Question

What is the link between cognition and hearing loss?

Answer

Cognition, Hearing Loss, and Why It Matters

Discussions about the mind-brain connection have increased over the years, driven by enhanced research and growing curiosity regarding neurophysiology and neuroanatomy. When you hear the word "brain," you probably think of the three-pound structure that houses billions of neurons, allowing us to breathe, walk, talk, see, taste, smell, feel, think, and, likely, hear—perhaps a hearing care professional’s favorite sense. These abilities can be categorized under the umbrella of cognition. Our patients might think of cognition as the ability to think, make decisions, and carry on conversations. While they’re not entirely wrong, we hearing healthcare professionals have learned that cognition represents the mental processes occurring in the brain, including thinking, attention, language, learning, memory, reasoning, executive function, and perception.1 These mental processes are not independent of each other; rather, they form an ecosystem of processes that make us human. They enable us to form real, human connections, provided our five senses are functioning properly.

But what happens when cognition is adversely affected by a stroke, traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer's disease, mild cognitive impairment, or untreated hearing loss, which is the third most common potentially modifiable risk factor? A patient's hearing, speech, language, communication, attention, and interpersonal relationships can, and often are, negatively impacted. To date, over 44 million Americans present with hearing loss on an audiogram, while another 26-30 million Americans have normal hearing thresholds but struggle to understand speech in complex listening situations.2,3 In September 2023, findings from The Aging and Cognitive Health Evaluation in Elders (ACHIEVE) study were released. The study reported that in older adults at increased risk for cognitive decline, hearing intervention slowed the loss of thinking and memory abilities by 48% over 3 years.2 Additionally, the ENHANCE study found that hearing aid users demonstrated significantly better cognitive performance up to 3 years post-fitting, suggesting that hearing intervention may delay cognitive decline or dementia onset in older adults.4

As it relates to the ACHIEVE study, much to the disappointment of many hearing care providers, the main effect of amplification did not preserve cognitive function when compared to the control group, which was matched for the degree of hearing loss, age, and various other demographic factors. However, a promising result emerged for a specific subgroup at risk of cardiovascular disease—the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC). In this population, which comprised individuals with hearing loss, aging, and increased risk factors for heart disease and stroke, hearing aid intervention was associated with a 48% reduction observed over 3 years in cognitive change compared with the control group. Results from this first-of-its-kind randomized trial add to the growing evidence that suggests addressing modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia could be effective in reducing the future global burden of dementia. For those aging individuals with hearing loss and elevated risk of stroke or cardiovascular disease, it is important not to simply accept untreated hearing as an acceptable consequence of aging.

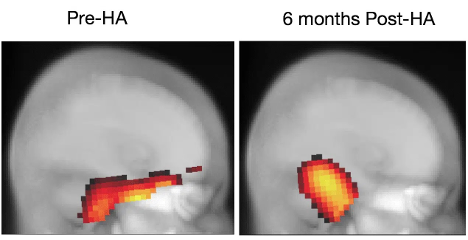

An increasing body of literature is highlighting the connection between untreated hearing loss and cognitive decline. However, how often do you encounter patients each month who present with hearing loss alone, without any other sensory impairment such as vision loss? Let’s take it a step further and discuss dual sensory impairment (DSI) as it relates to cognition. Dumassais et. al. report that DSI, the combination of visual and hearing impairments, is associated with increased risk for age-related cognitive decline and dementia.5 When two senses are impaired, this places additional stress on the brain, and cross-modal recruitment may take place. Unlike weightlifting, where you place your muscles and body under stress to strengthen muscles and improve body composition, DSI has the opposite effect, potentially leading to reduced listening effort and cognitive decline. Glick and Sharma (2017) released a publication titled “Cross-Modal Re-Organization in Clinical Populations with Hearing Loss.”6 Dr. Sharma reported in a Hearing Review interview that, as shown in Figure 1, clinical treatment with hearing aids resulted in a reversal of cross-modal reorganization of the auditory cortex by vision in the ARHL group. Further, the reversal of cross-modal reorganization coincided with gains in speech perception and cognitive performance.”7

Figure 1. Brain changes before and after hearing aid use: In the left panel, we see evidence of cross-modal recruitment of temporal (auditory) cortex recruitment by vision and frontal cortex activation suggestive of effortful listening. In the right panel, after 6 months of hearing aid use, we see reversal of cross-modal and frontal recruitment representing more typical activation of cerebellar and occipital (visual) cortex in response to a visual motion stimulus.

As hearing healthcare professionals, we have the unique opportunity to help reconnect patients with their friends, family, and communities. However, hearing aids are just one part of the equation. Where does aural rehabilitation (AR) fit into the patient’s journey? Who should be part of the AR team, and is it necessary for us to incorporate cognitive screenings into our clinics?

