As health care professionals, we have an obligation to educate our patients regarding their hearing loss and a proper plan of habilitation. To this end, we generally think of tangible assistive devices, such as hearing aids. Often we neglect to relay the importance of legislation enacted on behalf of our patients, which covers far more than technological advances. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), passed in 1990, encompasses a broad spectrum of considerations for people with disabilities, which includes those with hearing and vestibular disorders. However, the ADA does far more than help someone hear better on the telephone or make reasonable accommodations for someone with vertigo; it is about equality, accessibility, and opportunity. It is imperative to strengthen the connection in our minds between making a recommendation and helping someone have equal rights under the ADA. Our professional recommendations can bear much more weight and have a stronger impact when we are educated regarding the laws and have the knowledge to guide those with disabilities to appropriate resources. The goal of this paper is to discuss the foundation of the ADA, how it applies to our patients, and how it can be effectively utilized in our professional practices.

History of the Americans with Disabilities Act

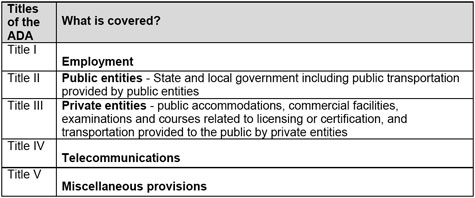

The ADA was signed into law on July 26, 1990 by President George H.W. Bush. While earlier disability legislation like the Smith-Fess Act of 1920, the Randolph-Sheppard Act of 1936, the Vocational Rehabilitation Amendments of 1943, 1954 and 1965, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Education for All Handicapped Children Act, later amended and renamed to the Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA) in 1990, attempted to provide equal rights and access, not one these pieces of legislation was as comprehensive as the ADA (Charmatz, 2000). The ADA gives federal civil rights protections to individuals with disabilities similar to those provided to individuals on the basis of race, color, sex, national origin, age, and religion. The law extends equal opportunity and civil rights protections for qualified individuals with disabilities in employment, in public and private sectors, public accommodations, transportation, state and local government services, and telecommunications. There are five titles within the ADA (Table 1).

Table 1. Five Titles of the ADA

ADA Terminology and Definitions

Individual with a disability: "A person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities" (ADA, 1991, n.p.)

Physical impairment: "Any physiological disorder or condition, cosmetic disfigurement, or anatomical loss affecting one or more of the following body systems: neurological, musculoskeletal, special sense organs, respiratory (including speech organs), cardiovascular, reproductive, digestive, genitor-urinary, hemic and lymphatic, skin and endocrine" (ADA, 1991, n.p.)

Substantially limits: "An individual must be unable to perform, or be significantly limited in the ability to perform, an activity compared to an average person in the general population" (ADA, 1991, n.p.)

Major life activities: "Activities that an average person can perform with little or no difficulty. Examples are: walking, speaking, hearing, breathing, performing manual tasks, seeing, learning, caring for oneself, working, lifting, sitting, standing and reading" (ADA, 1991, n.p.)

Reasonable accommodation: "A modification or adjustment to a job, the work environment, or the way things are usually done that enables a qualified individual with a disability to enjoy an equal employment opportunity" (ADA, 1991, n.p.)

Equal employment opportunity: "An opportunity to attain the same level of performance or to enjoy equal benefits and privileges of employment as are available to an average similarly-situated employee without a disability" (ADA, 1991, n.p.)

Essential functions: "The (employment) position exists to perform the function" (ADA, 1991, n.p.)

Qualified individual with a disability: "Satisfies the requisite skill, experience, education, and other job-related requirements of the employment position such individual holds or desires, and who, with or without reasonable accommodation, can perform the essential functions of such position" (ADA, 1991, n.p.)

Americans with Disabilities Act: Title I

Title I of the ADA focuses on issues of employment. The ADA & IT technical manual states that Title I "prohibits private employers, state and local governments, employment agencies and labor unions from discriminating against qualified individuals with disabilities in job application procedures, hiring, firing, advancement, compensation, job training, and other terms, conditions, and privileges of employment" (U.S. Department of Education (DOE), 2007, n.p.) The ADA covers employers with 15 or more employees, including state and local governments (U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), 1992). It also applies to employment agencies and to labor organizations. Title I covers all employees of state and local government regardless of the number of employees.

An individual (employee or applicant) who is able to perform the "essential functions" of a job with or without a reasonable accommodation is protected under Title I of the ADA (U.S. EEOC, 2007). A reasonable accommodation is an alteration made within the work environment and/or duties, procedures, or generally how things are done that result in an equal employment opportunity for an individual with a disability (DOE, 2007). An example of a reasonable accommodation for an individual with vertigo would be to provide an alternative to fluorescent lighting in their office or work space. An individual with tinnitus might request the use of a small radio to provide background noise as reasonable accommodation for his cubicle. A secretary with hearing loss might request an amplified telephone or use of a Captel (live captioned) telephone as a reasonable accommodation. Other examples of reasonable accommodations could include a modification to work schedules, duties, structure of job, or reassignment to a vacant position (Job Accommodation Network (JAN), 2007).

