Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Describe the general FDA classifications of OTC hearing aids.

- Describe the preliminary findings of the 2025 MarkeTrak survey.

- Describe the demographics of the U.S. market for OTC hearing aids.

- Describe performance variables that could have influenced the findings of the comparative studies.

- Identify areas where audiologic intervention would be beneficial for OTC users.

Introduction

Over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aids, launched as a new FDA-regulated medical device category in October 2022, primarily exist to address the poor uptake of traditional hearing aids. Resulting from persistent affordability and access issues, OTCs are believed by many to be a low-cost, easy-to-buy alternative to traditional hearing aids and in-person hearing care. Unfortunately, with the arrival of the OTC hearing aids as an official FDA-regulated product category, has come muddle and misinformation.

Today, for example, there exist three different types of OTCs that stand alongside prescription hearing aids and other types of unregulated amplifiers as options for individuals with perceived mild to moderate hearing loss. All these devices, even those labeled “prescription hearing aids”, can be purchased through the direct-to-consumer (DTC) buying channel. Adding to the confusion, OTCs are available in a bewildering range of prices with inconsistent labeling that can baffle even the most tech-savvy consumers.

While OTC hearing aids have existed as an FDA-regulated product category for less than three years, their precursors have been studied for a long time. This year marks the 20th anniversary of the first peer-reviewed study that investigated the effects of over-the-counter hearing aids—at least, it is the first study of its kind that we know of. In that study, McPherson and Wong (2005) fitted 19 individuals, aged 62 and older, with a low-cost, OTC-like alternative. Using a series of validated outcome measures, including the COSI and IOI-HA, and after each study participant wore the devices for about 90 days, they found these OTC-like products provided meaningful benefit.

Years later, similar studies began to trickle into the refereed literature. A randomized, placebo-controlled study (Humes et al., 2017) comparing the benefits of prescription hearing aids fitted using an OTC-like approach versus an audiologist-fitted device found only a small advantage for the audiologist-fitted hearing aids. More recently, DeSousa et al. (2023) evaluated a self-fitted OTC device in the same manner; again, results demonstrated favorable patient outcomes with OTC-like devices.

Finally, Convery et al. (2019) investigated factors influencing the successful setup of self-fitting hearing aids and the need for personalized support during the process. The aim of this study was to identify predictors of success, assess the necessity for assistance, and evaluate the performance of individual steps in the self-fitting procedure. They found that 68 percent of the study participants could successfully self-fit hearing aids with minimal or no assistance from a professional.

In Research Quick Takes Volume (RQT) Volume 5, published just two years ago, we discussed these studies and many others. Although these earlier studies are still relevant, all of them have one major drawback: FDA-approved OTC hearing aids did not yet exist when they were conducted. Instead, researchers retrofitted what we now call prescription hearing aids into OTC-style or OTC-like devices. Additionally, in these early OTC studies, licensed professionals provided considerable oversight of the study participants’ entire wearing experience – something that is unlikely to occur in the current OTC marketplace.

Here in RQT, Volume 10, we revisit OTC hearing aids. Now, three years after the FDA regulations have been in effect, we have peer-reviewed studies evaluating actual OTC hearing aids. We have divided this RQT into two main sections: Consumer-based and performance-based studies. The consumer-based studies reviewed here examine several aspects of the OTC buying process from the consumer’s perspective. Given that the intended buyer of OTCs is adults with perceived mild to moderate hearing loss who choose to self-direct their care, it is critical to better understand their behaviors and buying habits, and how they may differ from those who choose to acquire prescription hearing aids from licensed professionals.

In contrast, the performance-based studies reviewed here, for the most part, examine how specific parameters like the hearing aid pre-sets, gain, and output selected by the patient, and subsequent measured benefit, compare to prescriptive hearing aids fitted in a clinic by licensed professionals.

A Little More History

While the official introduction of the OTC category was only three years ago, there was considerable activity in the years leading up to this announcement. Here is a brief review (Powers, 2022; Taylor & Mueller, 2023):

- On August 7, 2003, Mead Killion, president of Etymotic Research, filed a petition that called for a hearing aid that could be sold over-the-counter as an affordable alternative to custom hearing aids. The device would cost an estimated $100 to $300. Citing a concern for public health (e.g., medical clearance for hearing aids), the FDA turned down the petition in 2004.

- Five years later, serious discussions regarding the need for access and affordability of hearing aids for the general public began back in 2009 at an NIH conference.

- The topic was later picked up by the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, and then by the National Academy of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM). In 2016, the latter group issued a set of 12 recommendations concerning the OTC product.

- The NASEM recommendations led to the introduction of the Over-the-Counter Hearing Aid Act by Senators Grassley and Warren in 2016. It was passed and signed into law by President Trump in 2017, requiring the FDA to have guidelines in place by August 2020. There was a delay, however, reportedly due to the pandemic.

- In October 2021, the FDA released the draft regulations with a 60-day comment period. Over 1000 comments were submitted.

- After five years of waiting, the 200-page document was finally filed on August 16, 2022, at 8:45 am (EDT) and went into effect on October 17, 2022.

New Hearing Aid Categories

As we mentioned in our introduction, we now have three general classes of OTC hearing aids (Bailey, 2025):

- Self-fitting OTC hearing aids: Using smartphone-based fitting apps and automated testing, gain and output is selected by the patient.

- Preset-based OTC hearing aids: The patient selects the amplification from existing generic amplification profiles

- Hearing aid software: Converts existing hardware into a pair of OTC hearing aids (e.g., Apple AirPods).

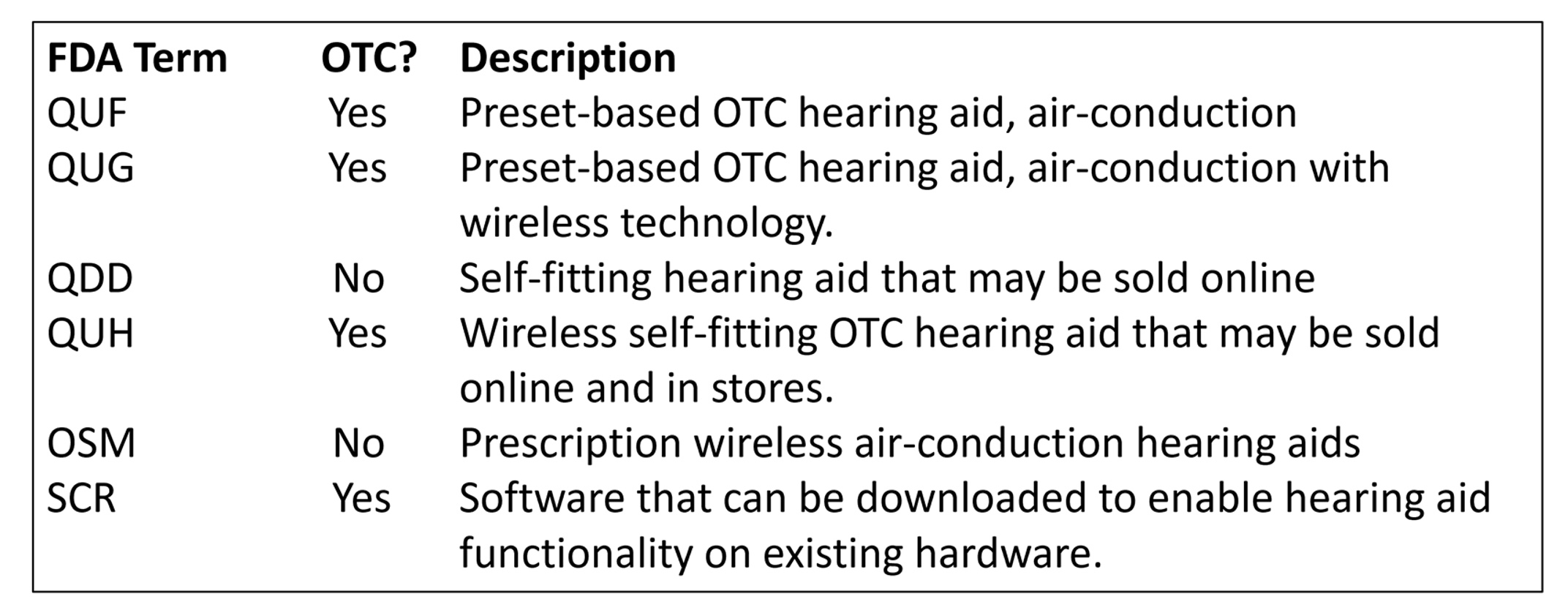

In addition to the three general classes, we have six different FDA classifications, which are shown below (adapted from Bailey, updated February 9th, 2025). To put this into perspective, when Bailey published the summary below in February 2025, there were 142 OTC products available—that number has most probably increased at this reading.

Table 1. Six different FDA classifications of hearing aids (Bailey, 2025).

