Learning Outcomes

After reading this article, professionals will be able to:

- Describe criteria for hearing screening protocols that are most appropriate for preschool and young school-age children.

- Define two criteria for pass versus refer outcome for hearing screening with distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAEs).

- State the rationale for including a test frequency of 6000 Hz for pure tone hearing screening of children age 7 years and older.

Rationale for Hearing Screening of Preschool and School-Age Children

Hearing loss is the most common developmental disorder identifiable at birth, and the prevalence of hearing loss increases from birth through childhood due to the occurrence of delayed-onset, progressive, and acquired causes of hearing loss. An estimated 15% of teenagers in the United States have some degree of hearing loss in one or both ears. Childhood hearing loss of any degree may have a negative impact on speech and language abilities, pre-reading and reading skills, school performance, and psychosocial status. Preschool and early school-age children learn mostly through the auditory modality. Appropriate learning in a typical classroom setting requires consistently effective and efficient perception of speech. Hearing loss, including mild or fluctuating hearing loss, interferes with accurate perception of speech. The impact of hearing loss and auditory processing disorders on learning is even greater in not uncommonly noisy classroom environments. The multiple negative effects of hearing loss may mimic and may also enhance those for children with attention deficit disorders, learning disabilities, impaired language processing, and cognitive delays.

Substantial clinical research confirms the benefits of early identification of and appropriate intervention for hearing loss, that is, within the first six months of life. However, some children later acquire progressive or late-onset hearing loss hearing loss in the preschool years. With early and appropriate intervention, young children with hearing loss have the potential to develop normal speech and language and an opportunity to achieve typical school performance.

The purpose of hearing screening of preschool and school-age children is to identify and refer for appropriate medical or non-medical management children who are likely to have hearing loss that would interfere with communication and school performance. Specific objectives of annual hearing screening include:

- Identifying students with potential auditory dysfunction and associated hearing loss, even mild, unilateral, or fluctuating hearing loss.

- Preventing or mitigating hearing loss that may affect a child’s health or learning.

- Professional care for children at risk for hearing loss, regardless of financial limitations.

- Notifying and educating parents/guardians of hearing screening results with recommendations for further audiological and/or medical assessment.

- Notifying classroom teachers about students with hearing loss, and providing recommendations for appropriate classroom and educational accommodations

- Educating students and their parents/guardians about hearing protection, including the permanent damaging consequences of exposure to high levels of noise and music.

