The Audibility Index: An Indispensable Counseling Tool for Modern Hearing Clinics

AudiologyOnline: What is the Audibility Index?

Clayton Fisher: The Audibility Index (AI), also known as the Articulation Index, simply calculates what percentage of an average speech signal is audible to a person. The Audibility Index is the more accurate and appropriate term, however, the term Articulation Index is still used colloquially. Similarly, the Audibility Index (AI) and the Speech Intelligibility Index (SII) refer to the same concept, albeit with different nomenclature.

AudiologyOnline: How is the AI calculated?

Clayton Fisher: For decades this was done manually by using Killion and Mueller’s powerful and easy-to-use clinical tool, the ubiquitous “Count the Dots” audiogram. In recent years, modern audiometry suites, such as Maestro software, by Inventis, have made life even easier by calculating the AI automatically, so clinicians no longer need to count any dots. The “Count the Dots” audiogram lives on in modern computer-based audiometry; as you will see in the examples below, it is underlaid behind the pure tone thresholds. The density of the dots at each frequency represents the relative importance of that frequency for speech intelligibility.

AudiologyOnline: Do you use the AI clinically?

Clayton Fisher: I use the AI every day when explaining a person’s pure tone audiogram, as it shows the effect of a person’s hearing loss on the audibility of average level speech sounds. This is more intuitive and understandable to patients than traditional degrees of hearing loss. I also like it because it is an objective measure of the percentage of audible speech information, and patients seem more accepting of a simple percentage that helps explain the hearing difficulties they are experiencing.

AudiologyOnline: Can you show me a clinical example?

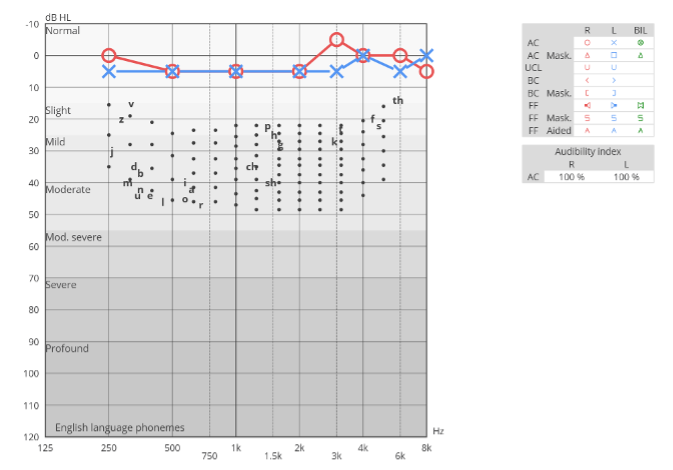

Clayton Fisher: In each audiogram, the speech information (i.e., dots) that falls below the pure tone thresholds is audible, while the speech information that falls above these thresholds is deemed inaudible.

For example, Fig. 1 illustrates a person with normal hearing thresholds where the individual’s AI is 100, indicating that the audibility of average speech is perfectly intact.

Fig. 1. Audiogram of Normal Hearing Thresholds. This audiogram displays an individual with normal hearing thresholds, where the AI is rated at 100, indicating that the audibility of average speech is fully intact.

