Beyond Good, Better, Best: How “New Generation” Features and Algorithms are Changing the Hearing Aid Selection Process

Twenty twenty-three was a landmark year for hearing aid pioneer Signia, and in 2024 they plan to build on it. In addition to launching the innovative IX platform in 2023, Signia opened a new manufacturing facility and corporate headquarters; and they made significant investments in sales support, IT, and system structures that will pay huge dividends in 2024 and beyond for providers and wearers alike. And the folks at Signia say, stay tuned! There are more great things happening in 2024, as they are launching some exciting new additions to their groundbreaking IX platform soon.

A few weeks ago, Audiology Online sat down with Brian Taylor, senior director of audiology at Signia. The topic of their chat was how recent wearer preference studies can be applied to the hearing aid selection process, and specifically, how hearing care professionals can leverage those research findings to recommend Signia’s 7IX with Real Time Conversation Enhancement (RTCE), their premium level IX device, to more patients -- and make this recommendation with added confidence and assurance.

AudiologyOnline: I can see from the title of our interview that the popular approach to differentiating hearing aid technology using tiers might have some limitations. Is that the case?

Brian Taylor: Absolutely. It’s not the tiering per se that has limitations, but for a long time the tiering has been based on number of channels. I think there was a time when there were some clinically significant differences between, say, a 3-channel and 8-channel hearing aid. For example, there was a time when a clinician could do more frequency shaping to match prescriptive targets with a 6- or 8-channel device compared to a 2- or 3-channel device, and those devices with more channels would warrant a higher price tag. But those days are in the rear-view window.

AudiologyOnline: Why do you say those days are in the rear-view mirror?

Brian Taylor: Maybe it’s unfair to say those days are in the rear-view mirror when it’s still quite popular to differentiate technology tiers using number of channels. After all, using the number of channels across three or four hearing aid models (good, better, best) is an easy, intuitive way to position hearing aids. Plus, it’s a relatable way to discuss with prospective wearers their options at various price points. I think most of us would agree that consumers like choices and the good/better/best technology tiers is a useful way to position these choices. My beef is we shouldn’t be tiering technology based on the number of compression channels. It has significant limitations.

AudiologyOnline: If the tried and true good, better, best tiering of technology based on number of channels is popular, then why should we reconsider it?

Brian Taylor: There are a few reasons for rethinking how we position today’s prescription hearing aids. First, there is an oft-cited study from almost 30 years ago (Yund & Buckles, 1995) that compared word recognition scores from 4-, 8- and 16-channel hearing aids. Aided word recognition scores increased from 4 to 8 channels but did not change significantly between 8 and 16 channels. Assuming you are providing ample high frequency gain and a smooth, broadband response, this study tells us that 8 channels of compression is probably enough to maximize speech understanding. Now I know this is only one study and it was conducted on just 16 adults, but it’s a good reminder that a really large number of channels, like we find in today’s prescriptive hearing aids, probably doesn’t directly contribute to patient benefit. These days even basic technology often has 16 or more channels of compression. Let’s say a basic model has 16 channels and the premium model from the same manufacturer has 36 channels. Although I don’t know of any recent study that has evaluated differences based exclusively on the number of channels, it’s a safe bet that going from 16 to 36, or even 48 or 64 channels won’t result in significant improvements in wearer performance.

AudiologyOnline: Okay, maybe number of channels is not a good way to differentiate levels of technology. There must be other ways that manufacturers differentiate or tier their product lines.

Brian Taylor: Yes, thanks to the flexibility of digital microprocessors, certain features can be deactivated in lower levels of technology. It is common for basic technology to have less sophisticated noise reduction algorithms or perhaps to have an automatic steering with fewer destinations or programs. Every manufacturer deactivates certain advanced features in their basic devices. Today it is common to see both fewer channels and more deactivated advanced features in basic devices. However, there are other advanced features such as wireless streaming, and wearer-controlled apps that many wearers benefit from that are available across the entire product line.

AudiologyOnline: The fact remains that premium levels of technology result in greater levels of patient benefit compared to basic levels of technology. Do I have that right?

