Editor’s Note: This text course is an edited transcript of a live webinar. Download supplemental course materials.

Learning Objectives

- Participants will be able to discuss the rising costs of dizziness presentations to US emergency rooms based on the articles presented.

- Participants will be able to explain the relevance to audiology clinical practice, of the articles presented.

- Participants will be able to discuss the results of a study on the HINTS and ABCD2 to screen for stroke in acute continuous vertigo and dizziness, and the implications for audiology clinical practice.

Introduction

Dr. Gary Jacobson: Today, we will cover a series of papers about dizziness and vertigo in the emergency room. I will be presenting the epidemiological background, and then Dr. McCaslin will discuss a proposal that others have made regarding management of dizziness and vertigo in the emergency room.

Article 1: Dizziness Preparation in U.S. Emergency Departments, 1995-2004 (Kerber, Meurer, West, & Fendrick, 2008)

This 10-year retrospective study was part of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. The study was a cross-sectional, annual survey. The studies were visits to randomly selected, non-institutional, general and short-stay hospitals in the United States with emergency or outpatient departments. The purpose of the study was to describe the characteristics in healthcare utilization information with the focus on dizziness. They were to take the data, analyze it, and comment on any trends that emerged. Then the trend information would be used to plan future research.

Methods

The data was collected from patient medical records during randomly assigned, four-week data collection periods from the sampled hospitals. There recorded a number of data points:

- Reason for the visit to the emergency room, with a maximum of three different reasons

- Key demographic information, including age and gender

- Condition of the patient at the time of presentation to the emergency room

- Discharge diagnoses, up to three

- Documented screening or diagnostic tests performed

- Calculated length of stay

- Prescribed medications

They did three types of analyses. The main one was a descriptive analysis. They also did a trend analysis to see what might be emerging, as well as logistic regression modeling. We will be talking mostly about the descriptive analysis.

Results

Out of 285,000 emergency room visits, about 7,000 were for dizziness and vertigo. That is about 2.5% or 25 visits per 1,000. In using this data, they estimated that over a 10-year period, this would amount to approximately 2.6 million dizzy and/or vertiginous patients per year over that period. That represented a 15% increase over the 1995 to 2004 period for people ages 45 to 64 years of age, and a 67% increase in people ages 65 and older.

Where dizziness was the primary reason for the visit, 36% of those patients had no additional reasons or symptoms for their visit. What is particularly interesting is that the rare diagnoses included stroke in the posterior circulation, which was about 4%, and there were no brain tumors and no central forms of vertigo in those patients. Figure 1 shows some accompanying reasons for referral in the sample of patients.

Figure 1. Accompanying reasons for referral.

A median of 3.6 tests were administered to the patients, and 14% of the subjects had 10 or more tests. Despite the small number of patients with central nervous system (CNS) diagnoses (4%), there was 169% increase of imaging studies from 1995 to 2004. Imaging included both CT and MRI scans, usually of the head. The rates of use were greatest for people 65 years of age or older. However, they reported that the largest increase over that period of time was a 281% increase for people 20 to 44 years of age.

The average time spent in the emergency room was about three hours, and about 20% of the visits resulted in a hospital admission. Those admissions tended to be older people.

Discussion

The authors commented that vertigo and dizziness presentations were increasing, but they were not quite clear as to why. Some of it may be the recommendation of the American Stroke Association, which is for people to call 911 immediately for dizziness or vertigo. It might also have to do with the lack of education of non-emergency department physicians who tell patients to go to the emergency room if acutely dizzy or vertiginous.

CT and MRI referrals increased dramatically over that 10-year period. It is not clear exactly what benefits were derived from imaging, particularly since CT scanning does not show cerebrovascular lesions in the acute period.

The rate of CNS diagnoses did not increase with the rate of imaging referrals. Stroke in the posterior circulation occurred about 3.2% to 3.9% of the time. The authors acknowledge that there is not a valid method to date to confirm if stroke is the cause of dizziness in the hospital.