An employer is required to provide an accommodation for a known (or assumed) disability unless the accommodation presents an "undue hardship" for the employer's business (ADA, 1991; D'Angelo v. ConAgra Foods Inc., 2005). The U.S. EEOC defines undue hardship as "an action requiring significant difficulty or expense when considered in light of factors such as an employer's size, financial resources, and the nature and structure of its operation" (2007, n.p.). An employer must analyze the situation to determine whether or not it would cause an undue hardship. It is helpful if the qualified individual is informed about their disability and possible accommodation needs. An employer is not required to make an accommodation that would require compromising production or quality standards (ADA, 1991). An employer is not required to cover personal assistance devices such as canes, wheelchairs, prosthetic limbs, hearing aids, glasses and similar devices if they are necessary on and off the job (U.S. EEOC, 2007).

How is a disability disclosed? An individual may disclose a disability verbally or in writing, as well as ask for a modification in the same manner. A medical professional may ask for a reasonable accommodation for a patient. It is recommended, but not required, that the request be made in writing. An employer may ask for medical documentation or records in order to determine whether or not the disability aligns with the ADA definition of disability. In addition, the employer may ask what type of accommodation is needed. However, an employer may not inquire about the severity of the disability, existence of a disability if not disclosed, or nature of the disability (ADA, 1991).

An example of how Title I applies to employment can be found in the civil rights court case of D'Angelo v. ConAgra Foods Inc. (2005). In this case an employee who was diagnosed with vertigo requested a reasonable accommodation in a fish processing plant. The employer requested a letter confirming the diagnosis and then denied the employee's request to be removed from working on a conveyor belt. Ms. D'Angelo was terminated by her employer who found her unable to work at the plant due to her disability. The U. S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit ruled that Ms. D'Angelo did not have a disability under the ADA because the vertigo (and her difficulty watching items on a conveyor belt) did not substantially limit any major life activity (2005). However, they did find that her supervisor and ConAgra Foods Inc. did regard her as having a disability of vertigo. Thus, her employer was responsible for providing a reasonable accommodation under the ADA. The court's final ruling was that Ms. D'Angelo was covered under the ADA as a person who was regarded as having a disability.

Americans with Disabilities Act: Title II

Title II of the ADA focuses on public entities. It ensures that a qualified individual with a disability will not be denied the benefits of, excluded from participation in, or subjected to discrimination under any program, services, or activity conducted by State or local government entities (U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), 1993a). Title II includes transportation provided by public entities (U.S. Department of Transportation, 2007). Title II does not apply to the Federal Government. Instead, the Federal Government is covered by sections 501 and 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973.

Public programs may not refuse to allow an individual with a disability from participating in any programs, services, or activities. They must provide the most integrated setting possible, taking into consideration the accessibility of the facility and the availability of auxiliary aids and services. In addition, materials and information must be available in alternative formats and formats useable by people with auditory and visual impairments (Gostin, 1993). Equally effective communication for people with disabilities is required by the ADA and can be provided by the use of auxiliary aids which include, but are not limited to: note takers, interpreters, transcription services, written materials, amplified telephone receivers, assistive listening devices and systems, hearing-aid-compatible telephones, closed caption decoders, open and closed captioning, TTY/TDD and videotext displays" (Gostin, 1993).

An example of how Title II applies to state and local government entities can be found in the civil rights court case of Armstrong v. Wilson (1997). This was a class action case arguing that state correctional facilities are covered under Title II of the ADA. The case charged that facilities, services, and benefits within California State correctional facilities needed to be accessible to individuals with disabilities. The Plaintiff group was comprised of past, present, and future inmate and parolees with mobility, sight, hearing, learning, or kidney disabilities. They alleged that the California State correctional system had violated Title II of the ADA by denying them access to programs offered within the prison (Armstrong v. Wilson, 1997). In addition, the State Correctional system failed to provide reasonable accommodations and auxiliary aids needed for effective communication (Armstrong v. Wilson, 1997). The conclusion of the case found that the Defendant violated Title II of the ADA.

Americans with Disabilities Act: Title III

Title III of the ADA focuses on private entities. The essence of Title III is that people with disabilities should have equal choice of retail goods and services providers. A vast number of places to which Title III applies are places that people choose to attend spontaneously. In turn, it is important for these entities to provide accessible services, which includes providing auxiliary aids (U.S. DOJ, 1993b; U.S. DOJ, 2007). Title III covers public accommodations and commercial facilities. Title III also covers private entities that provide transportation to the public. It prohibits discrimination in private entities that are open to the public.