Limitations of Hearing Screening with the Pure Tone Technique

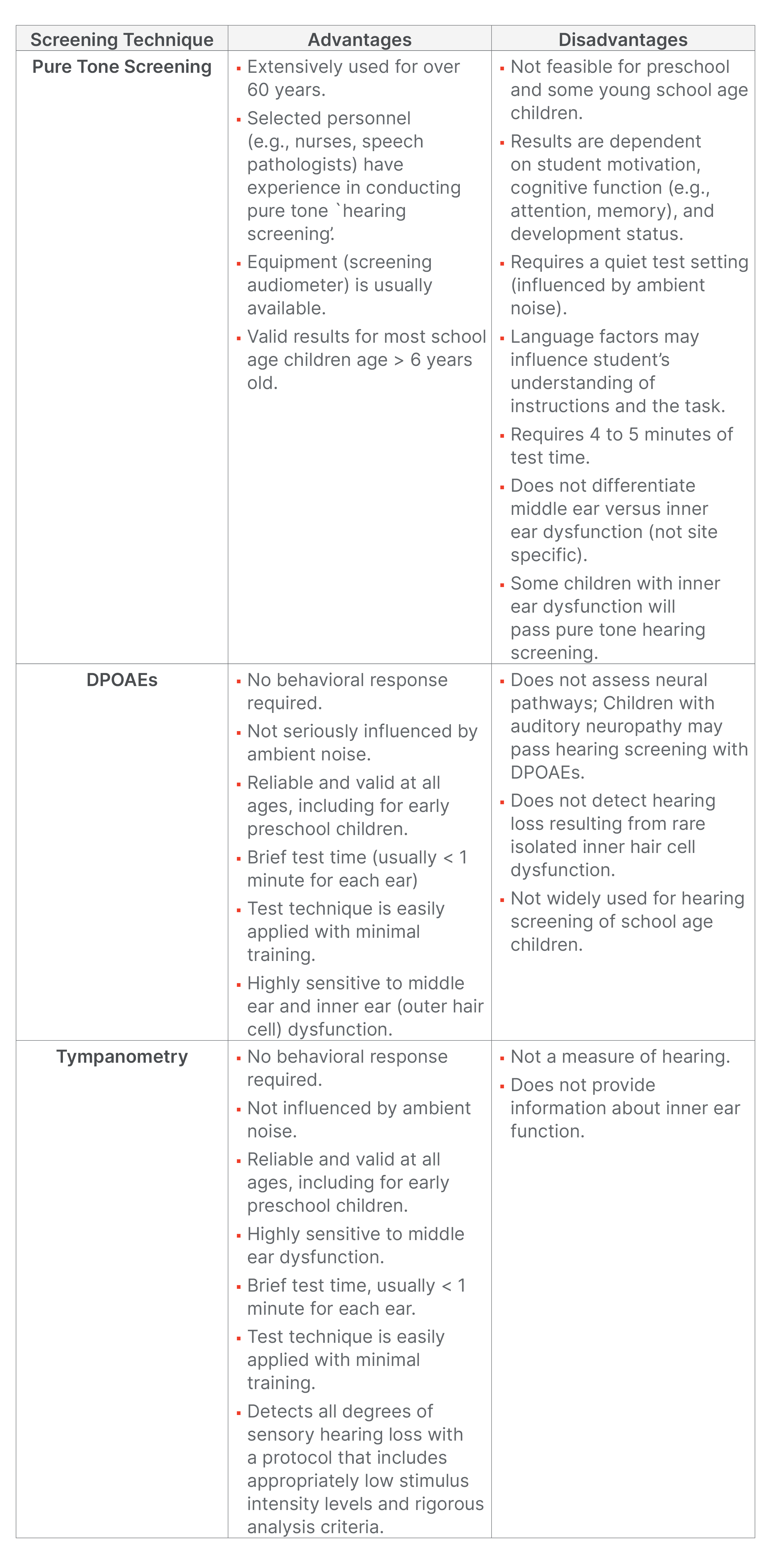

Traditionally, the pure tone technique has been preferred for hearing screening in children. Guidelines for the American Speech Language and Hearing Association (ASHA, 1997) and the American Academy of Audiology (AAA, 2011) describe in detail the hearing screening of children with the pure tone technique. However, over 70 years of experience with pure tone hearing screening has revealed serious methodological limitations and practical problems with test performance, particularly for hearing screening of preschool and young school-age children. The advantages and disadvantages of pure tone hearing screening are summarized in Table 1. There is general acknowledgment in hearing screening guidelines that hearing screening of young preschool children is difficult or not feasible with behavioral techniques, specifically the pure tone hearing screening technique (Kleindienst Robler et al., 2023; Krishnamurti et al., 1999; Allen et al., 2004; Serpanos & Jarmel, 2007).

A real-world study in pediatricians’ offices (Halloran et al., 2005) provided evidence suggesting that relying on the pure tone hearing screening technique is problematic even for older preschool children and young school-age children. The authors report a pass rate of only 67% for 21 developmentally delayed children (2% of the total population). The overall failure rate was 10%, but a total of 162 children, or 15% of the population, either failed hearing screening or could not be tested. One of the rather surprising findings was the reluctance of pediatricians to refer children for further evaluation. As Halloran et al. (2005) note: “The findings from this study are worrisome because physicians took no further action in more than 50% of the children who failed the hearing screening and more than 70% of the children who could not be tested” (p. 934).

Dr. Donna Halloran and two of those same authors published a follow-up article (Halloran et al., 2009), four years later that looked at the validity of pure tone screening at well child visits. The authors raise serious questions about the value of pure tone hearing screening during well-child visits because of poor sensitivity (50%) and only fair specificity (78%), plus a high no-show rate for children referred for complete hearing evaluation by their primary care physician. Based on their data, Halloran et al (2009) conclude: “Given the poor validity of pure tone audiometry, other methods of hearing screening should be considered for the primary care setting. One such option that practices and schools are increasingly using is otoacoustic emissions” (p. 161).