The sensitivity of imaging to acute stroke is very low, and the number of referrals for imaging likely increased the length of stay. Guidelines for assessing stroke risk could contribute to the overall number of appropriate imaging referrals and positively affect patient care.

What do we know now that we did not know before from this paper? We know that dizzy patients seen in the emergency room account for about 2.5% (25 per 1,000) of all visits. We know that overall numbers of patients seen in the emergency room for dizziness and vertigo increased in that 10-year interval by 37%.

It is not surprising that there was greater increase for patients 65 years of age and older. Despite the fact that CNS origins of dizziness and vertigo were rare, about 4% of the time, referral for imaging increased 169% over the 10-year period, at great expense, by the way. We also know from this study that we are over-imaging people for non-neurological disorders. It would be helpful to have a way to determine when imaging is diagnostically warranted.

Article 2: Rising Annual Costs of Dizziness Presentations to U.S. Emergency Departments (Tehrani, Coughlan, Hsieh, Mantokoudis, Korley, Kerber, et al., 2013)

The second study by Tehrani and colleagues (2013) looks at the costs associated with imaging. This study begins with some epidemiological data. Approximately two million visits are made to the emergency department each year for dizziness or vertigo, which constitutes about 4.4% of symptoms for awake patients in the emergency room. Patients have longer lengths of stay and undergo more tests than patients without dizziness and vertigo. Neuroimaging, specifically CT and MRI, are overused despite their low sensitivity. The primary purpose of the investigation was to obtain an estimate of the national annual cost of managing patients with dizziness and vertigo in the emergency room and also to determine what fraction of annual total emergency cost this represents.

Examination of Historical Data

This study is a 15-year sample of dizziness and vertigo visits that numbered about 12,000; non-dizziness/vertigo visits numbered about 360,000. They identified a trend that visits for dizziness and vertigo steadily increased over that 15-year period from 2 million visits in 1995 to 3.8 million visits in 2009. The percent of visits from 1995 to 2009 of patients with dizziness and vertigo was relatively consistent, hovering around 3.4% to 3.5% of the total ER visits.

Additionally, there did not seem to be an effect of age for patients over 65 on visits to the emergency room for dizziness or vertigo. That figure hovers around 30% over that period of time without much change.

What did change was the percent increase in imaging use in the emergency room for dizziness and vertigo. It went from about 9% of the time in 1995 to 37% of the time in 2009. In fact, if you were dizzy and vertiginous, an MRI was performed about 96% of the time according to the investigators.

Results

The projected total number of dizziness/vertigo patients that presented to the emergency room was about 3.9 million. From 1995 to 2011, dizziness visits increased from 2 million to 3.9 million, equating to a 97% increase. It is interesting that non-dizziness visits increases only 44% of the time. From these data, we know that dizziness visits are increasing out of proportion compared to other emergency room visits.

The average cost per dizziness visit in the emergency department was about $1,000, which, over the group, gives an estimate of $3.9 billion in 2011. The costs were lower for people over the age of 65, which was unexpected. However, when they looked deeper, they found that a large number of these patients were being admitted, so any associated costs were billed as inpatient costs and not emergency room costs.

Three hundred and sixty million dollars was spent on non-contrast CT scans of the head, and another $110 million was spent on non-contrast MRI scans of the head. Roughly $470 million dollars of the $3.9 billion was spent on imaging.

Otologic and vestibular causes were the most common diagnoses seen in the emergency room. The cost estimate of $3.9 billion is 70% higher than a national estimate made in 1992, which was $2.32 billion. That increase reflects a rise in emergency room visits that were imaged. In 1992, out of 2 million patients, 10% were imaged. In 2011, out of 3.9 million patients, 40% were imaged. Yet, yield from imaging is very low. Remember that about 3.9% of the patients that we are seeing over multiple studies had central problems with posterior circulation stroke.

