Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar Increasing Confidence in Counseling Pediatric Patients and Their Families, presented by Michael Hoffman, PhD.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Explain how to utilize specific communication techniques for increasing alliance and connections with families.

- Discuss ways in which cultural considerations and multicultural identity may be impacting comfort in communicating with families.

- Identify specific standardized tools for measuring psychosocial functioning that can be used to screen patients and families for psychosocial supports.

Overview/Agenda

This course aims to cover a variety of topics. It is packed with information designed to provide a solid primer on different subjects that will, hopefully, increase your confidence. Our main focus areas include explaining strategies and tools to improve communication with patients and their families and fostering a sense of buy-in and understanding.

We will also discuss how cultural considerations and multicultural identity can impact comfort levels in communication and counseling with families. As a psychologist, I believe it is crucial to consider and respect culture when supporting and counseling families. Furthermore, we will identify specific standardized tools for measuring psychosocial functioning. This will not be a comprehensive discussion on standardized tools for screening, as that could easily be a multi-part series. However, if you are interested, I intend to briefly touch on this topic and offer some ideas to encourage further research.

Who Am I

I am a deaf adult with a hearing aid in one ear and a cochlear implant in the other. I was diagnosed with Connexin 26 as part of a genetic study years ago, which is the cause of my non-syndromic hearing loss. I have bilateral, moderately severe to profound hearing loss. Fortunately, I was diagnosed early, at five months, and received my hearing aids at six months.

Throughout most of my life, I was bilaterally aided until I received a cochlear implant at 28 while in grad school. This extensive experience as a patient in various medical systems, including pediatric hospitals, university training clinics, private practices, and adult care, influences how I work with the families I see professionally. I hold a PhD in Clinical Psychology from the University of Miami, where I specialized in pediatric health psychology, focusing on children with medical complexities or chronic illnesses.

My clinical training at Miami spanned numerous areas and pediatric populations. I provided integrated behavioral health services, including audiology and otolaryngology clinics, inpatient consultations, craniofacial, plastics, diabetes, endocrinology, and more. After my training, I completed my internship and fellowship at Nemours Children's Health in Delaware, where I stayed for six years, including four years as faculty. Recently, I joined the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), which holds personal significance as I was a patient there as a child, and I am a pediatric psychologist in the Center for Childhood Communication.

This diverse background as both an individual and a professional gives me a unique perspective when working with individuals who are deaf and hard of hearing. I have encountered people from all walks of life with a wide range of experiences. It is an honor to support families as they navigate these challenges, and it means a great deal to me.

Confidence in Counseling

As I prepared this presentation, one key area we wanted to address was counseling. Over the years, I've heard from many audiologists and colleagues that they wished for more comprehensive training while taking a counseling course in grad school. This sentiment is common among the professionals I've spoken with.

Interestingly, an article by Muñoz, Price, Nelson & Twohig1 surveyed 350 pediatric audiologists across the U.S. about their competence and comfort in counseling families. It's a worthwhile read. The survey revealed that 75% of respondents felt counseling is very or extremely important. This consensus underscores the need for audiologists to be comfortable and proficient in counseling. However, the survey also highlighted a significant challenge: 75% of respondents acknowledged moderate or greater difficulty in assessing psychosocial challenges and finding the time to address these needs.

This dual recognition—of the importance of counseling and the barriers to effective counseling—formed the backbone of this presentation. If you feel uncomfortable or that your counseling skills are a work in progress, you're not alone. Most of your colleagues share this feeling and are seeking more training. Your efforts to improve your skills and seek out additional training are commendable.

Communication Strategies to Improve Counseling and Therapeutic Alliance

Being a Person and Establishing Rapport

- Take a moment to talk to the family

- Introduce yourself and make eye contact

- Make discussion outside of your medical scope

- Ask the family how they are doing

- Ask about something outside of their medical needs and remember it!

