Learning Outcomes

After this course learners will be able to:

- Identify four key terms important in a discussion of ethical conduct.

- List three examples of ethical risks or dilemmas in clinical practice.

- Define what is meant by "conflict of interest."

Introduction

One of the topics and concepts that we will be focusing on throughout this course is conflict of interest. It is an essential phrase when you discuss ethics, and you will be able to define it by the end of this course. I want to make sure we cover the entire breadth of the topic. It is a broad approach to an ethical discussion. Some of you have already listened to ethics courses or lectures, and very often, they focus on one specific aspect of ethics in audiology. For example, the most common would be ethics in audiological practice. I recognize that many have signed up for this webinar from a variety settings (e.g., university settings, clinics, research). I wanted to cover the broad theme of ethics in audiology, rather than focusing on any one particular topic. We will start with an introduction that will provide you with some background on my perspective and experience on ethics.

My First Professional Ethical Question

I have had an incredible career in audiology, over 40 years, and still counting. I have no intention of slowing down anytime soon. Within the first month of taking my first job as a speech pathologist at Baylor College of Medicine, I ran into an ethical issue, and I was not prepared for it. I had a master's degree in speech pathology, but not once did we ever discuss ethics. You did not hear much about ethics back in those days. We did not have guidelines as we do today.

I had a young preschool child who had a language and articulation delay as my patient. I agreed to provide clinical services to this child as a speech pathologist, and within weeks, he had overcome this articulation problem. The parents were so excited, and they brought me a gift certificate. The gift certificate was to a sports store that had camping equipment. My wife and our first child were going to go camping, and I had mentioned that to the parents at one point. It was a tremendous amount of money for the time, something like $50. At that time, our rent for our duplex was only $110, so you can see it was a large amount of money. I did not know what to do. I wanted to take the gift certificate, but I realized this might be inappropriate.

When we get into principles later in the course, I want to mention that whenever you have a concern at all about ethics, you always want to seek someone's advice. Go to your superior. As a young audiologist, I went to my mentor, James Jerger. I said, should I accept this gift? He advised me to contact the lawyers, the legal department to see what they say. I was no longer providing services to this patient, and they allowed me to keep it. As I was preparing this webinar, I thought of another aspect that was also representing an ethical question. That is if you are about to provide services to someone where the problem is perhaps very temporary and transient, should you even agree to provide the services? Or should you withhold the services until you see whether or not the problem corrects itself? With this child, it's possible that within perhaps another month or two, this developmental articulation problem would have fixed itself. We will get into those kinds of discussions later.

Ethics Evolution in The American Academy of Audiology

As time went on, I became more active in the profession. I became an audiologist and then was part of the founding of the American Academy of Audiology. Ethics took a much more critical role in my career. At the very beginning of AAA back in the late 80s and early 90s, we had to wrestle with this issue. Now we are not just talking about an individual's ethical decisions and dilemmas; we are talking about an entire profession. Considering how the profession should address things such as financial support for the convention from manufacturers. The demands from manufacturers such as giving them proper credit. For example, naming a party or big event for a specific manufacturer. We had to wrestle with these as I was on the Board of Directors for the AAA. I remember through these years; we had many debates and discussions. Ethics became much more critical in my mind at that point. At that time, the American Academy of Audiology began to develop its first ethical practice guidelines, and we will talk much more about those. We also developed a Scope of Practice and other documents that now guide our audiological practice.

Over the years, I've had to deal with this topic of ethics from many perspectives, and that is what I am sharing with you today. As an individual clinical provider and running a clinical practice in a busy medical center, I've had to deal with ethics on a day to day basis. Also, as the director of audiology for over 30 years, I had ensure we all were following a professional approach to audiology, consistent with ethical guidelines within our Scope of Practice. As time went on, I ended up becoming a chair of a department at the University of Florida. At that point, I dealt with even higher levels of ethical issues. Now I had an entire department with both speech pathologists and audiologists. I've dealt with ethical concerns and issues over the years, and it's that perspective that will guide this presentation. Any audiologist and student will encounter ethical questions sooner or later.