We know that about $4 billion is spent on patients who present to the emergency department with complaints of dizziness and vertigo and that diagnostic testing is responsible for a large part of the cost, about $470 million for both CT and MRI scans. Those costs could be reduced and tests could be limited to patients with neurological symptoms. The authors purported that more attention should be paid to streamlining diagnostic evaluations of dizziness and vertigo and that other cost-effective diagnostic patterns should be established that will not compromise care.

Discussion

What do we know now after reading this paper that we did not know before? From 1995 to 2009 there was almost a doubling of dizziness and vertiginous patients in the emergency room. That is from two million to about 3.8 million visits. The proportion who are equal to or over 65 years of age has been relatively stable. For the same period, CT referrals for dizzy patients increased from 9.4% to 37.4%, which is almost a four-fold increase. The cost of assessing dizzy patients is about $3.9 billion, with $470 million of that spent on imaging of the head; again, either CT or MRI. Costs could be reduced if tests were reserved for patients with neurological symptoms, since vertigo is almost always a peripheral origin.

The Proposal - Article 3: HINTS Outperforms ABCD2 to Screen for Stroke in Acute Continuous Vertigo and Dizziness (Newman-Toker, Kerber, Hsieh, Pula, Omron, Tehrani, et al., 2013)

Dr. Devin McCaslin: With the framework of research, I will discuss a proposal in regard to the statistics and financial consequences of all of these dizzy patients showing up at the emergency room.

The paper I will review today is on the HINTS test, which I will describe as well as the physiology behind it. The lead author on this paper is Dr. Newman-Toker. Over the last five years, he and his associates have been trying to develop ways that we can more efficiently and accurately diagnose patients that present to the emergency room, as well as discern whether or not it is a central or peripheral impairment.

Background

Dr. Jacobson covered much of the background, and I wanted to add a few more points. Primary dizziness and vertigo account for about four million emergency department visits annually. Those of us who are audiologists have all seen these patients. If fact, one of the questions we might ask on our intake form is, “Was your dizziness so severe that you went to the emergency room?” That is a signal for us during a case history that something happened, either peripherally or centrally.

Only 4% to 6% of these patients have episodes that are due to cerebrovascular causes. This is a small percentage of the patients presenting to the emergency room who need some sort of treatment for stroke or to be triaged in that way. That is where the issue lies. Stroke diagnosis in emergency department patients with vertigo is challenging because the majority have no obvious focal neurological signs at the initial presentation. What makes it so difficult for us to determine if the person has a peripheral issue like neuritis or something more serious?

Vestibular strokes may be misdiagnosed as a benign peripheral vestibular disorder. What often can be confused as a peripheral system may be a stroke in the posterior fossa, or posterior circulation stroke. These are strokes that occur either in the inferior cerebellum or the lateral brain stem. These brain regions are primarily involved in modulating balance-related sensory input from the eyes, somatosensory centers, and the inner ear. They are all gated through the cerebellum. The eye movements are also controlled there as well.

The problem is that there is no major motor or sensory tract in these brain regions. These patients do not present with anything other than dizziness. They do not show up with any stroke-like deficits such as hemiparesis, hemi-sensory loss, et cetera. They present with dizziness and vertigo. If the patient shows up at the emergency room and that physician says they have the same symptoms as a peripheral issue, how do they determine if it is a stroke or if it is a case where a medication can be given, the patient goes home, and compensation mechanisms will take care of it? That is a difficult issue.

In referral cases from Moulin and colleagues (2003), more than half of emergency department ear diagnoses are revised. This means they changed in the medical record what the patient’s diagnosis was. There is a high degree of inaccuracy for these patients that are showing up at the emergency room with this type of dizziness. What has been proposed and cultivated over the last five years primarily by the Johns Hopkins group and to some degree the University of Michigan group is to use a video oculography guided (VOG) decision rule as a way to discriminate between central and peripheral causes of vertigo. This eye movement exam is being used to determine where these patients should go and how they should be gated. Should they see neurology and be treated for a stroke, or should they go to otolaryngology?