Let's explore communication strategies to enhance counseling for therapeutic alignment without further ado. My approach is to offer concrete, specific strategies that you can immediately implement in your clinic—perhaps even today.

The first strategy may seem obvious, but it is crucial: remember to be personable and establish rapport with the families you see. Often, we find ourselves in the middle of a hectic day, running back and forth with a packed schedule and numerous tasks on our minds. However, it's important to take a moment to connect with families. Introduce yourself, make eye contact, and say hello.

I can recall numerous times when doctors or nurses have called me back without even looking at me, appearing miserable to be there. This lack of engagement can leave a negative impression. When I greet families, I make a point to make eye contact, introduce myself, and engage in small talk outside of the medical context. Simple questions like, "How's your day going?" or "How was it getting here?" can make a significant difference.

In Philadelphia, for instance, I often bring up local sports, as it's a big topic in the area. Asking families about something outside the medical visit immediately establishes rapport and comfort. They might think, "Hey, that person is pretty nice." This small effort, quick and easy to implement, can have a high payoff, yet it is something we often overlook or cast aside when caught up in our busy days.

Normalizing

- Normalizing is one of the most powerful tools you can use

- Patients and families are often wondering if their problems are unique to them

- Results in disclosing anxiety/discomfort or further discussing

- “A lot of children will say..”

- “Many others frequently tell me”

- “Given your history of hearing loss, I would expect it to be…”

- “This is very common among other parents of children with cochlear implants”

When working with patients and their families, one of the most powerful tools you can use as a psychologist is normalizing their experiences. This concept is fundamental in counseling, social work, and psychology training. Supervisors and attendings often emphasize normalizing as a crucial method to support families.

When patients and families come to the hospital or clinic, they are usually dealing with challenges or differences that concern them or their children. They may feel anxious or have numerous questions, wondering if their experiences are unique or if others face similar issues. Normalizing their experiences by saying something like, "Yes, that's what we hear from many families," can significantly comfort them. It helps take the edge off and often leads them to disclose their anxieties or discomfort, opening the door for further conversation.

You might wonder how to effectively normalize a patient or family's experience. Here are some examples:

- "Many children say that it's really hard to hear in the lunchroom at school."

- "A lot of children find it very overwhelming in the cafeteria."

- "Many others frequently tell me they don't like the FM system and find it difficult to hand it to their teachers or explain it to substitutes. Is that what it's like for you?"

- "Given your history of hearing loss, I would expect that feels pretty stressful or overwhelming for you. That makes total sense to me."

- "It's common for parents of children with cochlear implants to struggle with the decision about pursuing implants. It can be really tough."

Normalizing and validating what a parent, caregiver, or patient tells you makes them feel heard and understood. This approach can lead to more open and productive conversations.

Reflective Language

- How do you show your patients that you are listening to them?

- “If I am understanding you correctly…”

- “It sounds like…”

- “What I am hearing is…”

- “I get the sense that…”

- “It feels as though…”

- Reflecting back to them: Using downturns instead of upturns

- Upturns indicate a question

In addition to normalizing, another essential counseling strategy is the use of reflective language. This technique demonstrates to patients that you are actively listening to them. In psychology, and likely in most medical fields, new therapists often find their minds racing with what to say next, which can hinder their ability to be fully present and attentive to what the patient or family is expressing. With experience, therapists learn to listen carefully and respond in real time.

Reflective language helps convey that you are genuinely hearing your patients. For instance, you might say, "If I’m understanding you correctly, you find the hearing aids really uncomfortable. It sounds like you wear them at school but usually take them off when you get home." Or, "What I’m hearing is that you really like the hearing aids and feel they work well for you, but there are some aspects you dislike." Another example could be, "I get the sense that based on what you’re sharing, your family is struggling quite a bit with accepting this diagnosis."