Brian Taylor: Intuitively, that makes sense, but unfortunately there is no evidence to support it. Let me address patient benefit and technology tiers first, and then if we have time, we can discuss some other elements of the patient experience and how they might relate to technology tiers. Remember benefit is the difference between performance in the unaided and aided condition on a listening task completed in the booth, so called laboratory measures, or a self-report metric of how the hearing aids work in everyday listening conditions of the wearer, commonly referred to as real-world measures.

AudiologyOnline: I know some of our readers may find that hard to believe. Could you elaborate?

Brian Taylor: I would be happy to. The first study, published in three parts (Cox, et al 2016; Johnson, et al 2016; Johnson, et al 2017), fitted 45 adults with medically uncomplicated hearing loss with 4 pairs of hearing aids (one premium, one basic from two manufacturers). Each pair of hearing aids were worn for one month and all study participants were blinded to the level of technology they were wearing. Researchers conducted several lab and real-world outcome measures (speech understanding, listening effort, etc.) at the end of each one-month trial. All in all, results showed no meaningful difference in patient outcomes between premium and basic technology levels.

A similar study comparing premium and basic was conducted by Wu, et al (2019). In this study they compared premium and basic on 54 adult wearers in which each pair of hearing aids (one basic, one premium) were worn for five weeks. The researchers measured items such as speech understanding, listening effort, sound quality, localization, and satisfaction. For the lab measures, premium tended to outperform basic. However, in everyday listening conditions, there was no difference in outcomes between the two technology tiers.

There are two other recent studies that warrant a mention. Both had outcomes similar to the first two studies I mentioned. One comes from Western University in Canada. Saleh, et al (2022) collected lab and real-world outcome data on 23 adult hearing aid wearers that compared basic and premium technology using an approach like the two studies described above. Their analysis showed no difference in lab or real-world outcomes between these two technology tiers. (More on this study later.) Finally, using a different approach in which they retrospectively reviewed self-reports of outcome on a 32-item questionnaire of 1149 wearers, Lansbergen, et al (2023), found wearers of devices with more basic features had essentially the same average scores on the 32-item self-report as those wearing hearing aids classified as having more premium features.

AudiologyOnline: That’s a little surprising. What do you think explains these findings?

Brian Taylor: I believe there are a couple of things driving these findings. First, these findings speak to the quality of all prescription hearing aids on the market today. All modern prescription hearing aids, regardless of technology tier, do three things well when placed in the hands of the clinician. One, they optimize audibility when frequency shaping is done to match targets for soft, average and loud input levels. Two, they accommodate the wearer’s dynamic range when the MPO is kept just below the wearer’s loudness discomfort level (LDL), and three, they implement a combination of spatially based (directional microphone systems) and process-based noise management strategies. These three characteristics are nearly universal in prescription hearing aids, regardless of manufacturer and technology tier. And we cannot disregard the value of personalized counseling and orientation. In all four of the studies cited above, the audiologist took the time to carefully orient and counsel the patient, regardless of the technology level they used.

AudiologyOnline: Are there other reasons we don’t see a difference in wearer benefit in these studies that compare basic to premium technology levels?

Brian Taylor: Another reason might have something to do with digital technology. As everyone knows, each manufacturer uses the same digital processing circuitry, commonly known as a platform or chip across their entire product line. They simply deactivate certain features in lower levels of technology. Perhaps the underlying digital processing (sampling rate, delay, etc.), which is the same across the product line, contributes to these similar outcomes between premium and basic.

Finally, it is quite possible in all these studies many of the participants didn’t spend enough time in listening situations where premium hearing aids might outperform basic. In one of the studies cited above (Wu, et al 2019) they noted that participants spent about 90% of their time in quiet; thus, the benefits of premium hearing aids might not be fully experienced. Since the participants in that study were in demanding listening situations roughly 10% of the time, it is possible that they didn’t benefit more from premium because they didn’t spend enough time in the places where premium might outperform basic technology. Across the board, manufacturers tend to devote the most R&D resources to creating algorithms that optimize audibility in noisy places, and the most sophisticated versions of these algorithms are found in their premium devices. It makes sense that if the wearer spends 90% or more of their time in quiet, they may not be fully utilizing all the complexity of these algorithms.

AudiologyOnline: If I understand you correctly, there really isn’t a difference between premium and basic in real-world listening conditions. Maybe we should abandon the whole good, better, best approach?