For example, the patient presents to the emergency room with dizziness, nausea, vomiting, unsteady gait, and headache. From this point, we do not know if this person had a posterior fossa stroke or a peripheral vestibular system impairment. They both present with the same sort of symptoms. Instead of trying to figure it out, the physician orders an MRI,with which there are problems, to determine whether or not there was a stroke and then calls neurology. If it is an end-organ impairment or a peripheral problem, they will likely send you to otolaryngology for more extensive balance testing.

In the peripheral vestibular system, the membranous labyrinth is what we call peripheral. When we are trying to determine what the peripheral problem is, we are looking at the end-organ or nerves. There is a superior nerve and inferior vestibular nerve. If something attacks these or they become damaged, this will result in vertigo. If one of the end-organs loses its tonic activity, which drives the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR), then nystagmus occurs from the VOR, and patients complain of dizziness. Many times, they do not know if they are having a stroke or heart attack, and that will bring them to the emergency room. Although they are having a peripheral problem, they do not know what it is, and they will end up having an MRI.

Posterior Circulation Strokes

A more complicated issue is a posterior circulation stroke that can look similar to what happens if you lose the end-organ, either by neuritis or labrynthitis. When vestibular symptoms are of cerebrovascular cause, 90% are ischemic strokes in the vertebral basilar or the posterior circulation area (Tarnutzer, Berkowitz, Robinson, Hsieh, & Newman-Toker, 2011). The key question that we are trying to determine is how can the emergency physician determine if the impairment is peripheral or central? Right now, we primarily use the MRI, which is an enormous cost, considering that most of these are peripheral issues that do not need an MRI. An MRI will not add anything to the diagnosis.

The posterior fossa includes the cerebellum and the brain stem. A stroke in this area will give us similar issues to those that we see in a peripheral problem. This is because of the blood supply in the superior cerebellar artery, the anterior inferior cerebellar artery, the posterior inferior cerebellar artery, and the vertebral artery. If you have a thrombosis or ischemic event in any of these blood vessels, the eye movement system will be affected as well. There are no sensory or motor tracts that run through here, so there are no symptoms like weakness in their arm or facial paralysis. Their complaint is dizziness.

How can we determine if the problem is central or peripheral? Currently, the MRI is the gold standard, also called MRI diffusion weighted imaging (DWI). It has been shown that there can be false negatives, especially early on. This is key. I will show more data showing that using MRI may not be the best way to identify patients with peripheral or central issues. One report shows a substantial false negative rate of 20%, meaning the MRI did not show anything in the first 24 hours. If you have a patient with a posterior fossa stroke who is having terrible dizziness and they present to the emergency room, there is a 20% false negative rate, meaning the MRI will miss it. That is enormous. As time goes by, it becomes more sensitive, but it can be dangerous to rely solely on an MRI to sort these patients out.

In this study (Newman-Toker, et al., 2013), the authors compared the accuracy of two bedside tests as a possible screening method in patients with dizziness who are presenting to the emergency room. You will not use this in your clinic six months after the fact. One is the HINTS test, and the other is the ABCD2, which is a clinical decision rule to assess short-term risk of strokes in patients.

This article pits these two tests against each other. This is odd, because the two tests look at two different things. The purpose of the HINTS is to separate peripheral from central impairments for patients with continuous dizziness. The ABCD2 is not concerned with any peripheral problems. It looks at whether or not you had a stroke. You need to keep that in mind when comparing these two tests.

HINTS

The HINTS exam, Head Impulse Nystagmus Type Test of Skew, is a three-step clinical decision rule. It is composed of three eye movement exams, and it is for patients with acute continuous dizziness. Again, this is key. You do not want to put people into this testing system if they have transient vertigo, like benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). This is for people in the emergency room. There is also a HINTS Plus in which they has an audiogram added to it.