General Guidelines, Principles & Terminology

Now, I'm going to review the principles and terminology. I'm going to review quite a few terms and also some fundamental principles. If you follow these principles and adhere to them very carefully, you are most likely be conducting yourself ethically in most situations. As a general rule, the tough part about ethics is not knowing what to do once you've identified that something is unethical. It's making that decision, is this behavior or are activities falling into the category of appropriate professional activities, or might they be construed as unethical? Once you've made that decision, the rest is easy; you will know exactly what to do. Let's cover some basic principles and basic terminology.

- Adhere to the Code of Ethics for Audiology (e.g., AAA)

- Comply with Audiology Scope of Practice

- Follow HIPAA (Health Information Portability and Accountability Act)

- Follow FERPA (Federal Education Rights and Privacy Act)

- Practice according to ethical guidelines for your state

- Appreciate differences between ethics vs. law

- Remember: "The right thing to do is to do what is right."

- Follow the "golden rule" in professional life

- Adhere to the adage: "Integrity is doing the right thing, even if nobody is watching."

- Would you tell your parents or patients about what you are doing?

- When in doubt … reach out!

First, you must adhere to professional codes of ethics, and in our case, we have both the AAA and ASHA codes. I'm not familiar with the ASHA Code of Ethics, but I'm very familiar with the AAA Code of Ethics. Scope of Practice was first developed by a task force led by Robert Keith. Our Scope of Practice was written quite well. It included such practices as distributor assessment and management, interpretive monitoring, auditory processing disorders, management, all the things that we could be doing. If what you want to do in audiology is not defined in the Scope of Practice, then you should not do it. A good example, we're not legally permitted to dispense medication. Even though we may see a lot of children who are receiving sedation or anesthesia for an ABR, for example, we can not administer that sedation. That'd be a severe ethical lapse.

Another set of guidelines for ethical practice is what's referred to as the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). It has to do with patient confidentiality, the security of patient data, and the patient's privacy. HIPAA covers our clinical interactions with patients, but there's a parallel set of guidelines for students. If you are in an academic setting or even if you are a supervisor or preceptor for students, you need to be familiar with the Federal Education Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA).

There are also ethical guidelines at the state level in the United States. For example, if you get on to the licensure board website for your state, you will find ethical guidelines. Or you might find regulation or administrative regulations guiding audiology that will mention ethical guidelines. You need to be familiar with those wherever you might be practicing. We're going to cover the distinction between ethics and law. That's not always very clear cut, but we are going to talk about that a little later.

"The right thing to do is to do what is right." It sounds a little too simple, but it's true. If you are not doing the right thing in your mind, you are probably violating some ethical guidelines. Another is the golden rule in professional life. In other words, do unto others, whether they're patients, colleagues, or anyone you interact with. That's a simple guideline that will help you tremendously in maintaining ethical practice. Another is the adage, "Integrity is doing the right thing even if nobody is watching." You are not only following ethical practice because you might get in trouble if somebody finds out, but you also want to do it even if nobody is ever going to know about it. Then another guideline is, would you tell your parents, patients, colleagues, or administrative superiors what you were doing?

When in Doubt?

The first thing you need to do is document your concerns because the issue may resurface later. You want to have some way of refreshing your memory on what the details of this issue were. This is particularly important from a legal point of view to maintain documents to prove that you had some concerns, and took the right steps to resolve this ethical dilemma. Immediately inform your administrative superior. I can not emphasize this enough. You are distributing or sharing the responsibility for the decision that you are about to make. You are not making it all by yourself. Sometimes the most appropriate higher level to go to is human resources, mainly when it involves some behavior on the part of an employee that you are responsible for. You may feel the need to go straight to legal counsel because they are the ethics experts. Also, many of these issues are potential legal issues, and this falls within their domain. That is ultimately your safest alternative, and if you are in private practice, you want to have an attorney that you can turn to that represents healthcare professionals.