Brian Taylor: I wouldn’t go that far. When you consider all the devices in these studies were meticulously fitted using best-practice principles and that most of the participants spent almost all their listening time in quiet places, we shouldn’t be surprised by these findings.

Plus, there were some important differences between basic and premium that wasn’t found in the lab and real-world benefit measures. It’s important to point out, for example, in both the Memphis University and Western University (Saleh ,et al 2022) studies, there was a strong wearer preference for premium.

AudiologyOnline: What do you mean by wearer preference? And what did those studies find?

Brian Taylor: Wearer preference is asking, using an A/B comparison, which pair of devices did you like? Or if given a choice between A and B, which one would you purchase? In the University of Memphis study, 93% of participants reported a preferred device, with 54% stating a strong preference for premium. In the Western University study, 83% of participants preferred premium technology, with just over half of that group reporting a “strong preference” for premium.

AudiologyOnline: Why was there such a clear preference for premium in those studies?

Brian Taylor: I don’t know if I fully know the answer. Fortunately, we have a few studies that can guide us. The first I’ll mention is that same Western University study in which 52% of the participants had a strong preference for premium. They used something called concept mapping to tease out what might be driving a preference for premium over basic technology. In their study they were able to sort preferences into nine unique clusters: 1.) sound quality and intelligibility, 2.) comfort and appearance, 3.) ease of use, 4.) complex factors, 5.) streaming, 6.) convenience and connectivity, 7.) acoustic feedback, 8.) user control via a smartphone app and 9.) multi-environment functionality.

Clusters 1, 2, and 3 were the highest rated for both groups. I take that to mean that all hearing aid wearers, regardless of technology think these attributes are important. The clusters that rated highest for the group preferring premium were streaming (5), convenience and connectivity such as accessory compatibility (6), and having access to a smartphone app for user control (8), These findings suggest to me that patients who have a strong need for (or believe they are important)) attributes (5), (6) or (8), might be good candidates for premium devices.

AudiologyOnline: But as you mentioned, aren’t many of these features – streaming, user-controlled apps, etc – found in pretty much all technology levels?

Brian Taylor: Yes, that’s true, so maybe we only activate and instruct patients how to use those features once we know they want them or really need them. Maybe in addition to tiering technology levels, we can also tier service levels. Let me explain by providing two suggestions based on how I would apply these research findings clinically:

- Recently, audiologists at Western University developed a questionnaire called the Hearing Aid Attribute Feature and Importance Evaluation (HAFIE) questionnaire (Saleh, et al 2023). They also developed a 14-item shortened version of the HAFIE that seems to be a good clinical tool to determine how important streaming, smartphone-based technology, and connectivity might be for the individual. Each response to the 14-items is on a 1-5 Likert scale. I believe they are still researching it, but the short version of the HAFIE is available. If a patient marked on the HAFIE that any of those items (streaming, connectivity & convenience or smart-based technology) as “very” or “extremely” important, in my judgement they would be excellent candidates for devices in which those features are activated. That is, whatever technology level we recommend, we want to make sure that the features are activated, and that the wearer is well versed on how to use them from the get-go. This leads directly to my second point.

- Granted you can get those features in any technology level, so this second step is important. Next, I would assess each person’s digital literacy using the two questions that come from the Mobile Device Proficiency Questionnaire (Roque & Boot, 2018). A modification of that questionnaire was created by Sucher et al (2023) in Melanie Ferguson’s lab in Australia. The two questions are:

- “How would you rate your skill level with a smartphone?”

Possible answers: never used, beginner, competent

- “How confident are you using a smartphone?”

Possible answers: not confident at all, usually need help, depends on task, confident

I believe they are continuing to study this approach, but here is how I would use it clinically: First, I would determine if smartphone-based apps and streaming features are important to the wearer. I would use the HAFIE to help determine this. If the HAFIE shows that these features are not important to the patient, I would deactivate them, perhaps in devices at a lower price point.

Second, if the HAFIE shows that these higher tech features are “very” or “extremely” important to the patient, I would administer those digital literacy questions. If the patient provides a response other than “competent” for Question A and “confident” for Question B, I would recommend hearing aids that have these features (streaming and wearer-controlled smartphone apps) activated, plus provide additional personalized instruction on how to use them. Of course, because you (or an audiology assistant) are going to be spending more time instructing this wearer, the latter recommendation would be at a higher price point. Consequently, wearers who deem these higher tech features to be very important, but need more personalized counseling would require a premium level of service.