Additional Terminology

There are also products that are not regulated by the FDA and therefore, not listed in Table 1. There are many, many hearing-aid-like products that amplify sounds, most of which are available through alternative buying channels, most commonly the internet. These unregulated amplifiers historically have been referred to as Personal Sound Amplification Products (PSAPs, or Pee-Saps). Technically, PSAPs should be used by people with normal hearing who want enhancement of environmental sounds, like bird watchers. (This is, of course, seldom-followed guidance). Most PSAPs, undoubtedly, are purchased by persons with hearing loss.

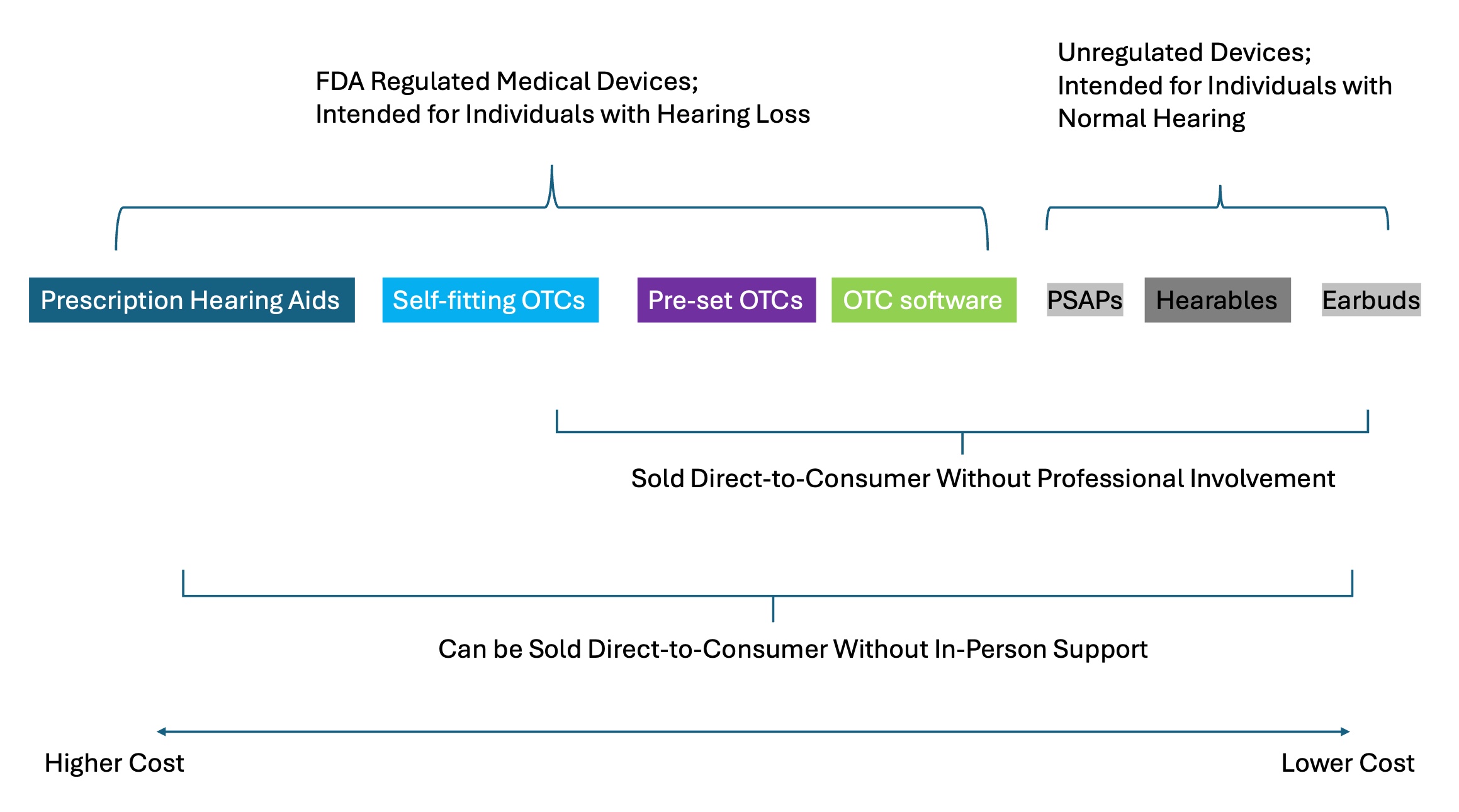

Today, PSAPs are often placed in a category referred to as Direct-To-Consumer (DTC). The term DTC, however, refers to a buying channel, not a product. A buying channel is probably best defined as the way or place a customer makes a purchase, whether it's through a physical store or online. It's the specific avenue through which a customer finds, evaluates, and ultimately buys a product or service. Because of the way prescription hearing aids are labelled and regulated (a complicated mix of state and federal rules), similar to PSAPs and OTCs, they can also be purchased in the DTC buying channel—a “hearing aid” search on Amazon or eBay provides a pretty descriptive example of this. As illustrated in Figure 1, the DTC buying channel is more of an umbrella term, one that describes how any amplification device can be purchased by a customer.

A PSAP by Any Other Name

There are other terms used to describe unregulated amplification devices. Figure 1 shows two other terms, besides PSAPs, often associated with these amplifiers, unregulated by the FDA. Those two terms are hearables and smartphone apps paired to a consumer audio device. A hearable is nothing more than a catchy advertising term used to sell a PSAP. For that reason, when you see the term, hearable, think PSAP.

Figure 1. The current hearing amplifier landscape, circa 2025.

In general, PSAPs are of lesser quality, but also lower priced, than the OTCs that have been approved by the FDA, often no more than $100/pair. Because PSAPs are unregulated, however, their quality is highly uneven. The inconsistent quality of PSAPs is demonstrated in a review article by Maidment et al. (2025). They conducted a systematic review of 14 studies, ten of which assessed PSAPs and four that evaluated smartphone apps paired with a hearable. All the devices used in the studies they reviewed were fitted by trained staff in a clinic using best practices.

The primary objective of their systematic review was to assess the effect of PSAPs on speech intelligibility in noise performance compared to traditional hearing aids. They classified PSAPs and hearing aids that were used in these studies as either premium or basic, based on the number of channels of compression. The four “amplifier” apps + hearables were classified as basic. Their meta-analyses showed that basic PSAPs did not outperform the unaided condition. On the other hand, premium PSAPs improved speech intelligibility in noise performance compared to unaided. They also determined that premium hearing aids performed better than premium and basic PSAPs, smartphone app + hearable, and basic hearing aids.

The results of their systematic review suggest that premium PSAPs that have 16 or more compression channels function similarly to prescription hearing aids and would be a suitable alternative to prescription hearing aids for individuals who cannot afford, or do not wish to use, premium hearing aids. On the other hand, given the poor performance of basic PSAPs and smartphone apps + hearables, they are poor substitutes for prescription hearing aids and should be avoided.

Maidment et al. (2025) findings underscore an important consideration related to both PSAPs and OTC hearing aids: inconsistent terminology (e.g., PSAPs vs. hearables) contributes to public misunderstanding and confusion of OTC hearing aids. This is an issue we revisit in the consumer-based studies, reviewed in this Research Quick Takes.

A Look at the Research

In this volume of Research Quick Takes, we review some of the more salient articles that have been published regarding OTC hearing aids in the last few years, considering that OTC only became OTC in October 2022. Obviously, the most important question, for both researchers and clinicians, is: re OTC hearing aids a reasonable alternative to prescriptive products for a portion of those individuals who are candidates for hearing aids? The answer to this is somewhat related to one’s definition of “reasonable alternative.” The Maidment et al. (2025) article we just reviewed addresses this issue.

Let’s say that an OTC fitting (self-fitting) results in the patient using 5-8 dB less gain for average inputs, and 8-12 dB less gain for soft inputs, than would be specified by a validated prescriptive method, and verified by an audiologist on the day of the fitting. Will this result in less-than-optimal outcomes? Very likely. Is it better than not using any hearing aids at all? Probably. Are there prescription hearing aids being fitted just as poorly? Most certainly, maybe the majority—this could be one way to rationalize that a mediocre OTC fitting is “okay!”

This is just one example of OTC vs Prescription issues that need answers based on well-designed research. There are several factors to be sorted out, more than what could be controlled for in a single research design, but all of which could drive the outcome. Here are some examples:

- Good sound quality for speech.

- Good sound quality for music.

- Input and output compression that will assist in normalizing aided loudness while keeping loud inputs below the patient’s LDL.

- Advanced directional technology and noise reduction, which might assist in understanding speech in background noise.

- Effective feedback reduction, which, if not present, could influence presets.

- For self-fitting products: A fitting approach that will result in a final fitting at or near the targets of validated methods for a wide range of inputs.

- For preset products: A threshold testing method and corresponding presets that will result in a final fitting at or near the targets of validated methods for a wide range of inputs.

- Form factor: OTCs are available, ranging from relatively large BTE instruments to in-the-canal (ITC) models.

- Usability: The self-fitting procedure and use of apps differ among products.