Key Terminology

We will cover some of these terms in-depth later during this course, but I wanted to review them here. Appearance is what you are doing or appear to be doing. Bias, we all have biases, sometimes they're unconscious, but we shouldn't knowingly have a bias in our dealings with patients, colleagues, or anyone else in our practice. Now, the next word has an unusual spelling, it's casuistry, and can be pronounced different ways. Casuistry means deception or doing something to make it look like things are proper, but they're not. Coercion is trying to get somebody to do something that you want them to do that they really shouldn't do. Usually, it involves some threat. Conflict of interest, we will talk about this quite a bit. We're going to talk about ethics versus the law. Fraud, that's another key term. Fraud is a widespread ethical problem in every health profession, and we will define how it can be committed. Sometimes you can commit fraud without even realizing it. Incentive, you want to have good incentives, not nefarious or poor incentives. Informed consent, we will talk more about that. You don't want to misrepresent yourself in any way. Morality has a lot to do with ethics. Negligence is important; sometimes, you do not even realize that you are doing something unethical. Negligence is almost always going to lead to problems. Reprimand is what usually happens initially when you are violating some ethical guidelines. Your superior first reprimands you, then perhaps a sanction. Standard of care, another fundamental term, so I will define that in more detail in a moment. Veracity means being truthful, totally straightforward, and honest. A virtue is something that we strive to be. Virtue is doing the right thing at all times.

- Appearance

- Bias

- Casuistry

- Coerce

- Conflict of Interest (COI)

- Ethics versus Law

- Fraud

- Incentive

- Informed Consent

- Misrepresent

- Moral

- Negligence

- Professional Liability

- Professionalism

- Protected Health Information (PHI)

- Reprimand

- Sanction

- Standard of Care

- Veracity

- Violation

- Virtue

Conflict of interest. "A conflict of interest or appearance of a conflict of interest exists when a person or entity in a position of trust has a financial or personal interest that could unduly influence or could appear to influence, decisions related to a primary interest such as patient care, student education or validity of research" (AAA, 2017). A conflict of interest or an appearance of a conflict of interest, that's very important. You may not have a direct conflict of interest, but it might look like it to an outside person, maybe to a patient. When a person or an entity in a position of trust has a financial or a personal interest that could unduly influence or at least appear to influence your decisions regarding patient care, student education, or the validity of the research. Conflicts of interest are often not black and white. They are not clear cut, and you want to be conservative. If you think there might be a conflict of interest or even the appearance of it, you want to take the proper steps to avoid that.

Examples of conflict of interest. If you are in clinical practice, the conflicts of interest often involve compensation of some type, whether that is financial compensation from an industry that's related to audiology such as the hearing aid industry or diagnostic equipment. Or a financial interest in an entity that refers patients to you or that you refer patients to. This is a prevalent issue in clinical practice. For example, you are serving as a consultant for a manufacturer that also supplies equipment to your clinic. In university teaching, you can not requirie a textbook you authored for a course unless you give the students a choice to use another textbook. Or you assure them that you are not benefiting financially from their purchase of that textbook. Another conflict of interest is teaching responsibilities at a competing institution, at the very least, you must disclose that.

There are also conflicts of interest in professional leadership. Any leader in the profession has to read and sign conflicts of interest forms. Right now, I am serving as the Chair of the Board of Directors of the ACAE. The ACAE is the accrediting entity affiliated with AAA. Every year I have to sign a conflict of interest form, which says the information that we discuss at our board meetings is confidential. Also, I'm not going to be influenced or swayed by any outside entities such as the manufacturer. These are legal documents, so you need to follow the requirements that you've agreed to with your signature.

- Clinical Audiology Practice

- Financial compensation from related industry

- Financial interest in referral (to/from) entity

- Financial ties to companies that are vendors for clinic

- University Teaching

- Use of required authored textbook in courses

- Teaching responsibilities at a competing institution

- Professional Leadership

- Undisclosed financial interest in related industry

- Undisclosed leadership position in another organization

- Advisory board of company related to audiology

Professional liability. If you practice as an audiologist, you've immediately accepted professional liability. You don't have to sign any documents. You are automatically liable for any injury that is caused intentionally or unintentionally to your patients. Like the Hippocratic Oath, where we want to help our patients. We don't want to hurt our patients because we have advanced knowledge of audiology, advanced training, and skills. We have a responsibility to follow specific standards of conduct and try to protect our patients from unreasonable risks.

Professionalism. This is acting out the values and beliefs of people who are helping others who entrust their care to others, including us audiologists. We're always putting our patients' interests first. That's professionalism, and it's a fundamental principle of ethical behavior.

Informed consent. Another term I want you to remember is informed consent. Now there are several types of informed consent. There is informed consent involving clinical services. If you are in any major institution, a hospital, university medical center, or clinic, every patient should sign a consent form agreeing to be evaluated. The informed consent also states they agree to any management that you recommend for them. If the patient is a minor, the parent or a legal guardian will sign the consent.