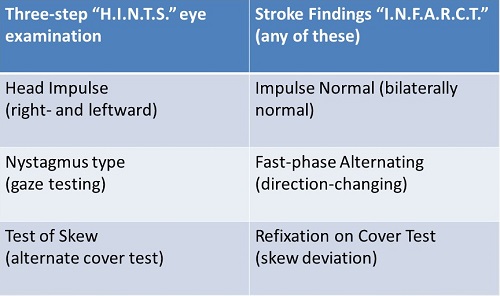

That is to be contrasted with stroke findings. Figure 2 shows a chart with the three HINTS tests on the left side and what the findings would be in a stroke on the right side. Each test or finding has an acronym: HINTS – INFARCT. You are looking for differences in the chart in order to determine whether that person had a posterior fossa stroke or a peripheral event.

Figure 2. HINTS - INFARCT comparison.

The Head Impulse is the same as was described by Halmagyi and Curthoys in 1988. The idea is you have the VOR at high frequencies. The VOR will move the eyes 180 degrees out of phase, and it will keep the fovea on the target that the patient is interested in viewing. The vestibular system drives that. It is out of the frequency range of the ocular motor system.

If one of the end organs is impaired due to a peripheral problem, the VOR will not drive the eye 180 degrees out of phase. When you thrust the head towards the side of the impairment, the eyes are going to travel to some degree with the head, and that will remove the fovea from the target. When the head stops, the patient will no longer be looking at the target, and they will have move their eyes back to reacquire the target. That little jump back is called a catch-up saccade. That is a positive head impulse test. Essentially, you are moving the head so quickly that you are outside the range of anything else other than the VOR that can keep the fovea on the target.

A new piece of video equipment on the market incorporates the HINTS test. This is essentially the same head impulse test that we have been doing since 1988 by the bedside. However, we now have a set of goggles that can track the eye and give us quantitative data with regard to the gain and velocity of the head and the eye movement, and will allow us to see clearly these catch-up saccades that occur when the eye comes off the target.

Physiology

The first thing is the head impulse test, then the acute spontaneous nystagmus. You need a peripheral pattern on the HINTS test of peripheral nystagmus. This is present without provocation, meaning that the patient has spontaneous nystagmus. If the cerebellum is intact and there is a peripheral end-organ impairment, the nystagmus will diminish or get smaller in amplitude when you ask the patient to fixate. It follows Alexander’s Law, in that it always beats the same direction in a peripheral problem. When you look towards the side where the nystagmus is beating, it gets larger, less in the center, and the furthest away, which follows Alexander’s Law.

In skew deviation, you are doing an alternate cover test. You ask the patient to cover up each eye with the tool, and you assess the patient’s ability to keep their eye fixated on the target when you cover up the other eye. If you have an impairment, the eye will move. One eye will be up and one will be down. You occlude each eye separately.

When you cover the second eye, the other eye will move to refixate on the target. When you cover the eye up, the uncovered eye will move up and then when you move the cover away, the eye will have to come back down. You are looking for this refixation. That is a strong central sign that the eyes are misaligned vertically. Normal people do not do this.

They have added a fourth test to the HINTS Plus, and this is the hearing test. They want to see how hearing loss, using a portable audiometer in the emergency room, increases the sensitivity of the HINTS test.

When ruling out a peripheral impairment, you are looking for patterns of findings on the HINTS test. For a peripheral impairment, Newman-Toker (2013) would argue that you should see an abnormal head impulse test, meaning when you moved your head very quickly, the eye comes off the target, meaning there is an abnormality in the VOR causing a reduction in VOR gain, and the eye has to refixate. This is a positive head impulse test. You are looking for direction-fixed spontaneous nystagmus that follows Alexander’s Law. It always beats the same direction.

You are also looking for no evidence of skew deviation. When you cover up each eye, you should not see any refixations as you move from one eye to the other. That would be considered a peripheral impairment.

ABCD2

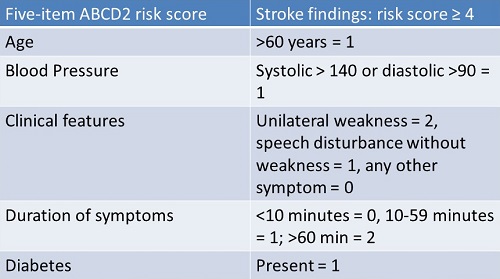

The HINTS is compared to the ABCD2. This is a risk prediction score. They ask the patient a number of questions, and it gives you a score based on how likely it is the patient had a stroke. The ABCD2 score correlated to the risk of cerebrovascular diagnosis (Navi, Kamel, Grossman, Wong, Poisson, Whetstone, et al., 2012). The questions asked are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Five stroke risk categories and the findings with score points.

