Question

What is the role of the video head impulse test (vHIT) in diagnosing and managing acute unilateral vestibulopathy?

Answer

Acute unilateral vestibulopathy (AUV) is a clinical condition characterized by long-lasting vertigo with nausea and vomiting, gait instability, and a tendency to fall toward the affected side, without associated cochlear or central nervous system symptoms and signs (Baloh, 2003).

Currently, the results of ocular vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (oVEMPs) and cervical vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (cVEMPs) can be combined with the results of the video head impulse test (vHIT) and caloric vestibular test (CT) to obtain a picture regarding the state of the peripheral vestibular function of each sense organ as well of each branch of the vestibular nerve (VN). The CT and the vHIT permit the examination of the horizontal semicircular canal (HC) function with a low (0.03 Hz) and high (5 – 7 Hz) frequency stimulus range; in turn, both tests provide information about the function of the superior VN. vHIT devices also enable testing of the anterior semicircular canal (AC) and the posterior semi-circular canal (PC); a normal vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) gain in the PC suggests that the function of the inferior VN is preserved. Saccular and inferior VN function can be studied using cVEMPs; utricular and superior VN function with oVEMPs (Curthoys, 2012).

Deeper understanding of AUV, according to instrumental analysis, could improve our approach to this lesion. In particular, a better definition of its lesion patterns may benefit medical and rehabilitative treatment.

vHIT constitutes a method quantifying the high velocity semicircular canal function as VOR gain (Chen and Halmagyi, 2020). VOR gain is a frequently used physiological measure of VOR function, able to differentiate patients with vestibular hypofunction from patients without it. A VOR gain lower than 0.68 has been proposed as cut-point between normal and abnormally low VOR gain (Halmagyi et al, 2017). The relative right-left asymmetry VOR gain ratio (AI%), automatically determined by some vHIT software, expresses the asymmetrical response to head rotation. A pathologically increased AI% is described in peripheral AUV in respect to other acute vestibular syndromes (Chen). To date, some vHIT softwares also provide analysis of the compensatory catch-up saccades (CSs) that occur to compensate for a deficient VOR and the resulting gaze-instability, offering new interesting perspectives (Halmagyi et al, 2017; Chen and Halmagyi, 2020).

Our experience regards 51 patients suffering from AUV using vHIT, caloric test (CT) and both cVemps and oVemps. Most patients demonstrated a pathological high-velocity HC VOR gain (98%) and CP (91%). Some dissociated findings were found between CVT and HC vHIT (5 cases): some patients presented a normal caloric response despite pathological HC VOR gain; conversely, no patients exhibited a pathological caloric response despite a normal HC vHIT. The second most affected receptor was the AC (83%), followed by the utricle (72%), and PC (45%), while the saccule was the least damaged (44%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Role of video Head Impulse test in two main vestibular pathology: Acute Unilateral VestibulInvolvement of vestibular receptors in our series of patients affected with AUV. AC: anterior canal; HC, horizontal canal; CT: caloric test. In yellow receptors innervated by the inferior vestibular nerve. In blue the receptors innervated by the superior vestibular nerve.

Nineteen of 59 patients exhibited involvement of all five vestibular end organs (32%). Thirteen of 59 patients exhibited an impairment of HC, AC, and utricle (22%); among whom, one had a normal lowvelocity and a pathological high-velocity HC function. The remaining patients exhibited a selective receptor injury (46%). Among these, 13 patients exhibited an impairment of the receptors innervated by both the upper and lower branch of the VN (22%), while 14 only by its superior division (24%). AUV patients with exclusive damage to the saccule and/or to the PC were not identified. These results are reported in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Results of the instrumental assessment in patients suffering from AUV according to vestibular nerve (VN) partition. I: inferior. S: superior.

Thirteen patients exhibited selective canal involvement (22%) and only one exhibited selective otolith involvement (1%).

Our data suggest that most patients with AUV exhibited total endorgan damage; this finding can be related to damage a to the entire labyrinth or, more probably, to a vestibular neuritis involving both divisions of the VN. The second most frequent pattern we found was that it was more likely to be related to a superior vestibular neuritis. We did not identify cases of AUV that exhibited isolated dysfunction of the PC and/or the saccule. The remaining patients experienced selective damage to the vestibular end-organs, which can be explained by a partial nerve lesion, as previously suggested by other Authors who described isolated utricular or saccular nerve rather than isolated ampullary nerve dysfunctions (Magliulo et al, 2012; Manzari et al 2014). However, these findings are more likely to be consistent with an intralabyrinthine lesion pattern (Hegemann and Wenzel, 2017).

