From the Desk of Gus Mueller

From the Desk of Gus Mueller

A Happy 2023 greetings to you all! We’re diving into our 13th year of the 20Q column here at AudiologyOnline! If you go back to when the column resided at The Hearing Journal, it’s the 30th year, but who’s counting? We are going to start the year off with a Q and A that is a little different from our usual topics. It’s about the art, not specifically the science, of clinical audiology. But first, a quick background story.

It was the fall of 1971. I had just finished my master’s degree, and with very minimal clinical experience, jumped into a caseload of 15 or more diagnostics/day at an Army Medical Center. In an attempt to stay one step ahead of my next-day’s patients, I immediately purchased the newly published Katz Handbook of Clinical Audiology. Each night I would read and outline one or two of the 41 chapters. When desperate, even read about Bekesy audiometry test interpretation while the patient was taking the Bekesy test (14 minutes to run pulsed and continuous).

There were (and still are) many great chapters in that book, but the one that I’ve always remembered the most fondly was written by psychologist David Green on pure tone air conduction thresholds. Much of the chapter related to the “art” of this clinical measure, and my favorite section was the five pages devoted to UFOs (Useful Finger Observations), where Dr. Green cleverly described the six patient-response finger movements that we all should be familiar with. This chapter also told me that it’s okay to have a bit of fun when writing about audiology.

Fast forward 50 years. I recently became aware of a book titled Guide to NHS Audiology Placements.

The title is somewhat misleading, as it’s really a guide for all new clinical audiologists, and maybe some old ones too, as it is packed full of useful clinical tips, much like the UFOs of Dr. Green. Good information that should be shared at 20Q, I thought. The author of the book is Barnaby Growling, and here is where it gets rather interesting. Like Mark Twain, Lemony Snicket and Dr. Seuss, Barnaby Growling is a pseudonym. Now, you might find it a bit odd that we are publishing a 20Q written by an unknown author, but hey, in 2006, The Hearing Journal published an article written by The KEMAR, who, last I checked, isn’t even a person!

Gus Mueller, PhD

Contributing Editor

Browse the complete collection of 20Q with Gus Mueller CEU articles at www.audiologyonline.com/20Q

20Q: Audiology - There’s an Art to this Science

Learning Outcomes

After reading this article, professionals will be able to:

- Define the difference between being informed and being knowledgeable.

- Explain what artful practice is and how it might vary across the world.

- Describe anosognosia.

1. I’ve always thought that art and science were taught separately?

Indeed, and supposedly, never the twain shall meet! I used to think the same way before I began training in a real audiology clinic. After listening to the opinions of small independent business owners, clinical directors, and transnational CEOs, I’m now more convinced than ever that the employment prospects of any audiologist, established or aspiring, will be served well by nurturing the development of artful practices.

My impression is that private sector employers, at least those involved with hearing aids, are more likely to consider a candidate conducive to a thriving business if the candidate can demonstrate the ability to adapt. They should be able to adapt their authority over evidence-based methods and to flatter the idiosyncrasies of as many members of the population as possible. The ideal objective is to empower all suitable hearing aid candidates to accept and achieve success with this potentially life-changing treatment recommendation.

2. Why do you think artful practices are so valuable to employers?

I was once interviewed for a position by the Director of Audiology, Joanna Magee, whose father is one of the founding members of the Australian College of Audiology. Joanna had 30 years of clinical experience and firmly took the reigns of the family business in Northern Queensland. This business had stood for three generations by the time we met. Joanna informed me that every year she would adopt one college student from the latest state cohort and shepherd them through to the completion of their mandatory clinical internships. The thing I remember most starkly from our interview was when Joanna explained that she employed audiologists for their art and not for their science. She deduced that each of the new audiology graduates she encountered during her college career visits were clones. By this she meant that they had all fulfilled the requirements for a Master of Science degree. They had learned those skills such as how to verify hearing aids optimally using real-ear measurement (REM) (British Academy of Audiology & British Society of Audiology, 2019), how to conventionally interpret a tympanogram according to type (Jerger, 1970), how the COSI should be tackled (Dillon et al., 1997), what the retro-cochlear significance of unilateral tinnitus could be (Baguley, 2006), and which specialist to refer on to for further investigation (Yew, 2014).

However, only a handful from each cohort demonstrated art in their practice. Art refers to those soft skills that are harder to encapsulate within a marking scheme. Art includes skills like the ability to find time to make people feel listened to by speaking less, and by asking Socratic questions. Asking questions can unearth insight into real-world benefit (Taylor, 2022) and uncover the root cause of ‘hearing aid in the drawer syndrome’ (Kochkin, 2000). Art in practice also includes the ability to bring test results to life with intuitive analogies and practical demonstrations (Schumacher et al., 2019).

Other artful practices include respectfully navigating around perceived wisdom spouted as fact and diluting information to make it easy for patients to choose the most optimal treatment for them amidst a murky sea of choice (Sivanathan & Kakkar, 2017).

An audiologist is most likely to inspire compliance from a patient based on the strength of their relationships rather than on the strength of their arguments (Thiedke, 2007), no matter how many letters they have after their name.

