From the Desk of Gus Mueller

From the Desk of Gus Mueller

OTC hearing aids. The mantra always has been affordability and accessibility. Sounds good, but how is that idea really impacting hearing aid adoption? A little history: Some of you might remember back in 2003, when Mead Killion filed a petition that called for a hearing aid that could be sold over-the-counter as an affordable alternative to custom hearing aids. Citing a concern for public health (e.g., medical clearance for hearing aids) the FDA turned down the petition in 2004.

The topic was picked up in 2009 at an NIH conference and later by NASEM. In 2016, this latter group issued a set of 12 recommendations. Shortly after, the OTC hearing aid act was introduced, and it was passed and signed into law in 2017. It was not until October 2021, however, that the FDA released the draft regulations. The 200-page document was finally filed in August, 2022, and went into effect on October 17, 2022—just a little over 3 years ago.

Today, there are well over 100 FDA-registered/cleared OTC products. But it gets more complicated. We still have PSAPs. We also have a category known as direct-to-consumer (DTC), which is really a delivery channel and can consist of anything from a PSAP to an OTC to a prescription product. And we can’t forget about “hearables.”

More important than the confusing labeling, however, is answering the frequently-asked question: “How good are today’s OTC products?” In the past couple years, there have been dozens of published research studies related to OTC hearing aid products. A couple of these articles have reported that OTCs perform better than “prescription” hearing aids, while on the other hand, at least one study found that using these instruments is no better than unaided (Brian Taylor and I recently reviewed 20 or more of these OTC articles in an October 2025 Research Quick Takes article). I think it’s time to bring in someone to give us clarity—someone who actually has been involved in some of these studies.

Vinaya Manchaiah, AuD, MBA, PhD, is Professor of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and Director of Audiology at the University of Colorado Hospital (UCHealth). He also serves as Principal Investigator at the Virtual Hearing Lab. He holds additional academic appointments as Extraordinary Professor at the University of Pretoria (South Africa) and Adjunct Professor at the Manipal Academy of Higher Education (India).

Most of you are familiar with Dr. Manchaiah’s work. At last count, the number of his peer-reviewed articles is approaching Jerger-esque territory. He also is the author or editor of six books related to audiology, hearing science, and patient-centered care. He has received numerous accolades, including awards from the American Academy of Audiology and the British Society of Audiology.

As stated in his bio, Vinay’s research focuses on improving access to and outcomes in hearing and balance care by leveraging digital health solutions, enhancing self-management, and addressing global disparities in service delivery. Hmm—this all seems to relate to OTC hearing aids. It’s not surprising, therefore, that you’ll find all this and more in his excellent 20Q article.

Gus Mueller, PhD

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller CEU articles at www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

Note: The information in this article was accurate at the time of writing. Proposed changes to the federal budget may impact the ongoing funding of newborn hearing screening and intervention services.

20Q: Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids and Service Delivery Models—What We Know, and What Remains Unclear

Learning Outcomes

After reading this article, professionals will be able to:

- Describe the key characteristics and differences between over-the-counter (OTC) and professionally dispensed hearing devices.

- Summarize the current evidence base regarding the accessibility, feasibility, efficacy, and limitations of OTC hearing aids and direct-to-consumer (DTC) hearing care models.

- Identify gaps in knowledge and areas for future research related to OTC hearing aid outcomes, consumer behavior, and service delivery models.

1. I certainly have heard a lot about OTC hearing aids in recent years, but then I sometimes also hear the term “direct-to-consumer?” Same thing?

Sometimes yes, sometimes no, I’ll explain. Over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aids are a category of hearing devices established by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2022 (U.S. Food & Drug Administration, 2022). These devices fall into three subcategories:

- FDA-registered pre-set OTC hearing aids, which are limited- or non-customizable.

- FDA-cleared self-fitting OTC hearing aids, which allow users to adjust settings based on their hearing needs.

- FDA-cleared hearing aid feature (i.e., Apple AirPod Pro 2 coupled with iPhone software).

In contrast, direct-to-consumer (DTC) hearing devices represent a broader category. This includes OTC hearing aids as well as other products such as personal sound amplification products (PSAPs) and hearables—all of which are sold directly to consumers without involving a licensed professional.

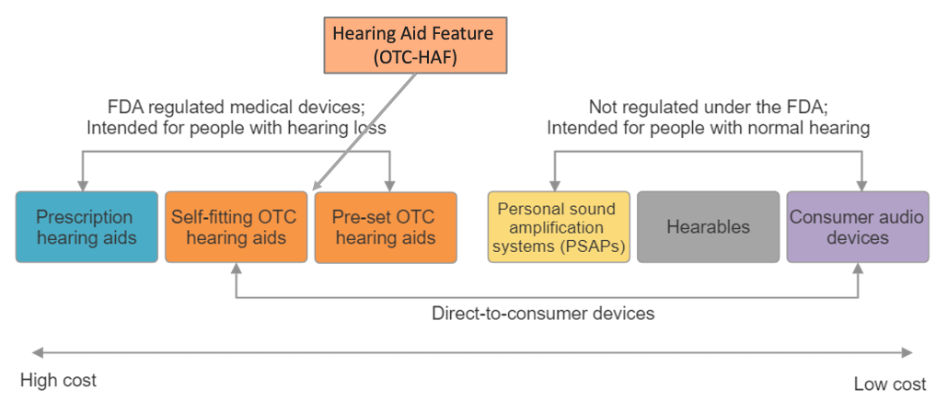

Before the FDA established the OTC category, the term “DTC” was often used to describe both hearing devices and the service delivery model used to access them (Manchaiah et al., 2017; Tran & Manchaiah, 2018). However, today it is more appropriate to use the specific device categories (see Figure 1) when referring to product types and reserve the term “DTC” for describing the mode of delivery—that is, how hearing care is accessed, not what the device is.