AudiologyOnline: I recall Patrick Plyler at the University of Tennessee doing a 20Q last year for us on this topic. In that 20Q he mentioned some research his lab has done on wearer preferences for various technology tiers. How does that fit into what you are saying?

Brian Taylor: I am so glad you mentioned his AO article. It’s an excellent overview of the topic and I have already highlighted many of his key points. Readers can find that article here. I think he and his team were curious about the fact that outcomes between premium and basic were indistinguishable, yet there was this fairly strong preference for premium in some of those earlier studies we already discussed. These discrepancies between outcomes and preferences motivated them to conduct a study that tried to better understand what might be driving these differences.

In two different studies, one involving experienced (Plyler et al 2021) and the other new hearing aid wearers (Hausladen et al 2022), they examined the effects of technology levels on outcomes. Like the other studies measuring several dimensions of outcome, there was an indistinguishable difference between basic and premium, however, they did find some areas where premium did better than basic.

AudiologyOnline: What were those areas?

Brian Taylor: Well, you know the University of Tennessee is the home of the Acceptable Noise Level (ANL) test, so it’s not surprising that they used that test in these studies. They did find that wearers who preferred premium showed significantly more improvement on the aided ANL test. Presumably, premium technology because of it more sophisticated noise reduction algorithms improves some individual’s acceptance of background noise. They also found that satisfaction ratings for speech in large groups was significantly improved with premium technology. Another key finding was that wearers in more demanding listening areas preferred premium over basic.

AudiologyOnline: It’s sounds like we have findings from a couple of different studies that might guide our thinking in the clinic on who might be good candidates for premium technology. Do I have that right?

Brian Taylor: Yes. It’s safe to say that we cannot make blanket statements such as, “All patients will experience better outcomes from premium compared to basic technology. However, I do think we can use these studies to take a more nuanced approach on how we recommend hearing aids. And we can do this without completely abandoning the consumer-friendly tiering approach.

AudiologyOnline: Please share with us how you would apply the research on this topic in the clinic during the hearing aid selection process.

Brian Taylor: First, this line of research comparing premium to basic technology tells us that properly fitted hearing aids trump hearing aid technology level. It’s a good reminder that when best practice principles are followed (like in all these studies), outcomes tend to be favorable, regardless of technology level. That is a message we should share with persons with hearing loss who have chosen not to acquire hearing aids. Further, it is a message to share with other medical professionals such as physicians and nurse practitioners who come into frequent contact with individuals who need hearing aids but do not wear them.