Fraud. This is an act, expression, omission or concealment which is either actual or constructive to deceive others. When you think of fraud, you think of deception, and the most common claim is if you are billing for a service that you did not provide. You are charging a patient for something that they never received. This is always unethical, especially when billing for services that are paid for by the federal government (e.g., Medicare, Medicaid). This can happen almost unintentionally. For example, you may have a billing sheet that you check off four or five procedures that were performed. Perhaps you, a student or front desk staff inadvertently check off that service that the patient did not receive. If that happens, that is fraud, even if it is negligent and unintentional.

Protected health information. This is part of HIPAA and is any information that will allow you to identify who that patient is (e.g., name, geographical identifier, dates, email address, phone number, social security number).

Standard of Care. Another critical term is the standard of care. Standard of care is what every audiologist should do when providing service to the patient. It is using caution when taking care of patients. It's being adequately qualified to perform the services and not delivering services that they're not qualified to do, even if it might be within the Scope of Practice. The best way to understand the standard of care is to know that you are practicing audiology according to the clinical guidelines.

Ethics vs. Law

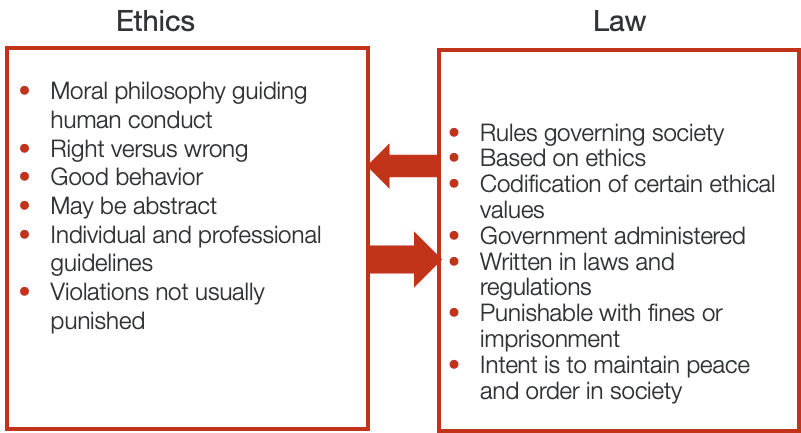

There is a distinction between ethics and the law. You can be unethical in your behavior and not be committing a crime, and there is certainly a connection. Our professional guidelines for how we should behave may or may not be defined in the laws where we're practicing. Whereas laws are very clear cut and very easily definable guidelines that we must follow.

Figure 1. Difference between ethics vs. law

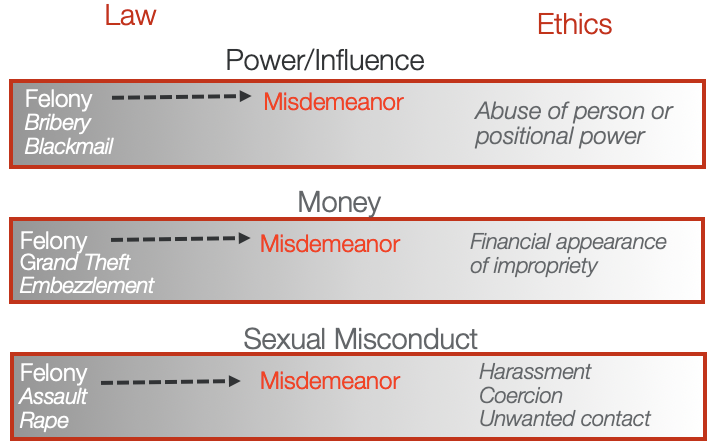

A good example is if you are caught speeding, and you get a speeding ticket from a police officer. You have broken the law, but there is nothing unethical about speeding because that is not relevant to your professional conduct. The distinction between law and ethics can be fuzzy. It's a gray area and not clear cut. Figure 2 shows a few examples of ethical issues that are also legal issues.

Figure 2. Legal versus ethical issues

Criminal vs. Civil Law (and Lawsuits)

There are two types of law. Civil cases are usually the cases that audiologists will be involved in when there is a professional liability issue. This might be a situation where someone says we did something we shouldn't have done. Whereas crimes are usually offenses against the state. Sometimes unethical behavior can also be a crime.