Collective experience from multiple peer-reviewed published studies highlights at least five serious challenges associated with reliance on the pure tone technique for hearing screening of preschool and young school children:

- Non-audiologist personnel do not have adequate experience using the special test techniques required to obtain valid pure-tone hearing screening findings in preschool children. Audiologists are rarely available at sites where preschool hearing screening is conducted, such as daycare centers, Head Start centers, or public elementary schools.

- Acceptable ambient sound levels are not always achievable in typical preschool hearing screening settings for pure-tone audiometers with supra-aural earphones.

- Screening time, including instructions and data collection, is usually 4 to 5 minutes or longer for each child.

- Pure tone hearing screening doesn’t consistently identify middle ear disorders which is a commonly encountered problem in the preschool population.

- A child’s developmental age, cognitive level, and language skills are significant factors in the accuracy or even the feasibility of pure tone hearing screening. Because of these factors, hearing screening cannot be successfully completed for most children under 6 years of age and at least 3 to 5% of older preschool populations (Halloran et al., 2005; Krishnamurti et al., 1999; Allen et al., 2004; Serpanos & Jarmel, 2007). Also, the inability to test children who are developmentally delayed is unacceptably high using pure tone screening, even when an audiologist performs the test.

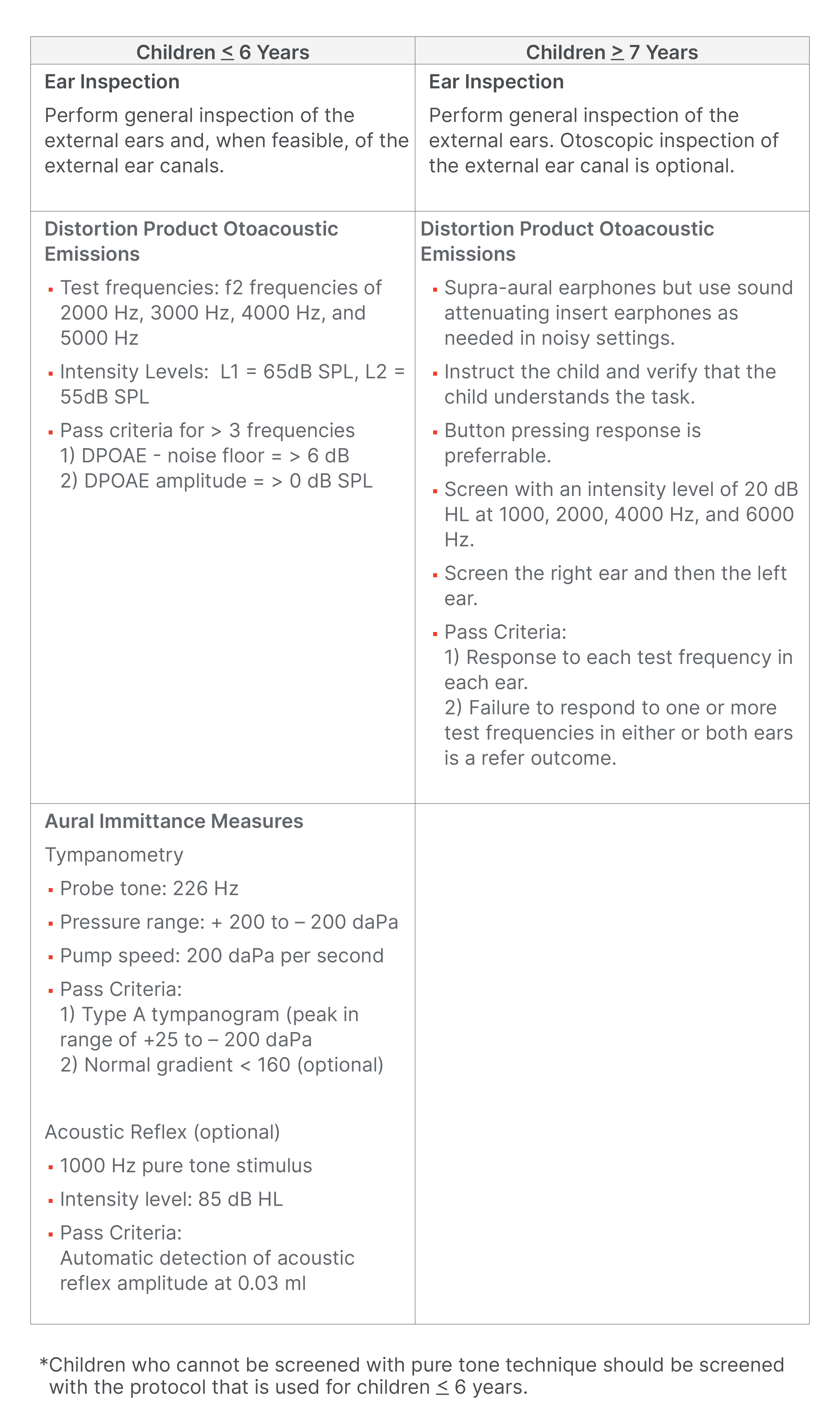

Due to the difficulty in using pure tone screening in young school-aged children, we recommend that otoacoustic emissions (OAE) be used as an alternative objective measure. Also due to the high rates of ear infections in younger children, it is recommended that a combination of tests be used that includes a hearing component and a measurement of middle ear health, tympanometry. For preschool and young school-aged children, we recommend OAE and tympanometry and for older children (7+ years of age), pure tone screening with tympanometry is recommended. Each of these objective techniques is now reviewed.

Objective Hearing Screening Techniques

Otoacoustic Emissions (OAEs)

OAEs are an attractive option for hearing screening in preschool and school-age children under seven years of age. Multiple advantages of OAEs, summarized in Table 1, support their role in preschool and early school-age hearing screening.