3. This concept sounds abstract. How can we develop a concrete sense of art in our practice?

Craft is built from personal trial and error and a sense of history, i.e., learning from stories about the successes and failures of those who came before us. What audiologists around the world have access to in abundance, more so than ever before, is incredibly vast amounts of data and information (Marr, 2018). Nevertheless, the internet has also armed our patients with more information about hearing science than any audiologist I know could ever hope to hold in their brain.

Furthermore, with affordable over-the-counter hearing aids threatening the audiologist’s role in the future (Thompson, 2022), it begs the question: what will audiologists be valued for in years to come? What commodity will we possess that our patients could not acquire separately? The reason I think informed patients of the future will still have a reason to seek the consult of audiologists is to profit from our knowledge and counseling.

4. What’s the difference between being informed and being knowledgeable?

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines knowledge as “the fact or condition of knowing something with familiarity gained through experience” and “acquaintance with or understanding of a science, art, or technique” (Merriam-Webster, n.d.). Whereas information is defined differently as: ‘"facts provided or learned about something or someone" (Merriam-Webster, n.d.). In other words, while knowledge requires experience, it’s possible for a person to possess a wealth of information about a subject with which they have no personal experience.

5. Why is being knowledgeable more valuable than being informed?

Information is free and excessive in modern society; knowledge, by comparison, can only be gained through experience, which is a much rarer commodity. Ultimately, you have to have been there. Tech-savvy patients can already acquire hearing aid software and Noahlink wireless hardware to self-program hearing aids they elected to purchase online. With the emergence of autoREMfit (Mueller & Ricketts, 2018), who knows, they might well attempt probe-microphone measurements on themselves one of these days also.

What they don’t have is the working knowledge of an audiologist. This knowledge is gained from counseling thousands of individuals with varying auditory processing capabilities through the diverse psychophysical twists and turns of acclimatizing to hearing aids. Why does everything sound weird? Will these damage my hearing? Which prescription should I use? Can I wear this device part-time? What happens if I only wear one? Should the water in my kitchen sink sound like Niagara Falls? Is there an easier way of putting this in? Should the hearing aid whistle when I put my hand over my ear? How long will this take to get used to? What’s that static I can hear in the background? Why has my tinnitus changed since wearing these? Should my voice echo? Why is it that I still can’t hear my wife if the TV is on in the living room? It can be a long and lonely road figuring all this out for yourself without help.

6. I think I see what you’re getting at, but wouldn’t people just Google the answer to those questions too?

We can all Google and self-diagnose what ails us already. We can even purchase over-the-counter medications to treat a range of illnesses without prescriptions if we wish. Quite a few of us do (Hochberg et al., 2020). But, many of us still sit patiently in our doctor’s waiting room for the reassurance of their opinion, especially for more complex complaints.

Why? For me, it’s because I hope they will share one thing with me that I don’t have, which is knowledge gained from experience. I’m hoping that the doctor will put my mind at ease with a human acknowledgment of my symptoms. I hope he or she has ultimately seen what I am suffering from before and will have witnessed what it takes to treat the complaint successfully. In a future world where hearing aids, fitting software, and autoREMfit are readily accessible to all, I anticipate that it’s our experiences as audiologists that stand the greatest chance of preserving our worth. It is our experiences rather than our access to information, recommended procedures, and prescribed technology.

7. Hang on a second! Isn’t the whole point of developing standardized recommended procedures to ensure optimal outcomes for all patients, regardless of where they are and who they see?

In the words of Tachii Oni, the founder of Toyota: “Without standards, there can be no improvement.” Professional bodies such as the British Society of Audiology (BSA), American Academy of Audiology (AAA), and the American Speech–Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) offer a free archive of exhaustive resources that outline exactly how to perform almost every audiologic procedure. Each one has been peer-reviewed by a team of experts who have performed systematic reviews to ensure that the recommendations being made are supported by the strongest research evidence available (Mueller et al., 2021).

By adhering to these recommendations, you can be secure in saying that you are conducting yourself in a manner currently supported by the most robust evidence known to science. This is very difficult to argue with when challenged. It offers an invaluable source of power to audiologists taking their first steps as they perfect their craft. I’m a big fan, don’t get me wrong.

8. Then what is the downside? Where do artful practices come in?

The research included in the systematic reviews that led to the development of these recommended procedures relies on sample sizes that pale in comparison to the number of people who are estimated to have hearing loss in the world. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates this number to be in excess of 1.5 billion (WHO, 2022). Therefore, it’s not unreasonable to acknowledge that every single guidance document governing normative values, testing methodologies, anticipated test results, recommended hearing aid prescriptions, optimized hearing aid fittings, and instructional scripts should all be taken with a grain of salt rather than as indisputable gospel.

I consider recommended procedures to be an exceptional starting point for all clinicians. We are very fortunate to have them. Nevertheless, there are inherent limits in the generalizability of these documents for the billions of individuals out there. We need to remember why these documents are decisively named recommended procedures or guidelines rather than the audiology law book.

9. Recommended guidelines sound incredibly useful. I imagine every country where audiology is practiced must have its own. Right?