Q2. So, where do all these devices fall within the broader categories of hearing devices available in the U.S. market today? And how are they different from traditional hearing aids?

Great question! With so many emerging device types, it can definitely feel overwhelming. That said, we now have a much clearer understanding than we did just a couple of years ago—especially since the introduction of OTC hearing aids.

Let’s look at Figure 1 (adapted from Manchaiah et al., 2023a), which helps illustrate the spectrum of hearing device categories in today’s U.S. market. On one end of the continuum, we see prescription hearing aids, and on the other, consumer audio devices—two categories which most people understand.

In between, the landscape gets more nuanced. Sitting next to prescription hearing aids are OTC hearing aids, which include both self-fitting and pre-set models. Moving further along are PSAPs and hearables, followed by general consumer audio devices.

All devices shown in this Figure—except prescription hearing aids—can be distributed through DTC channels. However, some restrictions apply for OTC devices, depending on the specific subcategory. For example:

- Devices under the QDD (qualified direct distribution) category can be sold online.

- Devices under the QUC (qualified unrestricted channels) category can be sold both online and in retail stores.

It's important to understand that, while there is some overlap in features and functionality, devices generally decrease in hearing enhancement technology and cost as you move from prescription hearing aids toward consumer audio products.

Figure 1: Hearing device categories in the U.S. market (adapted from Manchaiah et al., 2023a).

Q3. Who are OTC hearing aids intended for, and what kind of hearing loss do they typically address?

OTC hearing aids are intended for adults (18 years and older) with perceived mild-to-moderate hearing loss (U.S. Food & Drug Administration, 2022). These devices are sold directly to consumers without the need for professional consultation, audiological testing, or medical evaluation. They are best suited for individuals with bilateral, stable, age- or noise-related sensorineural hearing loss that has developed gradually over time.

OTC hearing aids are designed to make hearing support more accessible and affordable, especially for people who notice difficulties such as:

- Frequently turning up the volume on the TV,

- Struggling to follow group conversations, or

- Often asking others to repeat themselves.

These individuals may recognize they have hearing challenges but are not yet ready to seek professional hearing care or do not have insurance coverage.

Q4. Why do you think consumers are increasingly exploring these OTC hearing aid options?

I believe there are several reasons behind the growing interest in OTC hearing aids. Cost is certainly a major factor—many insurance plans do not cover hearing aids. Even when they do, the coverage is often minimal (e.g., a $500 reimbursement), which doesn’t significantly reduce out-of-pocket expenses. But beyond cost, convenience also plays a key role. OTC hearing aids can appeal to individuals who are not yet ready to take the bigger step of consulting a hearing healthcare professional. These consumers often want a solution that is quick, easy to access, and doesn’t require appointments or testing. Interestingly, OTC devices are sometimes purchased by significant others—such as spouses or adult children—as a gift for someone experiencing hearing difficulties, as noted in consumer research and reviews (Manchaiah et al., 2019). In many ways, I see OTC hearing aids as a starting point in the broader hearing care journey—much like how people might begin with reading glasses before moving on to prescription eyewear.

Q5. Did the introduction of the OTC category actually lead to more people using hearing aids overall?

Two competing viewpoints existed during the time the OTC hearing aid category was being developed. On one hand, policymakers hoped that these devices would improve affordability and accessibility, especially for individuals who lacked insurance coverage or access to traditional hearing care. The expectation was that more people—particularly those early in their hearing loss journey—would begin using hearing devices. On the other hand, some hearing care professionals and traditional hearing aid manufacturers expressed concerns that OTC devices might cut into the existing prescription hearing aid market.

Now that we’re three years in, here’s what we know:

- We see no evidence of a decline in prescription hearing aid sales. In fact, the overall market continues to grow steadily, as expected (Strom, 2023).

- OTC hearing aid sales data are not publicly available, making it difficult to assess market trends comprehensively. However, based on conversations with industry colleagues, we have observed the following:

- Pre-set OTC hearing aids, which are generally lower in cost, appear to be selling in higher volumes than the more advanced self-fitting OTC devices.

- Internal data from some traditional manufacturers indicate that OTC hearing aid users are on average 7–10 years younger than those purchasing prescription devices.

- Return rates for OTC hearing aids are relatively high—ranging anywhere from 30% to 70%, depending on the product and dispensing channel.

- According to MarkeTrak data, hearing aid adoption has increased from 30.2% in 2015 to 39.1% in 2025 (Dobyan, 2025). Moreover, people are also seeking help sooner, with the average time from noticing hearing difficulties to seeing a professional dropping from 4 years to 3 years.

In my own clinical experience, I’ve encountered many patients who initially tried OTC hearing aids but later sought professional help and opted for prescription devices instead. That said, we still lack concrete evidence to determine whether the OTC category has significantly increased overall hearing aid adoption rates. So, while there are encouraging signs and anecdotal insights, we can’t definitively say how much of an impact this new category has had just yet.

Q6. Is there solid research backing the effectiveness of these OTC hearing aids?