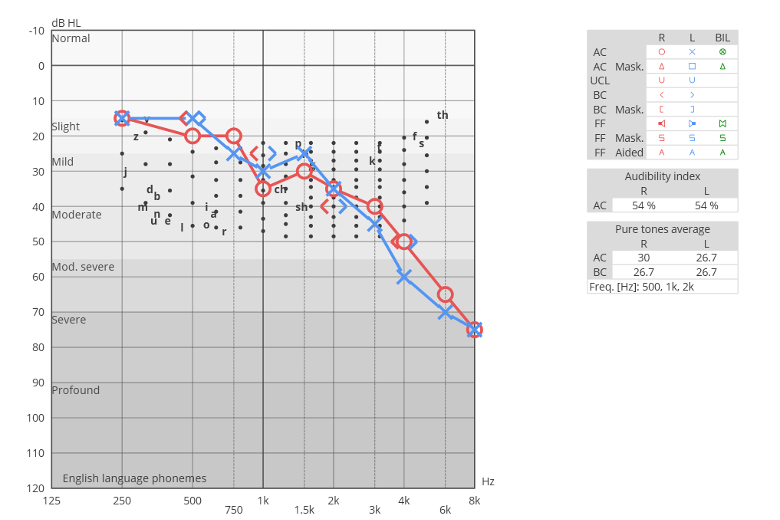

Conversely, Fig. 2 shows a case of a person with sloping hearing loss. This individual has an AI of 54 in each ear, which means that only 54% of average level speech is audible to them.

Fig. 2. Audiogram with Sloping Hearing Loss. Here, the AI is 54 in each ear, showing that only 54% of average-level speech is audible. This highlights the significant impact of sloping hearing loss on speech comprehension.

AudiologyOnline: How do patients react to learning their AI score?

Clayton Fisher: Patients often ask for a percentage when it comes to their hearing loss, don’t they? I believe that you can—and indeed, should—provide them with one. Percentages are familiar to patients, and thus learning their own AI score resonates deeply with them. Many are surprised to discover how limited their access to average speech is. As such, the AI facilitates a greater appreciation of the impact of their hearing loss. The AI's objective nature is crucial; the score is automatically calculated and presents an irrefutable fact, lending credibility even when the results are unexpected.

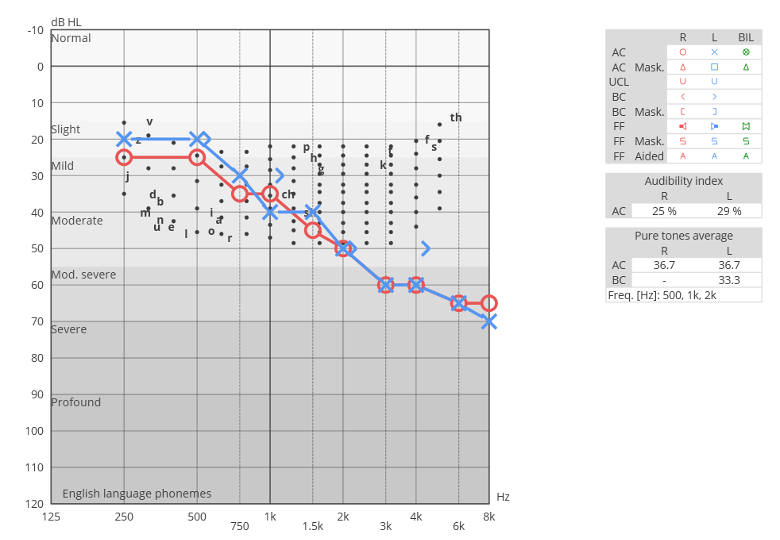

In the case illustrated by Fig. 3, the patient was surprised to learn that he hears less than 30% of average speech. This revelation was instrumental in helping him understand the reasons behind his frequent misunderstandings during conversations.

Fig. 3. Audiogram Highlighting Severe Speech Audibility Reduction. This patient discovered that only less than 30% of average speech is audible to him, illuminating the root cause of frequent misunderstandings in conversations.

AudiologyOnline: What might you say for the above example when you are counseling him on his audiogram?

Clayton Fisher: For a person with hearing loss that significantly limits audibility, as in the example above, I would say something simple: 'Mr. X, you have a significant hearing loss. This may surprise you, but you’re currently only hearing less than 30% of average-level speech.' I would then point to the AI numbers on the monitor screen here: specifically, 25% in your right ear and 29% in your left. 'It’s no wonder you must ask people to repeat themselves!' Then, of course, I would promptly demonstrate hearing aids to show him what it is like to hear more of what he should be hearing.

AudiologyOnline: Do you think it makes more sense to use the AI to describe a person’s hearing loss, rather than using the traditional “degrees” of hearing loss?

