Learning Outcomes

After this course learners will be able to:

- Describe the various components and their rational comprising Widex Zen Therapy.

- Describe the necessary components to provide comprehensive instructional counseling and cognitive-behavioral interventions to patients with tinnitus.

- Explain the results of recent investigations regarding the efficiency and efficacy of Widex Zen Therapy.

Introduction

For the past five years, I have been a strong advocate for Widex Zen Therapy (WZT). Released in 2012, Widex Zen Therapy provides hearing care professionals with systematic guidelines for tinnitus management, using Widex hearing aids equipped with Zen technology. Widex has developed a range of different elements and useful tools dedicated to client care. Today, I will provide an overview of the various components of Widex Zen Therapy.

Tinnitus Defined

Tinnitus comes from the Latin term tinniere, which means "to ring." When you ask someone with tinnitus to explain what they are experiencing, many will describe a ringing sound. Some will perceive it as more of a roaring sound. Others will choose the words clicking, chirping, humming, hissing or grating. All of these descriptors have been reported. It is important to note that patients suffering from tinnitus are not physically hearing these noises, as hearing requires sound. Tinnitus is not a sound; it is a phantom electrical signal.

Why Treat Tinnitus Patients?

There are a number of reasons why audiologists should treat tinnitus patients. First, tinnitus is very common. Approximately 15% of the world's population has tinnitus. More than 70% of hearing impaired individuals have experienced tinnitus at some point in their life. About 90% of tinnitus patients have some degree of hearing loss. Between 10 to 20% of people who have tinnitus seek out medical attention. Approximately 10% of the people who seek medical attention (1-2% of people with tinnitus) are so bothered by their tinnitus that it adversely affects their quality of life.

As an audiologist or a dispenser, treating this population reaffirms your expertise as someone who knows what to do with tinnitus patients. The reality is that most otolaryngologists prefer not to see tinnitus patients if they can avoid it, because they're often difficult to work with. They require a great deal of assistance, and there is a lot of emotional baggage that goes along with having tinnitus. However, it definitely provides an additional source of new patients, which is welcomed by many audiologists in today's world of over-the-counter hearing aids. Moreover, treating tinnitus patients is the ethical thing to do, particularly since many physicians either don't have the interest or the time to work with these patients.

Finally, treating tinnitus patients doesn't have to be complicated, but it's not for everyone. Just like not every audiologist is good with pediatric patients, not every audiologist is suited to treating tinnitus patients. Tinnitus patients will take up more time, require more visits and may take an emotional toll on the practitioner. The vast majority of audiologists have to have a basic understanding of tinnitus, so that they at least know what to say to patients and know when to refer the patients out for further assistance.

Subjective Assessment Scales

Tinnitus is subjective. As such, we must have some measure of how much it is bothering a person. There have been a number of subjective scales developed over the years, including the following:

- TSS: Tinnitus Severity Scale (Sweetow and Levy)

- THI: Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (Newman et al.)

- THQ: Tinnitus Handicap Questionnaire (Kuk et al.)

- TEQ: Tinnitus Effects Questionnaire (Hallam et al.)

- TRQ: Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (Wilson et al.)

- TCQ: Tinnitus Cognitive Questionnaire (Wilson and Henry)

- TPF: Tinnitus Primary Function Questionnaire (Tyler)

- TFI: Tinnitus Functional Index (Meikle et al.)

The one I prefer is the Tinnitus Functional Index, which has been very well researched. In my opinion, the weakest one of them all is this one at the top of the list, which was developed by Levy and me. However, it did lead to the development of other scales.

Intake Questionnaire

When we begin to see new patients, we use an intake questionnaire, through which we can gather information about the patient and how they are interpreting their tinnitus. We want to look at their audiogram and review the findings. We also want to educate the patient about the probable cause and the typical course of tinnitus, which often becomes less bothersome over time for the majority of people (about 80%). However, it's the 20% of patients who can't habituate and do not become accustomed to their tinnitus that we end up seeing. We want to provide proper reassurance that they're not dying. Again, in our training, we teach practitioners before they see tinnitus patients to make sure that there has been an MRI done, and that they've had all the proper lab tests. We want to discuss the patient's subjective assessment score with them, and use it as a baseline to compare how well they are progressing with therapy. We also try to bring in the patient's family members whenever possible.