We have seen a number of studies published over the last two to three years that provide insights into the feasibility, efficacy, and—to some extent—the effectiveness of OTC hearing aids as well as DTC service delivery models. The earliest study on an OTC hearing aid currently available on the market came from Bose Corporation in collaboration with Northwestern University (Sabin et al., 2020). This study looked at outcomes for the same device when it was self-fit by the users themselves versus fitted by an audiologist, finding comparable results. These findings were used to obtain De Novo status for self-fitting hearing aids from the FDA (i.e., a classification which assumes a reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness in the absence of a similar device for comparison). Since then, other OTC hearing aid manufacturers who needed data for 510k (i.e., pre-market) approval have followed the same approach, showing that self-fitting is comparable to audiologist fitting with the same device (Baltzell et al., 2025; De Sousa et al., 2023, 2024; Sheng et al., 2024), with similar outcomes supporting efficacy. Shortly after the FDA ruling, we conducted an observational survey study and found that self-fitting hearing aids can produce outcomes comparable to those reported by prescription hearing aid users (Swanepoel et al., 2023), although no controlled studies have directly compared prescription versus OTC devices. Additional research has shown that differences between self-fitting algorithms in OTC devices are marginal (Knoetze et al., 2024), that usability and performance are generally comparable across self-fitting OTC hearing aids (Knoetze et al., 2025a), and that the gain provided by these devices is about 10 dB below NAL-NL2 prescription targets for mild-to-moderate hearing loss (Knoetze et al., 2025b). Overall, most OTC hearing aid research has focused on high-priced, relatively high-tech self-fitting devices.

In contrast, very little is known about the outcomes of preset OTC hearing aids, which are generally lower-priced and lower-tech. A recent study found that these pre-programmed devices have limited ability to improve communication for individuals with mild-to-moderate hearing loss (Szatkowski & Souza, 2025). Our recent feasibility study in a remote South African community showed that preset OTC hearing aids, when distributed through community health workers, can produce acceptable outcomes (Mothemela et al., 2025). The limited research in this area may be largely due to the FDA not requiring preset OTC hearing aids to undergo 510(k) clearance or provide clinical trial data.

Independent research on the Apple Hearing Aid Feature (HAF) is also scarce. Publicly available clinical trial data from Apple, which used a design similar to that of self-fitting OTC hearing aids, showed no difference between self-fitting and audiologist fitting methods (Apple, 2024). Our recent study demonstrated that the Apple Hearing Test Feature (HTF) had good accuracy and test–retest reliability when compared to gold standard hearing testing in a sound booth (Knoetze et al., 2025c), but that the HAF tended to underfit compared to NAL-NL2 targets and offered no measurable benefit in speech-in-noise performance under laboratory conditions (Knoetze et al., 2025d).

Clinical trials from Indiana University (Humes et al., 2017, 2019), Northwestern University (Humes et al., 2025), and from the University of Iowa (Wu et al., 2025), have provided valuable insights into the OTC hearing aid service delivery model. While these controlled trials are highly reliable, their designs limit external validity as most of these studies used de-featured prescription hearing aids to simulate OTC hearing aids rather than using OTC hearing aids in the current market.

Some recent and emerging research on other aspects of OTC hearing aids is also available, including how they are communicated in the media (Champlin et al., 2025), how consumers navigate the online journey when considering these devices (Katz et al., 2025), the accessibility of health information and product labeling (Shah et al., 2024; Singh et al., 2025), and analyses of consumer reviews (Conway et al., 2025; Knoetze et al., 2025e; Stolyar et al., 2025).

You can refer to a recent AudiologyOnline article that provides a critical summary of research on OTC hearing aids (Taylor & Mueller, 2025).

Q7. Are there certain types of patients who tend to do particularly well—or poorly—with OTC hearing aids?

While there is still limited research on this topic, several ongoing studies are actively exploring it. Early findings from institutions such as the University of Iowa and Vanderbilt University Medical Center suggest that successful OTC hearing aid outcomes are influenced by a combination of factors—including self-perceived hearing loss severity, cognitive function, and lifestyle characteristics (Ricketts et al., 2024). Specifically, individuals with mild-to-moderate, self-identified hearing loss, good cognitive abilities, and active, engaged lifestyles are more likely to experience positive outcomes when using OTC hearing aids (Ricketts et al., 2024). Additional factors such as finger dexterity and realistic hearing aid expectations also play an important role in determining success.

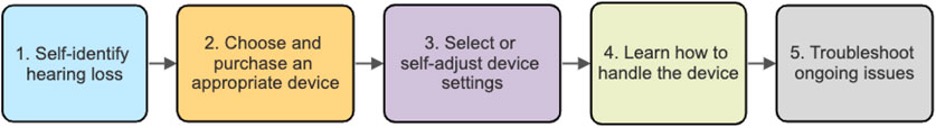

Although direct evidence for OTC outcomes is still emerging, we can draw reasonable inferences from broader hearing aid research. Figure 2 highlights the key consumer characteristics and behaviors that are likely to support successful OTC hearing aid use, particularly within a journey that involves self-assessment and self-management (Manchaiah et al., 2023a).

Some consumer traits that could make a good OTC candidate:

• Self-motivation and a proactive attitude toward managing hearing needs.

• Comfort with technology and ability to use smartphones or apps for device adjustments

• Acknowledgment and acceptance of hearing difficulties.

• Interest in a lower-cost, entry-level solution before seeking professional care and have realistic expectations from these devices.

Individuals with more severe hearing loss, unilateral or progressive conditions, or underlying medical issues may not be good candidates for OTC hearing aids. These devices generally lack the amplification needed for severe hearing loss (Knoetze et al., 2025b) and require a certain level of tech-savviness for setup and use. In such cases, professional evaluation and prescription hearing aids are recommended for better outcomes.

Figure 2: Pre-requisites for successful use of OTC hearing aids along the consumer journey (Manchaiah et al., 2023a).

Q8. What are the biggest risks or challenges someone might face with an OTC hearing aids or DTC service delivery model?