When using reflective language, it's important to employ a downturn at the end of your statements rather than an upturn, which indicates a question. Upturns sound like this: "Hey, do you want to go get some ice cream?" When I say "ice cream," my vocal tone rises, indicating it's a question expecting a response. In contrast, a downturn sounds like this: "Hey, I want to get some ice cream," or "I would like to get some ice cream, too." Here, my vocal tone falls at the end, indicating a statement rather than a question. For example, "I sense you’re feeling frustrated" versus "I sense you’re feeling frustrated?" The downturn conveys a statement rather than a question, which reinforces that you are reflecting rather than querying.

The beauty of reflective language is that it leads to one of two outcomes. Either you accurately encapsulate the patient’s feelings, leading them to think, "Yes, Dr. Hoffman gets it," or you open the door for correction and further explanation. If you reflect and it’s not accurate, the patient has the opportunity to clarify, allowing you to reprogram and redirect your understanding. For example, "If I’m understanding you correctly, A, B, and C" invites the patient to confirm or correct your interpretation.

Using reflective language and normalizing are two of the most effective skills in counseling families. They help ensure that families feel heard and understood, fostering a more supportive and empathetic therapeutic environment.

Avoid Being the Finger-Wagger

- Most often, our desire is to provide information

- “This is why you should do what I am telling you to do!”

- We get frustrated when we feel like families are not doing what we are telling them

- We are providing information to invoke a behavioral change

- However, extensive research has shown that education is not sufficient to produce behavior change2,3

Paired with reflective language is what I like to call avoiding being the "finger wagger." We all know the finger waggers—it's almost ingrained in our DNA. As clinicians, we often have the urge to share our knowledge and expertise, which can come across as "This is why you should do what I'm telling you to do."

Consider this common scenario: when I go to the dentist every six months, they ask, "Hey, Mike, have you been flossing? Do you floss twice a day? Do you brush twice a day?" This isn't new information to me; I know I'm supposed to floss. Yet, their finger-wagging approach doesn't suddenly make me start flossing twice a day.

Similarly, if my primary care physician tells me to lose weight or drink less during an annual check-up, it doesn't lead to an epiphany. The same applies in our context: telling a family that their child needs to wear hearing aids all the time isn't new information to them. Wagging a finger and shaming them will only make them defensive.

Research shows that simply providing information does not drive behavioral change. You've likely experienced this firsthand: you're talking to a family, giving them information, counseling them on what they should do differently, and you can see them glazing over, waiting for you to stop talking. You sense they're not going to follow your advice, but you push through your spiel anyway. We've all felt that frustration when families don't seem to listen. The reason is that information alone doesn't change behavior.

Connecting with families, understanding their perspectives, reflecting on their feelings, and moving toward problem-solving is a more effective approach. If you find yourself on one side, telling them what to do, while they are on the other side, either passively receiving the information or arguing against it, it won't work well. Be mindful of when you start becoming the finger wagger. If you catch yourself getting in people's faces and "giving them the business," recognize that this approach is likely ineffective. Instead, strive to engage in a dialogue that fosters mutual understanding and collaborative problem-solving.

Reactions to Lecturing

- What reactions have you experienced with challenging families when providing education?

- The patient/family is likely to:

- Become defensive

- Become closed off

- Justify/explain their current views and behavior

- Feel misunderstood

Another way to build on what I was saying is to think about how families react to lecturing. When we tell families, "You need to do what I say," and provide a lot of education, we often see negative reactions.

Families may become defensive, closing off from the conversation. They might pivot to justifying or explaining their current views and behaviors, indicating they feel misunderstood. This defensive stance can hinder effective communication and collaboration. Recognizing these reactions is key to adjusting our approach and fostering a more open and productive dialogue with families.

Roll with Resistance

- You are experiencing resistance

- If you find yourself experiencing resistance or on opposite sides of a discussion with a patient, ask yourself:

- “How can I roll with the resistance?”

- Don’t go into autopilot

- Call it out and gather more information

- Find a middle ground. Is there a compromise to be had?