- Assistance provided at the time of the initial fitting and adjustment.

- Long-term assistance provided following the fitting.

Either directly or indirectly, you’ll find that we’ll touch on almost every factor listed above in our reviews of the articles selected. There of course are many other more general topics to discuss, such as patient journey, distribution channels, role of the audiologist, economic outcomes, benefit-cost analysis, labeling, safety, information seeking, values of hearing health, and so on. We’ll save all those for another day.

To give you a snapshot of what is happening in the world of OTC research, we’ll call out some representative publications. The first section deals with consumer-based studies, which will then be followed by a section that has mostly “performance-based” findings.

Sample of Representative Articles

Consumer-based Research

Unlike prescription hearing aids, OTCs are often sold directly to patients without any involvement from a licensed professional. Because there is no direct professional involvement, and OTCs exist alongside prescription hearing aids, this presents several interesting questions for researchers to study.

- How do consumers (we deliberately refer to an OTC buyer as a consumer, rather than a patient) learn about and buy OTC hearing aids?

- Do consumers know the difference between OTCs, PSAPs, and prescription hearing aids?

- How big is the demand for OTC products?

- What type of consumers would rather buy hearing aids online?

- How much would a consumer be willing to pay for an OTC?... a prescription hearing aid?... audiology services?

Many questions to answer - some of which are addressed in the studies reviewed here. We’ll start things off with some general preliminary findings from MarkeTrak 2025.

Interpreting the Hearing Health Landscape through MarkeTrak - From Insight to Impact (Dobyan, 2025)

General Research Question: Going back to 1989, the Hearing Industries Association (HIA) has conducted U.S.-based population studies focused on the hearing aid market. The MarkeTrak surveys, conducted every two to three years, provide valuable insights for the industry. This is the first MarkeTrak survey to include questions specific to the OTC product.

What They Did: The survey was fielded in late 2024, reaching 42,982 individuals. Of this total, 2,955 respondents reported hearing difficulty. Of this target population, 1,173 were hearing aid owners and 1,782 were non-owners. In many of the categories studied, independent data for the OTC owners was extracted. Several questions were designed to validate data across multiple points, to help differentiate OTC buyers from traditional hearing aid wearers.

What They Found: There has not been a substantial change in adoption rates since the introduction of OTCs—38.4% for the MarkeTrak 2022 vs. 39.1% for MarkeTrak 2025.

- The highest adoption rates for traditional hearing aids are in the 65 and up age category, while the highest OTC rates are in the 34 and younger demographic.

- More OTC buyers tend to be first-time buyers (70% versus 58% of traditional hearing aid owners).

- Hearing aid use: 69% of traditional hearing aid owners wear their hearing aids daily; 55% of OTC owners do so.

- For OTC owners who plan to purchase new hearing aids in the next few years, over half think that they will buy in person from an HCP.

- Sixty percent of OTC owners who did not receive professional assistance believed that it would have been beneficial along the way.

Our Take: First, considering the myriad of names associated with amplifiers sold directly to consumers (see Figure 1), we believe it is impossible to know with great certainty the adoption rates of OTCs. When surveyed, after all, many respondents simply don’t know what type of amplifier they are wearing. However, since HIA uses a scientific and consistent analysis of their survey data, their numbers are probably closer to many others’ estimates. Second, their survey results bode well for the future of the audiology profession. If OTCs do, in fact, tend to attract younger, first-time buyers, these are the same individuals who, as they age, will seek the care of an audiologist. Finally, as mentioned, this is a preliminary report. For a more extensive summary of MarkeTrak 2025 findings, with more data regarding the OTC product, look for a special issue of Seminars in Hearing (open-access), Issue 4, due out in November 2025.

OTC Market Size

Maybe the most basic consumer-based question is the potential market size. How many individuals in the U.S. might be candidates for OTC hearing aids? A question addressed in this 2024 study.

Demographic and Audiological Characteristics of Candidates for Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids in the United States (Humes, 2024)

General Research Question: What are the demographic and audiologic characteristics of U.S. adults with self-perceived mild-to-moderate hearing trouble - the primary target group for over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aids per the 2022 FDA regulations?

What He Did: Using data from three recent NHANES cycles with audiological information: 2011–12, 2015–16, and 2017–20, self-reported mild-to-moderate hearing trouble was used as a proxy to identify the approximate number of U.S. adults who fit the audiologic candidacy criteria for OTC hearing aids.

What He Found: An estimated 49.5 million U.S. adults have perceived mild-to-moderate hearing trouble and would be potential OTC hearing aid candidates. This group is largely aged 50–69, non-Hispanic White, married, educated, with middle-income backgrounds. Despite significant communication barriers, most had not sought hearing exams or used hearing aids. Among 20–69-year-olds with self-reported mild-to-moderate hearing trouble, only ~5% had ever used a hearing aid or assistive listening device. However, device usage jumped to ~20 to 35% for those aged 70 to 80+ years old.

Our Take: This study confirms that many individuals who meet the OTC audiometric requirement do not wear prescription hearing aids. For this group, OTCs are a promising way to improve accessibility to hearing aids, especially for adults with self-reported mild to moderate hearing trouble under the age of 70 who have never tried hearing aids.

Profile of Potential OTC Buyers: Is it Different Than Prescription Hearing Aid Buyers?

It is well known that the intended target of OTC hearing aids is adults with perceived mild to moderate hearing loss. As Humes (2024) found (cited above), most OTC hearing aid candidates are aged between 50 and 69 years. Approximately 40–45% of individuals with mild-to-moderate hearing trouble fall within this age range. Additionally, about 15% are aged 40–49 years, and another 15% are aged 70–79 years. This indicates that about three-fourths of potential OTC hearing aid buyers are between 40 and 79 years old. Now that OTCs have been available for a few years, we can compare Humes' projections to some actual data. According to MarkeTrak 2025, the self-reported average age of an OTC buyer is 52 years. There are a few other demographic data points we might be able to cite here.

Although knowing the average age of a prospective OTC buyer is helpful, it is just a small part of the equation. There are several other variables, often referred to as psychographics, that help us determine the profile of an OTC buyer and how it might differ from the profile of a prescriptive hearing aid wearer. One study examined the profile of individuals who may choose OTC over prescription hearing aids.

Reasons for Hearing Aid Uptake in the United States: A Qualitative Analysis of Open-Text Responses from a Large-scale Survey of User Perspectives (Knoetze, Beukes, et al., 2024)

General Research Question: From the perspective of the individual with hearing loss, how does the profile of an OTC buyer differ from a prescription hearing aid wearer?

What They Did: This was a cross-sectional survey of 642 adult hearing aid wearers, taken from the Hearing Tracker and Lexie Hearing databases in the United States. Participants included 415 hearing aid buyers from the Hearing Tracker who obtained prescription hearing aids, and 227 individuals from the Lexie Hearing database who obtained OTC-like devices (we say “OTC-like” because they were purchased before the 2022 FDA guidelines went into effect). Remote clinical services were available via a DTC delivery model. A single open-ended question on reasons for hearing aid uptake and recommendations to others with hearing difficulties was asked to all respondents. The researchers conducted qualitative content analysis of the open-ended wearer responses to that question.

What They Found: OTC hearing aid buyers were slightly younger (mean age for prescriptive buyers was 66.4 years, OTC buyers were 63.7 years). Additionally, OTC buyers had a shorter duration of hearing loss and had milder self-reported hearing difficulties compared with prescription hearing aid wearers.

There were also important differences between the two groups in the reasons they purchased hearing aids. OTC buyers tended to be more motivated by social factors, such as difficulty interacting socially with friends. They are also more likely to seek affordable solutions and prefer the convenience of self-fitting devices. OTC hearing aid buyers also reported taking up hearing aids because of listening fatigue 2.3 times more often.

On the other hand, prescription buyers reported consequences of untreated hearing loss as a motivating factor for hearing aid uptake 5.5 times more often. Prescription hearing aid buyers were more likely to mention cognitive decline and dementia as reasons for purchasing hearing aids.

Our Take: Even though the average age difference between the OTC and prescription buyers is less than three years, this study shows some revealing differences between the two groups. The OTC buyers seem to be motivated by hearing problems in social situations, while the prescription buyers, perhaps because they are coping with other chronic health problems, are more tuned into some of the co-morbidities associated with hearing loss and aging. These differences between the two groups could be used in marketing campaigns that promote OTCs and prescription hearing aids. OTCs could be promoted as a solution to improve socializing, and prescription hearing aids could be promoted as a solution to improve healthy aging.

The OTC Buying Experience

These days, one of the most popular places to buy any product is Amazon. So, it’s reasonable to expect many OTC-curious individuals simply log into their Amazon account to read reviews and possibly buy a pair of OTC hearing aids. The next group of studies examines information quality and the online buying experience.