We have so many hearing device categories on the market, which can be extremely confusing for patients. Often, other device types (e.g., PSAPs, hearables) are inappropriately or mistakenly marketed or sold as OTC hearing aids (Conway et al., 2025). In addition, most consumers are unaware of the differences between pre-set and self-fitting OTC hearing aids, making the purchasing process even more complicated. There is also high variability in audio performance and build quality across OTC devices—especially at the lower price points (Manchaiah et al., 2024a, 2025a). As a result, people may end up with very good or very poor-quality devices, depending on their research and shopping behavior.

Other potential risks include underestimating the severity of hearing loss (Hamburger et al., 2025), overlooking underlying medical conditions (e.g., unilateral hearing loss), and issues with device fit and usability (Cho et al., 2025; Lu & Jeyakumar, 2024). All of these factors can lead to reduced benefit and satisfaction, which may ultimately result in high return rates for these devices.

Q9. You talked about variability in device quality. Can you expand on that?

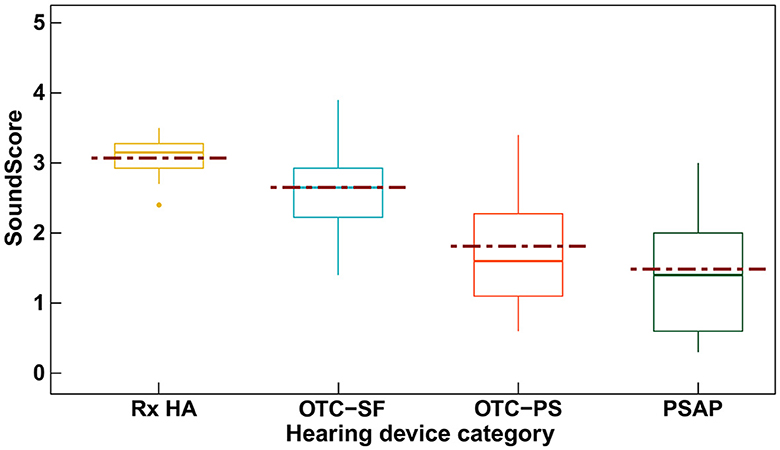

We know from previous research on PSAPs in terms of electroacoustic testing and simulated gain measurements that lower cost devices may have poor acoustics quality (Callaway & Punch, 2008; Chen & McPhearson, 2015). It appears that this also true for OTC hearing aids. A recent initiative by the Hear Advisor (www.hearadvisor.com) developed a new testing methodology which results in a consumer centric metric referred to as “SoundScore” (Manchaiah et al., 2024a). This metric provides a single number for consumers to understand the audio performance of a hearing device. Hear Advisor colleagues have tested over 70 hearing devices including prescription hearing aids, OTC hearing aids and PSAPs. The SoundScore ranges from 1 to 5 with higher score indicating better audio performance. We recently analyzed these data to compare differences between device categories as illustrated in Figure 3 (Manchaiah et al., 2024a, 2025a).

The study shows that hearing device quality varies widely by category, fitting method, and price. The prescription hearing aids consistently outperformed OTC and PSAP devices, with performance further boosted when professionally tuned. Inexpensive devices (< USD 500) generally had poor sound quality, while mid-priced models (USD 500–1,000) showed mixed results, and devices above USD 1,000 delivered consistently good—but not proportionally better—performance. This highlights that both technology type and fitting approach drive quality, and price alone is not a guarantee of superior sound.

Figure 3: SoundScore variations among hearing device categories (Manchaiah et al., 2024a).

Q10. Is there a way consumers can ensure a better-quality device with lower price?

Self-fitting OTC hearing aids generally show less variability, giving consumers a reasonable chance of getting good technology and usable gain. In contrast, preset OTC hearing aids have much higher variability, as shown in Figure 3. To improve the chances of selecting a quality device, consumers can: (1) check detailed testing and recommendations from the HearAdvisor website, though not all devices have been tested; (2) review independent resources such as the National Council on Aging, Consumer Reports, and American Associations of Retired Persons (AARP), which list top OTC hearing aids based on expert input and consumer feedback; and (3) consider verified consumer reviews on platforms like Amazon, while being cautious of potentially inflated reviews on manufacturers’ websites. Finally, it’s important to choose a device with a good return policy, use it thoroughly during the trial period, and return it if it does not provide sufficient benefit.

Q11. If price is a concern, Apple devices are cheaper, and you mentioned earlier that there is some early research on them. Could they be a good option for consumers who want a quality device at a lower cost?

Yes, Apple devices are generally more affordable and fall within the preset OTC hearing aid category. However, they also include some features and functionalities similar to self-fitting OTC hearing aids, making them a viable option for many users. There are a few considerations, though. First, users must own an iPhone—purchasing one solely for the hearing feature, along with AirPods Pro 2, could be costly. Second, the AirPods’ form factor may not be comfortable for all-day wear, and the battery life may not last an entire day, making them better suited for situational rather than continuous use.

Q12. Do any of the companies that sell OTC hearing aids provide follow-up support or customer service?

Most OTC hearing aid manufacturers offer some form of technical support, mainly through customer service to help troubleshoot common issues. It is unclear whether call center agents are specifically trained for both sales and support. Many companies (e.g., Sony, Lexie) use a two-tiered system: initial calls are handled by technicians, and unresolved issues are escalated to audiologists for further assistance.

I believe OTC hearing aids will continue to improve, even in lower price ranges. However, what may truly set companies apart is the quality and efficiency of their customer service—especially since many users are middle-aged or older adults who may struggle with handling, technical, or sound quality issues that they cannot resolve on their own.

Q13. Can teleaudiology play a role in supporting people using these devices remotely?