- If you find yourself experiencing resistance or on opposite sides of a discussion with a patient, ask yourself:

A useful approach to counter these reactions is what I call "rolling with resistance." When you're in a counseling session and notice that the family isn't receiving your advice well, it's crucial not to go on autopilot and finish your spiel. Instead, pause and address the resistance directly.

You might say, "I can see you're feeling a little frustrated right now," or, "I want to be honest. I know we've had this conversation many times, and this information isn't new to you. Would you mind telling me what's going through your head or how you're feeling right now?" By doing this, you open the door for dialogue and understanding.

Finding a compromise or middle ground can be incredibly productive. This approach, where you pause and acknowledge the resistance, leads to a more helpful and meaningful conversation than simply moving through your prepared remarks and onto the next patient. Engaging in this way shows that you value their perspective and are committed to working collaboratively to find solutions.

How to Provide Information

- Asking permission: When providing information, asking for permission can get more buy-in

- “Is it OK with you if I tell you about…”

- Asking permission makes the patient feel like they are in some control of their own visit

- When patients and parents are in critical care settings, they often feel like everything is being dictated to them

- If they say “no” (which is rare), they likely were not ready to hear any information

You might be wondering, "Mike, there are times when I need to counsel and provide information to families, right? I have a lot of valuable education, knowledge, and training. How do I reflect that?" Absolutely, there are effective ways to do this. Here are some of my "Jedi mind tricks" for better engagement.

First, ask for permission. This strategy can generate more buy-in from the family. For example, you might say, "Is it okay if I tell you about some different options for hearing aids?" or "Is it all right if I share information about the three different cochlear implant companies that might be options for your child?" Think about your own experiences in medical settings, where being poked, prodded, and tested can feel dehumanizing. Offering a choice gives patients and families a sense of control over their experience, making them feel less like everything is being dictated to them.

You might be concerned, "What if they say no?" That's a valid question, but it's rare for someone to refuse. If they do, it likely means they're not ready to receive that information anyway. They probably wouldn't retain it if you gave it to them. On the other hand, if they agree, they’ve committed to listening. When they give you permission, they are more likely to pay attention and engage with the information you provide.

By asking for permission, you either get them to commit to hearing more or recognize that they need space before they can engage. This approach respects their readiness and promotes a more collaborative and effective conversation.

Communicating With Children

- If they are old enough to ask the question, they are old enough to receive the answer

- Be open and honest with them

- Match their developmental level

- This might require being broad or simplified

- If you don’t talk with your kids, who knows where they land?

Another question that often arises, especially for me as a pediatric psychologist working in pediatrics, is: What are the guiding principles or rules for communicating with kids? We've all encountered parents struggling with how to discuss medical issues, whether it's related to audiology, a syndrome, hearing loss, or any other concern. Here are some tried-and-true rules:

- If a child is old enough to ask a question, they’re old enough to receive an answer. When a child asks a question, they are already thinking about it. We miss the chance to guide and shape their understanding if we dismiss or avoid their questions. Whether it's "Why do I have these hearing aids and no one else does?" or "Why did this happen?"—address their curiosity openly.

- Be open and honest. Children have a keen sense of when they're not being told the truth. They might not pinpoint exactly what’s off, but they can sense dishonesty.

- Match their developmental level. It’s crucial to provide truthful information that matches their developmental level. Simplify your explanations if needed, but always remain truthful. Tailor your responses to be appropriate for their age and understanding. Use simple, broad explanations for younger children and more detailed ones for older kids.

Avoiding difficult conversations can lead to children coming up with their own, often inaccurate, explanations. Teenagers and tweens, in particular, may seek answers online or from friends if their questions are not addressed at home. As caregivers and clinicians, shaping these discussions and providing accurate information is essential.