Interestingly, five patients exhibited dissociation in HC function studied using the CT (normal HC response) rather than the vHIT (pathological HC response), enabling the definition a high-velocity dysfunction of the HC.

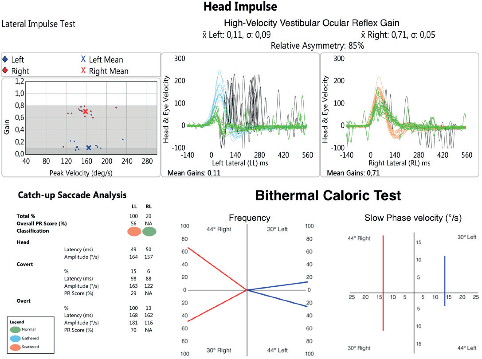

Figure 3. Patient suffering from AUV. vHIT (A) showing an abnormal VOR gain for left HC, while normal values are reported the utricular and saccular maculae.

These results could reflect selective damage to vestibular type 1 hair cells in a limited number of patients, opposite to what has already been well described in Menière’s disease (Cerchiai et al, 2016). Nevertheless, our findings agree with previous reports that found the vHIT to be more reliable than CT in AUV due to higher sensitivity (Magliulo et al, 2012).

What we have reported further emphasizes the need to study HC function using both the CT and the vHIT. These two tests do not provide redundant or overlapping information and must be considered to be complementary in studying HC function.

A deeper understanding of AUV could be achieved through a rigorous definition of its patterns. To do this, a complete instrumental assessment, including in particular vHIT, should be used. Slightly more than half of AUV cases appeared to be related to a nerve lesion, while the remaining cases were more likely to be consistent with an intralabyrinthine lesion model. Patterns more consistent with a vestibular neuritis appear to be related to a poorer outcome and, thus, require a vestibular rehabilitation (VR) program (Navari and Casani, 2020).

Patients who experience residual symptoms after AUV can be approached with VR programs; the use of VR has increased exponentially over the last 25 years and has proved its efficacy both in reducing the symptoms and in improving posture, gait, gaze stabilization and quality of life (Herdman, 2013). However, clear indications of VR still do not exist. The relationship between clinical aspects, vestibulometric parameters and clinical recovery after AUV has generated great interest over the years. Authors have tried to correlate the prognosis with the results of caloric test (Karsarkas and Outerbridge, 1981), posturography (Strupp et al, 1998), Vestibular Evoked Miogenic Potentials (Adamec et al, 2014), rotating chair test (Allum and Honegger, 2013), and vHIT (Patel et al, 2016). Despite the constant improvement of vestibulometric techniques, there is still no agreement about their utility in predicting the realization of a good vestibular compensation: patients who do not complain about dizziness can have an abnormal vestibulometric pattern and vice versa. The employment of the latest release of vHIT firmware, allowing analysis of the compensatory catch-up saccades, seems to offer new interesting perspectives. The introduction of the vHIT has improved the sensitivity of the technique and has overcome the limits of the manually performed head impulse tests both in VOR gain and CSs analysis (Weber et al, 2008); furthermore, vHIT proved to be of interest to clinicians in defining instrumental hallmarks of important vestibular disorders, as Menière’s Disease (Cerchiai et al, 2016).

However, literature shows contrasting results about the relationship between vHIT findings and other parameters like age, canal paresis (CP) and the symptoms scale (Dizziness Handicap Inventory, DHI).

In order to evaluate the role of vHIT in predicting the outcome of AUV, we studied two groups of patients, the first with a good clinic recovery after AUV and the other suffering from residual symptoms needing a treatment with VR. All the patients were analyzed after 4 weeks from the onset of the acute symptomatology. Analyzing the relationship between VOR gain and the presence of compensatory saccades (CSs), we found that lower values of VOR gain are associated with higher prevalence of overt saccades (O-CSs); a decrease of VOR gain causes also a small decrease of O-CSs latency and a significant increase of O-CSs amplitude. Conversely, the presence of covert saccades (C-CSs) seems to be independent of the VOR gain. Both the vHIT and caloric test measure the unilateral VOR but at high (5-7 Hz stimulus) and low (0.003 Hz stimulus) temporal frequencies respectively. Our analysis showed a negative correlation between VOR gain and CP: although most AUVs should cause both low- and high-velocity VOR hypofunction, literature shows different results. On one hand CP and VOR gain appear to be correlated (Bartolomeo et al, 2014; Allum et al, 2016). On the other hand, vestibular compensation seems frequency-dependent (with high-velocity VOR gain recovering more slowly than CP) (Zellhuber et al, 2014).