Benefits and Shortcomings of Direct-to-Consumer Hearing Devices: Analysis of Large Secondary Data Generated from Amazon Customer Reviews (Manchaiah et al., 2019)

General Research Question: What are the perceived benefits and shortcomings of direct-to-consumer (DTC) hearing devices based on user-generated Amazon customer reviews?

What They Did: The researchers employed text mining and content analysis techniques to extract and categorize consumer sentiments related to direct-to-consumer hearing aids. They analyzed 11,258 Amazon reviews of direct-to-consumer hearing devices (remember this study was conducted before OTCs became an official product category) to uncover marketing and other user experience dynamics.

What They Found: Some of the characteristics of direct-to-consumer hearing aids with positive reviews included accessibility, affordability, and ease of use. Negative reviews were more likely to be associated with poor sound quality, insertion difficulty, and Bluetooth/connectivity.

Our Take: While this study was conducted six years ago, it seems likely that similar findings would be present with today’s OTC products.

Understanding Public Perception of Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids: A Sentiment and Thematic Analysis of Consumer Reviews (Cho et al., 2025)

General Research Question: What is the consumer perception of over‐the‐counter (OTC) hearing aids?

What They Did: Similar to Manchaiah et al. (2019), the researchers used thematic and cluster analysis of online consumer reviews to assess 21,727 consumer reviews, written between 2016 and 2024 across platforms, including Amazon.

What They Found: Reviews for OTC and DTC devices were generally positive, with higher-cost and BTE models receiving the highest reviews. The positive clusters included affordability and time saving compared to prescription aids, while the negative clusters were subpar sound quality, poor customer service, and insufficient amplification for patients with more severe hearing loss.

Our Take: Although this analysis of online reviews didn’t examine OTC hearing aids per se, it does highlight the benefits and shortcomings of the online buying experience of them. Together, both studies show from the consumer’s perspective the pros and cons of direct-to-consumer hearing aids. These studies also shed light on how limitations of DTC buying could be addressed by audiologists delivering in-person care.

Labeling and Terminology Issues

The FDA’s 2022 OTC regulations clearly state that manufacturers must adhere to labeling standards, which include clear statements of intended user group (i.e., adults with perceived mild-to-moderate hearing loss). However, it is commonly reported that many Amazon listings lack transparent labeling, leading to misleading product descriptions. Ultimately, inaccurate labeling can lead to considerable consumer confusion.

Another discrepancy in how OTC hearing aids are advertised online is related to FDA labeling and the terms FDA-registered versus FDA-cleared. FDA- registered means the devices have simply been registered with the FDA and meet some basic safety standards. In contrast, FDA-cleared, a higher regulatory bar, indicates the FDA has reviewed and determined that the device is substantially equivalent to a legally marketed device. All OTC hearing aids must be registered with the FDA, while self-fit OTCs must be FDA-cleared.

Just how much does Amazon's advertising ecosystem blend FDA-registered and FDA-cleared hearing aids with PSAPs, muddying the water between prescription hearing aids, OTCs, and PSAPs, was the focus of the next study.

Marketing practices and information quality for OTC hearing aids on Amazon.com (Conway et al., 2025)

General Research Questions: What is the status of FDA-labeling requirements for OTC hearing aids as listed on Amazon? What are the price ranges, product descriptions, and consumer satisfaction ratings of OTC hearing aids advertised on Amazon?

What They Did: On a single day (April 3, 2024), the researchers conducted a keyword search of “OTC hearing aids” and collected results for the first 3 pages of their search. This resulted in 138 individual listings of products labeled “OTC hearing aids.” They conducted a readability analysis of their keyword search results. Key data extracted included price, device type (i.e., self-fit vs pre-set), and FDA clearance status.

What They Found: Prices range from under $200 to over $2,000 for products labeled “OTC hearing aids.” Approximately two-thirds of these devices listed on Amazon identified their product as “OTC hearing aids”, with less than 30% of them verified as FDA-cleared OTCs. Some of these “OTC hearing aids” are not OTC hearing aids at all; instead, they are personal sound amplification products (PSAPs). Additionally, 9% of the listings were marketed to individuals with hearing loss beyond mild-to-moderate, and nearly 40% of the listings lacked specific marketing for mild-to-moderate hearing loss.

Our Take: Results of this study demonstrate the remarkable inconsistencies in pricing, marketing, and labeling, including erroneous and misleading FDA clearance claims of hearing devices sold directly to the consumer. These discrepancies in the online shopping experience are sure to confuse many potential OTC hearing aid wearers. Given these discrepancies and inaccuracies, audiologists must be prepared to allay buyer confusion and dispel misinformation surrounding the various types of non-prescription amplifiers that are commercially available online.

Comprehension and Use of the Over-the-Counter Hearing Aid Product Information Label (Singh et al., 2025)

General Research Questions: How well do consumers understand the OTC hearing aid product information label’s content? And, how do consumers visually engage with the FDA‑required product information label (PIL)?

What They Did: A group of 40 participants were divided into two groups—those fluent only in English (EO) and those for whom English was a second language (ESL). Using experimental eye tracking, participants viewed an OTC hearing aid package (including its PIL) while their gaze and fixation patterns were tracked to see which parts drew attention and for how long. After viewing the PILs, participants answered questions testing their understanding of the PIL’s key information.

What They Found: There were a few findings of note:

- Comprehension deficits were noted, especially among ESL consumers. Most of the label’s health‑related information was not understood by ESL participants, suggesting significant accessibility issues.

- Minimal sustained attention was given to the PIL by both EO and ESL groups—participants did not linger to read or study the label’s content.

- The current PIL format fails to effectively attract attention or communicate vital information, particularly for ESL users, indicating it may not serve its intended purpose without redesign.

Our Take: Consistent with Conway et al (cited above), this study suggests the FDA is not delivering on its intended goal of providing consumers with clear and usable health-related information. Given the lack of a licensed professional in the buying process, these findings indicate that OTC manufacturers need to invest more resources into ensuring their product labels reflect the best interests of consumers.

Misjudgments of Hearing Loss and its Implications for OTC use (Hamburger et al., 2025)

General Research Questions: Can individuals accurately perceive their own hearing loss—particularly whether they over- or underestimate it? And, how do these potential misjudgments impact the self-selection of OTCs, which are intended for individuals with perceived mild-to-moderate hearing loss?

What They Did: The researchers conducted a retrospective chart review in a medically-based audiology practice. The audiograms of 116 patients were reviewed. Before each audiogram, patients estimated the severity of their hearing loss on a 6-item scale: no hearing loss, mild, moderate, moderately severe, severe and profound. Audiometric data were then obtained for thresholds at 500, 1000, 2000, and 000 Hz. These frequencies were chosen by the researchers because they are critical to speech comprehension and results at these test-frequencies are often used by clinicians to determine candidacy for prescription hearing aids. Researchers then compared subjective self-assessments with objective audiometric results to determine accuracy of self-candidacy for OTC devices.

What They Found: Many consumers misjudge their hearing loss—either underestimating or overestimating it, which could lead to improper self-selection of OTC candidacy. Among those with moderate or worse hearing loss, 57% believed their loss was less severe and thus wrongly thought they were eligible for OTCs. On the other hand, among those with mild-to-moderate loss, as measured on their audiogram, 51% perceived their loss as worse than measured and would likely forgo OTC devices.

Our Take: This study shows that nearly half of adults seeking hearing care (going to an in-person appointment for a hearing test at a medical clinic) misperceive their hearing loss severity, posing a risk of either under- or over-treatment when using OTC hearing aids. First, although this relatively large number of over- and under-estimators may not reflect the commercial market (the individuals in this study were proactively seeking in-person care), it nevertheless indicates that OTC manufacturers would be wise to incorporate some type of validated questionnaire into their buying process that helps consumers self-screen for OTC candidacy. Second, while OTC labeling requirements plainly state that a hearing test is not needed, these findings indicate consumers should be encouraged to seek a standardized hearing test from a licensed professional prior to buying OTCs.

Consumer Behavior and Buying Habits

Considering OTC and prescription hearing aids stand alongside each other as options for individuals with hearing loss, it is important to learn more about the type of person who might choose OTC over prescription hearing aids. Understanding the buying habits and other consumer behaviors that drive these choices is not new in the retail business. It is a powerful tool for understanding target audiences for products and creating more effective marketing strategies by going beyond surface-level demographics and exploring the deeper motivations and behaviors that drive customer buying habits.

A common type of marketing research is referred to as “customer archetype research”, something pioneered in the highly competitive automobile industry. Considering that consumer archetype research is now being conducted by audiologists reflects the commercial evolution of the profession now that consumers have alternatives to traditional hearing aids. Archetype research attempts to understand what drives customers on a deeper level, allowing for more personalized and pinpointed marketing of products. The first archetype research in audiology that we know of was published in 2023. It is not surprising that the focus of this research was on trying to better understand the customer archetype who would be attracted to OTC hearing aids and the online buying experience.

Customer Archetypes in Hearing Health Care (Singh & Dhar, 2023)

General Research Question: What are the distinct consumer archetypes that capture motivations behind choosing hearing aid purchase channels—either in-person or online/direct-to-consumer?