They ask about age, unilateral weakness in the hand, arm, or leg, speech disturbances, blood pressure, duration of symptoms and the presence of diabetes. The score can tally from zero up to seven. This study compared the HINTS test with the ABCD2 test to determine which one best separates peripheral from central pathology.

Central Impairment

If it is a central pattern, Newman-Toker et al. (2013) argues that you have a bilateral, normal head impulse test. There would be no re-fixation saccades and gain would be normal. Furthermore, you may have bilateral, direction changing, horizontal gaze-evoked nystagmus, or predominantly vertical or torsional nystagmus. You would see skew deviation by alternate cover test. Any combination of these would indicate that the patient has had a posterior fossa stroke.

The idea is that the patient comes into the emergency room, they give them the HINTS test, and if the patient shows this pattern, then it is central, and they go to the neurologist. If they have the other pattern we discussed earlier, they would go to otolaryngology.

Outcomes

The authors (Newman-Toker, et al., 2013) included 190 patients. They looked at acute vestibular syndrome, which is what we are calling a peripheral problem, and the symptoms were acute vestibular syndrome, acute persistent vertigo or dizziness with nystagmus, nausea or vomiting, head motion intolerance, and new gait unsteadiness. They all underwent a neurotology examination and neuroimaging. Almost every patient received an MRI or a CT scan. Everyone received the HINTS test, and everyone received the ABCD2 test. They were asked the questions, indicating that a positive stroke had to score greater than 4 on those questions.

Sensitivity. They looked at the sensitivity, which is the ability of a test to identify if a person has a problem, and the specificity of these tests. They were also interested in the false negative neuroimaging. The final diagnoses made in the two studies were 35% vestibular neuritis, 60% posterior fossa strokes, and the rest were other central causes.

When comparing the sensitivity of the two tests for stroke, the numbers were very powerful in terms of being able to accurately decide whether or not a person has a stroke or has a peripheral vestibular system impairment.

The authors did not want age to be a factor, but they did evaluate the results overall with all participants, and then separated into three categories of age: 18-49, 50-59, and 60-92. The evidence for all age groups is indicative that both tests have compelling sensitivity, with the HINTS Plus scoring higher than the ABCD2.

MRI performance. MRI performance is a key factor. Initial MRIs were falsely negative in 15 of 105 of the patients, equating to a 14.3% false negative rate, which means that the MRI showed normal imaging in the presence of a disorder. So you have identified a patient with dizziness. You do an MRI and it is normal. You send them home, and they end up getting swelling, or obstructive hydrocephalus. It can become much worse if you miss that. The MRI sensitivity is about 85.7 in these strokes. If you have a patient with a stroke and you send them home, you can also have brainstem compression.

Summary of Findings

The HINTS decision rule outperformed the ABCD2 for detecting stroke or other central causes in acute vestibular syndrome (peripheral issues). The HINTS approach was more sensitive for stroke than MRI-DWI in the first 48 hours. Their argument is that the eye movements are more sensitive than the MRI, which has been published numerous times.

HINTS may provide a way for differentiating peripheral impairments from stroke when clinicians have appropriate training. Newman-Toker (2013) makes the case that neurotologists or neuro-ophthalmologists that are trained in the eye movements can make the diagnosis; it is when you give these tools to emergency room physicians that the diagnostic process is chaotic. These physicians are not typically trained in whether it is bidirectional, gaze-evoked nystagmus, down-beating, or direction-fixed nystagmus. The sensitivity of the HINTS test, when administered by people with sophisticated training, is very high.