Widex Zen Therapy

Widex Zen Therapy is a protocol; a series of steps for the hearing care professional to follow, in order to address the problems faced by tinnitus patients. If practitioners are going to be successful with tinnitus patients, they need this entire protocol, and they need to use a number of tools to achieve the desired outcome.

There are two levels of Widex Zen Therapy: basic and expert. Every audiologist should be able to attain the basic level so that they can counsel with a tinnitus patient and fit them with hearing aids that have acoustic tools. The expert level requires more extensive training that one can get through Widex, as well as through various courses around the world.

Difficulties Attributed to Tinnitus

People who suffer from tinnitus experience many difficulties, including:

- Sleep disruption

- Trouble understanding speech

- Despair, frustration, depression

- Annoyance, irritation, stress

- Concentration issues, confusion

- Drug dependence

- Pain/headaches

The most common problem, occurring in at least 50% of patients with tinnitus, is sleep difficulties. Many patients report that the tinnitus is interfering with their hearing, however it is more likely that it is interfering with their concentration. Despair and frustration are also common, leading to stress and depression. Many patients wind up becoming drug dependent. Some people report that they can feel the tinnitus, and that it gives them headaches.

Popular Theories of Tinnitus Origin

There are a variety of theories as to what causes tinnitus, some of which are not related to the auditory system. This may seem strange, but the more we learn about tinnitus, the more we realize the eventual cure is going to come from somewhere in the brain, outside of the auditory pathways.

Approximately 90% of people who have tinnitus also show some degree of hearing loss. It follows that the most common theory of the cause of tinnitus involves the disruption of auditory input (e.g., hearing loss) and resultant increased gain (activity) within the central auditory system (including the dorsal cochlear nucleus and auditory cortex). Any time there is a disruption in the auditory channels, the central nervous system increases its activity to try to compensate for what it expects to be receiving.

Another theory relates to homeostasis, which is defined as "the tendency of a system, especially the physiological system of higher animals, to maintain internal stability, owing to the coordinated response of its parts to any situation or stimulus that would tend to disturb its normal condition or function" (Dictionary.com). In people with tinnitus, neurons that have lost sensory input become more excitable and fire spontaneously, primarily because they have "homeostatic" mechanisms to maintain their overall firing rate constant (Bao et al., 2011). If these neurons fire enough, then it becomes a synchronized firing pattern which is perceived as a sound, or as tinnitus.

Most people begin to lose their hearing in the outer hair cells. As such, they experience a decrease in inhibitory (efferent) function, which is another potential cause of tinnitus.

Whenever you have hearing loss, it changes the number of neurons in your brain. The basal turn of the cochlea is tonotopically arranged so that it responds to high frequencies. If a person is not receiving any high frequencies due to hearing loss, the neurons in the cortex in that region of the brain lack stimulation. Those high frequency neurons need something to do, so they begin to respond to other sounds, such as mid-frequency sounds. Many people believe that this cortical plasticity may be a cause of tinnitus. However, there are people with normal hearing (i.e., they don't have cortical plasticity) who also have tinnitus. For example, people who have neck problems (due to whiplash from a car accident) or who grind their teeth tend to have what's called ephaptic transmission. Essentially, when they receive a stimulus, it becomes short circuited, and travels to the auditory cortex, instead of going all the way to the somatosensory cortex. If any type of stimulus (visual, auditory or tactile), ends up in the auditory cortex, it will be perceived as sound.

The limbic system is a set of structures in the brain that controls emotion, memories and arousal. It also contains regions that detect fear and threat. That may be a prerequisite for a person being bothered by tinnitus; it is not, however, a prerequisite for experiencing tinnitus. Everyone in this room may have experienced tinnitus for brief periods of time. When tinnitus becomes a problem to the extent that a person has trouble coping, this occurs because the limbic system becomes engaged in something that it ought not to be engaged in. This phantom signal, this tinnitus that's occurring because of increased central auditory activity, ought to be ignored.