Wrong. In Australia, for instance, home of the world-renowned National Acoustic Laboratories (NAL), there are no recognized BSA, or AAA-equivalent recommended procedures. Students in each of the six Australian states learn their theory exclusively from their university, and this is how they practice. Once students graduate, however, the independent businesses that employ them have localized ways of working, and each state differs slightly in its approach. Every audiologist in Australia, and every other country without recommended procedures, must subsequently work much harder to avoid saying, that’s just how we have always done it around here during audits. It also makes it harder to defend against the pressures of adopting local practices, born of personal agenda and convenience, which may not necessarily be that well supported.

10. If students have recommended guidelines available, why do preceptors need to give them an appreciation of art in their practice?

It helps audiology students bridge the transition from academic learning to clinical know-how. After their initial academic indoctrinations are complete, and audiology students take their first steps into clinic, they are often in for a brow-furrowing shock. It happens when they attempt to apply their word perfect research-cultivated practices to unfiltered members of the general public. Making the selective need for artful adaptions transparent ahead of time may help students reconcile some of the stark contrasts between the purism of controlled laboratory role-play and the untidiness of real clinical interactions.

11. Can you give me an example of these differences?

Sure. I’m willing to bet that the audiology practitioners reading this article learned how to perform manual pure-tone audiometry using some variation of the modified Hughson-Westlake (1944) method (i.e., 5 dB up, 10 dB down, with two out of three correct responses on the ascent defining the threshold at each frequency). ASHA (2005) has produced research-supported guidelines that succinctly explain how the test environment should be organized, what equipment will be needed, and how to record results using symbols that are nationally recognized. The BSA (2018) guidelines go even further by offering a script for clinicians to use to instruct their patients:

I am going to test your hearing by measuring the quietest sounds that you can hear. As soon as you hear a sound (tone), press the button. Keep it pressed for as long as you hear the sound (tone), no matter which ear you hear it in. Release the button as soon as you no longer hear the sound (tone). Whatever the sound, and no matter how faint the sound, press the button as soon as you think you hear it, and release it as soon as you think it stops. (p. 8)

What these exhaustive recommended procedures all fail to mention, however, is how real patients inevitably misconstrue these instructions and what to do about that. I still marvel at how many ways I’ve seen patients misinterpret BSA-approved instructions, delivered verbatim, over the years. Here are some typical examples:

Mr. Lazy Thumb

Patients who like to rest their fingers or thumb on the response button are common. It often takes only the slightest decompression to elicit a response on your computer screen, unbeknownst to them. By resting his digits, Mr. Lazy Thumb will inadvertently make it seem like he is detecting a constant, never-ending sound. He will typically respond quite apologetically to a gentle reminder from the audiologist to press the button distinctly. Failing that, you can always ask him to utilize a different method of responding, such as raising a hand, tapping the desk, or nodding a head. The larger the movement a patient has to make in response to a test stimulus, the more reliable their responses are likely to be (Brennan et al., 2021).

Mr. Trigger Happy

Quite the opposite of Mr. Lazy Thumb, Mr. Trigger Happy presses the response button repeatedly, in rapid succession. He could be hearing his tinnitus, or it could be his imagination. Either way, he will press the button until the trumpets sound if he isn’t stopped. Conquering Mr. Trigger Happy may require one of many possible approaches. It may necessitate the use alternative stimuli like warble or pulsed tones, switching between ears at every octave. It may require repeatedly returning to familiarization level presentations to remind him what he is listening for, disciplined randomized stimulus presentations (having a ticking clock visible is often very helpful), and some persistent yet dispassionate sounding verbal re-instruction (Cooper & Lightfoot, 2000).

If you sound annoyed when you deliver your re-instruction, you might make the situation worse by making him nervous. Nerves could lead to Mr. Trigger Happy becoming reticent to respond to threshold-level stimuli for fear of making a mistake and annoying you more. Or, it may increase his rate of false positive presses to guarantee that he detects everything, audible or not. Either way, these lead to undesirable outcomes that are best avoided if possible.

Mr. Backwards

Mr. Backwards will always manage to interpret your instructions back to front. When you say, “please press the button every time you hear a beep,” he will press the button every time that he doesn’t hear the beep. When you say, “please make sure that you press even for the very quiet sounds,” he will only press the button for sounds that he considers audible. You will have to conduct several trial runs so that he can get the hang of things before you record his thresholds for real. Re-instructing using different adjectives and idioms is sometimes helpful as opposed to simply repeating the same instructions that he misinterpreted the first three times. For instance, rather than repeating, “please press the button every time you hear a sound” you might try, “hit that buzzer as soon as you hear a noise.” Sometimes, colloquialisms are instinctively understood better than formal instructions.

Mr. Slow Hand

Mr. Slow Hand is not Eric Clapton, unfortunately. Mr. Slow Hand is usually reliable, but he takes an extraordinarily long time to press the response button after he has registered the presence of the stimulus. Unfortunately, there is usually nothing to do but modify your presentation tempo. Some patients’ auditory processing simply cannot speed up and must be accommodated to ensure accuracy. Patience, young Padawan.

Mr. Disconcerting

Mr. Disconcerting will want to fix his gaze upon you throughout the entire hearing test. This is possibly due to fear that as soon as he turns his back, you will either pounce or vanish. Due to an inbuilt sense of honor and a natural aversion to shame, the threat of being labeled a cheater will often be enough to encourage him to turn his chair and face the wall during the test. If Mr. Disconcerting is tested inside a sound booth and chooses to stare straight at you through the booth window, you will likely need to utilize a makeshift hand shield. Typically, an open ring binder standing on its end will suffice.