Guidelines for Ethical Conduct

If you had to read one document aside from the American Academy Code of Ethics and Scope of Practice, I recommend Ethics in Audiology. Those are also vital documents; you should read and have them handy. The State Licensure Board also has references to ethics. If you are in a large setting like a university or hospital, there are also separate regulations, policies, and procedures that might differ from what we have professionally with AAA or at the state level.

AAA Code of Ethics

This covers all of the major principles that I've already discussed. One thing you want to do after this course is to go back and read it if it has been a while. Download it as a PDF file and keep it on your computer. If you have people working with you, I would print it out and make sure everybody reads it. Then discuss it and ensure that you are practicing audiology within these guidelines.

Ethics in Audiology Education

Federal Education Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA)

FERPA is the most crucial guideline for ethics in audiology education for the professor, instructor, or preceptor. If you are in an academic setting, you will need to show that you are familiar with FERPA guidelines and that you understand how to follow them in your role in the academic setting. Just like HIPAA, FERPA classifies protected information for students into three categories: educational information, personally identifiable information, and directory information. Most of the time, directory information is not covered under FERPA, particularly if the students' names can appear in a directory.

Many unintentional FERPA violations can occur, such as:

- Overheard conversations about students

- Discarding student records improperly, e.g., without shredding

- Release of information to parent of student > 18 years

- Vendor misuse of student educational records

Other Key Terms in Audiology Education

Plagiarism. This is taking another's intellectual property and making them your own. Some tools can combat plagiarism. Turnitin is an online program, and we tell our students in advance we're going to be looking at what they're submitting. It is almost impossible to document plagiarism unless you are using some online software.

Conflicts of interest in education. We discussed this previously.

Falsifying CV. An example of falsifying or padding a resume is stating incorrect information to your prospects.

Failure to acknowledge academic contributions. In other words, somebody contributed to your work, maybe even wrote part of the paper that you've written or collected some of the data, but you did not acknowledge that they contributed.

Sexual harassment. Unfortunately, we hear a lot about this type of misconduct in the news — sexual harassment or otherwise creating a hostile or uncomfortable work or educational environment.

Violating fairness and discrimination policies. Or treating one student a little differently than another because you like one student more than the other, that is unethical.

Failure to report unethical conduct. This is a critical point. There are apparent guidelines in FERPA about what you should report. If you are not part of a solution, you are part of a problem.