Yes, teleaudiology can play an important role. It enables consumers to connect with hearing care professionals via phone or video calls for help with fitting, troubleshooting, and effective use. This is especially valuable for older adults or those in rural areas who may not have easy access to in-person care. While not all OTC companies currently offer this service, integrating teleaudiology could greatly improve user experience and long-term outcomes.

Companies such as Jabra Enhance and Hear.com have made notable progress in this area by creating a teleaudiology pathway that supports the entire hearing care journey, including assessment, fitting, and aftercare. Audiologists who work with hearing aids also have the opportunity to adapt or replicate such models to provide care for both prescription and OTC hearing aid users where feasible.

Q14. Is the remote care really adequate for new OTC hearing aid users?

You make a good point about the limitations of remote care. Existing research suggests that while some users can receive adequate support through remote models across the hearing care journey, others may prefer in-person or hybrid options, the latter is where they can see a provider in person for certain aspects. For example, after a hearing aid fitting, it can be difficult to confirm proper insertion in the ear canal remotely. Similarly, if users report sound quality issues (e.g., static from internal noise) or feedback, diagnosing the problem remotely can be challenging. For this reason, hybrid care can be appealing. However, I am not aware of any OTC manufacturers currently offering such options.

This presents an opportunity for audiologists to create care packages that include remote, in-person, and hybrid models, allowing any hearing aid user—including OTC users—to seek professional support. Audiologists can charge for their time and expertise, adding value to the user’s hearing care journey and continuing care as users transition to prescription hearing aids.

Q15. At first glance, OTC hearing aids seem more affordable—but do the costs add up over time if users need professional help?

You’re right, OTC hearing aids may seem more affordable—but the costs can add up over time if users need professional help. Industry data shows that return rates for OTC devices are high (over 30%), often due to sound quality issues, handling difficulties, and customer service challenges. This means some consumers spend a great deal of time researching, learning to fit and handle the devices, and troubleshooting problems. If we factor in this time as part of the cost, some users may actually end up spending more in the long run. High-end self-fitting OTC hearing aids priced around $800 may also feel expensive when compared to big-box retailers and audiologists who offer hearing care packages just over $1,000, with professional services included. Ultimately, whether OTC devices are truly cost-effective depends not only on the price of the device but also on how much consumers value their time, the level of support they require, and their likelihood of needing professional care along the way.

Q16. How are audiologists adapting to this shift? Are they generally supportive of OTC devices, or more cautious?

When the OTC hearing aid category was first introduced, many hearing healthcare professionals expressed negative views, as shown in one of our surveys (Manchaiah et al., 2023b). This was likely due to concerns that OTC devices might cut into their business. However, prescription hearing aid sales have not been significantly affected, and if there is any impact, it appears to be small. In fact, media coverage of OTC devices has raised awareness about hearing health, and the broader DTC movement may even be encouraging earlier adoption of hearing devices. As a result, audiologists no longer seem to view OTC hearing aids as a major threat.

In terms of adapting, the original idea was that audiologists could sell OTC devices and provide support for users experiencing difficulties. While some clinics—especially within certain medical centers—have pursued this model, it does not appear that large numbers of audiologists are currently offering these products or services.

Q17. Do you think OTC hearing aids are helping to reach populations that haven’t traditionally accessed hearing care?

OTC hearing aids were designed to be self-fit and self-managed, aiming to increase access for a wide range of users. Early indications suggest that OTC users tend to be younger, potentially creating a new market among this group. The DTC model has also decoupled device sales from services—often, significant others purchase the devices, and only later does the person with hearing loss seek professional support (Taylor & Manchaiah, 2019). However, there is no clear evidence yet that these devices are expanding access to harder-to-reach populations, such as those in rural areas.

In the past two years, new companies and devices have emerged, with growing distribution through online platforms and big-box stores. Still, distribution channels need further development, and access should also extend to settings such as primary care, pharmacies, community-based programs, and volunteer-supported care (Manchaiah et al., 2024b). That said, recent surveys show awareness, interest, and readiness among healthcare professionals—including primary care providers (Davis et al., 2025) and pharmacists (Midey et al., 2022)—remain low, indicating more work is needed to build these pathways.

Some exciting work is being conducted at the University of Pretoria (Frisby et al., 2022, 2024; Mothemela et al., 2025), Johns Hopkins University (Nieman et al., 2022), and the University of Alabama (Hay-McCutcheon et al., 2024), exploring the use of OTC hearing aids in remote populations through community-based approaches. Such models have strong potential to expand access for individuals who face challenges in obtaining professionally fitted devices.

Q18. What should I say to a patient who comes to me with questions about a OTC hearing aid or PSAP they bought online?

How you respond really depends on your comfort level as an audiologist and the specific concerns the patient brings in. Even if you are unfamiliar with a particular model, it is often easy to review the company website or device manual to understand its intended use and appropriateness for the patient’s hearing loss. You can also perform electroacoustic testing to evaluate the device’s audio performance and use real-ear measures to assess whether it provides adequate gain for the individual’s hearing needs. Beyond the device itself, you can provide diagnostic services, counseling, and aftercare support that patients are unlikely to get elsewhere.

The key is to offer a balanced perspective—discuss both the potential benefits and the limitations of these devices. By doing so, you build trust and ensure that patients see you as a partner in their care, whether they continue with OTC devices or eventually transition to prescription hearing aids.

For additional guidance, I encourage you to review recent articles that outline strategies for integrating OTC hearing aids into clinical practice (Reed, 2025) and highlight the role audiologists can play in supporting patients along their OTC journey (Ricketts, 2025).

Q19. What are the biggest unanswered questions in the research about OTC and DTC hearing care?