Aural Rehabilitation Strategies: Counseling is Paramount

Montano (2014) defined AR as a person-centered approach to assessment and management of hearing loss that encourages the creation of a therapeutic environment conducive to a shared decision process which is necessary to explore and reduce the impact of hearing loss on communication, activities, and participation.8 When working with our patients, we’re not just managing their hearing loss. We’re introducing them to a new hearing world, where their sensory abilities will be both enhanced and challenged. While their hearing and listening abilities will improve, this new world may also bring challenges that they can overcome with AR — provided by you, the hearing healthcare professional.

The person sitting in front of you in the clinic is much more than just their hearing loss. We should not treat hearing loss in isolation. Rather, hearing care professionals should implement a person and family-centered approach when delivering AR.8 While there has been debate regarding whether hearing care professionals should administer cognitive screenings, we believe they should, provided they are adequately trained and thoroughly familiar with the selected cognitive screener. A comprehensive case history, thorough assessment, and counseling are critical. What is the patient’s current level of social activity? Do they/their family member(s) report difficulty with memory? Are they socially withdrawing due to their hearing loss, or is there an underlying comorbidity we are unaware of?

When we are fitting patients with their hearing technology, we need to be cognizant of the fact that these patients are learning new fine motor sequences, and their attention and memory will be required to assist in a successful hearing aid fitting. Including the patient’s family member(s), spouse, or partner, oftentimes shortens the learning curve. In closing, outcome measures like the Abbreviated Profile of Hearing Aid Benefit (APHAB) and the Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) are support tools that provide hearing healthcare professionals with more “color” as it relates to the patient’s perceived hearing aid benefit. If a patient presents with cognitive decline, outcome measurements may not be feasible; however, this can be ruled out following a comprehensive case history and assessment.

Emerging Audiological Technologies to Support Cognitive Function

In 2018, Starkey was the first to incorporate inertial measurement units (IMUs) in their hearing aids. Hearing loss does not occur in a vacuum. In many cases, hearing loss is highly correlated with cardiovascular disease, cognitive decline, increased risk of falls, vision loss, and a host of comorbidities. The older you get, the more likely you are to have DSI. Think of sound as nutrition for the brain. PET scans have shown that if we deprive certain frequency regions from going to the brain, over time those areas start mapping out to do other functions. When you fit a patient with hearing aids, some of those regions can recover, but what we've seen from the work by Glick, Sharma, and others has shown promising results of the benefit of amplification over time.

Job one of every hearing aid is to amplify sound appropriately for the patient and their hearing loss. In 2018, Starkey put IMUs in their hearing technology to track activity. At the time we were fond of saying the “Ear is the New Wrist” because we could track steps and patient movement, which is good for musculoskeletal strength in the aging population. However, what you can't do on the wrist is report a socialization score. Not only is it important that people wear their hearing aids every day to make sure that you're feeding the brain an adequate diet of sound but also ensuring that they are engaging in conversation with other people. We “gamified” socialization and we've continued to enhance those social and physical aspects. Not because we can, but because we need to; because there is such a high comorbidity between cognitive function, cardiovascular disease, fitness, and hearing loss. We have also made great strides with balance in partnership with Stanford University.9 We know that even a mild degree of hearing loss elevates risk of falling by three times.10

A fall detection feature is great, but if a person breaks a limb, especially their hip, it often starts that downward spiral of health. Just this last year, Starkey introduced a balance risk assessment, which also uses the IMUs to assess gait, strength, and balance deficits that people can do in the comfort of their own home. They can run these measurements that were developed by the Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths and Injury - STEADI protocol developed by the CDC and enable them to test their baseline. If they identify a risk in balance, gait, or strength, they could see a physical therapist or primary care physician, engage in physical therapy to address the deficit, and then monitor their progress over time to hopefully prevent falls before they occur.

It’s a well-established fact that the audiogram, as important and vital as it is in discerning whether someone has measurable hearing loss, hasn’t seen any innovation in 100 years. With people who have minimal hearing loss, due to improvements in technology, or situationally, we've considered both adults and children using a remote microphone with a low-power device that places the microphone closer to the person of interest, whether that’s a teacher in a classroom or a partner or family member dining in a restaurant. These assistive technologies can help with situational difficulty, especially in background noise. Increasingly, many of us are encouraging people to think outside the box—if the box is the test booth, start thinking about real-world environments where noise is more present, or do speech-in-noise testing to see if someone with a supra-threshold level has difficulty hearing in noise.11

With new technology available, more people can be helped than ever before. An important detail from the ACHIEVE study is that all subjects in the group that wore hearing aids over three years reported less loneliness and better social engagement than the control group, which is often a precursor to depression, social isolation, and even cognitive decline. We see this in family members and friends—social people who suddenly had difficulty in noisy environments, stopped going to those environments, and became exhausted when their partners were talking about how great the evening was. The partner with some hearing loss was processing it as fatigue and gradually withdrew, contributing to social isolation, loneliness, depression, and possibly cognitive decline.