Finally, one of the most interesting recent discoveries is that there may be some kind of a gate in the basal ganglia. The term basal ganglia refers to a group of subcortical nuclei responsible primarily for motor control, as well as other roles such as motor learning, executive functions and behaviors, and emotions. The basil ganglia have nothing to do with auditory pathways, however they seem to be responsible for blocking phantom signals. For example, if a person has their leg amputated, they may experience phantom leg syndrome, where they think that can still feel their foot itching. That's an example of a phantom signal that should be blocked. Tinnitus is another phantom signal that should be blocked before it reaches the cortex. Recent studies show that if the basal ganglia are impaired in any form, this gate may be opening up and allowing this phantom signal to get through. As tinnitus researchers look to the future, they may ultimately devise a way to keep the gate functioning properly, through neural modulation or some type of implant.

Tinnitus Therapies

All tinnitus therapies fall into three areas: limbic system engagement, auditory modality and auditory-striatal-limbic connectivity. All of these functional connections are occurring. If we could somehow alter these functional connections, we might be able to alter the tinnitus.

Limbic engagement. Limbic engagement works at getting the patient to reclassify how they perceive their tinnitus. Understandably, most anyone who experiences tinnitus views it in a negative way. We want the patient to be able to reduce the saliency, or the prominence of this signal. We want them to understand that the signal is not important and that it is something that can be ignored. We want to somehow mitigate or reduce the emotional distress associated with tinnitus. A number of therapies have been developed: tinnitus retraining therapy, neuromonics, Widex Zen Therapy, cognitive-behavioral intervention, mindfulness based stress reduction and anti-depressants. All of these methods are designed to alter how the limbic system classifies the tinnitus.

Auditory modality. There are things that be done within the auditory modality. For example, through a hearing aid-like apparatus, we could send in a masking noise, such as white noise or a narrow band of noise, that's centered around the perceived pitch of the tinnitus. Currently, hearing aids are probably the most effective way of dealing with tinnitus patients. At least 50% of people who simply put hearing aids on will say that they either don't hear their tinnitus any more, or that it has changed somehow, in loudness or in pitch. Also, there are ways you can program the hearing aid and things you can put into the hearing aid that will make them more effective. Neuromonics has been used for many years. It is a program that uses music; it plays two classical pieces and two new age pieces over and over, and they're shaped to accommodate the audiogram. Ideally, through listening to this music, you will alter the cortical map for which neurons are responding.

SoundCure S tones are an amplitude modulated signal that researchers in Southern California found to be very effective for cochlear implant patients who have tinnitus. By modulating an electrical signal going into the brain, they found that this can help a tinnitus patient. It hasn't been as effective with an acoustic signal. Although we're not going to put a cochlear implant on patients simply because they have tinnitus, it is a reasonable way to approach a person who has deafness as well as tinnitus. One of the components of Widex Zen therapy is fractal tones, which we will discuss in more detail coming up shortly.

Auditory-Striatal-Limbic Connectivity. Falling into the auditory-striatal-limbic connectivity category, striatal neuromodulation is where we either modulate part of the basal ganglia, or stimulate the vagal nerve. There's repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, which may alter how excitable the cortex is. There has also been some research using drug therapies to alter the potassium channel, although these have been largely ineffective. One of the drugs that has been looked at is called retigabine, which is an anticonvulsant used to treat epilepsy.

Limitations of Current Treatments

Unfortunately, there are limitations to these current treatments. With sound therapy, masking can be temporarily helpful in certain situations. For example, when a tinnitus patient is in the shower, they cannot hear their tinnutus. As soon as they get out of the shower, they will hear it again. It's similar to wearing devices that produce a white noise or a narrow band of noise; it will mask the tinnitus while they have it on, but when they take it off, their tinnitus comes back. Additionally, because the contrast is so great from the masking, the tinnitus becomes even more annoying. White noise has been shown to be effective for sleeping purposes. Neuromonics can become very boring for people, listening to the same sounds over and over. Patients will either habituate to those sounds or they may develop earworms.

One of the newer treatments to come out is a product called Desyncra. In Europe, this was called acoustic coordinated reset and it was used for Parkinson's patients. It is now being used for tinnitus patients. It's a set of headphones that one can use that will match the tinnitus, which by the way is not an easy task because it's very variable. If you match the tinnitus day after day, most people will not be able to find exact same pitch. However, if you do match the tinnitus, Desyncra is based on the concept that tinnitus is a synchronization of this spontaneous firing. They use an algorithm that produces two other tones based on your audiogram. The concept is that it will now de-synchronize this abnormally synchronized firing.