What They Did: The study was divided into two sections. The first was an interview phase in which 11 participants, aged 50-plus who had never used hearing aids were asked about their decision-making behaviors. The information extracted from this interview was used to create the second phase, which was a survey. A 28-question survey was conducted for 1,377 adult participants, all over the age of 50. Applying cluster analysis techniques that used five psychological and behavioral factors, physician trust, sociability, comfort buying online, ability to verify sources, and reliance on others, two distinct archetypes emerged: Entrusters and Explorers.

Entrusters tend to be highly independent, comfortable buying online, and consistently verify sources before purchasing. On the other hand, Explorers tend to rely heavily on others during the decision-making process, are less comfortable purchasing online, and are less inclined to verify multiple sources before buying. Despite these differences between the two archetypes, 84% of all respondents preferred in-person care over online/DTC models.

Our Take: Although online may be a convenient way to buy OTC hearing aids, in-person trust and support, provided by an audiologist, is still desired by most individuals, even those who prefer do-it-yourself, online shopping. It is interesting to note that even among those comfortable with online purchasing, traditional in-person pathways remain dominant. Channels like OTC and direct-to-consumer may require additional trust-building and tailored education, especially for Explorers, before becoming viable alternatives.

Willingness to Pay

Many retail businesses rely on willingness to pay studies to help them set prices. By gathering this information from a segment of buyers, they can more carefully match prices for goods and services with what the buyers themselves value. With the advent of OTC hearing aids, we are beginning to see some of the first “willingness to pay” studies emerge in our profession.

Benefit-Cost Analyses of Hearing Aids, Over-the-Counter Hearing Devices, and Hearing Care Services (Jilla et al., 2024)

General Research Question: What are the consumer-perceived benefits and cost-effectiveness of prescription hearing aids, over-the-counter (OTC) hearing devices, and hearing rehabilitation services, as assessed through a willingness-to-pay (WTP) approach and benefit–cost analyses?

What They Did: The researchers used several methods that allowed them to evaluate the value of hearing interventions from the perspective of individuals with hearing aids, focusing on willingness to pay. They conducted a benefit–cost analysis to determine the economic viability of OTCs and hearing rehab services. Their methods included a survey of 70 hearing aid wearers from two independent audiology practices and a chart review of the survey participants. A cost-benefit analysis of these three interventions was conducted.

What They Found: All three hearing interventions—hearing aids, over-the-counter (OTC) hearing devices, and hearing rehabilitation services—demonstrated measurable consumer-perceived benefits. However, the benefit–cost analyses indicated these interventions were cost-effective primarily when out-of-pocket costs remained lower than typical market prices. Specifically, the benefit–cost ratios favored prescription hearing aids even when their costs were as high as $1,530 per device. In contrast, the benefit–cost ratios for OTC devices were less favorable, with a median willingness-to-pay of $0 and a maximum of $500. Hearing rehab services showed a median willingness-to-pay of $250, indicating a moderate perceived value.

Our Take: Willingness to pay studies tell us how customers value various options and provide us with insight into how to price products and services. The results of this study show that customers perceive a difference in prescription hearing aids and OTCs, and perhaps most importantly for audiologists, customers value services. The findings also indicate customers are willing to pay a substantially higher price for prescription hearing aids (~$1500 per device) and a much lower price (~$500) for OTCs. These factors must be taken into consideration when pricing products and services.

Performance-based Research

Comparing Hearing Aid Outcomes in Adults Using Over-the-Counter and Hearing Care Professional Service Delivery Models (Swanepoel et al., 2023)

General Research Purpose: Study the real-world outcomes for OTC products vs. prescriptive hearing aids using a retrospective online survey.

Product: The OTC product was the Lexie Lumen, 16-channel wide dynamic–range compression, with adaptive directionality, and noise reduction (technically, at the time of the study, this was not an “OTC” as these hearing aids were purchased prior to the FDA OTC regulations going live). The prescription hearing aids used by the respondents were from all major manufacturers; the majority 46% were either Phonak or Oticon.

What They Did: In addition to comparing the different products (OTC vs prescription), this study indirectly also compared hearing aid outcomes reported by patients fitted using two different models: the Lexie OTC approach and the conventional hearing care professional (HCP) service delivery. An ecological, cross-sectional survey design was employed. Using the Hearing Tracker database, an online survey was sent to the Hearing Tracker wearers (prescription products), with the same survey sent to the OTC Lexie hearing aid buyers. Self-reported hearing aid benefit and satisfaction were measured with the International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids (IOI-HA).

What They Found: A total of 656 hearing aid wearers completed the survey—406 for the conventional HCP services, and 250 through the OTC. There was no significant difference for overall hearing aid outcomes between the prescription and the HCP and OTC buyers. This finding was controlled for age, gender, duration of hearing loss, duration before hearing aid purchase, self-reported hearing difficulty, and unilateral versus bilateral fitting. The demographics were quite similar for the two groups, although the prescription wearers tended to report more hearing loss: 28% reported that without their hearing aids, they “almost never hear,” which was only reported by 13% of the OTC buyers. More specific IOI-HA findings:

- For the “daily use” domain, wearers of prescription hearing aids reported significantly longer hours of daily use.

- For the “residual activity limitations” domain, OTC hearing aid buyers reported significantly less difficulty hearing in situations where they most wanted to hear better.

Our Take: To some, it might be surprising that outcome measures for OTC hearing aids are equal to a prescription product fitted by a licensed provider. We see two factors that could have impacted this. First, it is reported that the Lexie fitting uses an auto-fit modeled after the NAL-NL2. This would actually give this product an advantage, as most prescriptive hearing aids are fitted using the manufacturer’s proprietary fitting, known to provide less-than-adequate gain. Secondly, the Lexie fitting model includes many post-fitting services, not available with all OTCs.

Comparing Self-Fitting Strategies for Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids: A Crossover Clinical Trial (Knoetze, Manchaiah, et al., 2024)

General Research Question: Compare two different strategies for self-fitting OTC hearing aids: self-adjustment vs. in-situ audiometry.

Product: All participants used the Lexie B2 OTC hearing aid: receiver-in-canal (RIC), on-device volume control, directional technology, and noise reduction. There was a smartphone app that could be customized for individual patients.

What They Did: Twenty-eight participants were pseudo-randomly assigned to 1 of the 2 self-fitting strategies, and in a crossover design, they experienced both interventions for 4 consecutive weeks. The self-adjustment group manually adjusted settings, including overall gain and spectral tilt, while the in-situ audiometry group had an automated fitting, based on in-situ test results.

Outcome measures used: Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB), International Outcome Inventory for Hearing Aids (IOI-HA), speech-in-noise tests (Digits-In-Noise and the QuickSIN), and probe-microphone measurements (REMs). All outcomes were completed at baseline and after the 4-week field trial using each strategy.

What They Found: There was no difference between self-adjustment and in-situ audiometry strategies for overall APHAB benefit, overall IOI-HA satisfaction, speech-in-noise benefit, or probe-microphone measurements. When fitted using self-adjustment, however, participants reported higher satisfaction and longer daily use.

Our Take: The authors suggest that it’s possible that the reported higher satisfaction and longer daily use for the self-fitting strategy might simply be due to the active user involvement in this procedure. We agree. Given that all participants used the same OTC hearing aids, and the resulting probe-mic findings were no different for the two fitting approaches, there is no reason to expect that a group difference would be observed for measures such as the APHAB or the IOI-HA.

Effectiveness of an Over-the-Counter Self-fitting Hearing Aid Compared With an Audiologist-Fitted Hearing Aid: A Randomized Clinical Trial (De Sousa et al., 2023)

General Research Question: To compare the clinical effectiveness of a self-fitting OTC hearing aid (with remote support) to hearing aids fitted by audiologists using a best practices approach.

Product: The Product fitted to all participants was the Lexie Lumen, a behind-the-ear RIC design. The product has 16 channels, wide-dynamic range compression, adaptive directionality, and noise reduction

What They Did: Participants were 66 adults with self-perceived mild to moderate hearing loss, randomly assigned to either the self-fitting or the audiologist-fitted group, and fitted bilaterally. The groups did not differ in age or degree of hearing loss (e.g., PTA). Support and adjustment were provided remotely for the self-fitting group and upon request, for the audiologist-fitted group. Participants in the self-fitting group set up the hearing aids using the supplied instructional material and accompanying smartphone application. For the audiologist-fitted group, the hearing aids were fitted according to the NAL-NL2, verified with probe-mic measures (only to a 65 dB SPL input).

Measures that were conducted at baseline, after a two-week trial, and again following a 4-week home trial were: APHAB, IOI-HA, and speech recognition in noise. The primary speech-in-noise test was the QuickSIN, presented at the patient’s MCL for both unaided and aided.