Mr. Weeping Angel

Any audiology patient can become a weeping angel at any time. Born of a desire to catch every word you say, they will sneakily inch closer and closer to you during appointments. The minute you turn to look at your computer screen, whoa! There they are in your personal space. Weeping Angels can be fought off with a combination of constant vigilance and by ensuring that your patient chairs do not have wheels. Whatever you do, don’t blink!

12. How widespread are these eccentric behaviors?

I’m fairly certain that most audiologists and clinical scientists could come up with their own satirically informative caricatures for almost every procedural milestone that they shepherd their patients past every day.

We can also extend these caricatures to rehabilitation-oriented procedures.

Mr. Fidget

As soon as Mr. Fidget is instructed to remain as still as possible during real-ear measurements (REM), he will almost instantly start playing with wires, scratching his nose, looking out of the clinic window, and checking his watch. In other words, anything that defies the definition of sitting still. Not unlike a child, Mr. Fidget can’t stop himself from saying, “Hey, what language is she speaking?” in response to hearing the International Speech Test Signal (ISTS) for the first time. He will require regular polite reminders to remain stationary while he waits. If you happen to have a second computer monitor handy in your clinic room, at a zero degree azimuth, Mr. Fidget can sometimes be captivated by duplicating your screen and giving him some active wiggly lines to keep track of.

Mr. Boiling Frog

The story of the boiling frog is a grisly fable. The premise is that if you place a frog in a pot of water and then gradually heat the water to a boiling point, the frog won’t notice the temperature change and will succumb to said boiling. However, if you were to take a frog and place it in a pot of water with a pre-established rolling boil, it would jump out immediately to evade the danger. The moral of the story is that people are generally unwilling or unable to react to sinister threats that arise gradually. There is a certain breed of audiology patients who are not unlike our fabled frog. This is most noticeable when you fit hearing aids. During REM, the patient will have been played a verification speech stimulus many times at various volumes, which enables a degree of habituation toward amplification to occur.

Subsequently, when you seek some subjective validation with the question, “How does everything sound?” they will look at you blankly and say, “Is it switched on, it all sounds the same as it did before?” For these patients, it’s often necessary to turn off their hearing aids mid-way through a sentence and then back on again. Turning the hearing aids off and then on may make the hearing aid benefit more noticeable.

13. Aren’t narrative observations like these the weakest form of scientific evidence?

Sharing typical patient scenarios, as well as your experience in how to manage them, is very important. It’s true that anybody who has been near a critical skills appraisal program knows that case histories and anecdotes are right at the bottom of the evidence pyramid when it comes to testing scientific hypotheses (Murad et al., 2016).

On the other hand, we also know that narrative medicine is an engaging and effective tool for teaching concepts to students (Milota et al., 2019). Furthermore, there is research on feedforward teaching styles like storytelling, which focus on expanding a student’s idea of what’s possible rather than advocating strict adherence to protocol (Molloy, 2010). Feedforward refers to focusing on the future (as opposed to feedback, which focuses on the past). These teaching styles are known to help students integrate the insights gained during university simulations into their real professional practice (Morley et al., 2019).

14. Why do you think there is a lack of narrative-based audiology textbooks?

I’m not certain. The beauty is that any experienced audiologist could potentially write one. An awareness of the dissonance that exists between real-world clinical constraints, and recommendations stemming from the results of controlled experiments, have been felt since the age of Dr. Raymond Carhart (1975), who once proclaimed:

The clinician proceeds to gather as much data about his client as he can in a clinically reasonable time. He does not have the luxury to wait several months or years for other facts to appear. The decisions of the clinician are more daring than the decisions of the researcher because human needs that require attention today impel clinical decisions to be made more rapidly and on the basis of less evidence than do research decisions. The dedicated and conscientious clinician should bear this fact in mind proudly. He is the greater courage. (p. xxvii)

Select audiologists were flirting with the edges of this topic for years before I started pontificating about it. I’m reminded of a series of publications called myth-busters. Montano et al. (2017) wrote the first one that purposefully debunked the common procedure of explaining the details of the audiogram. This is something all audiology students are instructed how to do, which the authors argue acts against the patient-centered approach that they are shooting for. Patients frequently listen with little understanding of the jargon and symbols that have been discussed. Explaining the audiogram in this way reduces the time for having relatable discussions with the patient and answering questions (English, 2016). Sometimes it would seem sticking rigidly to recommended practices can act against the desires of the individual.

15. That sounds dramatic. Can you give me an example?

It has long been established (Zwislocki, 1953) that one way of treating the occlusion effect is to lengthen the meatus of a patient’s earmold (Killion, 1988) or custom hearing aid (Mueller, 1994) so that it extends to reach the medial bony portion of their ear canal. This prevents the cartilaginous portion of the canal from vibrating during vocalizations (Dillon, 2012), which in turn dampens the occlusion effect. Nevertheless, I have never managed to talk any of my patients into tolerating such a mold, microflex, or otherwise. They all report them to be too uncomfortable, and outright refuse to wear them. I was right to recommend it, but I was wrong to persist. Being right meant that these individuals stopped wearing their hearing aids.