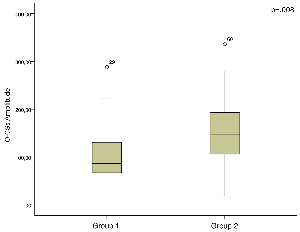

The DHI constitutes one of the most commonly used measures based on patient’ s reported outcome and represents the main symptom scale we use during the follow-up of AUV patients (Fong et al, 2015). The analysis of correlations show that the DHI score increases (meaning a progressively higher level of disability) as the following conditions occur: increase in prevalence of O-CSs, increase in amplitude of O-CSs, and decrease of high-velocity VOR gain (Figure 4).

Figure 4. In the patients with spontaneous recovery after AUV (a) the amplitude of O-CSs is significantly lower in respect to the group of patients who needed VR.

Conversely, neither a higher CP rate nor a higher prevalence of C-CSs is relevant to worsening symptoms. Our results indicate that a deficient high-velocity VOR gain is most likely to cause or determine a worse prognosis, (this is also reflected on higher DHI scores) (Figure 5). Conversely, the degree of CP after 4 weeks from the onset is irrelevant for clinical recovery. The presence of O-CSs (generally also with greater amplitude) negatively affect the outcome as well, being associated with higher DHI scores. Patients with lower VOR gain and high prevalence of O-CSs (also greater in amplitude on vHIT) after 4 weeks from the onset of an AUV are more likely to develop chronic dizziness, unsteadiness and spatial disorientation; alterations in CP and C-CSs do not affect the clinical outcome. This could be of great interest to clinicians in identifying patients who are more likely to need a VR program (Cerchiai et al, 2016).

Figure 5. A typical vestibulometric pattern in a patient with poor recovery after AUV and needing VR. Note the high number and amplitude of O-CSs and the low value of HF-VOR on the left side (A). On the other hand, CT shows a mild reduction of slow phase velocity of the caloric-induced nystagmus (B).

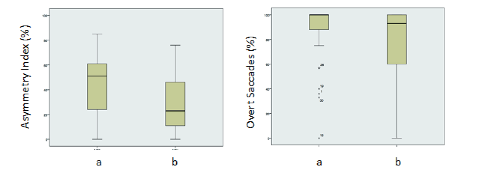

Another main application of vHIT in patients suffering from AUV undergoing VR is represented by the possibility offered by vHIT to evaluate the outcome in this category of patients. We tried to investigate the vHIT as a useful outcome measure of treatment during VR in patients with chronic symptoms after AUV. Since our experience confirmed the usefulness of VR in this category of patients, our data seems to relate the efficacy of the treatment with modification in VOR gain values and CSs features. . In particular, an increased VOR gain in association with a reduction in number and amplitude of overt CSs would be able to predict a good outcome after VR; on the other hand, the analysis of covert CSs seems to be of no interest for the same purpose. Gaze stabilization exercises improve visual acuity during head rotation, and changes in VOR gain and CSs parameters – such as those we identified in our study - can contribute to this recovery, providing some useful information in order to define the outcome after VR. Interestingly, the findings observed in our study perfectly agree with the previous report about the analysis of CSs in AUV patients (Cerchiai et al, 2018). The parameters established to reflect incomplete spontaneous recovery (lower high-velocity VOR gain, increased AI, increased overt CSs number and amplitude) are the same found to be significantly improved after VR in this study, defining a good clinical outcome (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Differences in terms of Asymmetry Index (left) and overt saccades (right) before (a) and after (b) VR.

Therefore, the analysis of VOR gain and prevalence and amplitude of overt CSs seems to provide useful information about the recovery in AUV patients in spite of covert CSs. Overt CSs average latency was augmented but not statistically different after VR in our study. The data we report could be of great interest in order to better assess the patient during VR; vHIT might eventually be combined either with posturography or with questionnaires already used as outcome measures. In particular, the lack of changes in the above mentioned vHIT parameters could provide information about gaze- stabilization improvement promoted by VR. VR is a valid approach for patients with chronic symptoms after AUV. The vHIT seems to be useful for defining the efficacy of the treatment. In particular, an increased VOR gain and a reduction in number and amplitude of overt CSs are likely to predict a good outcome after VR. These findings constitute objective measures of outcome that could be of great interest for clinicians in order to evaluate the improvement of patients during VR (Navari et al, 2018).