Clayton Fisher: I rarely speak to a patient in terms of the degree of their hearing loss anymore. Instead, I prefer to focus on how their hearing loss affects the audibility of speech.

For instance, to a clinician, describing hearing loss as 'moderate' indicates a significant condition, likely with an AI of less than 10%. However, to a patient, 'moderate' might imply something less severe, akin to walking at a 'moderate' pace or holding 'moderate' opinions.

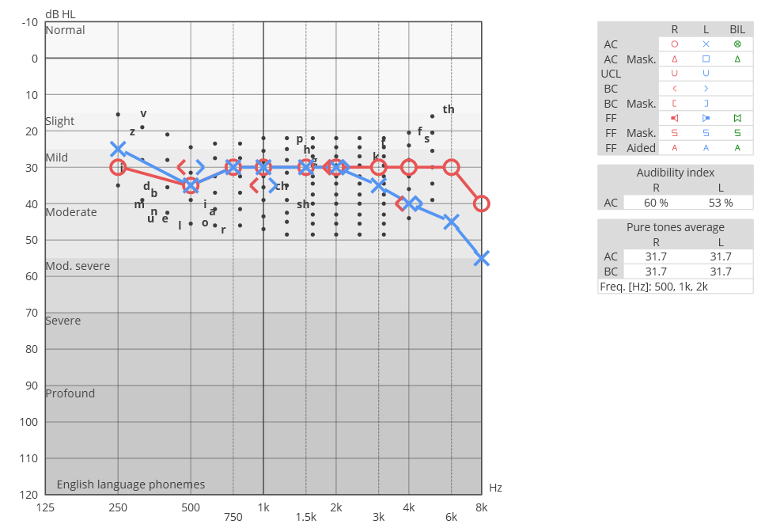

Similarly, a hearing loss that would be described as “mild” can, of course, have significant impacts on audibility, as seen in Fig. 4. This person’s right ear, which falls entirely within the “mild” range, has an AI of 60, which means it only provides their auditory cortex with 60% of speech when spoken at an average level.

These examples underscore why describing hearing loss in degrees can be misleading, potentially causing individuals to underestimate the severity of their condition.

Fig. 4. Audiogram Demonstrating 'Mild' Hearing Loss with Significant Speech Impact. This audiogram reveals a 'mild' hearing loss in the right ear, yet with an Audibility Index (AI) of 60, showing that only 60% of average-level speech is audible, highlighting the profound effect even 'mild' hearing loss can have on speech audibility.

AudiologyOnline: Can the AI be used to help determine who will benefit from amplification?

Clayton Fisher: I use the AI as a tool to help predict the potential benefit from amplification. Generally, the lower the AI score, the more likely someone is to experience a significant improvement with hearing instruments due to the drastic and noticeable change in audibility that amplification can provide.

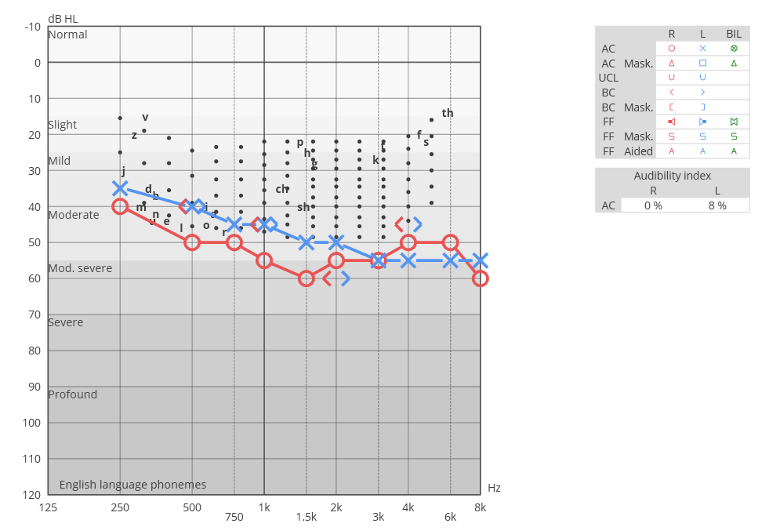

For instance, the individual depicted in Fig. 5 is likely to notice a substantial improvement with hearing instruments, as their audibility for average speech is 0% in the right ear and 8% in the left ear.