We still know relatively little about OTC hearing aids and DTC service delivery models. Our recent publications and working groups have highlighted several important unanswered questions (Manchaiah et al., 2023a; National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, 2024), including:

• Who are good (or not so good) candidates for OTC hearing aids and DTC models, and how best can we support them?

• Is there added benefit or greater satisfaction with incremental technology and professional services (Manchaiah et al., 2025b)?

• How can we better understand and promote auditory wellness using self-assessment tools, and how can we encourage self-management, particularly among middle-aged and older adults (Humes et al., 2024)?

To address these questions, we have launched a multi-center effectiveness trial called IHAT (Innovations in Hearing Aid Technology) at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and the University of Colorado Boulder. This four-arm randomized controlled trial assigns participants to: (a) prescription hearing aids fitted by an audiologist (gold standard), (b) OTC hearing aids with in-person audiologist support, (c) OTC hearing aids with remote audiologist support, or (d) self-fit OTC hearing aids without professional support.

We are evaluating outcomes using a multidimensional approach, including self-reported measures, behavioral assessments, cognitive testing, and neurophysiological measures (P300). This will allow us to examine not only how technology and service delivery models influence outcomes, but also whether appropriately fitted and supported hearing care can produce measurable changes in the brain in addition to improvements in daily functioning. To date, around 60 participants have been enrolled, and the trial is expected to be completed within the next three years.

Q20. Looking ahead, how do you think the role of audiologists will evolve as the OTC market continues to grow?

That’s an excellent question, and one I reflect on often. OTC hearing aids and DTC service delivery models are here to stay. The key questions are how large a share of the market they will capture, and which patients are best suited for them. Regardless, audiologists will need to coexist with these devices and models.

I believe that as long as audiologists continue to “add value” to patient care, our profession will not only remain relevant but will thrive. To do this, we must carefully define our role and focus our efforts where we make the greatest impact. For example, we should prioritize developing and refining diagnostic protocols to ensure medical and audiological issues are identified early and accurately. We can also design rehabilitation strategies that move beyond a one-size-fits-all model, providing tailored solutions for individuals with mild to severe hearing difficulties.

This may require decoupling professional services from device sales and placing more emphasis on service delivery, counseling, and long-term care (Taylor & Manchaiah, 2019). Additionally, with the potential for future pharmacological agents to complement devices and rehabilitation strategies, audiologists will be uniquely positioned to integrate these treatments into holistic hearing care.

Overall, the prospects for the profession are strong. If we remain adaptable and keep patient-centered care at the core of what we do, the growth of the OTC market can be an opportunity to redefine and expand the value audiologists bring to hearing health.

References

Apple. (2024). Using AirPods Pro 2 with iPhone and iPad to Help Protect, Assess, and Assist Hearing. Retrieved from: https://www.apple.com/au/health/pdf/Hearing_Health_Features_on_AirPods_Pro_2_October_2024.pdf (accessed on July 11, 2025).

Baltzell, L. S., Kokkinakis, K., Li, A., Yellamsetty, A., Teece, K., & Nelson, P. B. (2025). Validation of a Self-Fitting Over-the-Counter Hearing Aid Intervention Compared with a Clinician-Fitted Hearing Aid Intervention: A Within-Subjects Crossover Design Using the Same Device. Trends in Hearing, 29, 23312165251328055. https://doi.org/10.1177/23312165251328055

Callaway, S. L., & Punch, J. L. (2008). An electroacoustic analysis of over-the-counter hearing aids. American Journal of Audiology, 17(1), 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1044/1059-0889(2008/003)

Champlin, S., Miller, S., Griffith, A., Hatley, A., Reed, C., & Schafer, E. (2025). Opening Access but Concealing Contact: A First Study of Over-The-Counter Hearing Aid Consumer-Facing Communications. Health Communication, 40(5), 848–855. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2024.2375146

Chan, Z. Y., & McPherson, B. (2015). Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids: A Lost Decade for Change. BioMed Research International, 2015, 827463. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/827463

Cho, J. W., Tandadjaja, O., Henriks, C., Jamal, M., Hori, K., Feier, J., Russel, Z., Lawrence, E., Greene, N., & Choi, J. S. (2025). Understanding Public Perception of Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids: A Sentiment and Thematic Analysis of Consumer Reviews. OTO Open, 9(2), e70131. https://doi.org/10.1002/oto2.70131

Conway, K., Knoetze, M., Swanepoel, D.W., Nassiri, A., Sharma, A., & Manchaiah, V. (2025). Marketing practices and information quality for OTC hearing aids on Amazon.com. Under Review.

Davis, R. J., Lin, M., Ayo-Ajibola, O., Ahn, D. D., Brown, P. A., Parsons, J., Ho, T. F., & Choi, J. S. (2025). Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids: A Nationwide Survey Study to Understand Perspectives in Primary Care. The Laryngoscope, 135(1), 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.31689

De Sousa, K. C., Manchaiah, V., Moore, D. R., Graham, M. A., & Swanepoel, W. (2023). Effectiveness of an Over-the-Counter Self-fitting Hearing Aid Compared With an Audiologist-Fitted Hearing Aid: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Otolaryngology-- Head & Neck Surgery, 149(6), 522–530. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2023.0376

De Sousa, K. C., Manchaiah, V., Moore, D. R., Graham, M. A., & Swanepoel, W. (2024). Long-Term Outcomes of Self-Fit vs Audiologist-Fit Hearing Aids. JAMA Otolaryngology-- Head & Neck Surgery, 150(9), 765–771. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2024.1825

Dobyan, B. (2025). 20Q: Interpreting the Hearing Health Landscape through MarkeTrak - From Insight to Impact. Retrived from: https://www.audiologyonline.com/articles/20q-interpreting-hearing-health-landscape-29350 (accessed on September 07, 2025).

