, Sonomax Hearing Healthcare, Inc.

In addition to working to assess and remediate hearing loss, audiologists have a professional responsibility to prevent hearing loss from occurring if/when possible. Prevention of noise-induced hearing loss is an essential component of comprehensive hearing healthcare management, as reflected in the recent positions of the National Campaign for Hearing Health (https://www.hearinghealth.net/, look for Campaign Initiatives) and the World Council on Hearing Health (https://www.hearinghealth.net/cms/index.cfm?displayArticle=113). For many audiologists, noise-induced hearing loss prevewntion takes the form of dealing with industrial clients and their workers on hearing conservation issues.

The last, and all too often only, line of defense against noise in industry is the hearing protection device (HPD). We know these as earplugs, earmuffs, and similar devices used to protect people from the effects of excessive noise. HPDs and their use are mandated under certain conditions in US federal workplace safety regulations (29CFR1910.951, the federal Hearing Conservation Amendment). Understanding these devices, their capabilities, and the evaluation process used to assess their performance can help guide professionals and patients to appropriate application of this technology.

Many of the issues and barriers surrounding HPD use in the workplace were discussed in Hearing Protection: Prevention is the Answer, published by Audiology Online in November, 2002. The reader is referred via the following hyperlink; /articles/arc_disp.asp?catid=11&id=398.

Nonetheless, additional information and a general understanding of the nature of the HPD evaluation process will be beneficial for the selection of, and appropriate performance expectations for, HPD use.

How are HPD tested?

Two basic methodologies help determine how well HPDs work. The microphone in real ear (MIRE) method involves placing a miniature microphone in the ear canal behind the HPD. The difference between sound levels outside and inside the HPD indicates the noise reduction provided, and thus a sense of the protection the devices offer.

The MIRE approach can be difficult to use in real world day-to-day practice. Placing the measurement microphone in the ear canal typically necessitates running a cord from the mic out of the ear canal, either beneath or through the HPD. This can introduce an acoustic "leak" in the HPD, which can compromise performance. In addition, a purely acoustical measurement may not be the best HPD assessment. A simple measure of sound pressure level (SPL) outside the HPD minus SPL inside the HPD fails to account for the transfer function of the outer ear (TFOE) and other properties of the ear canal that affect the way sound is perceived by people.

The real-ear attenuation at threshold (REAT) test aims to address this issue. In the simplest terminology, REAT is an audiogram with HPD off, minus an audiogram with HPD on. The difference in thresholds describes HPD performance as perceived by the subject. Another explanation of these processes and their application is available from AEARO at https://earsc.com/; look for EARlog Number 1.

What are the governing standards and regulations?

In the USA an interesting combination of standards and regulations governs how HPDs are assessed. ANSI S12.6-1997 (R2002)2 is the most recent guidance provided by the professional standards community. It reflects laboratory procedures including an experimenter-fit process as well as a subject-fit approach.

Unfortunately, the regulatory community is not as up to date. In the USA, responsibility for HPD evaluation and labeling belongs to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under 40CFR211, Subpart B. This regulation references an earlier version of the ANSI standard, S3.19-1974. The direct reference to the 1974 standard in the EPA rule keeps HPD manufacturers "locked" into using an outdated procedure to evaluate their devices.

S3.19-1974 requires an REAT approach with a test panel of 10 subjects, three iterations of testing each. Findings are averaged by octave band, two standard deviations are subtracted, and with a bit more manipulation, these findings become the noise reduction rating (NRR) which EPA requires to be published on the HPD label as an indication of performance.

Many manufacturers feel compelled by market forces to maximize the NRR, with many consumers getting the message that "bigger is better". The net result is that lab experimenters legitimately optimize HPD performance by preparing and inserting the devices for each of their test subjects. While the process is fully allowed under the current rules, these test conditions do not represent "real world" processes and protocols. For example, the experimenter is able to see what they are doing and can typically maximally place the HPD in the correct position. Additionally, throughout the test, the subject is required to sit perfectly still in a test chamber sound field. No consideration is given to the requirements of real world jobs where people actually self-adjust and insert their HPDs. It's no wonder, then, that laboratory results do not coincide well well with field studies of HPD performance (see Hearing Protection: Prevention is the Answer, Audiology Online, November, 2002, /audiology/newroot/articles/arc_disp.asp?catid=11&id=398. )

What does OSHA require?

The Occupational Safety and Health Association (OSHA) hearing conservation regulation is based on the assumption that exposure to 90 dB of A-weighted decibels (90 dBA) or less, averaged over an 8-hour workday, is sufficiently safe for most workers. Therefore, HPDs must protect the worker to a time-weighted average (TWA) noise exposure of less than 90 dBA. OSHA makes special consideration for workers who exhibit sensitivity to noise. These people are defined as workers who experience a standard threshold shift (STS), an average 10 dB or more change in hearing at 2000, 3000, and 4000 hertz (hz), and they must be protected to 85 dBA TWA, giving them an additional 5 dB of protection.

OSHA also requires that noise-exposed employees receive annual training on the types of hearing protectors available, their use and care, and the advantages and disadvantages of each type.

What is "derating"?

OSHA uses the Noise Reducation Ratings (NRR) numbers two different ways.