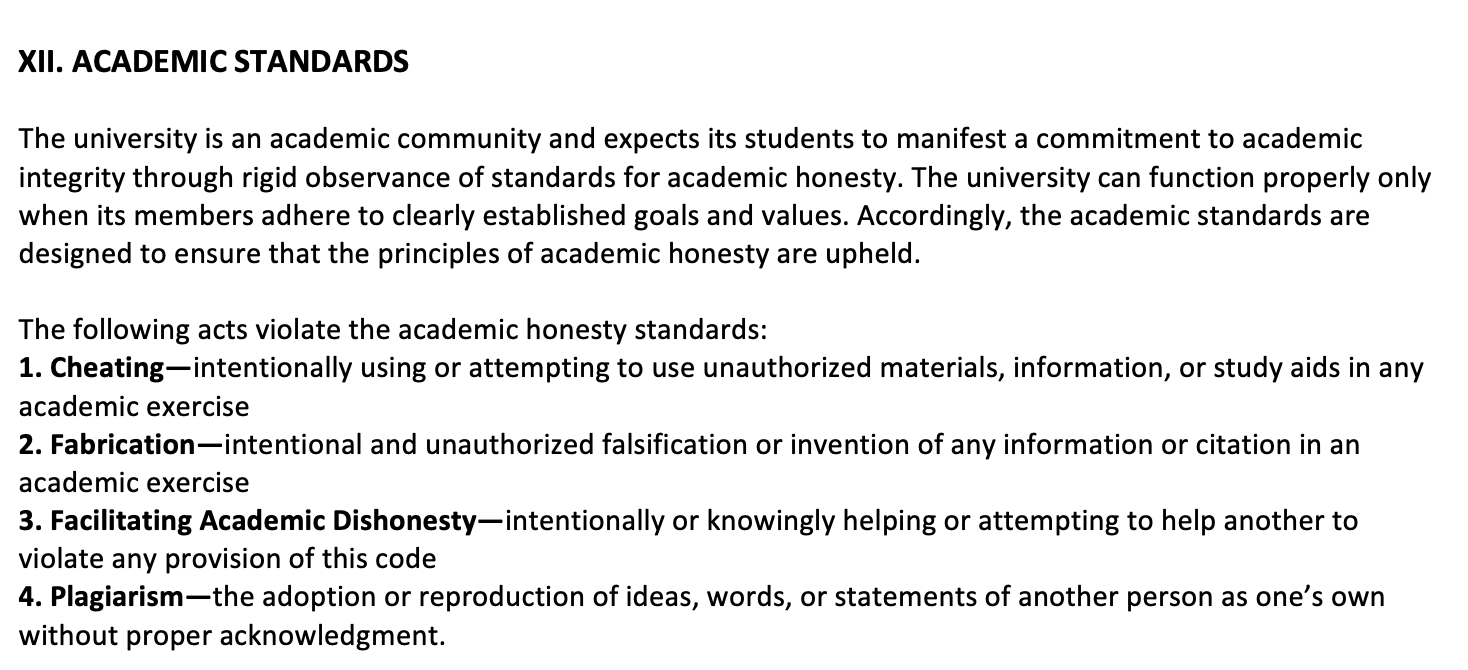

Figure 3 shows examples of how we integrate ethics into the academic setting. You can see it addresses cheating, fabrication, facilitating academic dishonesty, and plagiarism.

Figure 3. Example of ethics in an academic setting. Statements from AuD course syllabi.

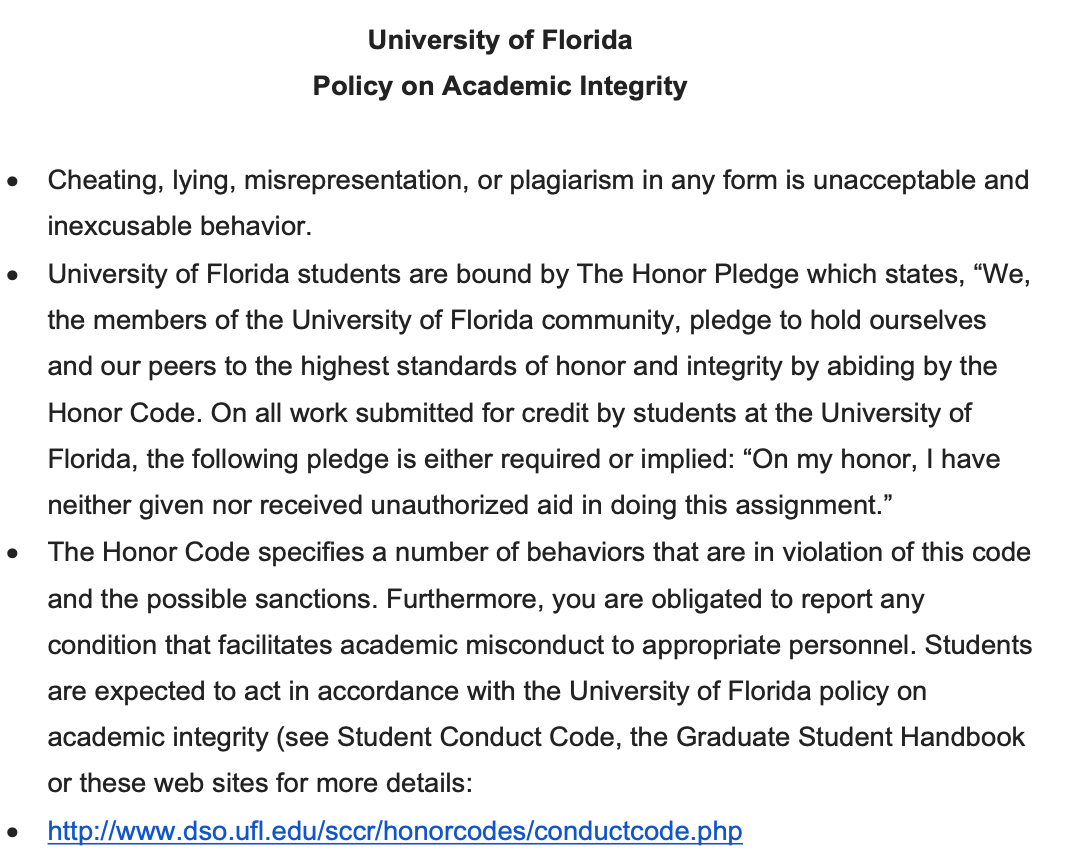

If you are a student in a course, you need to adhere to these academic standards. Figure 4 shows another passage from a University of Florida course that I've taught, and you can see they're all about the same. These guidelines are all expelled out in university policies and regulations, and every student should read the syllabus.