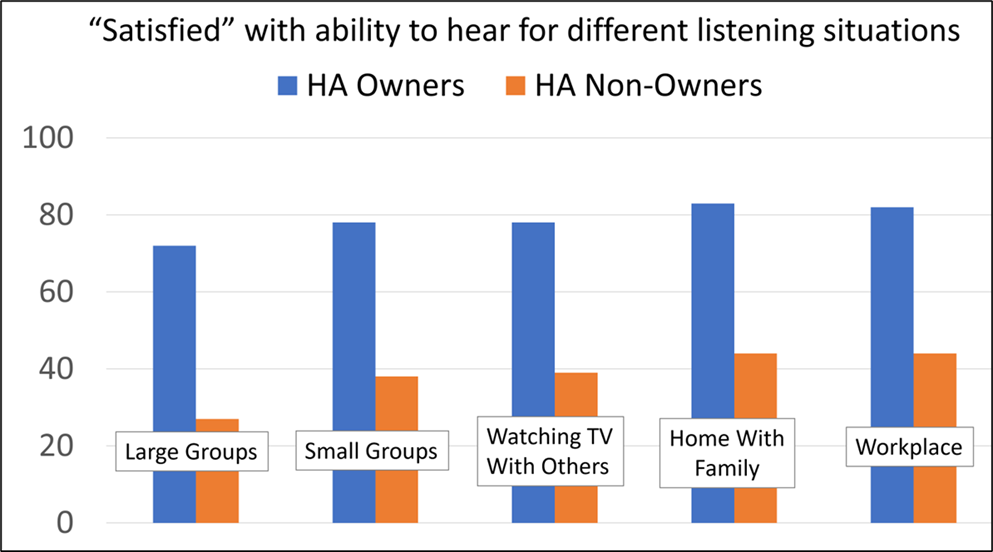

We haven’t yet mentioned much about satisfaction, but we know it is an important dimension of outcome. For example, look at the data in Figure 1. It compares wearer satisfaction for common listening situations, between hearing aid owners, and individuals with hearing loss who are non-owners. This is MarketTrak 2022 data from 1,061 hearing aid owners (presumably wearing a wide variety of technology levels), and 1,840 hard of hearing non-owners. Note the large differences in hearing satisfaction for all categories—a difference of 40% or more in most cases. Importantly, also note that satisfaction for the hearing aid owners is around 80% for situations which are commonly thought of as “difficult.” This is at, or near, the satisfaction rate for individuals with normal hearing. Finally, hearing aid wearer satisfaction has steadily climbed over the years from a low of 58% in the early 1990s to higher than 80% today. This speaks, at least in part, to the incremental sound quality and signal processing improvements in all prescription hearing aids.

Figure 1. Satisfaction (percent of respondents) with ability to hear in different listening situations for owners of hearing aids vs. individuals with admitted hearing loss who do not own hearing aids. From Picou, 2022. Figure created by Gus Mueller.

I almost forgot to mention one last point on this matter…..I’ll give you another reason why it’s important to share the data in Figure 1 with patients and referral sources. Public policy and healthcare experts outside our profession, when they are advocating for low-cost OTC and DTC hearing solutions, tend to focus on the high average price of a pair of prescription hearing aids. What they often fail to mention is that basic hearing aids, available at a much lower price than the average pair of hearing aids, provide outstanding benefit and satisfaction. In my experience, it is still possible to purchase a pair of hearing aids with basic technology that include professional service at a price point comparable to many OTC hearing aids. The fact that you can purchase a pair of “basic” prescription hearing aids with professional service at a price point comparable to a pair of OTC devices, and not sacrifice quality of outcomes, bodes well for persons with hearing aids who have not yet committed to acquiring hearing aids.

AudiologyOnline: Ok, that seems like a reasonable message. You mentioned there are other ways this premium vs. basic research can be applied clinically. I’m guessing from the title of our interview, the term “new generation” features are involved?

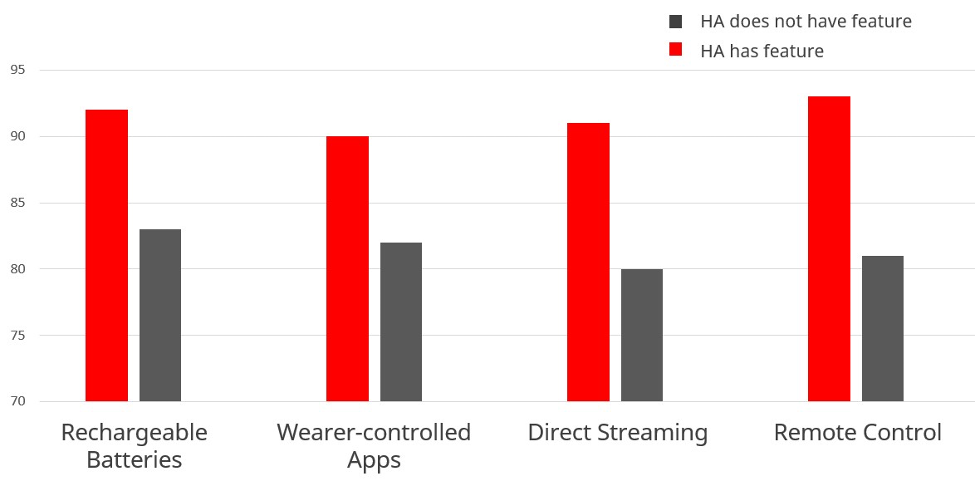

Brian Taylor: Yes, that’s true but first allow me to add that one conclusion from the studies we’ve been discussing today is that many patients have a clear preference for one hearing aid over another. In many cases they prefer premium, and according to one study (Saleh et al 2022), this preference for premium is driven, at least in part, by the desire to use higher tech features such as direct streaming, use of wearer-controlled apps and other accessories. This finding also aligns with some MarkeTrak 2022 data (see Figure 2) which suggest that wearers who have these higher tech levels tend to report higher levels of satisfaction. At Signia, we use the term “new generation” features because many of these features, while available across all technology tiers, were not widely available in hearing aids until around 2017, as we discuss in this recent article.