We can explain much more to adults than we can to small children, even when our scientifically supported recommendations act directly against their wishes. Should we therefore assume that just because we can explain ourselves to them, that they will then follow our advice? I’m not so sure about that one. Students would do well to mentally prepare themselves for the dissonance that can occur when they recommend something strongly supported by the literature and a brave patient speaks up with negative feedback.

16. Speaking of children. Do artful practices apply to pediatric audiology also?

There are many publications in pediatric audiology that acknowledge that modifications to standard protocol are frequently required when carrying out behavioral assessments (Peck, 2020). Pediatric audiologists will often have to adopt a pragmatic child-friendly compromise to obtain the results required to guide management decisions with maximum efficiency.

Let’s take bone conduction (BC) testing, for example. To meaningfully establish whether a patient has a hearing loss or not, with a bone conductor, you must replicate the exact test conditions that were used to internationally standardize our chosen definition of normal hearing in the first place. In the case of the ubiquitous Radioear B71 bone-conduction oscillator, that would entail religiously utilizing the stock metal headband that the transducer comes attached to. However, as those acquainted with the Radioear B71 will attest, it’s not designed for comfort. So good luck getting your patients under 5 years of age to wear one.

Measuring BC thresholds is vital in a population so prone to conductive hearing losses, so we’re left to compromise when testing BC in children. We must adapt the standards to honor the circumstances. Usually, that means employing Mom or Dad to hold the conductor against the child’s mastoid. The dogmatic amongst you will know that one voltage can produce many different BC thresholds from the same patient, depending on how hard the vibrator is pressed into the mastoid. This may seem to make a mockery of the meaningful results that standardization is aiming for.

Nevertheless, when combined with OAEs, immittance findings, sound field testing, and/or ear specific air conduction (AC) testing, using an artistic license with an uncomfortable bone vibrator can get us within tolerance of our objective. Often that objective is to determine whether the child in front of us has AC thresholds worse than their BC thresholds, so that early intervention can be recommended without avoidable delay. How much bigger than 15 dB these air-bone gaps happen to be, is not vital for determining a definite need for medical intervention (Sabo, 1999). In other words, identifying the absolute position of the child’s bone conduction threshold, defined under conditions exactly relative to the standard, is not absolutely essential in this particular scenario.

17. You make it sound like audiology practiced outside of a laboratory is doomed to impurity. How do we defend against it?

Ironically, our savior might just be the standardization of our flaws and the open acknowledgment of our oversights. For example, there is credibility in the argument that none of us can accurately record high-frequency BC thresholds at present. False air-bone gaps occurring at 4 kHz in normal hearing listeners and those with sensorineural hearing loss is a well-published phenomenon (Margolis et al., 2013). This paradoxical event is linked to an international standards oversight made many years ago (Margolis et al., 2018).

Many of the things we measure in audiology are relative. As long we know that our frame of reference is flawed, we can still use these measures for certain applications, such as capturing deteriorations in sensitivity over time and establishing threshold asymmetries. This is analogous to somebody using a watch that is set to the wrong time zone, which is still ticking consistently, to accurately determine how many hours have passed since they last glanced at it.

18. What about clinical consensus? Is this a more practicable source of advice?

Recommended procedures and clinical consensus are no doubt synergistic and should therefore be utilized in tandem where possible. The reality, however, is that there are still many clinical phenomena that aren’t fully understood in audiology. Students are going to have to deal with ambiguity, regardless. Quite often, Delphi studies, peer review panels, a degree of educated speculation, and the opinion of an experienced senior colleague in the room next door will be all they have. Protocols guide us where available, but at the end of the day, audiologists are compelled to make decisions based on the patient in front of them being potentially better off. Even the prestigious Head of Research at the British Tinnitus Association (BTA), Dr. Magdalena Sereda, acknowledges that in the absence of evidence, we must instead look at clinical consensus and patient feedback to formulate our conclusions on how best to proceed (Sereda et al., 2015).

We live in an illogical world where the strongest predictor of long-term success with a hearing aid is not the severity of a patient’s hearing loss as captured on an audiogram. Instead, it’s a person’s self-perception of their hearing ability, which can be biased and completely irrational (Hickson et al., 2014). More unnerving still, a recent study in the US found that 43% of people who received testing that confirmed the presence of a pure-tone average hearing loss greater than 25 dB HL went on to report good hearing regardless (Curti et al., 2019). Tackling such displays of anosognosia with empiricism would be a mistake.

19. How can I tell whether one of my patients has anosognosia, and what can I do about it?

Anosognosia is a legitimate neurological symptom rather than a manifestation of denial or a coping strategy. It refers to the inability of a person to recognize a sensory disorder that they possess.

There are three tell-tale signs (Amador, 2022):

- The person’s lack of insight is severe and persistent, often lasting for months or years.

- The person’s beliefs about their condition doesn’t change, even when confronted with substantial evidence proving they are wrong.

- People with anosognosia will typically attempt to explain away evidence of the sensory deficit with illogical explanations and creative confabulations.