Fig. 5. Audiogram Indicating No Audibility in Right Ear and Minimal Audibility in Left Ear. This patient, with 0% audibility for average speech in the right ear and 8% in the left, stands to gain significant improvement from hearing instruments.

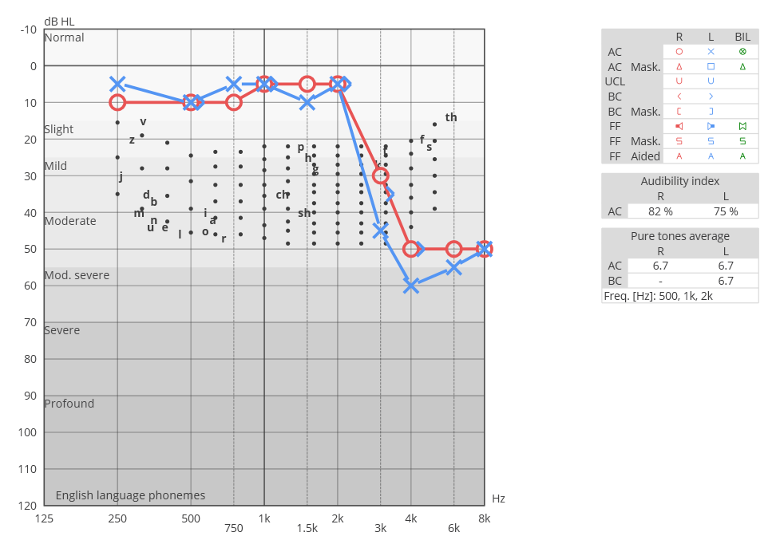

However, it's important to note that the AI should not be the sole audiometric criterion for determining hearing aid candidacy. As shown in Fig. 6, a person with relatively high AI scores (82% in the right and 75% in the left) can still be a clear candidate for hearing aids, based on audiometric criteria.

Fig. 6. Audiogram with High AI Scores Showing Hearing Aid Candidacy. Despite relatively high AI scores of 82% in the right ear and 75% in the left, this individual is considered a suitable candidate for hearing aids based on comprehensive audiometric evaluation.

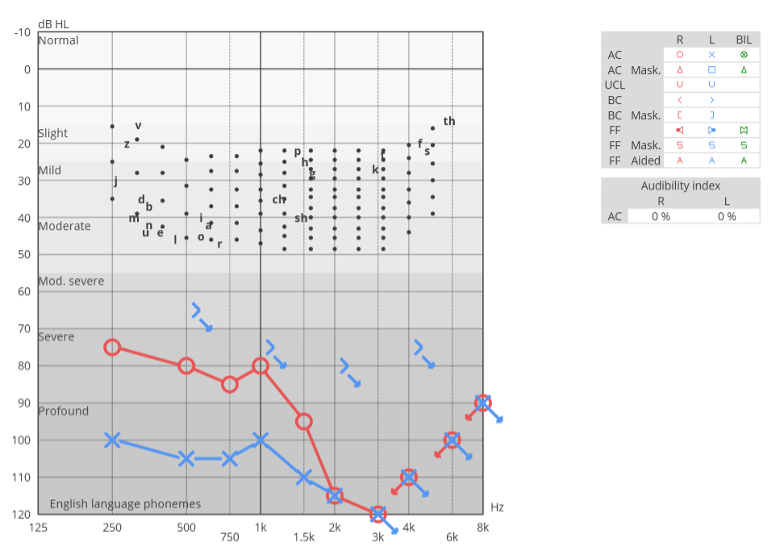

On the other hand, Fig. 7 illustrates an audiogram of an individual whose AI score is 0 in both ears and whose word understanding score is also 0%. This suggests that this person might be a better candidate for a cochlear implant than for hearing aids.