When counseling families, empower caregivers with these guiding principles to help them feel confident in discussing difficult topics with their children. Remind them that they play a crucial role in shaping their child’s understanding and perspective on their condition. Remember that we are not just treating the medical diagnosis but the whole patient and their family. Acknowledge their entire experience and existence to make them feel supported and understood.

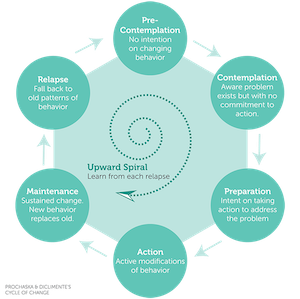

Engaging Patients in Behavior Change

This section briefly introduces the Stages of Change Model by Prochaska and DiClemente, first researched and published in the early 1980s. As seen in Figure 1, this model outlines five or six stages of behavior change, providing a framework to understand and support patients through their journey.

- Pre-contemplation: The individual is not considering changing their behavior.

- Contemplation: The individual recognizes there is a problem and begins to think about addressing it but hasn't made any plans.

- Preparation: The individual acknowledges the problem and starts planning steps to change the behavior, intending to take action soon.

- Action: The individual actively implements behavior changes.

- Maintenance: The individual sustains the behavior change for an extended period, typically around two years.

- Relapse: The individual may fall back into old behaviors, necessitating a restart of the cycle, often spiraling upward toward lasting change.

Understanding these stages can help in counseling families, especially in challenging situations. Identifying where a family is in this model can guide you to meet them where they are. For instance, if a family is still in the contemplation stage, pushing them directly into action may be ineffective and counterproductive.

When you recognize that a family hasn't yet acknowledged the issue (pre-contemplation) or is only beginning to consider change (contemplation), your approach should be different than if they are preparing for or already taking action. Tailoring your counseling strategies to their current stage can enhance your effectiveness and foster a more supportive environment.

I encourage you to explore further readings on the Stages of Change Model to better understand this model and its application. This foundational knowledge can significantly improve your ability to support families through their behavior change journey.

Figure 1. Prochaska and DiClemente’s Stages of Change (1983)4.

Another valuable psychological approach I’m a huge fan of is Motivational Interviewing (MI). You don’t need to be an expert psychologist or licensed mental health professional to use it. The idea behind MI is to elicit change and encourage behavior change in patients when counseling families.

The goal is to get them to start new patterns and develop new motivations. Here’s a quick overview of how MI works:

Ask Open-Ended Questions:

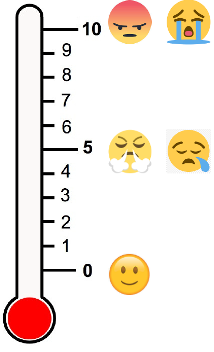

- For example, ask, “On a scale of one to ten, how much do you like your hearing aids?” Figure 2 shows an example of a scale to use with children.

- Define the scale, where one is “I totally want to throw them in the trash and burn them,” and ten is “I love them; they’re the absolute bee’s knees.”

Elicit Self-Motivation:

- If the kid says they’re at a three or four, follow up with, “Okay, help me understand why you’re a three or four and not a one. What makes you a three or four?”

- This approach gets the patient to articulate positive reasons for their behavior. For instance, the kid might say, “I like the Bluetooth, and it helps me hear my teacher sometimes.” This way, they talk about the benefits themselves.

Explore Reasons for Change:

- Questions like, “What makes you think you need a change?” or “Why do you think your parents care so much?” can be effective.

- Also, “What do you think will happen if we don’t make a change?” encourages them to consider the consequences.

The whole idea behind motivational interviewing is to get the patient talking about the behavior change they might want to make, focusing on them talking more and you talking less.

Figure 2. Scale from one to ten to use with motivational interviewing.