References:

- Adamec I, Skoric ́ MK, Handzic ́ J, et al. The role of cervical and ocular vestibular-evoked myogenic potentials in the follow-up of vestibular neuritis. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2014;45:129-136.

- Allum JH, Cleworth T, Honegger F. Recovery of vestibulo- ocular reflex symmetry after an acute unilateral peripheral vestibular deficit: time course and correlation with canal paresis. Otol Neurotol. 2016;37:772-780.

- Allum JH, Honegger F. Relation between head impulse tests, rotating chair tests, and stance and gait posturography after an acute unilateral peripheral vestibular deficit. Otol Neurotol. 2013;34:980-989.

- Baloh RW. Clinical practice. Vestibular neuritis. N Engl J Med 2003;13:1027-1032.

- Bartolomeo M, Biboulet R, Pierre G, Mondain M, et al. Value of the video head impulse test in assessing vestibular deficits following vestibular neuritis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271:681-688.

- Cerchiai N, Navari E, Dallan I, Sellari-Franceschini S, Casani AP. Assessment of vestibulo-oculomotor reflex in Meniere’s disease: Defining an instrumental profile. Otol Neurotol 2016;37:380-384.

- Cerchiai N, Navari E, Sellari-Franceschini S, Re C, Casani AP. Predicting the outcome after acute unilateral vestibulopathy: Analysis of vestibulo-ocular reflex gain and catch-up saccades. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2018;158:527–533.

- Chen L, Halmagyi GM. Video Head Impulse Testing: from bench to bedside. Semin Neurol 2020;40:5-17.

- Curthoys IS. The interpretation of clinical tests of peripheral vestibular function. Laryngoscope 2012;122:1342-1352.

- Fong E, Li C, Aslakson R, Agrawal Y. Systematic review of patientreported outcome measures in clinical vestibular research. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015;96:357-365.

- Halmagyi GM, Chen L, MacDougall HG, et al. The Video Head Impulse Test. Front Neurol 2017, 8:258.

- Hegemann SCA, Wenzel A. Diagnosis and treatment of vestibular neuritis/neuronitis or peripheral vestibulopathy (PVP)? Open questions and possible answers. Otol Neurotol 2017;38:626-631.

- Herdman SJ. Vestibular rehabilitation. Curr Opin Neurol 2013;26:96-101.

- Katsarkas A, Outerbridge JS. Compensation of unilateral vestibular loss in vestibular neuronitis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1981;374:784-793.

- Magliulo G, Gagliardi S, Ciniglio Appiani M, Iannella G, Gagliardi M. Selective vestibular neurolabyrinthitis of the lateral and superior semicircular canal ampulla and ampullary nerves. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2012;121:640-644.

- Manzari L, MacDougall HG, Burgess AM, Curthoys IS. Selective otolith dysfunctions objectively verified. J Vestib Res 2014;24:365-373.

- Navari E, Casani AP. Lesion Patterns and Possible Implications for Recovery in Acute Unilateral Vestibulopathy Otol Neurotol 2020;41:250-255.

- Navari E, Cerchiai N, Casani AP. Assessment of vestibulo-ocular reflex gain and catch- up saccades during vestibular rehabilitation. Otol Neurotol 2018;39:1111-1117.

- Patel M, Arshad Q, Roberts RE, Ahmad H, Bronstein AM. Chronic symptoms after vestibular neuritis and the high-velocity vestibulo-ocular reflex. Otol Neurotol. 2016;37:179-184.

- Strupp M, Arbusow V, Maag KP, Gall C, Brandt T. Vestibular exercises improve central vestibulospinal compensation after vestibular neuritis. Neurology. 1998;51:838-844.

- Weber KP, Aw ST, Todd MJ, et al. Head impulse test in unilateral vestibular loss: vestibulo-ocular reflex and catch-up saccades. Neurology 2008;70:454–463 .

- Zellhuber S, Mahringer A, Rambold HA. Relation of video-head impulse test and caloric irrigation: a study on the recovery in unilateral vestibular neuritis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271: 2375-2383.

Resources for More Information

To learn more about SYNAPSYS VHIT — our innovative goggle-free solution for vestibular assessment — visit our dedicated page: https://www.inventis.it/en-na/products/video-head-impulse-test-synapsys-vhit