International Journal of Audiology, 60(11), 849–857. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2021.

- Ching, T. Y., Dillon, H., Katsch, R., & Byrne, D. (2001). Maximizing effective audibility in hearing aid fitting. Ear and Hearing, 22(3), 212–224. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003446-200106000-00005

- Leavitt, R. (2021). 20Q: In pursuit of audibility for people with hearing loss. AudiologyOnline, Article 27848. Available at www.audiologyonline.com

Appendix 2

What is Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA)

A technical term used by hearing aid researchers, EMA refers to collecting hearing aid wearer information using a smartphone app. More precisely, Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) in hearing aids is a method using smartphone-based questionnaires to collect real-time data from hearing aid wearers about their listening experiences and challenges as they happen. As the term implies, it offers a realistic picture of hearing aid performance in diverse, everyday listening environments, rather than the limited scenarios of a laboratory. EMA is used extensively in hearing aid research but has yet to become a popular clinical tool.

Instead of relying on retrospective, “pen and paper” questionnaires, which can be inaccurate due to memory bias (e.g., forgetfulness), EMA allows researchers and clinicians to gather data with higher ecological validity by assessing situations as they happen. There are at least three ways researchers use EMA in their studies.

- Subjective data: Hearing aid wearers are prompted via a smartphone app to report on their current listening situation, including their satisfaction, listening effort, and perception of sound quality.

- Objective data: While the hearing aid wearer is answering a questionnaire, the hearing aid app can collect objective acoustic data, such as sound pressure levels and noise classification, from the hearing aids via Bluetooth.

- Personalized feedback: The data gathered through EMA can help audiologists fine-tune hearing aid settings to a patient's individual needs during fittings and follow-up appointments.

Although EMA can collect real-time, context-rich data with memory bias, it does have a couple of limitations.

- Underrepresented social situations: In some studies using EMA, it has been documented that some participants were less likely to answer questionnaires during social situations like conversations or at church. (It’s still considered rude to use your phone in these situations.) This means that data for these important, challenging acoustic environments were often underrepresented.

- Technological compliance: Objective data can be biased if wearers don't consistently carry their smartphones, as a Bluetooth connection is required for data logging.

Citation

Taylor, B. (2025). Beyond speech intelligibility: Expanding the clinician’s role in assessing the individual’s auditory ecology. AudiologyOnline, Article 29406. Available at www.audiologyonline.com