Frisby, C., Eikelboom, R. H., Mahomed-Asmail, F., Kuper, H., de Kock, T., Manchaiah, V., & Swanepoel, W. (2022). Community-based adult hearing care provided by community healthcare workers using mHealth technologies. Global health action, 15(1), 2095784. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2022.2095784

Frisby, C., De Sousa, K. C., Eikelboom, R. H., Mahomed-Asmail, F., Moore, D. R., de Kock, T., Manchaiah, V., & Swanepoel, W. (2024). Smartphone-Facilitated In-Situ Hearing Aid Audiometry for Community-Based Hearing Testing. Ear and hearing, 45(4), 1019–1032. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000001496

Hamburger, A., Whitehead, R., & Michaelides, E. (2025). Misjudgments of Hearing Loss and Its Implications for Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids. OTO open, 9(2), e70101. https://doi.org/10.1002/oto2.70101

Humes, L. E., Rogers, S. E., Quigley, T. M., Main, A. K., Kinney, D. L., & Herring, C. (2017). The Effects of Service-Delivery Model and Purchase Price on Hearing-Aid Outcomes in Older Adults: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. American journal of audiology, 26(1), 53–79. https://doi.org/10.1044/2017_AJA-16-0111

Humes, L. E., Kinney, D. L., Main, A. K., & Rogers, S. E. (2019). A Follow-Up Clinical Trial Evaluating the Consumer-Decides Service Delivery Model. American Journal of Audiology, 28(1), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_AJA-18-0082

Humes, L. E., Dhar, S., Manchaiah, V., Sharma, A., Chisolm, T. H., Arnold, M. L., & Sanchez, V. A. (2024). A Perspective on Auditory Wellness: What It Is, Why It Is Important, and How It Can Be Managed. Trends in Hearing, 28, 23312165241273342. https://doi.org/10.1177/23312165241273342

Humes, L. E., Dhar, S., Meskan, M., Pitman, A., & Singh, J. (2025). A Multisite Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing the Effectiveness of Two Self-Fit Methods to the Best-Practices Method of Hearing Aid Fitting. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 68(4), 2080–2103. https://doi.org/10.1044/2024_JSLHR-24-00423

Katz, J., Mormer, E., Parthasarathy, A., Bharadwaj, H., Wang, Y., & Palmer, C. (2025). Sound Advice: A Consumer's Perspective on Navigating the World of Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids. Seminars in Hearing, 46(1), 40–52. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0045-1806805

Knoetze, M., Manchaiah, V., De Sousa, K., Moore, D. R., & Swanepoel, W. (2024). Comparing Self-Fitting Strategies for Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids: A Crossover Clinical Trial. JAMA Otolaryngology-- Head & Neck Surgery, 150(9), 784–791. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2024.2007

Knoetze, M., Manchaiah, V., & Swanepoel, W. (2025a). Usability and Performance of Self-Fitting Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 36(1), 23–36. https://doi.org/10.3766/jaaa.240037

Knoetze, M., Manchaiah, V., Cormier, K., Schimmel, C., Sharma, A., & Swanepoel, W. (2025b). Gain Analysis of Self-Fitting Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids: A Comparative and Longitudinal Analysis. Audiology Research, 15(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15010017

Knoetze, M., Manchaiah, V., & Swanepoel, D.W. (2025c). Apple Hearing Test Feature for AirPods Pro 2: Accuracy, reliability and time-efficiency. Under Review.

Knoetze, M., Manchaiah, V., & Swanepoel, D.W. (2025d). Apple AirPods Pro 2 self-fitting hearing aid (OTC-SF) hearing aid feature. Under Review.

Knoetze, M., Manchaiah, V., Oosthuizen, I., Ratinaud, P., & Swanepoel, D.W. (2025e). Consumer perspectives on over-the-counter self-fitting hearing aids. A mixed-methods study of Amazon reviews. Under preparation.

Lu, Q., & Jeyakumar, A. (2024). A Retrospective Study of the Adverse Events Associated With Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids in the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) Database. Cureus, 16(10), e72491. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.72491

Manchaiah, V., Taylor, B., Dockens, A. L., Tran, N. R., Lane, K., Castle, M., & Grover, V. (2017). Applications of direct-to-consumer hearing devices for adults with hearing loss: a review. Clinical interventions in aging, 12, 859–871. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S135390

Manchaiah, V., Amlani, A. M., Bricker, C. M., Whitfield, C. T., & Ratinaud, P. (2019). Benefits and Shortcomings of Direct-to-Consumer Hearing Devices: Analysis of Large Secondary Data Generated From Amazon Customer Reviews. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 62(5), 1506–1516. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_JSLHR-H-18-0370

Manchaiah, V., Swanepoel, W., & Sharma, A. (2023a). Prioritizing research on over-the-counter (OTC) hearing aids for age-related hearing loss. Frontiers in Aging, 4, 1105879. https://doi.org/10.3389/fragi.2023.1105879

Manchaiah, V., Sharma, A., Rodrigo, H., Bailey, A., De Sousa, K. C., & Swanepoel, W. (2023b). Hearing Healthcare Professionals' Views about Over-The-Counter (OTC) Hearing Aids: Analysis of Retrospective Survey Data. Audiology Research, 13(2), 185–195. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres13020018

Manchaiah, V., Taddei, S., Bailey, A., Swanepoel, D.W., Rodrigo, H., & Sabin, A. (2024a). A novel consumer-centric metric for hearing device audio performance. Frontiers in Audiology and Otology, 2:1406362. https://doi.org/10.3389/fauot.2024.1406362