Tinnitus retraining therapy (TRT) has been popular for a long time. Now, because of new approaches, it is becoming less popular. TRT uses two components to target the limbic system: auditory stimulation and counseling. Cognitive-behavioral therapy is probably the most effective counseling approach used today. I will talk further about that, because it is an important component of Widex Zen Therapy. In the future, neuromodulation may be an effective solution for treating tinnitus if it can be better developed. However, it involves stimulating the basal ganglia using electrodes; at present, not too many people are volunteering to have their brains drilled into for experimental treatments.

Most people with tinnitus have hearing loss. Of all of the treatment approaches we just discussed, none of them provide amplification. If we can provide amplification, along with some kind of acoustic stimulus, then we might be able to conquer two aspects of the tinnitus therapy triangle at once.

Components of Widex Zen Therapy

The components of Widex Zen Therapy are:

- Counseling

- Amplification

- Fractal Tones

- Relaxation

Additionally, based on recent research, I would also recommend physical exercise. Physical exercise has been shown to have a positive effect on the pre-frontal cortex, and the pre-frontal cortex has a tremendous effect on the limbic system.

Counseling

The purpose of counseling is to educate the patient about tinnitus, and to assist their limbic system to alter its negative interpretation of the tinnitus. This is achieved through cognitive and behavioral intervention. We teach a person strategies to use when they're having difficulty coping with their tinnitus. Counseling consists of two major components: instructional counseling and adjustment-based counseling.

Instructional counseling. Instructional counseling is one of the components of tinnitus retraining therapy. With instructional counseling, we provide the patient information about tinnitus, such as the basic anatomy and physiology of their auditory and their central nervous system, why they have tinnitus, and that (in most cases) their tinnitus is secondary to their hearing loss. This is important because if a patient comes in and says, "I have tinnitus, what can you do for me?" and if the audiologist tells them, "We're going to put hearing aids on you," the patient gets very upset. They may erroneously believe that you're trying to sell them hearing aids, and that's not our intent. Everyone I teach, I instruct them to first talk about the tinnitus, then explain why this lack of auditory stimulation creates the tinnitus. At that point, it becomes easier to tell them that if we can give them back more auditory stimulation, they might be able to minimize the impact of the tinnitus. That's where we would introduce the hearing aids. The logical course of tinnitus is that for most people, they become accustomed to it over time. It's there but they don't even think about it, because it just becomes part of their life.

During our counseling time, we also talk about how the limbic system affects the tinnitus perception, and how the patient's reaction impacts the ability to cope with or habituate to the tinnitus. This is designed to get the person to ignore their tinnitus, because it's not important. It's not an indicator that something is wrong. The idea is that, from a psychological perspective, to adapt or reduce a conditioned response (which is what your reaction to tinnitus becomes), you have to give the stimulus following repeated exposure. In other words, if you mask out the tinnitus, the person is not being exposed to the tinnitus because they don't hear it, and therefore they will never habituate to it. Through exposure to the tinnitus, and through counseling, the patient's brain will eventually recognize that they are not in a dangerous stimulation, and they will be able to suppress it.

The way that the brain habituates to tinnitus is very interesting. When a sound goes through your cochlea (e.g., loud thunder during a storm), it travels up your auditory cortex. Your auditory cortex analyzes the signal based on how many nerves are firing and how fast they are firing. The auditory cortex sends that information to the hippocampus. The hippocampus identifies the sound as thunder. It then asks the amygdala, "Do I need to listen to that thunder? Is it important?" The amygdala responds, "No, it's not important. Go back to sleep." Your brain automatically suppresses it and you can sleep through this very intense auditory signal. Now, change the scenario and pretend you're lying in bed and all of a sudden you hear a soft squeaking sound coming from the next room. You realize that there's no one in the next room. You wonder, "Why is the floor squeaking? Could it be a burglar or robber?" Your amygdala alerts you that this could be trouble, and to pay attention to it. Now your attention is focused on that signal and with every successive squeak, you hear it more and more. Suddenly, you realize that you are watching the neighbor's dog, and that the dog is making the noise. The amygdala will then say, "No problem, no threat, forget it." Why is this an important example? It demonstrates that it's not the loudness of the signal that creates the attention: it's the meaning of the signal. In some cases, you can ignore a loud signal, such as thunder. In other cases, when you hear a soft signal, you cannot ignore it.