Table 1. Advantages and disadvantages of three hearing screening techniques. Click here for a larger version of Table 1.

As an objective technique, OAE findings are not influenced by the many listener variables that confound hearing screening with behavioral techniques, as already noted. Sensitivity to auditory problems commonly encountered in preschool children is a major advantage of OAEs. Abnormal OAE findings are very likely in children with middle ear dysfunction and/or with inner ear hearing loss involving outer hair cell dysfunction. Most etiologies for childhood hearing loss affect outer hair cell function.

Recording OAEs in young children is feasible and technically rather simple as evidenced by the widespread application of OAEs in newborn infants undergoing hearing screening (see Joint Committee on Infant Hearing, 2019; Dhar & Hall, 2018 for review), as well as preschool and young school-age children (Ho et al., 2002; Eiserman et al., 2008; Bhatia et al., 2013; Kreisman et al., 2013). An audiologist is not required for OAE-based hearing screening. OAE screening test time is quick, often less than 30 seconds per ear. The signal averaging process employed during OAE measurement, in combination with a properly fitted probe tip, permits screening in test environments with rather substantial levels of ambient noise. A quiet test setting is not a requirement for OAE screening. OAE devices are easily portable and often hand-held. Also, the OAE test outcome is documented with a display that can be stored electronically, interfaced with data management systems, and printed immediately. With appropriate low stimulus levels and rigorous criteria for automated analysis, OAE screening can detect children with mild hearing loss.

Aural Immittance Measures: Tympanometry and Acoustic Reflex

The term aural or acoustic immittance refers to objective procedures that measure the mobility and stiffness of the tympanic membrane and the middle ear (Hall, 2014; Hall, 2016). Tympanometry contributes importantly to hearing screening of preschool and young school-age children because middle ear dysfunction is not uncommon. Measurement of the acoustic reflex, which is feasible in infants and young children (Kei et al., 2002), simultaneously provides information on the function of multiple auditory regions, including the middle ear, the inner ear, the auditory (8th cranial) nerve, auditory structures in the brainstem, and the facial (7th cranial) nerve.