One way to leverage these findings is to measure and prioritize these wearer preferences. A tactic I would use in the clinic, one that I already touched on, is a more careful and deliberate assessment of who needs, or who would benefit from, “new generation” hearing aid features. Of course, these features are found across all technology tiers, but in my experience, providers tend to gloss over them or activate them in a random way. Therefore, I would encourage providers to use a self-report like the short version of the HAFIE to assist their patients in prioritizing use of these features. Then, I would assess their digital literacy with those two questions, as I mentioned earlier. Results from those two steps, inform you in a more precise way who needs those “new generation” features activated and who needs additional instruction using them.

Figure 2. Hearing aid satisfaction (percentage of respondents) of four new generation features for wearers that reported they had each feature compared to those reporting they did have the feature. Adapted from Picou, 2022.

AudiologyOnline: Interesting, since wearer-controlled apps, direct streaming and rechargeable batteries are found in all technology levels, that term, “new generation,” seems like a good one. How does that tie into moving away from the number of channels used in the good/better/best tiering process?

Brian Taylor: A fresh approach to tiering – one that voids the number of channels -- might look like Table 1. It shows that when these “new generation” features are activated and more professional service is used to ensure these features are optimized by the wearer, the higher the price point. It suggests that we can tier service just like we tier technology.

Best: Apps and direct streaming features activated; wearer receives personalized instruction. $$$ |

Better: Apps and direct streaming features activated; wearer doesn’t need instruction. $$ |

Good: Apps and direct streaming features deactivated. $ |

Table 1. Tiering approach that combines wearer preferences and digital literacy of new generation features.

Another way to leverage the findings of this line of research, particularly the work from Dr. Plyler’s lab, is to thoroughly assess the type of listening situation where it is important for the wearer to communicate. Recall the results of the studies in his lab suggests that listeners in more demanding environments preferred premium hearing aids over basic devices. A primary reason for this preference for premium is that the wearer could accept more background noise with premium in their demanding day-to-day listening situations. Thus, premium hearing aids may only be beneficial for wearers who find themselves in demanding listening situations.

AudiologyOnline: How can a clinician determine who is in a demanding listening situation?

Brian Taylor: That’s a tough question and I don’t have a good answer. I can, however, provide you with an opinion that might help in the clinic. Plyler’s lab used the hearing aid’s datalogging system to determine how often wearers were in challenging listening situations. As you know, most manufacturers use automatic steering programs that rely on signal classification systems to determine when various noise reduction features are activated. And their premium devices have more programs or destinations to be steered into by their classification system. Because each manufacturer applies different rules to determine when their automatic programs switch into a setting for noise, it makes this approach complicated if you’re dispensing devices from multiple manufacturers. Plus, using data logging to determine who is in demanding listening situations doesn’t make sense with new wearers unless you want to send them home with a pair of demo devices for a few weeks, and then evaluate their “datalog,” before they agree to acquire hearing aids.

Instead, I would encourage each clinician to create their own criteria for what constitutes a demanding listening situation. I would start with some data collected by WS Audiology principal scientist, Carolina Smeds. In 2015, her team used acoustic recordings collected by adult hearing aid wearers during their typical daily routines to estimate the signal to noise ratios (SNR) of their listening surroundings. They found that when the listening situation consisted of multiple talkers (like a restaurant or social gathering) the average SNR was +5 dB or worse. This tells me that any situation consisting of multiple talkers is likely to be a demanding situation in which the SNR is likely to be unfavorable.

Next, I would want to know how important it is for the patient to communicate in these demanding listening situations. Notice I am not asking how often the patient is in these situations, but how important it is to hear in places with multiple talkers. During the assessment you could ask, “On a scale of 1 to 10, with ten being the most important, how important is it for you to hear in restaurants or social gatherings?” If you get a score of say, 7 or higher, that might be an indication the clinician should recommend premium technology for that individual.