Adjustment-based counseling. Adjustment-based counseling is even more important than instructional counseling. Adjustment-based counseling focuses on the impact tinnitus has on a person's emotional life. Are they becoming anxious? Are they becoming depressed? Are they becoming drug dependent? How is it affecting them? We want to address these emotional stimuli. We also want to identify and correct any maladaptive thoughts that could potentially make things worse. Many patients believe that they are going to die from their tinnitus. They can't sleep, they can't concentrate, they can't hear properly. All these terrible things are happening, to the point that they believe they have an auditory tumor and they are going to die. Or, they may think they are going crazy because no one else hears this signal. When you have fearful thoughts like that, it re-engages the limbic system. The amygdala keeps saying, "Maybe you do have a real problem here; let's pay attention to this." As a result, the person continually pays attention to this tinnitus. We want to identify these thought patterns that prevent a person from going through the natural habituation process that 80% of tinnitus sufferers go through.

We want the patient to understand the relationship between the tinnitus and stress. There are ways of altering that relationship by challenging the way they think about the tinnitus, using an approach called cognitive behavioral intervention, which is inspired by cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). CBT was developed a long time ago for chronic pain. In general, audiologists are not trained to do CBT, which is normally provided by mental health professionals. However, cognitive behavioral intervention is designed to identify the unwanted thoughts and behaviors hindering natural habituation, challenge their validity, and replace them with alternative and logical thoughts and behaviors. The objective of cognitive behavioral intervention is to remove inappropriate beliefs, anxieties and fears, and to help the patient recognize that it is not the tinnitus itself that is producing these beliefs, it is the patient's reaction, and all reactions are subject to modification.

Amplification

Another component of Widex Zen Therapy is amplification. Amplification is usually done binaurally, when appropriate. The idea is if we stimulate the cochlea, presumably the central nervous system will not have to compensate for what it is missing. Central nervous system activity decreases with stimulation, which the opposite of what you might think. When I started in audiology, I was always taught that if you have a hearing loss, you have less activity at the cortex, but it's just the opposite: you have more activity at the cortex. Again, that could be very important with the proper amplification.

By providing more stimulus to the cochlea, we can reduce the excess hyperactivity in the cortex. The reality is that most well-fitted, high quality hearing aids can help tinnitus patients with hearing loss. However, the number one thing that you want in a hearing aid is the lowest compression knee point possible, because you don't want the person to be in silence. If they're in silence, they hear their tinnitus. If they're around other noises, they don't hear their tinnitus as much. With a low compression point, you're giving gain to very low inputs. Widex hearing aids have the lowest compression thresholds in the industry. Additionally, Widex hearing aids have a very broad bandwidth, as well as a precise fitting process (Sensogram) and in situ verification (Sound Tracker). Widex hearing aids are not the only product on the market that will help a tinnitus patient, but they happen to be particularly useful for this purpose.

Fractal Tones

Stress is probably an even more important factor than noise exposure for transforming a person from someone who simply has tinnitus, to someone who is horribly bothered by their tinnitus. What do we commonly do when we experience stress? We listen to music. Music has been shown to activate the limbic system and other brain structures (including the frontal lobe and cerebellum) and has been shown to produce physiologic changes associated with relaxation and stress relief. Based on this fact, another component of Widex Zen Therapy is to use fractal tones, which are available in all of Widex's newer hearing aids, including Unique, Dream, Mind, Clear and Beyond.

Auditory fractal tones utilize harmonic but not predictable relationships, somewhat like wind chimes. Originally, the purpose of fractal tones was to help a hearing-impaired patient relax, as they have higher levels of stress than a normal hearing person. Fractal tones are now used to deliver pleasant stimuli to the tinnitus patient in a discreet, inconspicuous manner. Again, we're trying to both relax the patient and help them with their tinnitus.