Figure 4. Example of ethics in an academic setting. Statements from AuD course syllabi.

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest

I mentioned earlier that periodically we need to disclose any conflict of interest. Sometimes a conflict of interest will not be all that serious; it will be accepted as long as you disclose it. As long as you are not deceitful about it. For example, if I'm teaching at one university, but I'm not full time, I can certainly teach another university with the free time that I have. I could give a lecture and get paid if I took a vacation day, but I do need to report that. It's a potential conflict of interest and some administrative superior like a department chair, and then maybe a dean will need to approve that behavior. If you are about to do something and you think perhaps it would be perceived as a conflict of interest, then ask your superior if you need to disclose that in writing.

Ethics in Audiological Practice

I want to discuss how ethics plays such an important role when you are a clinical audiologist and how you conduct yourself. There are many examples of violations of ethics in audiological practice. Many of them involve money. Many of them include some financial compensation, but not all.

Examples of Violations

Falsifying clinical records. Not only would that be an ethical violation, but that also would be a legal violation. This might be a simple thing of putting down a different date, indicating that a person had a particular test, or certain test results were not true. There are audiologists and many other health professionals that have found themselves in big trouble for falsifying clinical records, mainly when they should have done something, and they did not and wanted to deceive someone.

Sexual harassment and misconduct. This can certainly occur and in an audiology clinical setting, and it's a very common form of ethical violation.

Billing for services not provided. In other words, fraudulent claims. Whether it's intentional or unintentional, it is still fraud.

Offering a free hearing test as a Medicare provider. Again, sometimes you may think you are doing the right thing, but you may be behaving unethically.

Providing audiology services without a license. Your license may lapse. There may be a period where you are not licensed, and you want to continue providing services. I've had staff members who let their license lapse and provided services. As soon as I found out, I reported it. We went to legal counsel, and with the federal government, in the United States, Medicare or Medicaid, you must pay all that money back.

Failure to report unethical conduct. Even though you are behaving ethically, you still need to report unethical behavior that you are aware of promptly.

Vendor or Manufacturer Related Violations

Inappropriate gifts to and from patients, referral sources, or vendors can violate ethics. I won't get into all the details involving vendors and manufacturers, but when you think of ethics in audiological practices, this is what comes to mind. This is a big focus of the American Academy of Audiology Code of Ethics. The Ethics in Audiology book that I referenced earlier covers this in great detail. We don't have time to do so today, but if you are in clinical practice, whether you are in the United States or elsewhere, I would strongly recommend that you read those documents. These will help you understand precisely what is ethical and what is unethical. Sometimes it's quite clear, but sometimes it may not be. There are limits to how much you can accept before it is considered unethical, and we're going to talk about that more in just a second.

- Inappropriate gifts exceeding limits

- Inappropriate manufacturer" incentives" (kickbacks)

- Discounted hearing aid pricing

- Lease of clinic space

- Business development funds

- Free advertising

- Use of referral

- Inappropriate referral source relationships

- Use of referral pads

- Quid pro quo

- Gifts exceeding limits

Manufacturer gifts. This comes up all the time. If you are offered a gift or free dinner, can you take it at all? Should you refuse all gifts? Or are there some levels of gifts that would be appropriate? The American Academy of Audiology has very clear guidelines from the 2017 document. They've used the limit of $50 as the cutoff. Anything under $50 would be appropriate in most cases. Anything more than $50 is probably not appropriate. Now, gifts that might influence your clinical decisions are the most concerning. Other gifts, for example, software that will help you fit a hearing aid that is part of your clinical practice, would not be considered inappropriate. Demonstration units, proprietary software cables, something you need to use with a specific hearing aid, for example, it's not a gift. This is something that you need have to have to provide the service. There's no cost for it. You can not pay for it because it's not being sold to you; it's just being provided.