I want to be clear; this approach comes from how I would apply the research on this topic. But to paraphrase Raymond Carhart, “Unlike researchers, clinicians do not have the luxury to wait several months or years for other facts to appear….the decisions of the clinician are more daring than the decisions of the researcher because human needs that require attention today impel clinical decisions to be made more rapidly and with less evidence….the dedicated and conscientious clinician should bear this fact in mind proudly.” Consequently, we must act with the best available information we have today.

AudiologyOnline: Take us through the process of how you might recommend premium?

Brian Taylor: Using the principles I just mentioned, I would have an in-depth conversation and try to gain a better understanding of the “demandingness” of the individual’s listening environment and how important these situations are in their daily lives. I would record these goals on the individual’s COSI. If the individual is in demanding listening environments (i.e., social gatherings with multiple talkers) and they deemed to be important (7 or higher), I would not hesitate to recommend premium technology because it gives that person the best chance of being successful (accept more noise).

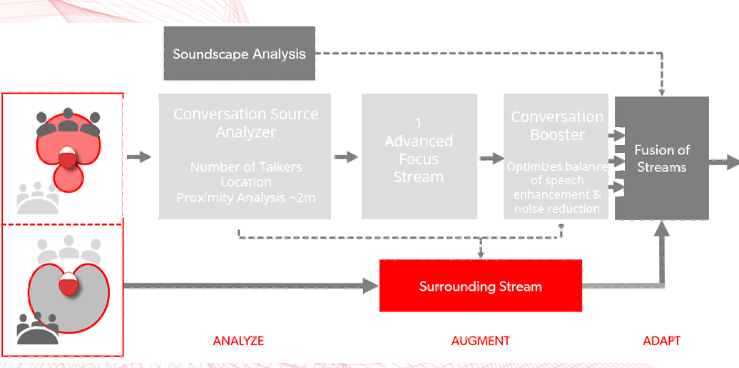

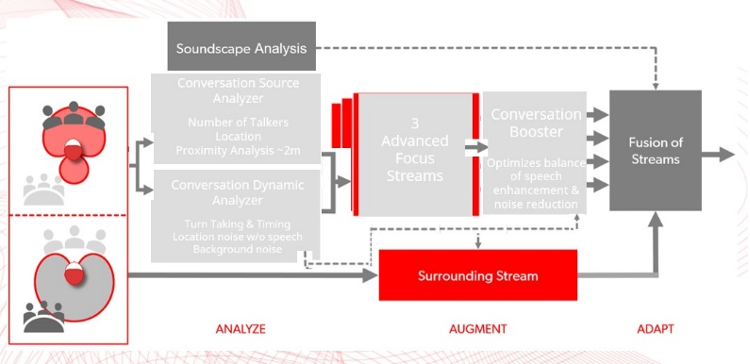

There is one additional point I would like to make here as it relates to Signia hearing aids. With the IX platform, we have designed a hearing aid to optimize conversation, particularly in groups. Because of how Signia implements wireless bilateral beamforming, IX can constantly scout the acoustic environment to identify number of talkers and their location and apply a proprietary algorithm, Real Time Conversation Enhancement (RCTE) to increase gain for speech. However, when you compare mid-level (5 IX) to premium (7IX) technology, as shown in Figure 3 and 4, notice there are more focus streams or what I call “acoustic snapshots” around the wearer that are independently scouting, identifying and increasing gain for speech – in each of the snapshots. Thus, the 7IX is ideally suited for any individual who values better hearing in group conversations – situations that I would classify as demanding. Couched in the language of the dispensing audiologist, who is tasked with making a firm recommendation, the premium (7IX) level provides the best bang for the buck for anyone who prizes improved communication in demanding, group conversations. Obviously, we must be cognizant of everyone’s budget, but the best way to optimize the chances of success in group conversations is by recommending 7IX for individuals who prioritize listening in demanding situations.

Figure 3. Signia 5 IX with one advanced focus stream

Figure 4. Signia 7IX with three advanced focus streams.

AudiologyOnline: This was an informative interview. Could you provide our readers with a summary of your key points?

Brian Taylor: Sure. One, take the time to better understand who really wants or needs wireless streaming, wearer-controlled smartphone-based apps and other “new generation” features. Having a better grasp of who these individuals are determines when to activate these features and recommend premium levels of service. Two, carefully determine who values communicating in demanding listening situations and don’t hesitate recommending Signia’s 7 IX premium technology, which is specifically designed to optimize communication in group conversation settings.