Widex is the first company to use fractal tones to help tinnitus patients. Fractal tones are dynamically varying signals with semi-random temporal modulations. They create a melodic chain of tones that repeat enough to sound familiar and follow appropriate rules, but vary enough to not be predictable. Fractal technology ensures that no sudden changes occur in tonality or tempo. Widex Zen is an optional listening program in most Widex hearing aids that is based on an algorithm of non-repetition and non-predictability. Therefore, the person can't memorize what's about to happen. Patients can hear the fractal tones, but they do not pay attention to them, and that's the effect we want.

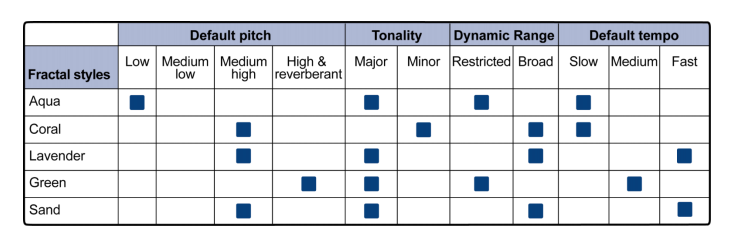

If the patient chooses to use Zen, they will hear adjustable, continuous, chime-like tone sounds using fractal algorithms. The chimes are generated based on an understanding of the properties of music that would be most relaxing (Robb et al., 1995). Each patient has the ability to self-select music in a variety of pitches. Through experiments, we have found that most people prefer a slower tempo that goes along approximately at the rate of a heartbeat (between 60 and 74 beats per minute). That's probably the most relaxing tempo, but there are some people who like a faster tempo. There are five fractal styles to choose from: aqua, coral, lavender, green and sand (Figure 1). Each style has different tonality (major or minor chords), dynamic range (restricted or broad) and tempo (slow, medium or fast).

Figure 1. Fractal styles.

The reality is that not everyone likes fractal tones; some people even find them annoying. In addition to the fractal tones, Widex hearing aids also include frequency shaped noise and a filter that allows you to adjust the noise.

Relaxation

The fourth component is a relaxation strategy program. The aim is to teach the patient basic relaxation skills, because we know that stress and tinnitus are very highly correlated. We want the patient to perform these simple relaxation exercises as they're learning how to cope with their tinnitus and reassign interpretation to the tinnitus.

There are three basic relaxation exercises that we can teach as a part of Widex Zen Therapy: progressive muscle relaxation, deep breathing and guided imagery. These three methods employ the benefits of self-hypnosis, or deep relaxation. If you relax, the likelihood of your tinnitus being louder is diminished, and your reaction to the tinnitus will be more positive.

Progressive muscle relaxation. Progressive muscle relaxation is a means of alternately tensing and relaxing different muscle groups (e.g., neck muscles, shoulder muscles, stomach muscles, hands). We teach a person to tense those parts of their body, hold it for a few seconds and then relax. We teach patients how to recognize the difference between what their body feels like when they are tensing certain muscles as compared to when they are relaxing those muscles. It doesn't take long to realize where you're manifesting tension.

Deep breathing. Deep breathing relaxation techniques work particularly well. Remember when you were younger, and if you were having a temper tantrum, your mother would say, "Slow down, take some deep breaths." There is a medical reason for that, and it has to do with the compression on the vagal nerve. Deep breathing is something that can easily be taught. Slowly inhale through your nose, count to four or five, hold your breath for a few seconds and then slowly exhale out of your mouth. If you do this 20 times in a row, based on physiology, you will relax.

Guided imagery. Guided imagery is a means of visualizing a wonderfully relaxing situation. For example, you may find that walking in the forest is very relaxing. You're going to close your eyes, do some deep breathing and visualize walking along a forest path using every one of your senses: smell, sound, sight, taste and touch.

Personalizing WZT

When an audiologist is going to begin using Widex Zen Therapy, they must first determine the level of severity of each patient. To determine the patient's score, the audiologist can administer any of these subjective scales that we reviewed earlier (TFI, THI, THQ, TRQ). Using a scale from 0-100, the higher the patient's score, the more components you will need to add to that patient's Widex Zen Therapy regimen.