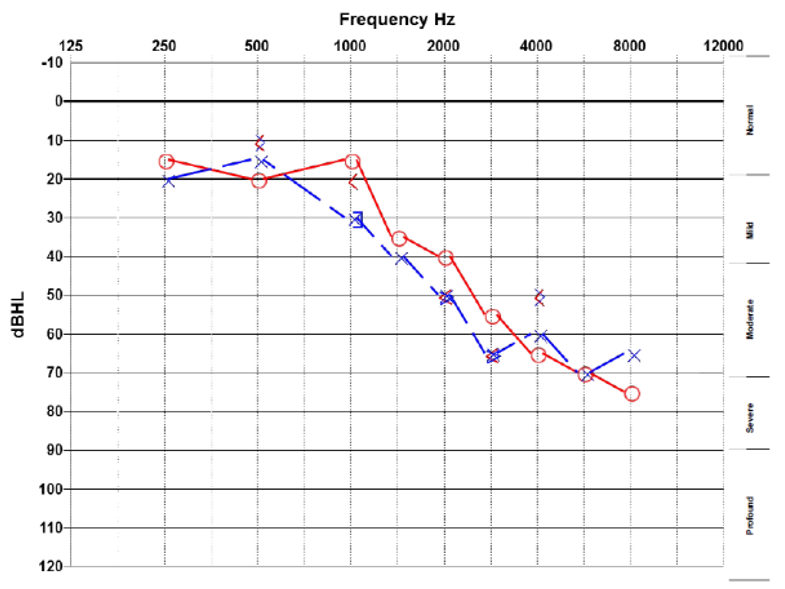

Let me give you two real-world examples. On the day that I conducted their diagnostic exams, I gave two different men with hearing loss a live hearing aid demonstration. My point was to show them what they’d both been missing due to their hearing losses (see audiograms in Figures 1 and 2). Despite both of them agreeing that they could hear noticeably clearer while aided, neither of them accepted the need for amplification. Instead, the retired carpenter (audiogram in Figure 1) concluded he knew what he thought they’d done, they’d moved the fridge, and whenever the power kicks back in, the fridge resets, and then the noise goes away until it’s left on again for a while. He stated that the TV was still on volume 18, as it always had been. This is an example of a belief not changing in the face of evidence and a creative confabulation about a fridge to boot.

Figure 1. Audiogram of a retired carpenter who had his hearing tested after his neighbor mentioned that his fridge was making a noise, which he was unaware of.

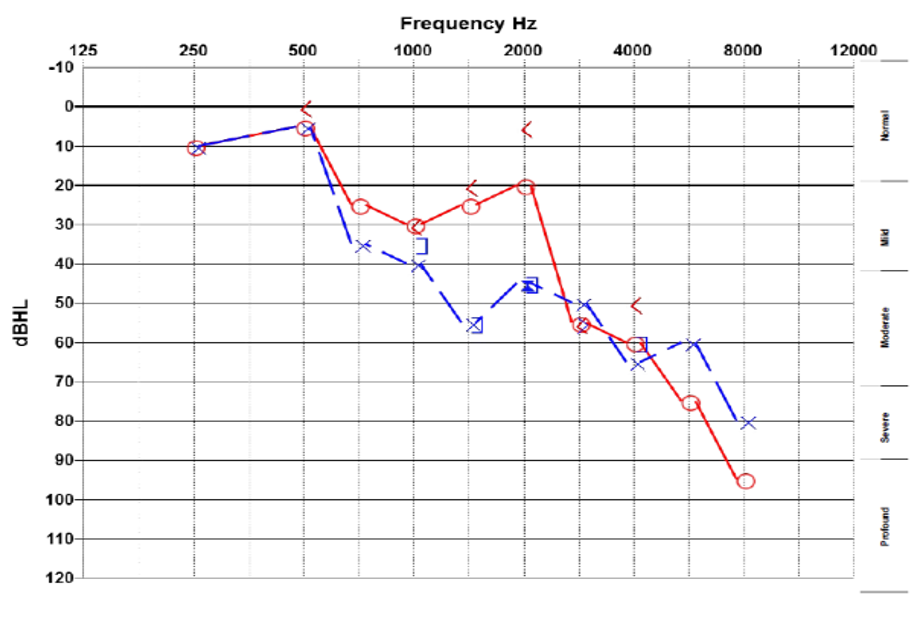

Figure 2. Audiogram of a retired concrete mixer who was burdened by new legislation requiring him to pass a hearing test to renew his commercial vehicle license.

The retired concrete mixer (audiogram in Figure 2) and his wife were both convincingly surprised by the unexpected news about his hearing loss. After some deliberation, he concluded that although he does have to think carefully about what people say sometimes, this is just what he’s like, and social situations are pretty noisy when you think about it. His wife supported this conclusion stating, she'll notice if his hearing gets bad; they've been married over 50 years.

Unfortunately, logic doesn’t work, but what you can do is aim for a détente (Nelson, 2013). Patients with anosognosia are understandably unwilling to admit they’re deluded, but that doesn’t mean you won’t convince them that acting to change is worth it. One thing clinicians must do is accept that educating these patients about their hearing loss will not usually translate into their gaining insight. A mistaken assumption is that patients with anosognosia have come to see you because they feel they have a problem and want help for the same reasons that you have for wanting to test them.