Finally, let me conclude by sharing with you a memorable approach to how we can shift away from tiering based on number of channels to tiering based on preference for “new generation” features and premium noise reduction/speech enhancement technology. I am old enough to remember a time before the internet existed. Back in the early 1990s, there was a tech magazine, called Wired, that had a monthly column they called Tired vs. Wired. It was a barometer for what was culturally passé (tired) and what was considered fresh and new (wired). Using their approach, I have included a third take.

Tired: Thinking more channels equates to improved wearer benefit.

Wired: Prospective wearers who have a preference for streaming and smartphone apps but have low digital literacy = recommend premium service. Prospective wearers who prioritize communicating in demanding listening situations = recommend premium technology.

Inspired: Signia 7IX, by virtue of its multiple acoustic snapshots and Real Time Conversation Enhancement, is the best choice for optimizing performance in demanding situations such as group conversations.

References

Cox, R. M., Johnson, J. A., & Xu, J. (2016). Impact of Hearing Aid Technology on Outcomes in Daily Life I: The Patients' Perspective. Ear and hearing, 37(4), e224–e237

Hausladen, J., Plyler, P. N., Clausen, B., Fincher, A., Norris, S., & Russell, T. (2022). Effect of hearing aid technology level on new hearing aid users. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 33(3), 149-157.

Johnson, J. A., Xu, J., & Cox, R. M. (2016). Impact of Hearing Aid Technology on Outcomes in Daily Life II: Speech Understanding and Listening Effort. Ear and hearing, 37(5), 529–540.

Johnson, J. A., Xu, J., & Cox, R. M. (2017). Impact of Hearing Aid Technology on Outcomes in Daily Life III: Localization. Ear and hearing, 38(6), 746–759.

Lansbergen, S., Versfeld, N., Dreschler, W. (2023) Exploring Factors That Contribute to the Success of Rehabilitation with Hearing Aids. Ear and Hearing P-A-P, June 09, 2023.

Picou, EM (2022) Hearing Aid Benefit and Satisfaction Results from the MarkeTrak 2022 Survey: Importance of Features and Hearing Care Professionals. Semin Hear 43:301–316

Plyler, P. N., Hausladen, J., Capps, M., & Cox, M. A. (2021). Effect of hearing aid technology level and individual characteristics on listener outcome measures. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 64(8), 3317-3329.

Roque, N. A., & Boot, W. R. (2018). A New Tool for Assessing Mobile Device Proficiency in Older Adults: The Mobile Device Proficiency Questionnaire. Journal of Applied Gerontology: the official journal of the Southern Gerontological Society, 37(2), 131–156.

Saleh, H. K., Folkeard, P., Van Eeckhoutte, M., & Scollie, S. (2022). Premium versus entry-level hearing aids: using group concept mapping to investigate the drivers of preference. International journal of audiology, 61(12), 1003–1017.

Saleh, H. K., Folkeard, P., Van Eeckhoutte, M., & Scollie, S. (2022). Premium versus entry-level hearing aids: using group concept mapping to investigate the drivers of preference. International journal of audiology, 61(12), 1003–1017.

Smeds, K., Wolters, F., & Rung, M. (2015). Estimation of signal-to-noise ratios in realistic sound scenarios. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 26, 183-196.

Sucher, C, Sahoto, T & Ferguson, M. (2023). Don’t assume I’m too old: Why we should assess the digital literacy of adults with hearing loss. Student thesis Ear Science Institute

Wu, Y. H., Stangl, E., Chipara, O., Hasan, S. S., DeVries, S., & Oleson, J. (2019). Efficacy and Effectiveness of Advanced Hearing Aid Directional and Noise Reduction Technologies for Older Adults With Mild to Moderate Hearing Loss. Ear and hearing, 40(4), 805–822

Yund, E. W., & Buckles, K. M. (1995). Multichannel compression hearing aids: effect of number of channels on speech discrimination in noise. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 97(2), 1206–1223.

Brian Taylor, AuD is the senior director of audiology for Signia. He can be contacted at brian.taylor@wsa.com