- Level 1 (0-17): Minimal or no negative tinnitus reaction

- Instructional Counseling

- Amplification (when hearing loss exists)

- Zen fractal tones might be useful for quiet environments

- Level 2 (18-36): Mild negative tinnitus reaction

- Instructional Counseling

- Amplification (when hearing loss exists)

- Zen fractal tones for quiet environments

- Level 3 (37-57): Moderate negative tinnitus reaction

- Instructional Counseling

- Cognitive behavioral intervention

- Amplification/avoidance of silence

- Zen fractal tones all day

- Relaxation exercises might be useful

- Level 4 (58-76): Severe negative tinnitus reaction

- Instructional Counseling

- Cognitive behavioral intervention

- Amplification/avoidance of silence

- Zen fractal tones all day

- Relaxation exercises

- Level 5 (77+): Catastrophic tinnitus reaction with or without hearing loss

- Instructional Counseling

- Cognitive behavioral Intervention

- Amplification/avoidance of silence

- Zen fractal tones all day

- Relaxation exercises 2-3 times a day

As I mentioned earlier, I would also suggest adding some form of physical exercise, because there is functional connectivity between the limbic system and the frontal lobe and the auditory/somatosensory cortex.

Improvement

What is considered improvement? An improvement can be measured by the following milestones:

- Reduction in the number of episodes of awareness: how many times per day the patient notices their tinnitus.

- Increase in the intervals between episodes of awareness

- Increase in perceived quality of life

We do not measure improvement based on a patient's perceived reduction in loudness. We do need to make sure the patient understands that the effects of therapy may not be immediate, and to establish realistic, time-based expectations.

Evidence-Based Research on WZT

After I stepped down from my position at the UCSF, I came to consult with Widex. I was impressed that of all the hearing aid companies, Widex was the one company that based all of their decisions on evidence and research. Everything that I've told you so far about the Widex Zen Therapy is based on evidence. Due to time constraints, today I am going to highlight just a few of these studies by briefly reviewing some of the conclusions and findings. As evidenced in each one of these studies, the difference between the Widex approach and other tinnitus approaches is that the biggest change that a person experiences is in the first two to three months. After that, the changes do slow down a bit, but all the other approaches take several months before the person sees an impact.

Sweetow and Henderson-Sabes, 2010

This was a study that we did at UCSF in 2010. We adminstered the THI (Tinnitus Handicap Inventory) and the TRQ (Tinnitus Research Questionnaire) before treatment, and at 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months while using Zen. Over time, there was a gradual decrease in the subjects' perceived tinnitus severity. Our conclusion was that Zen is an effective tool for promoting relaxation. We had 14 subjects with severe tinnitus, and 86% of them indicated that it was easier to relax while listening to the fractal signals. They found Zen to be an effective tool for promoting tinnitus reduction. They found that both the fractal tones and the noise were effective for tinnitus reduction, but over the long term, people didn't want to listen to the noise. They liked listening to the fractal tones on a daily basis, because they were more relaxing than the noise.

Sekiya et al., 2013

This was a study conducted in Japan by a gentleman who was very well versed in tinnitus retraining therapy. His findings were as follows:

- A good effect was obtained when using fractal music within a TRT treatment.

- Improvements in THI scores were observed after 6 months in 92% of patients who used fractal music as sound therapy.

- A flexible combination of sound stimuli is particularly useful in difficult cases where TRT with conventional sound therapy does not produce the desired effect.

- Combination devices are sometimes an effective way of introducing amplification to reluctant hearing aid candidates.

Sweetow, Fehl and Ramos, 2015

In this study, we wanted to see if once a person begins to habituate, if they continue to use amplification and sound therapy. In other words, if a patient's main problem was tinnitus rather than hearing loss, but they do have some hearing loss, once they habituate, will they still stay with the hearing aids? We found that once they habituated, they started using the fractal tones less but they used the hearing aids more. Again, people who didn't think that hearing loss was an issue continued to use the amplification, even after we achieved our objective, which was habituation for their tinnitus.