For patients that are suspected to have peripheral impairments with negative early MRI and a HINTS suggestive of stroke (if the HINTS came out positive for stroke, but you had a normal MRI), they would argue that you should redo the MRI in three to seven days. We know that the same vertiginous symptoms can suddenly appear again in approximately 15% of people, which is fairly large.

In a nutshell, people who were positive on the HINTS test would be people who get imaging in the emergency room.

Video Head Impulse Test

The video head impulse test (V-HIT) is a relatively new technology. One exciting development is that the V-HIT is abnormal in central strokes as well. Posterior fossa strokes may be able to create an abnormal V-HIT. If you have an abnormal V-HIT, that would put you in the peripheral bin. It may be a little more complicated than we thought. If you lose the anterior inferior cerebellar artery, the rest of the system loses blood flow, and it will manifest as a peripheral complication when, in fact, it is a stroke.

Conclusion

This diagnostic process may be more complicated then we think. The HINTS test shows high sensitivity in the hands of very skilled neurotologists or neuro-ophthalmologists. As we see, the V-HIT may also give us some indications about stroke, but the question will be, “How do you differentiate those two?” I imagine that is where some of this new research will go.

Questions and Answers

Is headache a common symptom of a vestibular disorder?

It is more in central issues, but you can have it in a patient that has lost an end-organ. Their blood pressure is up, they have anxiety and are stressed. Headache manifests itself in both populations.

Some authors classify skew deviation into different types to differentiate if it is peripheral or central.

That is very true. We will see skew deviation in people who have utricular disorders acutely, and you can also see it in people who have brainstem impairments. It is the same thing with the V-HIT; some of these tests can be abnormal both in peripheral and central disorders.

Can rapid side to side nystagmus occur without the symptoms of dizziness?

This kind of nystagmus, or congenital nystagmus, could occur without symptoms of dizziness.

What diagnosis remains from peripheral vestibular disorders after taking BPPV as a differential diagnosis from stroke? Is it only vestibular neuritis?

The physician would argue a labrynthitis or neuritis or any sort of end-organ impairment. BPPV is not considered in this. It would be considered transient. The key to this is subject selection; you have to take people that are presenting with continuous dizziness. This means the patient is sitting in the emergency room saying, “I am dizzy,” not, “I get dizzy when I lie down.”

References

Halmagyi, G. M., & Curthoys, I. S. (1988). A clinical sign of canal paresis. Archives of Neurology, 45(7), 737-739.

Kerber, K. A., Meurer, W. J., West, B. T., & Fendrick, A. M. (2008). Dizziness presentations in U.S. Emergency Departments, 1995-2004. Academic Emergency Medicine, 15(8), 744-750. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00189.x.

Moulin, T., Sablot, D., Vidry, E., Belahsen, F., Berger, E., & Lemounaud, P. (2003). Impact of emergency room neruologists on patient management and outcome. European Nuerology, 50(4), 207-214. doi: 10.1159/000073861.

Navi, B. B., Kamel, H., Shah, M. P., Grossman, A. W., Wong, C., Poisson, S. N., Whetstone, W. D., et al. (2012). Application of the ABDC2 score to identify cerebrovascular causes of dizziness in the emergency department. Stroke, 43(6), 1484-1489. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.11.646414.

Newman-Toker, D. E., Kerber, K. A., Hsieh, Y. H., Pula, J. H., Omron, R., Tehrani, A. S., et al. (2013). HINTS outperforms ABCD2 to screen for stroke in acute continuous vertigo and dizziness. Academic Emergency Medicine, 20(10), 986-996. doi: 10.1111/acem.12223.

Tehrani, A. S., Coughlan, D., Hsieh, Y-H., Mantokoudis, G., Korley, F. K., Kerber, K. A., et al. (2013). Rising annual costs of dizziness presentations to U.S. emergency departments. Academic Emergency Medicine, 20(7), 689-696. doi: 10.1111/acem.12168.

Cite this Content as:

McCaslin, D., & Jacobson, G. (2015, June). Vanderbilt Audiology Journal Club - vestibular update. AudiologyOnline, Article 14168. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com