Clinical psychologist Xavier Amador (2012) offers the following advice:

Accept your powerlessness to convince. The first step is to listen in a way to leave them feeling their point of view is respected. You especially want to empathize with any feelings connected to delusions, which is not the same as agreeing that the belief is true. To avoid coming to an impasse, you need to look closer for common ground and for whatever motivation the other person might have to change. Once you know the areas where you can agree, you can now collaborate on accomplishing those goals. (p. 60)

This is not an easy or intuitive concept, but in cases of anosognosia, it’s possible to convince a patient to see the advantage in accepting hearing aids. Reasons such as having fewer arguments with their beloved spouse may motivate them to take action without convincing them they have a hearing problem. I think Harvey Dillon (2012) said it best:

The more a person is in contact with other people, or would like to be if poor hearing was not a disincentive, the more likely it is that the advantages of hearing aids will outweigh their disadvantages. A hermit with a loud TV set and radio does not need hearing aids!

Sometimes the only way to tackle anosognosia is for everyone to be submissive to the delusion. This may be rather unsatisfying, especially for the audiologist whose personal philosophy aligns strongly with positivism rather than pragmatism.

20. I think this motion passes. There does seem to be an art connected to this science of audiology. Do you have any closing remarks?

Art was historically a tool of education which relied on beautiful creations to gently encourage recalcitrant human minds to face the uncomfortable realities of life. Realities that said minds would be repelled by if confronted with in a direct business-like fashion (De Botton, 2019). Confronting some realities in a direct business-like fashion may backfire. Artistic practices have the power to raise ideas beyond the psychological shields that we employ. Imagine the pain of a bluntly delivered message denoting how the person in front us has lost their hearing. Hearing loss is tied so explicitly to the realization that life is an ephemeral possession. Such a direct message will probably encounter resistance and go nowhere.

Artful practices provide the means to gently meander down the river with our patients toward confronting these sobering realities. In conclusion, I implore all audiologists to remember the wise words of one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature, William Butler Yeats: “Think like a wise man, but communicate in the language of the people.”

References

Amador, X. (2022). Dr. Xavier Amador shares his experiences addressing anosognosia – Voices in Bioethics Podcast. Voices in Bioethics Columbia University Libraries. https://voicesinbioethics.podcasts.library.columbia.edu/dr-xavier-amador-shares-his-experiences-addressing-anosognosia/

Amador, X. F. (2012). I am not sick, I don’t need help! : how to help someone accept treatment (10th ed.). Vida Press.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2005). Guidelines for manual pure-tone threshold audiometry. https://doi.org/10.1044/policy.GL2005-00014

British Academy of Audiology & British Society of Audiology. (2019) Definition of optimally aided for experienced adult hearing users with severe to profound deafness. https://www.baaudiology.org/resources/

Baguley, D. M., Humphriss, R. L., Axon, P. R., & Moffat, D. A. (2006). The clinical characteristics of tinnitus in patients with vestibular schwannoma. Skull Base,16(2), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2005-926216

Brennan, S., Douglas, J., Doukas, T., Holtom, L., Martin, B., & McShea, L. (2021). Audiological assessment for adults with intellectual disabilities. British Society of Audiology. https://www.thebsa.org.uk/resources/

British Society of Audiology. (2018). Pure tone air conduction and bone conduction threshold audiometry with and without masking. British Society of Audiology. https://www.thebsa.org.uk/resources/

Carhart, R. (1975). Introduction. In M.P. Pollack (Ed.), Amplification for the hearing-impaired (pp. xxvii). Grune and Stratton.

Cooper, J., & Lightfoot, G. (2000). A modified pure tone audiometry technique for medico-legal assessment. British Journal of Audiology, 34(1), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.3109/03005364000000116

Curti, S. A., Taylor, E. N., Su, D., & Spankovich, C. (2019). Prevalence of and Characteristics Associated with Self-reported Good Hearing in a Population with Elevated Audiometric Thresholds. JAMA Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, 145(7), 626–633. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2019.1020

De Botton, A. (2019). The school of life: an emotional education. Penguin UK.

Dillon, H., James, A., & Ginis, J. (1997). Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) and its relationship to several other measures of benefit and satisfaction provided by hearing aids. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 8(1).

Dillon, H. (2012). Hearing aids. Boomerang Press.

English, K. (2006). Counseling Assumptions/Explaining The Audiogram | AdvancingAudCounseling.com. AdvancingAudCounselling. https://advancingaudcounseling.com/the-audiogram-to-explain-or-not-explain/

Meyer, C., Hickson, L., Lovelock, K., Lampert, M., & Khan, A. (2014). An investigation of factors that influence help-seeking for hearing impairment in older adults. International journal of audiology, 53(sup1), S3-S17.

Hochberg, I., Allon, R., & Yom-Tov, E. (2020). Assessment of the frequency of online searches for symptoms before diagnosis: Analysis of archival data. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(3). https://doi.org/10.2196/15065

Hughson, W. A. I. T. E. R., & Westlake, H. (1944). Manual for program outline for rehabilitation of aural casualties both military and civilian. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol, 48(Suppl), 1-15.