Fig. 7. Audiogram Demonstrating Zero Audibility and Word Understanding. With an AI score and word understanding score of 0% in both ears, this person is identified as a more appropriate candidate for cochlear implantation than for hearing aids.

AudiologyOnline: Is there a specific AI value that can be used as a cut-off criterion to determine when to make a strong recommendation for hearing aids?

Clayton Fisher: Before answering, it's important to note that a high Audibility Index (AI), such as in the 80s or 90s, does not automatically exclude someone from being a candidate for hearing aids.

Clinicians who are experienced in fitting hearing aids know that even people with normal hearing thresholds can benefit from hearing instruments if they have perceived hearing difficulties in noise. Similarly, experienced clinicians also know that many tinnitus sufferers who do not report hearing difficulty benefit from reduced perception of their tinnitus when using hearing instruments. For information on fitting low gain hearing aids check out my article on the subject.

That being said, audibility plays a crucial role in speech clarity. Therefore, in my practice with adults, I utilize a 70% AI cut-off value to determine when to strongly recommend hearing aids. An AI score of less than 70, based on an HL audiogram, serves as the threshold for recommending the use of hearing instruments due to the significant impact on audibility.

AudiologyOnline: Where does that 70% AI cut-off value comes from?

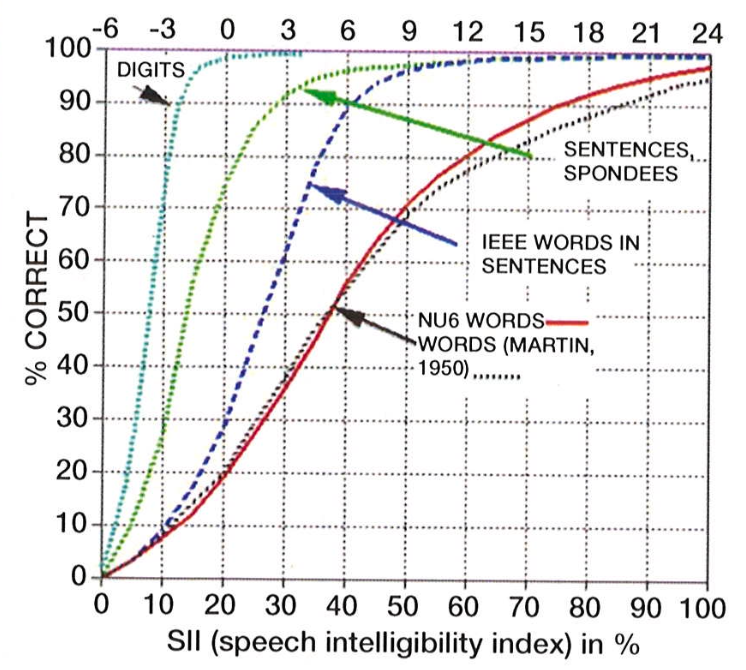

Clayton Fisher: Gus Mueller notes that, for hearing aid fittings, an aided Speech Intelligibility Index (SII) value of 70 is “Okay” - meaning, an AI/SII of 70 is associated with very high speech understanding, approximately 90%.

This relationship is demonstrated in the transfer functions illustrated in Fig.8, where an AI/SII of 70 is shown to enable a person to achieve close to 90% accuracy in speech intelligibility for words spoken in isolation. It's important to note that AI/SII values below this threshold tend to result in increasingly negative effects on speech understanding.

Fig. 8. Transfer Functions Demonstrating Speech Intelligibility. This figure illustrates how an AI/SII value of 70 corresponds to approximately 90% speech understanding accuracy for isolated words. It also highlights the decline in speech understanding with AI/SII values below 70, emphasizing the critical threshold for effective audibility and comprehension with hearing aids.