Today's technology offers us the opportunity to treat hearing loss better than we ever have before and offer patients new ways to hear better and live better. The science is clear: untreated hearing loss increases the risk of multiple neurological and physical ailments. Why not offer your patients the fullest extent of the technology we have at our fingertips?

Inventis: Advancing Audiological Solutions

At Inventis, we are committed to providing cutting-edge audiological solutions that integrate the latest advancements in hearing research. Our goal is to ensure that professionals have access to the most advanced tools to enhance patient outcomes and improve overall hearing care. By leveraging research-backed technologies, Inventis supports clinicians in delivering comprehensive and innovative care to individuals experiencing hearing-related challenges.

Conclusion

Today's technology offers us the opportunity to treat hearing loss better than ever before and offer patients new ways to hear and live better. The science is clear: untreated hearing loss increases the risk of multiple neurological and physical ailments. By ensuring clinicians have the right tools and technology at their disposal, we can significantly improve patient care and long-term quality of life.

References

Dementias Platform UK. (n.d.). What is cognition? Dementias Platform UK. Retrieved January 30, 2025, from https://www.dementiasplatform.uk/news-and-media/blog/what-is-cognition#:~:text=Cognition is a term for,to function as healthy adults

Lin, F. R., Pike, J. R., Albert, M. S., Arnold, M., Burgard, S., Chisolm, T., Couper, D., Deal, J. A., Goman, A. M., Glynn, N. W., Gmelin, T., Gravens-Mueller, L., Hayden, K. M., Huang, A. R., Knopman, D., Mitchell, C. M., Mosley, T., Pankow, J. S., Reed, N. S., Sanchez, V., … ACHIEVE Collaborative Research Group. (2023). Hearing intervention versus health education control to reduce cognitive decline in older adults with hearing loss in the USA (ACHIEVE): A multicentre, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 402(10404), 786–797. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01406-X

Hearing Review. (2022, August 30). Audiologic considerations for people with normal hearing sensitivity yet hearing difficulty and/or speech-in-noise problems. Hearing Review. Retrieved January 30, 2025, from https://hearingreview.com/hearing-loss/patient-care/evaluation/audiologic-considerations-people-normal-hearing-sensitivity-yet-hearing-difficulty-andor-speech-noise-problems

Sarant, J. Z., Busby, P. A., Schembri, A. J., Fowler, C., & Harris, D. C. (2024). ENHANCE: A comparative prospective longitudinal study of cognitive outcomes after three years of hearing aid use in older adults. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 15, 1302185. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2023.1302185

Dumassais, S., Pichora-Fuller, M. K., Guthrie, D., Phillips, N. A., Savundranayagam, M., & Wittich, W. (2024). Strategies used during the cognitive evaluation of older adults with dual sensory impairment: A scoping review. Age and Ageing, 53(3), afae051. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afae051

Glick, H., & Sharma, A. (2017). Cross-modal plasticity in developmental and age-related hearing loss: Clinical implications. Hearing Research, 343, 191–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2016.08.012

Hearing Review. (2023, January 17). How might the brain change when we reintroduce sound? Hearing Review. Retrieved January 30, 2025, from https://hearingreview.com/inside-hearing/research/how-might-the-brain-change-when-we-reintroduce-sound

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (n.d.). Aural rehabilitation for adults. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Retrieved January 30, 2025, from https://www.asha.org/practice-portal/professional-issues/aural-rehabilitation-for-adults/?srsltid=AfmBOorIMZOgFPXEQHoor7xS3tk1HbotgusqvrHyCdpaZMLXMoPehvpP

Steenerson, K. K., Griswold, B., Keating, D. P., 3rd, Srour, M., Burwinkel, J. R., Isanhart, E., Ma, Y., Fabry, D. A., Bhowmik, A. K., Jackler, R. K., & Fitzgerald, M. B. (2025). Use of hearing aids embedded with inertial sensors and artificial intelligence to identify patients at risk for falling. Otology & Neurotology, 46(2), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000004386

Starkey Hearing Technologies. (2017, December). Likely to fall with hearing loss. Starkey Hearing Technologies. Retrieved January 30, 2025, from https://www.starkey.com/blog/articles/2017/12/Likely-to-fall-with-hearing-loss#:~:text=Falls are some of the,or by clicking here today

Resources for More Information

For more information about Inventis, visit https://www.inventis.it/en-na