Other items. These are things like pads and pens. There has been a lot of debate and discussion certainly in the American Academy of Audiology about this. Some say you shouldn't have any gifts at all and I will say that when it comes to pads and pens, the best thing to do is not use them. I tend to get most of my pads and pens from hotels rather than from vendors. If you are writing out notes on your patient and they are watching you do that with a manufacturer's name on the pen, and you are turning around saying you need to buy these hearing aids. Of course, the patient will wonder well, what kind of connection does this person have to the manufacturer?

What is considered a gift? Now, there are other guidelines for what constitutes a gift. The Office of Inspector General, which is the federal government in the United States, has its guidelines. You certainly might need to follow these guidelines if you are working in certain settings. An institution might say, you must follow federal guidelines for gifts. So even though those guidelines might be stricter than the American Academy of Audiology, you still need to follow them.

Questions to Ask Yourself

Whenever these issues arise, try to think back to the principles as a starting point. How would your patients feel about your relationship? Would they view this with concern? Would you want your patients to know about it? If the answer causes any doubt, then you should not do it. How would your colleagues view you and your ethical behavior based on this association? Would you tell them about it? Would you want your details of involvement made public? The disclosure of conflict of interest forms that I showed you earlier, essentially does that. Is your professional judgment biased or influenced by whatever relationship with the vendor? If it is, and you are not acting like a true professional because it's an unethical activity.

Confidentiality Statement

In any clinical setting, I've always had to sign confidentiality statements, involving health information. This is a reminder that professional health information is protected, and I have agreed that I will maintain confidentiality when it comes to patient information.

Ethics in Audiology Research

Many of the principles that we've already discussed certainly apply when it comes to ethics in auditory research. One of the big concerns is to make sure that any research that you do is approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). We used to call it the Human Subjects Committee. You can not conduct research involving humans or animals of any type without first receiving approval by your institution. That is a critical step; if you don't do that, you are going to get yourself in a tremendous amount of trouble. You might even lose your job. You can not publish any papers unless you document to the publisher of the journal that you have complied with the IRB. So you have to have a proposal accepted, approved, and the informed consent for the participants or subjects must also be approved. Specific populations like infants, comatose patients, those who are cognitively impaired the requirements for research in those populations is even more rigorous. This is because they can not decide as to whether or not they participate. This is a fundamental concept, and if you are in any research setting, you will have to take courses and in-services to ensure you understand how vital IRB approval is for research.

Now, if you are submitting an article for publication and it involves subjects, you must also get the patients to sign a consent form. Very often, that has to be given to the publisher before they'll publish your paper. They don't want to get in trouble for publishing information that might violate the patient's confidentiality and privacy. This is very important when it comes to academic auditory research to always have consent forms and informed consent forms. Always make sure that you are not violating the subject's confidentiality.

Ethical Decisions and Dilemmas

Okay, ethical decisions and dilemmas. Here are just a few kinds of case scenarios:

- You are requested to sign results for tests that you did not perform (e.g., another audiologist or a technician that is not licensed). Well, the answer is you do not do it. Sometimes you may be under tremendous pressure to do that from some higher-level administrator, or there might be financial pressure.

- A manufacturer vendor offers to take you out to dinner, provide lunch for the audiology staff, or provide the cash gift to be used any way you want. Those are generally considered inappropriate. In most cases, you'd want to ask your superior or simply refuse, that's the simple thing to do.

- During your clinical interactions with an adult patient or parent of a pediatric patient, you suspect some type of abuse of the patient. It is unethical not to report it, no matter how difficult. This is where you want to consult with your superior.

Okay, here are some of the key references I've mentioned:

- American Academy of Audiology Code of Ethics (www.audiology.org)

- American Academy of Audiology Ethical Practice Guideline for Relationships with Industry for Audiologists Providing Clinical Care (2017). (www.audiology.org)

- Callahan et al. (2011). Ethical dilemmas in audiology. Contemporary Issues in Communication Sciences and Disorders, 38, 76-86

- Ng et al. (2019). Clinician, student, and faculty perspectives on the audiology-industry interface: implications for ethics education. International Journal of Audiology, 58, 576-586

Citation

Hall, J. (2019). Ethics in audiology today. AudiologyOnline, Article 26533. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com