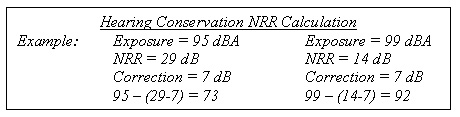

- When determining whether a given HPD is sufficient to protect a given worker in a given noise exposure situation, OSHA subtracts 7 dB from the NRR to correct for differences in the way noise is measured during the HPD evaluation (C-weighted noise) and the way noise exposure is commonly assessed in industry (A-weighted noise). If A-weighted noise exposure minus NRR minus 7 is 90 dB or less (or 85 dB for workers with STS, as above), the HPD is assumed to be sufficient. See examples.

- When comparing the efficacy of HPDs to noise reduction or noise control engineering, OSHA gives "credit" for the NRR minus the 7 dB correction; that result is then divided in half for a "50% derating". Thus, a 29 dB NRR HPD would be considered the same as an 11 dB reduction in noise exposure from noise control measures ((29-7)/2=11).

NIOSH has a different approach to managing NRR issues, they derate HPDs by type. Details are available at https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/noise/hpcomp.html, including a calculator to help select HPDs appropriate for various noise levels using the NIOSH derating system.

In practice, the combination of computations has proven too cumbersome for most of industry. Most have conservatively adopted a version of #2 (above) with a target protected level of 85 dBA TWA as a conservative performance requirement for HPD. This, of course, puts even more pressure on the HPD manufacturers to increase NRR, since they will be "credited" for less than half of the labeled value by many employers.

Is there change in the wind?

EPA has recognized some of the problems in their HPD evaluation process. Unfortunately, funding for the group within EPA responsible for this process, the Office of Noise Abatement and Control (ONAC), was eliminated in the early 1980's. Since there has been no funding, there has been no staff and thus no way to keep the standard up to date.

EPA held a workshop in March, 2003 to start the process of updating their references and moving the HPD evaluation process forward. When EPA opened the book on reconsidering their regulation, however, they found that the world of hearing protection had changed significantly since the last rule was adopted in 1979.

Innovative approaches to HPD attenuation evaluation have been developed. FitCheck from Michael & Associates (https://www.michaelassociates.com/) uses a combination of high-volume headphones and software to enable field assessment of insert HPD such as earplugs quickly and easily. Sonomax (www.sonomax.com) has adopted a modified MIRE approach to provide a functional fit test for each set of their custom molded hearing protectors as they are made.

New technology in electronic HPD has changed the landscape as well. Sound restoration earmuffs, like the Peltor Tactical 6S (https://www.aearo.com/pdf/comm/Tactical6-S.pdf) and Bilsom's 707 (https://www.bilsom.com/) provide amplification of quiet outside sounds and protection from excessive noise. Objective evaluation of HPD that amplifies as well as reduces noise has proven challenging.

Active noise cancellation is available in HPD from manufacturers like Bose (https://www.bose.com/), David Clark (https://www.davidclark.com/index.shtml) and Sennheiser (https://www.sennheiserusa.com/newsite/). This technology generates sound 180º out of phase with the offending signal to cancel sound.

Application is primarily limited to low frequency noises, making it well suited to aviation and some military applications, but not particularly useful for noisy, industrial applications. Evaluation of protection offered by devices designed to make noise to reduce noise has proven interesting.

The hearing protection device (HPD) continues to maintain key importance in the fight against noise-induced hearing loss in the workplace and elsewhere. Understanding how HPDs work, how they are evaluated and understanding realistic performance and protection expectations is very important for the audiologist dealing with noise-exposed clients, and is very important for workers trying to protect their hearing while using HPDs in noisy workplaces.

Recommended Readings:

The Noise Manual, 5th Edition, AIHA Press, Chapter 10. Information available at https://www.aiha.org/Pages/default.aspx

Preventing Occupational Hearing Loss: A Practical Guide, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 96-110, available free of charge from NIOSH Publications at [email protected], 1-800-35-NIOSH, or at https://www.cbs.com/

Criteria for a Recommended Standard: Occupational Noise Exposure, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 98-126, Section 1.5, 5.6, 6, and 7.6 available as above or at https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/98-126.html

https://www.hearinghealth.net for information on the National Campaign for Hearing Health

https://www.hearinghealth.net/cms/index.cfm?displayArticle=113 for information on the World Council on Hearing health

https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/noisehearingconservation/index.html for OSHA standards, interpretations and help on the noise regulation

https://earsc.com/ for the AEARO EARlog series of technical monographs on hearing protection issues

https://asa.aip.org/ for information on ANSI standards

https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/noise/ for information about workplace noise from NIOSH

https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/noise/hpcomp.html to connect with the NIOSH Hearing Protector Device Compendium, a list of hearing protectors and performance factors with calculator to help select

More information about new hearing protector and HPD evaluation technologies are available from these manufacturers.

https://www.michaelassociates.com/

https://www.sonomax.com

https://earsc.com/

https://www.bacou-dalloz.com

https://www.bose.com/

https://www.davidclark.com/index.shtml

https://www.sennheiserusa.com/newsite/

BIO:

Lee D. Hager works with Sonomax Hearing Healthcare, Inc., a leading provider of new technology in hearing loss prevention. He has been active in the field since 1986, with extensive professional association, presentation, publication, and field experience in hearing loss prevention approaches and techniques.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 OSHA hearing conservation standards, guidelines, and interpretations are available online at https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/noisehearingconservation/index.html

2 ANSI Acoustics standards are available from the Acoustical Society of America. Information is available at https://asa.aip.org/