Sweetow, Kuk and Caparoli, 2015

In 2015, some colleagues and I conducted a randomized controlled study on the effects of integrated tinnitus therapy with fractal tones on subjects with normal hearing or minimal loss. Once again, we found that the improvement lasts at least for 12 months. Patients' THI scores improved significantly. Using a control group or waiting list group in this situation, there was minimal or no change before they started getting the Widex Zen Therapy. However, once they got the Zen Therapy, then all of a sudden we saw this very significant change.

Summary and Conclusion

To sum up what we have learned, tinnitus patients with hearing loss may best be served by amplification that incorporates low compression thresholds, a broad frequency response, and flexible options for acoustic stimuli. In addition, it is important to tailor the therapy to the patient’s functional and financial needs. Finally, sound therapy without counseling is not likely to work.

In conclusion, whatever approach you choose to use, patients will not regard therapeutic programs to be viable unless the clinician believes they are. The clinician must have buy-in and believe in the process, which will work when done properly. If you have passion for this process, so will the patient.

Questions and Answers

Can training be done when you're sleeping?

I don't think there have been enough studies. I can tell you that the only people who did studies on many of the tinnitus products available today were the inventors of those processes, so you have to critically evaluate the validity of those studies. Many studies in tinnitus have a very low number of subjects. A lot of studies have been done on Widex Zen Therapy, but more studies still need to be done to demonstrate the effects on the brain and things like that. Many of these so-called tinnitus "therapies" or "cures" that come out are around for three, four or five years and then they disappear. Some have been around for 15 to 20 years, but if they were effective, they would have more widespread use. With the Widex Zen Therapy, we as a company have got to train the clinicians to understand it and to not be afraid of this. I do think that there may be some merit to providing acoustic stimulation while the person is sleeping, but time will tell as more studies are done in this area.

References

Hallam, R.S., Jakes, S.C., & Hinchcliffe, R. (1988). Cognitive variables in tinnitus annoyance. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 27, 213-222.

Herzfeld, M., Enza, C., & Sweetow, R. (2014). Clinical trial on the effectiveness of Widex Zen Therapy for tinnitus. Hearing Review, 21(11), 24-29.

Herzfeld, M., & Kuk, F. (2011): A clinician’s experience with using fractal music for tinnitus management. Hearing Review, 18(11).

Kuk, F., Peeters, H. & Lau, C. (2010): The efficacy of fractal music employed in hearing aids for tinnitus management. Hearing Review, 17(10).

Kuk, F., Tyler, R., Russell, D., & Jordan, H.Y. (1990). The psychometric properties of tinnitus handicap questionnaire. Ear and Hearing, 11, 434-445.

Meikle, M.B., Henry, J.A., Griest, S.E., Stewart, B.J., Abrams, H.B., McArdle, R.,...Vernon, J.A. (2012). The tinnitus functional index: development of a new clinical measure for chronic, intrusive tinnitus. Ear and Hearing, 33(2), 153-76.

Newman, C.W., Jacobson, G.P., & Spitzer, J.B. (1996). Development of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Archives of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, 122(2),143-148. doi:10.1001/archotol.1996.01890140029007

Sekiya, Y., Takahashi, M., Kabaya, K., Murakami, S., & Yoshioka, M. (2013, March). Using fractal music as sound therapy in TRT treatment. AudiologyOnline, Article #11623. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com

Sweetow, R., Fehl, M., & Ramos, P. (2015). Do tinnitus patients continue to use amplification and sound therapy post habituation? Hearing Review, 21(3), 34.

Sweetow, R., Kuk, F., & Caporali, S. (2015). A controlled study on the effectiveness of fractal tones on subjects with minimal need for amplification. Hearing Review, 22(9), 30.

Sweetow, R., & Levy, M. (1990). Tinnitus severity scaling for diagnostic and therapeutic usage. Hearing Instruments, 41, 20-21, 46.

Sweetow, R.W., & Sabes, J.H. (2010). Effects of acoustical stimuli delivered through hearing aids on tinnitus. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 21(7), 461-473.

Wilson, P., Henry, J., Bowen, M., & Haralambous, G. (1991). Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire: Psychometric properties of a measure of distress associated with tinnitus. Journal of Speech & Hearing Research, 34, 197-201.

Citation

Sweetow, R. (2018, January). Why treat tinnitus patients. AudiologyOnline, Article 21616. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com