What They Found: After the 2-week field trial, the self-fitting group had an initial advantage compared with the audiologist-fitted group on the APHAB and the IOI-HA, but not for speech recognition. At the end of the subsequent 4-week trial (total of 6 weeks of hearing aid use), no significant differences were found between the groups on any outcome measures.

Our Take: In general, it has been observed that self-fitting results in less gain than the NAL-NL2; the authors speculate that this could have worked as an advantage for the self-fit during the first two weeks. We would have liked to see the real-ear results for the self-fit group; fitting to “best practice” would include using soft and loud inputs, as well as average, only average was used in this study. Finally, conducting the aided QuickSIN at the level of each patient’s MCL, rather than the conventional fixed-SPL method, tends to wash out the effects of audibility benefit, which could have been present.

Long-Term Outcomes of Self-Fit vs Audiologist-Fit Hearing Aids (De Sousa et al., 2024)

General Research Question: A follow-up to the study conducted by these authors to determine if the earlier findings of DeSousa et al (2024), self-fit equal to audiologist-fit, were also present following several months of hearing aid use.

Product: The Product fitted to all participants was the Lexie Lumen, a behind-the-ear RIC design. The product has 16 channels, wide-dynamic range compression, adaptive directionality, and noise reduction.

What They Did: Follow-up eight months after the original fitting was conducted for 44 (of the original 64) participants in this extension study; 21 in the audiologist-fit group and 23 in the self-fit group (see above, De Sousa et al, 2024 for more details of the original study). Participants completed the APHAB and the IOI-HA—the two self-report inventories conducted in the original study.

What They Found: There was a slight advantage on the IOI-HA for the self-fit group, but in general, these extended data show the same “no difference” finding for the fitting procedure as shown originally. What was interesting, however, was that while APHAB scores (mean values) were essentially unchanged from the 6-week mark, IOI-HA ratings were significantly reduced for both fitting procedures. For example, Satisfaction (5-point scale) dropped from 4.6 to 3.2 for the audiologist-fit, and from 4.7 to 3.5 for the self-fit group.

Our Take: The APHAB asks very specific questions regarding certain listening situations—it seems reasonable that these ratings would not change over time. In fact, if we only look at the Benefit question of the IOI-HA (most similar to the APHAB), that score, for the audiologist-fit group, stayed the same over time, 4.3 (six weeks) vs 4.2 (eight months). We suspect that the large drop in satisfaction is related to factors such as lost aid, dead batteries, loose earpiece, plugged receiver, delayed repairs, etc—factors that cause dissatisfaction unrelated to the fitting itself.

Validation of a Self-Fitting Over-the-Counter Hearing Aid Intervention Compared with a Clinician-Fitted Hearing Aid Intervention: A Within-Subjects Crossover Design Using the Same Device (Baltzell et al., 2025)

General Research Question: In a cross-over design, to compare the same self-fitting OTC hearing aids when the patient independently conducted the self-fitting vs. when they were assisted by an audiologist.

Product: All participants were fitted bilaterally with Concha Sol self-fitting OTC hearing aids, a product of Concha Labs. Concha Sol hearing aids are receiver-in-canal with 16-channel wide-dynamic range compression.

What They Did: The 21 participants were assigned to either a clinician-fitting or self-fitting group. The mean age was 66, 17 were new wearers, and PTA-four frequency was 37 dB. For clinician-fit, the audiologist generated prescription targets provided by the manufacturer, based on the participant's audiogram. The WDRC was manually adjusted if participants expressed immediate sound quality complaints. For the self-fitting, wearers began by listening to a series of narrow-band noises, delivered through the hearing aid receiver, and adjusting a slider until the sound was just audible. Listening to synthesized female speech stimuli from their mobile phones, several A/B comparisons were then made, which resulted in gain adjustments.

The QuickSIN (target speech at 70 dBA SPL) and the APHAB were administered before and after the 2-week field trial.

What They Found: The gain adjustment procedure used by the audiologists resulted in somewhat more gain for those with greater hearing loss; resulting gain values were similar for the milder losses. For the APHAB, aided was better than unaided for all conditions. The only significant subscale difference between clinician-fitted and self-fitted was for background noise—self-fitted better than clinician-fitted (~10% fewer problems for self-fitting). QuickSIN scores for the clinician-fitted procedure were not significantly different from the unaided control. There was, however, a statistically significant improvement in QuickSIN scores for the self-fitted approach relative to both the unaided control and to the clinician-fitted intervention (e.g., 1.7 dB SNR improvement for self-fitted).

Our Take: The title of this article is somewhat misleading, as the “clinician fit” approach was simply using adjustments from the manufacturer’s software. It was not what most would consider a best-practice clinician fit: output adjusted to a validated prescription target, verified with probe-mic measures. The small but significant advantage of the self-fit for the QuickSIN is somewhat puzzling. If indeed the clinician-fit intervention had more gain (initially it did, but it doesn’t appear that user-adjusted gain was measured), perhaps for a 70 dB SPL input (level used for aided testing), the increased gain served as a negative, rather than a positive—depending on how the input compression and MPO was adjusted, this input level could have resulted in the output being uncomfortably loud for some listeners.

Gain Analysis of Self-Fitting Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids: A Comparative and Longitudinal Analysis (Knoetze, Manchaiah, Cormier, et al., 2025)

General Research Question: To determine the gain provided using a self-fitting OTC hearing aid approach vs. NAL-NL2 targets for different OTC devices. Additionally, to examine potential changes in gain over time.

Product: The first experiment used six different self-fitting OTC products: HP Hearing PRO, Jabra Enhance Plus, Lexie B2, Lexie Lumen, Sontro, and Sony CRE-C10—using a cross-sectional design and REMs to measure gain after self-fitting. The second experiment used three of these: Lexie B2, Lexie Lumen, and the Sontro.

What They Did: Participants were a total of 43 adults; 13 to 15 wearers per device, with each participant fitting two devices; 5 reported previous hearing aid use. Mean 4-frequency PTA was 36.5 dB HL. Participants self-fitted their hearing aids; real-ear measures were conducted after each fitting for average, soft, and loud speech inputs (65, 55, and 75 dB SPL)

Experiment 2 consisted of 15 participants: five Sontro, six used Lexie B2, and four used Lexie Lumen. Hearing aid use-gain was measured via probe-mic measures within five days of self-fitting and at four additional points over the first year of use.

What They Found: Self-fit OTC products resulted in a gain that was ~10 dB below NAL-NL2 targets. Differences between NAL-NL2 targets and self-fit gain did not differ significantly between devices. In experiment #2, over the first year of hearing aid use, there were no significant changes in gain for any input level.

Our Take: These data support what is generally known about the self-fitting approach—the resulting gain is significantly below the NAL-NL2, enough so that a reduction in speech understanding would be expected. The findings from Experiment #2, interestingly, are similar to the work of Mueller et al. (2008), who found that when participants used trainable hearing aids, initially fitted to 6 dB below NAL targets, they did not “train up,” but continued to remain ~6 dB below NAL targets.

An Over-The-Counter (OTC) Hearing Aid Option for People with Self-Perceived Mild-to-Moderate Hearing Loss: Nuance Audio™ Hearing Aid Glasses (Harel-Arbeli & Beck, 2025)

General Research Question: Compare aided Nuance hearing aids to unaided, determine real-world benefit using self-assessment scales, and compare to prescription hearing aids for speech-in-noise testing.

Product: Nuance Audio Hearing Glasses. The glasses frames have six microphones and a sound processor, and incorporate noise reduction and beamforming algorithms, with user control options. The glasses transmit sound to each ear through tiny speakers embedded in the frames; there is no earpiece.

What They Did: This article reviews three different studies with the Nuance Audio product:

- Study #1: Compared speech-in-noise recognition (SRT50) for the Nuance to two prescriptive hearing aids for 19 individuals, who were experienced hearing aid wearers. The speech test was the Hebrew version of the Matrix test; target sentences were delivered from 0 degree azimuth, and competing speech (speech-spectrum noise) was delivered from 90 and 270 degree azimuths. The prescriptive products were programmed to the manufacturer’s proprietary “first fit.” The Nuance product was optimized for speech understanding by an audiologist.

- Study #2: Participants were 43 individuals (13 experienced wearers); four-frequency PTA of 38 dB. All were fitted bilaterally with Nuance, adjusted to the most comfortable preset. The Hebrew Matrix speech-in-noise test was conducted for unaided and aided. Additional measures were ratings for real-world listening situations and a report of listening effort.

- Study #3: Participants were 23 adults with self-perceived mild-to-moderate sensorineural hearing loss, who were fitted with the Nuance hearing aid for 14 days. At the end of the trial period, they completed the IOI-HA self-assessment scale; the IOI-HA findings were then compared to the norms of the IOI-HA.

What They Found:

- Study #1: Compared to unaided, the two prescription hearing aids improved the SRT50 by ~2 dB; the Nuance improvement from unaided was ~4 dB. Statistical analysis revealed that a) each of the three aided conditions was significantly different from the unaided condition, b) the prescription products were not different from each other, and c) the Nuance was significantly better than both prescriptive products.