Manchaiah, V., Nassiri, A., Sharma, A., Dhar, S., Humes, L., & Swanepoel, D.W. (2024b). Emerging care pathways for managing adult hearing loss. The Hearing Journal, 78(2), 4-6. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.HJ.0001098604.92313.15

Manchaiah, V., Taddei, S., Bailey, A., Swanepoel, W., Rodrigo, H., & Sabin, A. (2025a). How Much Should Consumers with Mild to Moderate Hearing Loss Spend on Hearing Devices? Audiology Rresearch, 15(3), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15030051

Manchaiah, V., Dhar, S., Humes, L., Sharma, A., Taylor, B., & Swanepoel, W. (2025b). Is There Incremental Benefit with Incremental Hearing Device Technology for Adults with Hearing Loss?. Audiology research, 15(3), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15030052

Midey, E. S., Gaggini, A., Mormer, E., & Berenbrok, L. A. (2022). National Survey of Pharmacist Awareness, Interest, and Readiness for Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids. Pharmacy (Basel, Switzerland), 10(6), 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10060150

Mothemela, B., Frisby, C., Mahomed-Asmail, F., de Kock, T., Moore, D., Manchaiah, V., & Swanepoel, D.W. (2025). Community-based hearing aid fitting model for adults in low-income communities facilitated by community health workers: A feasibility study. Global Health Action, In Press. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2025.2545630

Mueller, H. G., & Taylor, B. Research Quick Takes, volume 10: An update on OTC hearing aids. AudiologyOnline, Article 29477. Available at www.audiologyonline.com

National Institute of Deafness and other Communication Disorders (2024). Working Group on Accessible and Affordable Hearing Health Care for Adults. Retrieved from: https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/workshops/2024/working-group-on-accessible-and-affordable-hearing-health-care-for-adults/summary (accessed on Aug 16, 2025).

Reed M. (2025). Integrating OTC Hearing Aids into Audiology Clinics. Seminars in Hearing, 46(1), 34–39. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0045-1806796

Ricketts, T, Stangl, E., Branscome, K., Oleson, J., &. Wu, Y. (2024). Patient Factor Predictors of Hearing Aid Service Level-Based Outcomes. Podium Presentation, American Auditory Society Meeting: Scottsdale, AZ

Ricketts T. A. (2025). Potential Roles of Audiologists Supporting Patients' OTC Hearing Aid Journey. Seminars in Hearing, 46(1), 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0045-1806791

Sabin, A. T., Van Tasell, D. J., Rabinowitz, B., & Dhar, S. (2020). Validation of a Self-Fitting Method for Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids. Trends in Hearing, 24, 2331216519900589. https://doi.org/10.1177/2331216519900589

Shah, V., Lava, C. X., Hakimi, A. A., & Hoa, M. (2024). Evaluating Quality, Credibility, and Readability of Online Over-the-Counter Hearing Aid Information. The Laryngoscope, 134(7), 3302–3309. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.31278

Sheng, T., Pasquesi, L., Gilligan, J., Chen, X. J., & Swaminathan, J. (2024). Subjective benefits from wearing self-fitting over-the-counter hearing aids in the real world. Frontiers in neuroscience, 18, 1373729. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2024.1373729

Singh, J., Johnston, E., & Dhar, S. (2025). Comprehension and Use of the Over-the-Counter Hearing Aid Product Information Label. Seminars in hearing, 46(1), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0045-1806804

Stolyar, A., Katz, J., Dymowski, C., Lyons, T., Parthasarathy, A., Bharadwaj, H., Mormer, E., Palmer, C., & Wang, Y. (2025). Content Analysis of Over-the-Counter Hearing Aid Reviews. AMIA Joint Summits on Translational Science proceedings. AMIA Joint Summits on Translational Science, 2025, 546–555.

Storm, K. (2023). The sound of growth: Hearing aid sales strong in Q2 2023 as market normalize. Retrieved from:

https://www.hearingtracker.com/pro-news/hearing-aid-sales-strong-in-q3-2023-as-markets-return-to-normal-growth (accessed on Aug 12, 2025).

Swanepoel, W., Oosthuizen, I., Graham, M. A., & Manchaiah, V. (2023). Comparing Hearing Aid Outcomes in Adults Using Over-the-Counter and Hearing Care Professional Service Delivery Models. American journal of audiology, 32(2), 314–322. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_AJA-22-00130

Szatkowski, G., & Souza, P. E. (2025). Evaluation of Communication Outcomes With Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids. Ear and Hearing, 46(3), 653–672. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000001608

Taylor, B. & Manchaiah, V. (2019). Pathways to Care: How innovations are decoupling professional services from the sale of hearing devices? Audiology Today, 31(5), 16-24.

Taylor B, Mueller HG. (2025). Research Quick Takes Volume 10: An update on OTC hearing aids. Retrieved from AudiologyOnline.

Tran, N. R., & Manchaiah, V. (2018). Outcomes of Direct-to-Consumer Hearing Devices for People with Hearing Loss: A Review. Journal of Audiology & Otology, 22(4), 178–188. https://doi.org/10.7874/jao.2018.00248

U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (2022). FDA finalizes historic rule enabling access to over-the-counter hearing aids for millions of Americans. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-finalizes-historic-rule-enabling-access-over-counter-hearing-aids-millions-americans

Wu, Y. H., Stangl, E., Branscome, K., Oleson, J., & Ricketts, T. (2025). Hearing Aid Service Models, Technology, and Patient Outcomes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery, 151(7), 684–692. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2025.1008

Citation

Manchaiah, V. (2025). 20Q: Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids and Service Delivery Models—What We Know, and What Remains Unclear. AudiologyOnline, Article 29357. Available at www.audiologyonline.com