Modern clinical instruments for aural immittance measurement, including screening devices, offer an option for automatically initiating the test process as soon as an airtight seal is created between the probe and the walls of the external ear canal. This feature is especially handy for testing infants and young children as the tester can focus on securing an airtight seal between the probe and the external ear canal without also attempting to operate the immittance device. Detection of the acoustic reflex is an option in aural immittance measurements conducted with a screening tympanometry device. With a screening device, the acoustic reflex is typically recorded in only the ipsilateral condition, i.e., the stimulus is presented to one ear, and the change in compliance is recorded in the same ear. The advantages of aural immittance screening measures versus traditional pure-tone hearing screening are summarized in Table 1.

A New Research-Based Protocol for Childhood Hearing Screening

Recent research offers compelling support for a combined OAE + tympanometry hearing screening approach for preschool and young school-age children (e.g., Ho et al., 2002; Dhar & Hall, 2018; Robler et al., 2023; Emmett et al., 2019). Table 2 shows two protocols for hearing screening of preschool and young school-age children (Protocol 1) and school-age children aged 7 years and older (Protocol 2). Robler et al. (2023) recently reported a formal study of over 1400 children living in rural Alaska who ranged in age from preschool to the 12th grade.

Table 2. Protocols for hearing screening of preschool and young school-age children (< 6 years) versus school-age children aged 7 years and older. Click here for a larger version of Table 2.

Their study provides compelling evidence in support of hearing screening using a combined DPOAE + tympanometry approach for children younger than 7 years. Robler and colleagues (2023) state that a combination of DPOAEs and tympanometry is the preferred approach for hearing screening of children aged 6 years and younger, as it was the most accurate at identifying children in need of follow-up, particularly for those living in rural environments. A substantial proportion of children in this age range cannot reliably complete pure tone hearing screening. DPOAEs are a sensitive technique for detecting permanent sensory hearing loss. The addition of tympanometry enhances the detection of middle ear dysfunction, even in children without hearing loss.

Notice in Table 2 that the pure tone technique used with children aged 7 years and older includes a test frequency at 6000 Hz, in addition to the typical test frequencies of 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz. As Robler et al. (2023) point out, the addition of the 6000 Hz test frequency increases the likelihood of identifying hearing loss secondary to noise or music exposure in older school-age children, including adolescents and teenagers. Increased prevalence of sound-induced hearing loss in this population is now a well-recognized public health concern (e.g., Dillard et al., 2022; Serra et al., 2014; Shargorodsky et al., 2010). Quick and accurate pure-tone hearing screening is feasible for most children aged 7 years and older. However, the combined DPOAE + tympanometry screening approach should be immediately implemented for any older school-age children who, for any reason, cannot successfully complete pure tone hearing screening in a timely fashion.

Referral Criteria

Criteria for a pass outcome with each of the hearing screening approaches are noted in Table 2. To pass DPOAE screening a child must have for at least three of four test frequencies with DP amplitudes that are > 6 dB above the noise floor and DP absolute amplitudes of > 0 dB SPL. Referral criteria for the tympanometry screening approach include a type B (flat) tympanogram or type C tympanogram with a negative pressure peak at < - 200 daPa or a gradient value of < 160. Children who fail either DPOAE or tympanometry screening in either ear warrant referral to an audiologist and/or physician. The typical referral criterion for pure tone hearing screening is simply the absence of a response to the 20 dB HL presentation of one or more test frequencies in either or both ears.

Conclusions

Research supports a new approach for hearing screening of preschool and young school-age children with a combination of two objective measures of auditory function, DPOAEs + tympanometry. The combined DPOAE + tympanometry screening approach is effective in the detection of sensory hearing loss and middle ear dysfunction. Importantly, reliable objective hearing screening is feasible for all preschool and young school-age children. The pure tone hearing screening technique is best reserved for children aged 7 years and older. The addition of a pure tone test frequency of 6000 Hz enhances the likelihood of detection of sound (music or noise) induced hearing loss. Supplementing pure tone hearing screening with tympanometry ensures the detection of middle ear dysfunction, even in children without hearing loss.

References

Allen, R. L., Stuart, A., Everett, D., & Elangovan, S. (2004). Head Start hearing screening: Pass/refer rates for children enrolled in a Head Start Program in Eastern North Carolina. American Journal of Audiology, 13, 29-38.