- Study #2: Similar to Study #1, the speech-in-noise testing revealed a 3.5 dB SRT50 improvement, aided vs. unaided. The Nuance product was determined to be significantly better than “neutral” across all three subjective “pseudo real-life” situations. The findings for listening effort were not reported.

- Study #3: When comparing IOI-HA ratings from the participants to IOI-HA norms, results showed no significant difference in performance for benefit and quality of life (items 2 and 7). For the other five items, however, (1, 3, 4, 5, 6), rating using Nuance scored significantly better than the published IOI-HA norms.

Our Take: In Study #1, it’s important to note that the prescription hearing aids were fitted to the manufacturer’s proprietary fittings. It is well known that these proprietary algorithms provide considerably less gain than normally recommended. It is very possible, if not probable, therefore, that the SNR advantage for Nuance is simply due to more audibility provided by this product (the authors do not state the presentation level of the Matrix sentences). In Study #2, because again the presentation level is not stated, we don’t know if the 3.5 dB improvement from unaided is due to audibility or signal processing.

Subjective Wearer Results with Over-the-Counter, Self-Fitted CIC Hearing Aids (Branda et al., 2025)

General Research Question: To determine if OTC CIC products, using the self-fitting approach, provided benefit (compared to unaided) as measured by self-report inventories.

Product: CIC style, with sleeves available in four sizes for coupling to the ear. Wireless connectivity between devices is provided for alignment in sound environment classification, volume settings, noise reduction characteristics, and directional processing. Devices were able to receive a high-frequency acoustic signal from cell phones, which was used for programming.

What They Did: Participants were twenty-six adults (Female: 8, Male: 18) aged 34-82 years (mean age 62; 22 new hearing aid wearers) with mild-moderate bilateral, sensorineural hearing loss. All fittings were bilateral. Using the fitting app, tones were presented via the hearing aids, and a hearing profile was established. Based on the resulting profile, an initial amplification setting was obtained. Participants were able to adjust gain settings via the app.

Prior to the two-week field trial, the participants completed both the APHAB and the SSQ12 (for unaided listening). These two self-report inventories were then completed again following the trial for aided listening.

What They Found: For the APHAB, aided performance, relative to unaided, was significantly better for listening in quiet, in noise, and in reverberation. For the SSQ12, a significant aided improvement was observed for the 5 speech understanding items (mean of 4.4 vs. 6.2 for aided). No significant improvement was noted for the Spatial items.

Our Take: The aided benefit for both the APHAB and SSQ12 is less than most studies with prescription hearing aids, but important to remember that these participants had milder hearing loss; the mean PTA (500, 1000, 2000 Hz) of only ~24 dB. Also, two weeks is rather brief for a field study for new hearing aid wearers. It would have been interesting to see the real-ear gain settings for the participants following the field trial.

Evaluation of Communication Outcomes With Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids (Szatkowski & Souza, 2025)

General Research Question: Evaluate the benefits of OTC hearing aids, fit to the manufacturer’s pre-sets, for conversation efficiency and auditory recall following speech recognition.

Product: The FDA-approved OTC hearing aids used in this experiment (brand not disclosed) were a receiver-in-the-ear style coupled to a flexible dome-shaped earpiece. The devices contained four preset programs changeable by a pushbutton, mild and moderate, indoor noise, and outdoor noise. Of the 30 participants in this study, 17 were fitted with the mild program as their default, and 13 were fitted with the moderate program.

What They Did: Participants were fitted with preprogrammed OTC hearing aids using the default program with the best match to target for each listener.

- The DiapixUK task was used to measure conversation efficiency between participants and their familiar communication partners and was calculated as the sum of time during active conversation for each difference identified during the task. Efficiency time was compared between two hearing aid conditions: unaided and aided (participant-assigned default program of mild or moderate).

- Auditory recall was evaluated following speech recognition-in-noise to low- and high-context sentence presentations in 5- and 10-dB SNR. Speech recognition and auditory recall were evaluated across three hearing aid conditions: unaided, aided with the participant-assigned OTC default program, and aided with the OTC noise reduction program.

What They Found: No significant improvement in conversation efficiency with hearing aid use was observed when compared with the unaided condition. There was also no significant benefit (compared to unaided) for auditory recall with the OTC instruments using either of the two programs; the best median scores were with the noise-reduction program. Sentence recognition scores were near the ceiling in the unaided condition.

Our Take: As the authors point out, the preset outputs for the OTC products fell below NAL-NL2 targets above 2000 Hz, making it difficult to determine if the absence of significant benefit was simply due to ineffective audibility or the signal processing of the products. Given that the outcome measures employed in this research are not commonly used, we would have liked to have seen comparative data for prescription hearing aids fitted to NAL-NL2 targets. Would these data have shown a significant benefit?

Usability and Performance of Self-Fitting Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids (Knoetze, Manchaiah, & Swanepoel, 2025)

General Research Question: Examined if there was a significant difference in the usability and performance of six different OTC products.

Products: The six commercially available products tested were: HP Hearing PRO, Jabra Enhance Plus, Lexie B2, Lexie Lumen, Soundwave Sontro, and Sony CRE-C10.

What They Did: In a cross-sectional design, participants, 43 adults with self-perceived mild-to-moderate hearing difficulties, were randomly assigned to two of six OTC self-fitting hearing aids. Usability was assessed based on the fitting time, hearing aid skills and knowledge, self-reported ease of the self-fitting process, and a post-fitting usability questionnaire. Measures of performance were evaluated using sound quality scaling and two speech-in-noise tests.

What They Found:

- Fitting time ranged from 14.4 to 27.1 min: Lexie Lumen requiring the longest (27.1 min) and the HP Hearing PRO the shortest (14.4 min).

- For skills and knowledge, Soundwave Sontro achieved the highest score (8.9/10) and HP Hearing PRO the lowest score (6.8/10).

- Self-reported ease of fitting and the post-fitting usability did not differ among products.

- Overall sound quality and clarity ratings were significantly different, with Lexie B2 receiving the highest rating (8.1/10 and 7.5/10) and HP Hearing PRO receiving the lowest rating (6.3/10 and 5.1/10).

- Speech-in-noise benefit did not differ significantly among products.

Our Take: Given that there was a fairly large difference in the clarity ratings, one might think that there also would have been a difference in the speech-in-noise findings, which there wasn’t. There is a simple explanation, however. The authors report conducting both speech tests (DIN and QuickSIN) for unaided and aided at 70 dB HL, which would be ~83 SPL for most soundfield set-ups. That’s right, 83 dB SPL! We would not expect a SIN improvement at this high intensity, as audibility would have been maximized in the unaided, and moreover, this aided level probably exceeded the LDL of some of the participants, and it’s possible that some or all of the products would have been driven to their MPO, which could equalize SNR differences.

Hearing Aid Service Models, Technology, and Patient Outcomes: A Randomized Clinical Trial (Wu et al., 2025)

General Research Question: Do higher levels of hearing aid technology, and/or associated fitting services, lead to better patient outcomes?

Product: Unlike most research reviewed here, the product(s) were not OTCs, but rather entry-level and premier behind-the-ear prescription hearing aids, but from the same manufacturer (unnamed). Both models were used in two roles: as prescription hearing aids (when fitted by an audiologist) and to simulate preset-based OTC hearing aids in two other experimental intervention groups.

What They Did: This was a randomized clinical trial conducted from February 2019 to December 2023 and included 245 adults older than 55 years with mild to moderate hearing loss and no previous hearing aid experience, randomly assigned to 1 of 6 parallel groups, representing the 3 service models and the 2 technology levels.

The 3 service models:

- AUD, in which audiologists fitted prescription HAs following best practices.

- OTC+, in which audiologists provided limited services for (simulated) OTC hearing aids.

- OTC, in which participants independently used (simulated) OTC hearing aids.

The primary outcome measure was the Glasgow Hearing Aid Benefit Profile (GHABP), which was administered using ecological momentary assessment (EMA), beginning before the hearing aid fittings and throughout the seventh week of hearing aid use.

What They Found: The EMA-GHABP global scores following the hearing aid field trial were significantly better for the AUD delivery system than either the OTC+ or OTC; the OTC+ and OTC findings, however, were still considered a “positive outcome.” The effect of technology level and the interaction between service model and technology level were not significant. The entry-level vs. premier technology was not significantly different for any of the three treatment conditions.

Our Take: The premier vs. entry-level no-difference finding is not unique, and has been found in other studies, going back to the work of Robyn Cox a decade ago. Moreover, it is difficult to apply these findings to today’s clinical practice—what was considered “premier” several years ago might be mid-level or entry-level today. And, new “premier” technology is introduced each year. Perhaps the most interesting finding from this study relates to the presets that were selected—unlike most other OTC studies that we recall, nearly 50% of the “OTC group” selected the preset with the greatest high frequency gain—resulting in this group having as-worn average REARs (for average-level inputs) equal to the NAL-NL2 prescriptive targets. To add to the interest level, the AUD group, who were fitted to the NAL-NL2 prescription by an audiologist using probe-mic measures, had average REARs falling below NAL-NL2 targets in the 3000-4000 Hz region.