Some examples of private entities covered under Title III:

- Hospitals and doctor's offices

- Restaurants

- Theaters

- Parks not operated by the government

- Grocery stores

- Retail stores an shopping centers

- Hotels

Americans with Disabilities Act: Title IV

Title IV of the ADA covers the broad area of telecommunications. The Telecommunications Accessibility Enhancement Act (TAEA) of 1988, required the federal government to provide TTY/TDD relay services, was passed prior to the 1990 legislation of the ADA (Charmatz, 2000). Title IV of the ADA went into effect in 1993 and dramatically expanded relay system coverage between states and within states (Charmatz, 2000; Harrison, 1992). The law mandated that telephone companies provide more comparable coverage. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) requires relay services to function in a manner equivalent to conventional telephone services (Charmatz, 2000).

Although improvements have been made to TTY and relay communication systems, people who are hard of hearing report that they do not use TTY or TDD, but rather a standard telephone or cellular phone. These individuals continue to report, however, that they still experience significant difficulty communicating through the use of a telephone. The Telecommunications for the Disabled Act of 1982, the Hearing Aid Compatibility Act of 1988, and the Telecommunications Act of 1996 worked toward making telephones more accessible to people who have hearing loss and use hearing aids (Gostin, 1993). In 2003, the FCC addressed longstanding concerns about wireless technology and modified the Hearing Aid Compatibility Act of 1988 to include wireless cellular phones (FCC, 2003). The last FCC Deployment Benchmark to be implemented mandated that at least fifty percent of all digital wireless cellular phone or handsets offered by manufacturers meet a U3/M3 standard by February 18, 2008 (FCC, 2003; FCC, 2007).

Also covered under the ADA Title IV Telecommunications umbrella is closed-captioned television. Initially, closed captioning was provided for federal or federally-funded television programming (Harrison, 1992). However, in 1990 Congress passed the Television Decoder Circuitry Act (TDCA), which required all televisions in the United States produced or imported after July 1993 with screens thirteen inches or larger, be capable of displaying closed captioned television transmissions without the assistance of external equipment (Charmatz, 2000). In 1996, the Telecommunications Act was passed to expand closed captioning to cable television channels (Charmatz, 2000). A few years later, the FCC required that all captioning be integrated into new non-exempt programming within an eight-year time period beginning January 1, 1998 (Charmatz, 2000). As new television technology continues to be released, it will be necessary to modify current regulations.

Americans with Disabilities Act: Title V

Title V of the ADA covers both miscellaneous provisions and technical provisions. Some of the information covered in Title V relates to the following topics: construction, State immunity, prohibition against retaliation and coercion, architectural barriers, attorney's fees, technical assistance, Federal Wilderness Areas, coverage of Congress and the Legislative Branch, illegal use of drugs, general definitions, Amendments to the Rehabilitation Act, alternative means of dispute resolution, and severability (Harrison, 1992). Title V also covers information specific to ADA as it relates to other laws. For example, the ADA does not cancel anything in Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (ADA, 1991). Title V clarifies that both States and Congress are covered by the ADA (ADA, 1991). It prohibits any state agency from claiming immunity from ADA related legal action.

Any additional State or Federal laws addressing individuals with disabilities may be executed under the umbrella of the ADA (Harrison, 1992). This way if law is developed that is more stringent than what is currently outlined in the ADA, the new law may be adopted into the existing ADA legislation to provide the maximum protection for individuals with disabilities.

Conclusion

Although the ADA is a broad law and can be somewhat confusing when determining a patient's coverage, it is our responsibility as hearing health-care providers to be knowledgeable of the law and advocate for people with disabilities. It is important to remember that the interpretation of the ADA as it relates to the coverage of individuals is determined by the courts and thus, is in a state of constant revision.

Tips

- To access further information about reasonable accommodations and the ADA, visit the Job Accommodation Network (JAN) website section titled "Reasonable Accommodation and the ADA Process" at: www.jan.wvu.edu/media/raproc.html

- A list of frequently asked questions is available on the JAN web site to help providers navigate and identify potential reasonable accommodations, including assistive device for various disabilities: www.jan.wvu.edu/media/Hearing.html . For general ideas, visit www.jan.wvu.edu/soar/disabilities.html

- If you plan to write a letter to an employer or to an entity covered under the ADA, remember the following procedures: identify the person with the disability, state that an accommodation is requested under the Americans with Disabilities Act, identify the specific tasks that are presenting difficulty, list accommodation ideas, request accommodation ideas, request a response in a reasonable amount of time, provide medical documentation or state that it will be presented upon request, and consider sending copies of the letter to other appropriate parties.