American Academy of Audiology (2011). Childhood Hearing Screening Clinical Practice Guidelines. www.audiology.org

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (1997). Guidelines for Audiological Screening. www.asha.org

Bhatia, P., Mintz, S., Hecht, B.F., Deavenport, A.A., & Kuo, A.A. (2013). Early identification of young children with hearing loss in federally qualified health centers. Journal of Development and Behavioral Pediatrics, 34, 15–21.

Dhar, S., & Hall, J.W. III (2018). Otoacoustic emissions: Principles, procedures & protocols. Plural Publishing.

Dillard, L. K., Arunda, M. O., Lopez-Perez, L., et al. (2022). Prevalence and global estimates of unsafe listening practices in adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Global Health, 7, e010501. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2022-010501

Eiserman, W., Hartel, D., Shisler, L., Buhrmann, J., White, K., & Foust, T. (2008). Using otoacoustic emissions to screen for hearing loss in early childhood care settings. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 72, 475-482.

Emmett, S. D., Kleindienst Robler, S., Gallo, J. J., Wang, N.-Y., Labrique, A., & Hofstetter, P. (2019). Hearing Norton Sound: Mixed methods protocol of a community randomized trial to address childhood hearing loss in rural Alaska. BMJ Open, 9(1), e023081. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023081

Hall, J. W. III. (2014). Introduction to audiology today. Pearson Educational.

Hall, J. W. III. (2016). Effective and efficient preschool hearing screening: Essential for successful early hearing detection and intervention (EHDI). Journal of Early Hearing Detection and Intervention, 1, 1-12.

Halloran, D., Hardin, M., & Wall, T. C. (2009). Validity of pure-tone hearing screening at well-child visits. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 163, 158-163.

Halloran, D., Wall, T., Evans, H., Hardin, J., & Woolley, A. (2005). Hearing screening at well-child visits. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 159, 949-955.

Ho, V., Daly, K., Hunter, L., & Davey, C. (2002). Otoacoustic emissions and tympanometry screening among 0-5 year olds. Laryngoscope, 112, 513-519.

Joint Committee on Infant Hearing (2019). Year 2019 Position Statement: Principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. Journal of Early Hearing Detection and Intervention, 4(2), 1-44.

Kei, J., Robertson, K., Driscoll, C., Smyth, V., McPherson, B., Latham, S., & Loscher, J. (2002). Seasonal effects on transient evoked otoacoustic emission screening outcomes in infants versus 6-year-old children. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 13, 392-399.

Kleindienst Robler, S., Platt, A., Jenson, C. D., Meade Inglis, S., Hofstetter, P., Ross, A. A., Wang, N.-Y., Labrique, A., Gallo, J. J., Egger, J. R., & Emmett, S. D. (2023). Changing the paradigm for school hearing screening globally: Evaluation of screening protocols from two randomized trials in rural Alaska. Ear & Hearing, 44(4), 877-893. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0000000000001336

Kreisman, B. M., Bevilacqua, E., Day, K., Kreisman, N. V., & Hall, J. W. III. (2013). Preschool hearing screenings: A comparison of distortion product otoacoustic emission and pure tone protocols. Journal of Educational Audiology, 19, 49-57.

Krishnamurti, S., Hawks, J. W., & Gerling, I. J. (1999). Performance of preschool children on two hearing screening protocols. Contemporary Issues in Communication Sciences and Disorders, 26, 63-68.

Serpanos, Y. C., & Jarmel, F. (2007). Quantitative and qualitative follow-up outcomes from a preschool audiologic screening program: Perspectives over a decade. American Journal of Audiology, 16, 4-12.

Shargorodsky, J., Curhan, S. G., Curhan, G. C., & Eavey, R. (2010). Change in prevalence of hearing loss in US adolescents. Journal of the American Medical Association, 304(7), 772-778.

Citation

Hall, J.W.III., & Kleindienst Robler, S. (2024). A new strategy for hearing screening of preschool and school-age children. AudiologyOnline, Article 29069. Available at www.audiologyonline.com