International Orgnaization for Standardization. (2016). ISO 389-3:2016(en), Acoustics — Reference zero for the calibration of audiometric equipment — Part 3: Reference equivalent threshold vibratory force levels for pure tones and bone vibrators. ISO. https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:389:-3:ed-2:v1:en

Jerger, J. (1970). Clinical Experience With Impedance Audiometry. Archives of Otolaryngology, 92(4), 311–324. https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.1970.04310040005002

Kochkin, S. (2000). MarkeTrak V “Why my hearing aids are in the drawer”. The consumers’ perspective. The Hearing Journal, 53(2), 34. https://doi.org/10.1097/00025572-200002000-00004

Margolis, R. Eikelboom, R., Moore, B., & Swanepoel, D. W. (2018). False 4-kHz Air-Bone Gaps: A Failure of Standards - The American Academy of Audiology. Audiology Today. https://www.audiology.org/news-and-publications/audiology-today/articles/false-4-khz-air-bone-gaps-a-failure-of-standards/

Margolis, R. H., Eikelboom, R. H., Johnson, C., Ginter, S. M., Swanepoel, D. W., & Moore, B. C. J. (2013). False air-bone gaps at 4 kHz in listeners with normal hearing and sensorineural hearing loss. International Journal of Audiology, 52(8), 526–532. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2013.792437

Marr, B. (2018). How Much Data Do We Create Every Day? The Mind-Blowing Stats Everyone Should Read. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2018/05/21/how-much-data-do-we-create-every-day-the-mind-blowing-stats-everyone-should-read/?sh=5de5bf4460ba

Milota, M. M., van Thiel, G. J., & van Delden, J. J. (2019). Narrative medicine as a medical education tool: a systematic review. Medical teacher, 41(7), 802-810.

Molloy, E. K. (2010). The feedforward mechanism: a way forward in clinical learning?. Medical Education, 44(12), 1157-1159.

Morley, D., Bettles, S., & Derham, C. (2019). The exploration of students’ learning gain following immersive simulation–The impact of feedback. Higher Education Pedagogies, 4(1), 368-384.

Mueller, H.G., & Ricketts, T.A. (2018). 20Q: Hearing aid verification - will autoREMfit move the sticks? AudiologyOnline, Article 23532. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com

Mueller, H.G., Coverstone, J., Galster, J., Jorgensen, L., & Picou, E. (2021). 20Q: The new hearing aid fitting standard - A roundtable discussion. AudiologyOnline, Article 27938 Available at www.audiologyonline.com

Mueller, H. G., Ricketts, T. A., & Bentler, R. (2017). Speech mapping and probe microphone measurements. Plural Publishing.

Murad, M. H., Asi, N., Alsawas, M., & Alahdab, F. (2016). New evidence pyramid. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine, 21(4), 125-127.

Nelson, E. (2013). Secret Identity. This American Life . https://www.thisamericanlife.org/506/secret-identity

Peck, J. (2020). Behavioral Techniques in Pediatric Audiology - The American Academy of Audiology. Audiology Today. https://www.audiology.org/news-and-publications/audiology-today/articles/behavioral-techniques-in-pediatric-audiology/

RadioEar. (2022). Bone Transducers - RadioEar. B71 Bone transducers. https://www.radioear.us/products/bone-transducers

Sabo, D. L. (1999). The audiologic assessment of the young pediatric patient: the clinic. Trends in Amplification, 4(2), 51-60.

Schumacher, J., Buemi, M. & Groth, J. (2019). The Power of the Demo: An Innovative Field Study Offers a New Perspective. AudiologyOnline, Article 25684. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com

Schupbach, J. (2017, February). 20Q: Clinical education and precepting - training the next generation of audiologists. AudiologyOnline, Article 19318. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com

Sereda, M., Hoare, D. J., Nicholson, R., Smith, S., & Hall, D. A. (2015). Consensus on hearing aid candidature and fitting for mild hearing loss, with and without tinnitus: Delphi review. Ear and Hearing, 36(4), 417–429. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000140

Sivanathan, N., & Kakkar, H. (2017). The unintended consequences of argument dilution in direct-to-consumer drug advertisements. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(11), 797–802. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0223-1

Taylor, B. (2022). The Relationship between Patient Satisfaction, Quality & Revenue: 8 Questions to Ask Yourself about Your Practice. Audiology Practices. https://www.audiologypractices.org/the-relationship-between-patient-satisfaction-quality-revenue-8-questions-to-ask-yourself-about-your-practice

Thiedke, C. C. (2007). What do we really know about patient satisfaction? Family Practice Management, 14(1). www.aafp.org/fpm.

Thompson, G. (2022) A cute baby dressed like a turtle and the evidence for OTC disruption. Audiology Practices. https://www.audiologypractices.org/audiologists-opinions-on-otc

World Health Organization. (2022). Hearing loss. WHO. https://www.who.int/health-topics/hearing-loss#tab=tab_1

Yew, K. S. (2014). Diagnostic approach to patients with tinnitus. American Family Physician, 89(2), 106-113.

Citation

Growling, B. (2023). 20Q: Audiology - there’s an art to this science. AudiologyOnline, Article 28333. Available at www.audiologyonline.com