- A form made available on the JAN web site that can be used in response to an employer's request for further documentation of a disability when a reasonable accommodation request has been submitted can be found at: www.jan.wvu.edu/media/medical.doc

- Contact your regional Disability and Business Technical Assistance Center (DBTAC) to request free brochures on the ADA at: www.dbtac.vcu.edu/

ADA & IT Technical Assistance Centers

Disability and Business Technical Assistance Centers (DBTACs)

1-800-949-4232 (V/TTY)

Find your local/nearest site determined by region

www.dbtac.vcu.edu/

American Association of People with Disabilities (AAPD)

1629 K Street NW, Suite 503

Washington, DC 20006

202-457-0046 (V/TTY)

800-840-8844 (Toll Free V/TTY)

www.aapd.com

Federal Communications Commission (FCC)

Consumer & Governmental Affairs Bureau

445 12th Street, SW

Washington, DC 20554

1-888-CALL-FCC (1-888-225-5322) voice

1-888-TELL-FCC (1-888-835-5322) TTY

Email: [email protected]

www.fcc.gov/cgb

Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

www.fda.gov/cellphones/index.html

Job Accommodation Network (JAN)

800-526-7234 (V)

877-781-9403 (TTY)

www.jan.wvu.edu

Searchable Online Accommodation Resource (SOAR), a division of JAN

www.jan.wvu.edu/soar/index.htm

National Center on Workforce & Disability

National Center on Workforce and Disability/Adult

Institute for Community Inclusion

UMass Boston

100 Morrissey Blvd.

Boston, MA 02125

1-888-886-9898 (voice/TTY)

www.onestops.info/article.php?article_id=49

National Organization on Disability (NOD)

910 Sixteenth Street N.W.

Suite 600

Washington, DC 20006

Phone: (202) 293-5960

TTY: (202) 293-5968

Email: [email protected]

www.nod.org

U.S. Department of Justice

Americans with Disabilities Act Disability Rights Section

U.S. Department of Justice

950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW

Civil Rights Division

Disability Rights Section - NYA

Washington, D.C. 20530

1-800-514-0301 (voice)

1-800-514-0383 (TTY)

www.usdoj.gov/crt/ada/adahom1.htm

References

Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990, Pub. L. No. 101-336, § 2, 104 Stat. 328 (1991).

Armstrong v. Wilson, 24 F.3d 1019 (9 th Cir. 1997).

Ball v. AMC Entertainment, Inc., 315 F. Supp. 2d 120 (D.D.C. 2004).

Charmatz, M., Geer, S., Vargas, M., Brick, K. & Strauss, K. P. (2000) Legal Rights, The Guide for Deaf and Hard of Hearing People (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press.

D'Angelo v. ConAgra Foods Inc, 422 F.3d 1220 (11th Cir. 2005)

Federal Communications Commission (2003). Public Notice, Washington, D.C. 20554. Retrieved March 17, 2007, from www.fcc.gov

Federal Communications Commission. (2007). Consumer Fact Sheet Washington, D.C. 20554. Retrieved March 17, 2007, from www.fcc.gov/cgb/consumerfacts/hac.html

Gostin, L. O., & Beyer, H. A. (1993). Implementing the Americans with Disabilities Act, Rights and Responsibilities of All Americans. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Harrison, M., & Gilbert, S. (1992). The Americans with Disabilities Act Handbook. Beverly Hills: Excellent Books.

Job Accommodation Network (JAN), U.S. Department of Labor. (2007). Office of Disability Employment Policy. Retrieved March 17, 2007, from www.jan.wvu.edu/

U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (1992). Technical Assistance Manual on the Employment Provisions (Title I) of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (2007). Disability Discrimination. Retrieved April 3, 2007 from www.eeoc.gov/types/ada.html

U.S. Department of Justice. (1993a). The Americans with Disabilities Act - Title II Technical Assistance Manual. Retrieved April 18, 2007, from www.usdoj.gov/crt/ada/taman2.html

U.S. Department of Justice. (1993b). The Americans with Disabilities Act - Title III Technical Assistance Manual. Retrieved April 18, 2007, from www.usdoj.gov/crt/ada/taman3.html

U.S. Department of Justice. (2007). Information and Technical Assistance on the Americans with Disabilities Act. Retrieved April 18, 2007, from www.usdoj.gov/crt/ada/adahom1.htm

U.S. Department of Transportation - Federal Transit Union. (n.d.). Americans with Disabilities Act - Full Regulatory History. Retrieved April 3, 2007, from www.fta.dot.gov/civilrights/ada/civil_rights_3904.html