This figure was originally published in Killion and Mueller’s 2010 article: Twenty Years Later: A NEW Count-The-Dots Method and is used here with permission.

AudiologyOnline: How do I know when to say AI vs SII?

Clayton Fisher: It seems that the term AI is the norm when being used on the assessment side (based on the dB HL audiogram), whereas the term SII is what is used more on the treatment side (when we are looking at the real-ear aided response in dB SPL) for hearing aid fittings.

It's also important to understand that the AI, when calculated from the dB HL audiogram, is predicated on a speech level of 60 dB SPL. Conversely, SII measurements during hearing aid verification are typically conducted across multiple speech levels, such as soft (55 dB SPL), average (65 dB SPL), and loud (75 dB SPL) speech. This differentiation underscores the specific applications of AI and SII in assessing hearing loss and tailoring treatment strategies.

AudiologyOnline: Is the same AI/SII cut-off criterion for amplification used for children?

Clayton Fisher: Ryan McReery’s research group at Boystown has recently published recommendations for audibility-based hearing aid candidacy in children where they have found that a stricter cut-off criterion of an SII <80 is more appropriate for children.

The methodology to ascertain this value differs significantly for children, not relying solely on the HL audiogram. Due to the smaller size of children's ear canals, accurately predicting a child's true audibility necessitates measuring the real-ear-to-coupler difference and evaluating the child’s hearing thresholds in dB SPL. This involves using a real-ear measurement system to calculate the predicted unaided SII. If a child's predicted unaided SII for average speech is below 80, hearing instruments are recommended. This objective criterion is invaluable, providing clarity and consistency for clinicians when considering hearing aids for children with mild hearing losses.

AudiologyOnline: What do you want other clinicians to take away from this interview?

Clayton Fisher: With modern audiometers that now calculate the AI automatically, we have a powerful metric to quantify a person’s hearing loss at our fingertips. This is a single objective number that is ear specific and, because it is expressed as a percentage, is simple and understandable to patients.

References

Fisher, C. A. (2024). What is your protocol for fitting “low-gain” hearing instruments for slight and mild hearing losses (or for normal/near-normal hearing patients)? AudiologyOnline, Ask the Experts. https://www.audiologyonline.com

Hornsby, B. (2004). The Speech Intelligibility Index: What is it and what's it good for? The Hearing Journal, 57, 10-17.

Killion, M. C., Mueller, H. G., Pavlovic, C. V., & Humes, L. E. (1993). A is for audibility. Hear J, 46(4), 29-32.

Killion, M., & Mueller, H. (2010). Twenty years later: A NEW Count-The-Dots method. The Hearing Journal, 63(10), 12-14,16. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.HJ.0000366911.63043.16

Mealings, K., Valderrama, J. T., Mejia, J., Yeend, I., Beach, E. F., & Edwards, B. (2024). Hearing Aids Reduce Self-Perceived Difficulties in Noise for Listeners With Normal Audiograms. Ear Hear, 45(1), 151-163. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000001412

McCreery, R. W., Walker, E. A., Stiles, D. J., Spratford, M., Oleson, J. J., & Lewis, D. E. (2020). Audibility-based hearing aid fitting criteria for children with mild bilateral hearing loss. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 51(1), 55-67.

Mueller, H. G. (2018). Speech Mapping Puzzling Outcomes: What SII Should I Expect With a Good Match to Target? AudiologyOnline, Ask the Experts. https://www.audiologyonline.com

Suzuki, N., Shinden, S., Oishi, N., Ueno, M., Suzuki, D., Ogawa, K., & Ozawa, H. (2021). Effectiveness of hearing aids in treating patients with chronic tinnitus with average hearing levels of <30 dBHL and no inconvenience due to hearing loss. Acta Otolaryngol, 141(8), 773-779. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016489.2021.1957145

Resources for More Information

For more information about Inventis, visit https://www.inventis.it/en-na