In Closing

In this Volume of Research Quick Takes, we’ve reviewed a group of studies, all from the past few years, which in one way or another have looked at the impact of the entrance of OTC products to the hearing aid market. We organized these into “consumer-based” and “performance-based,” although there might be a slight overlap in some cases. While our review included 20 or so different published articles (nearly all peer-reviewed), there are at least another 20-30 that we didn’t mention. We certainly didn’t “cherry-pick” articles that might lead to any preconceived notions, beliefs, or biases that we might have, but rather, simply gathered a group of what we believe are a fairly representative sample of what has been published over the last couple of years. Here are a few summary statements.

Consumer-based Studies

- The profile of OTC buyers appears to be different than prescription hearing aid buyers. For example, they are younger and more socially active. These differences can be used to determine how products are marketed.

- Willingness-to-pay data demonstrates that consumers recognize the difference between OTC and prescription hearing aids, and also the DTC vs. audiologist-driven service model

- Although many consumers might recognize these differences, the average consumer has difficulty comprehending many of the health-related details on current OTC labeling. Additionally, it appears that a large number of individuals either overestimate or underestimate their hearing loss, which could lead to improper self-selection of OTC. That is, some individuals with worse than a moderate hearing loss think they are proper OTC candidates, while others with mild hearing loss believe that OTC is not appropriate for their hearing loss. All told, the studies we reviewed here suggest that OTC manufacturers must improve their product labeling and use questionnaires to guide the self-selection process more accurately.

Performance-based Studies

Many studies had design qualities that made it difficult to interpret the validity of the findings (see the “Our Take” section of each review for details). With that said:

- In general, when prescription hearing aids were compared head-to-head with OTC products, differences were small.

- Some studies using self-report outcome measures had findings for OTCs that equaled or exceeded the norms established with prescription fittings.

- One study found that an OTC product was superior to prescription products for speech-in-noise understanding. On the other hand, one study found that outcomes with OTCs were no better than unaided.

- In general, the gain obtained using the pre-sets for the OTC products tended to be below a well-fitted prescription product, which can then impact long-term outcomes. Patients do not appear to increase use-gain over time.

The Role of the Audiologist

Finally, it is also important to mention what we believe can be the role of the audiologist in the existing marketplace, where both OTC/prescription and in-person/DTC are all available. Here are four somewhat different options:

- Serve as “quality control gate-keepers”: Apply knowledge of what a high-fidelity hearing aid provides and how to assess this in the clinic using Best Practice.

- “OTC+ model” of care: Limited service provided with the sale of OTC devices.

- “Help me get the most from my OTC” service model: Fine-tune and counsel existing OTC wearers.

- “Upgrade” service model: Know when an upgrade to prescription products is in the best interest of the customer. Recall the MarkeTrak 2025 finding that we reported, that OTC owners who plan to purchase new hearing aids in the next few years, over half think that they will buy in-person from an HCP.

References

Bailey, A. (2025). Full list of OTC hearing aids in 2025. Hearing Tracker. https://www.hearingtracker.com/otc-hearing-aids/full-list

Baltzell, L. S., Kokkinakis, K., Li, A., Yellamsetty, A., Teece, K., & Nelson, P. B. (2025). Validation of a self-fitting over-the-counter hearing aid intervention compared with a clinician-fitted hearing aid intervention: A within-subjects crossover design using the same device. Trends in Hearing, 29.

Branda, E., Phelan, J., Littmann, V., Lelic, D., & Jorgensen, L. (2025). Subjective wearer results with over-the-counter, self-fitted cic hearing aids. AudiologyOnline, Article 29238. Available at www.audiologyonline.com

Convery, E., Keidser, G., Hickson, L., & Meyer, C. (2019). Factors associated with successful setup of a self-fitting hearing aid and the need for personalized support. Ear and Hearing, 40(4), 794–804.

Conway, K., Knoetze, M., Swanepoel, D. W., Nassiri, A., Sharma, A., & Manchaiah, V. (2025). Marketing practices and information quality for OTC hearing aids on Amazon.com. Manuscript submitted for publication.

De Sousa, K., Manchaiah, V., Moore, D., Graham, M., & Swanepoel, D. (2024). Long-term outcomes of self-fit vs audiologist-fit hearing aids. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery, 150(9), 765–771.

De Sousa, K. C., Manchaiah, V., Moore, D. R., Graham, M. A., & Swanepoel, W. (2023). Effectiveness of an over-the-counter self-fitting hearing aid compared with an audiologist-fitted hearing aid: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery, 149(6), 522–530.

Dobyan, B. (2024). 20Q: Interpreting the hearing health landscape through MarkeTrak - from insight to impact. AudiologyOnline, Article 29350.

Hamburger, A., Whitehead, R., & Michaelides, E. (2025). Misjudgments of hearing loss and its implications for over-the-counter hearing aids. OTO Open, 9(2), e70101.

Harel-Arbeli, T., & Beck, D. L. (2025). An over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aid option for people with self-perceived mild-to-moderate hearing loss: Nuance Audio™ hearing aid glasses. Journal of Otolaryngology and ENT Research, 17(1), 9–14.

Humes, L. E. (2024). Demographic and audiological characteristics of candidates for over-the-counter hearing aids in the United States. Ear and Hearing, 45(5), 1296–1312.

Humes, L. E., Rogers, S. E., Quigley, T. M., Main, A. K., Kinney, D. L., & Herring, C. (2017). The effects of service-delivery model and purchase price on hearing-aid outcomes in older adults: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. American Journal of Audiology, 26(1), 53–79.

Knoetze, M., Beukes, E., Manchaiah, V., Oosthuizen, I., & Swanepoel, W. (2024). Reasons for hearing aid uptake in the United States: A qualitative analysis of open-text responses from a large-scale survey of user perspectives. International Journal of Audiology, 63(12), 975–986.

Knoetze, M., Manchaiah, V., Cormier, K., Schimmel, C., Sharma, S., & Swanepoel, D. (2025). Gain analysis of self-fitting over-the-counter hearing aids: A comparative and longitudinal analysis. Auditory Research, 15(1), 17.

Knoetze, M., Manchaiah, V., De Sousa, K., Moore, D., & Swanepoel, D. (2024). Comparing self-fitting strategies for over-the-counter hearing aids: A crossover clinical trial. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery, 150(9), 784–791.

Knoetze, M., Manchaiah, V., & Swanepoel, D. (2025). Usability and performance of self-fitting over-the-counter hearing aids. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 36(1), 23–36.

Maidment, D. W., Nakano, K., Bennett, R. J., Goodwin, M. V., & Ferguson, M. A. (2025). What's in a name? A systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the effectiveness of non-medical amplification devices in adults with mild and moderate hearing losses. International Journal of Audiology, 64(2), 111–120.

Manchaiah, V., Amlani, A. M., Bricker, C. M., Whitfield, C. T., & Ratinaud, P. (2019). Benefits and shortcomings of direct-to-consumer hearing devices: Analysis of large secondary data generated from Amazon customer reviews. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 62(5), 1506–1516.

McPherson, B., & Wong, E. T. (2005). Effectiveness of an affordable hearing aid with elderly persons. Disability and Rehabilitation, 27(11), 601–609.

Mueller, H. G., Hornsby, B., & Weber, J. (2008). Using trainable hearing aids to examine real-world preferred gain. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 19(10), 758–773.

Powers, T. A. (2022). 20Q: OTC hearing aids—They’ve arrived! AudiologyOnline. https://www.audiologyonline.com

Singh, J., Johnston, E., & Dhar, S. (2025). Comprehension and use of the over-the-counter hearing aid product information label. Seminars in Hearing, 46(1), 53–64.

Swanepoel, D. W., Oosthuizen, I., Graham, M. A., & Manchaiah, V. (2023). Comparing hearing aid outcomes in adults using over-the-counter and hearing care professional service delivery models. American Journal of Audiology, 32(1), 314–322.

Szatkowski, G., & Souza, P. (2025). Evaluation of communication outcomes with over-the-counter hearing aids. Ear and Hearing, 46(3), 653–672.

Taylor, B. & Mueller, H. G. (2023). Research QuickTakes Volume 5: OTC hearing aids—pros, cons, and implementation strategies. AudiologyOnline, Article 28695. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com

Wu, Yu-Hsiang, Stangl, E., Branscome, K., Oleson, J., & Ricketts, T. (2025). Hearing aid service models, technology, and patient outcomes: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery, 151(7), 684–692.

Citation

Mueller, H. G., & Taylor, B. Research Quick Takes, volume 10: An update on OTC hearing aids. AudiologyOnline, Article 29477. Available at www.audiologyonline.com