Cultural Humility and Cultural Competent Care: Our Role

We Are Cultural Beings

- Part of counseling families is to acknowledge the role that culture plays

- The human experience is diverse, and your counseling cannot be one-size-fits-all

- Ignoring the role of culture is like ignoring the water when you are in a pool

We are all cultural beings, and culture is an integral part of us. When counseling families, it's essential to acknowledge the role that culture plays. The human experience is diverse, and our counseling cannot be one-size-fits-all. You must be flexible, willing, and able to adapt your counseling approach to fit the family in front of you. Consider how their culture, previous experiences, and identities are influencing their perspective.

I like to use the analogy that ignoring the role of culture in counseling is like ignoring the water when you're in a pool. Culture surrounds us, and failing to recognize or acknowledge it makes effective counseling challenging.

How Culture Shows Up

- Language used – modeling person first language

- There is plenty of research regarding racial/ethnic inequities in care

- Are you actively taking steps to address this?

- Identifying and acknowledging barriers to care

- Calling out differential handling of patients

- Recognizing and identifying medical mistrust

- Statements of frustration from providers toward families

You might wonder, "How does culture actually show up in the room?" Culture manifests in various ways, including the language we use. There’s an ongoing dialogue about modeling first-person language versus disease-specific language. For example, debates around terms like "deaf" versus "hearing loss," "loss" versus "disability," and "autistic person" versus "person with autism" reflect cultural and identity differences.

Additionally, there is substantial research regarding racial and ethnic inequities in healthcare. In the U.S., significant disparities exist for Black families, Latin families, and families of color compared to White families. While I won't cover all of that here, it's crucial to consider how you're actively addressing racial inequities in healthcare.

Acknowledging barriers to care and recognizing differential patient handling is essential. Consider families with a history of medical mistrust who may be skeptical of the healthcare system. For instance, if a patient appears to be in denial, ask if there are issues of medical mistrust or past harmful experiences at hospitals. Is there a history of medical trauma?

Even among our own teams, statements of frustration from one provider to another about families can reflect underlying cultural and identity issues, as well as racial inequities. All these factors are intertwined, and it's vital to consider them when counseling and supporting families. Recognizing and addressing these aspects can lead to more effective and empathetic care.

Intersectionality

- Oxford dictionary5: The interconnected nature of social categorizations such as race, class, and gender, regarded as creating overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage”. - Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989

- Intersectionality involves negotiating one’s own diversity and figuring out how to express that with clarity and confidence in different settings

- Environments include home, school, spiritual/religious groups, cultural and geographic community

- Codeswitching – changing our behaviors (speech, dress, and mannerisms) to conform to a different cultural norm than our authentic selves

Tied into this is the concept of intersectionality. According to the Oxford Dictionary, intersectionality refers to the interconnected nature of social categorizations such as race, class, and gender, which create overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage. This term, credited to Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, describes how these social categorizations impact individuals' lives.

Intersectionality also involves navigating one's own diversity and expressing it with clarity and confidence in various settings, such as home, school, church, synagogue, mosque, or cultural and geographic communities. For example, living in the Philadelphia area, a common greeting and farewell, especially during football season, is "Go Birds!" This cultural phenomenon reflects the identity of Eagles fans in the Delaware Valley.

Code-switching is another aspect of intersectionality, where individuals change their behavior, dress, speech, language, and mannerisms to conform to different cultural norms. For instance, in a professional presentation to colleagues, I am Dr. Hoffman. This demeanor is very different from when I play with my two daughters after school, go to the gym, or spend time with friends. My speech, dress, and mannerisms vary across these settings, reflecting how we adapt based on our environment.

-------------------------------------------------------

Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw offers a powerful depiction of intersectionality. Sylvia Duckworth has created a graphic showing intersectionality that highlights the different areas like race, ethnicity, gender identity, class, language, religion, ability/disability, sexuality, mental health, age, education, and attractiveness. Dr. Crensha said, "Intersectionality is a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, where it locks and intersects. It is the acknowledgment that everyone has their own unique experiences of discrimination and privilege. All these identities are constantly overlapping and influencing each other. When we think specifically about deafness, it’s just one piece of a family’s experience, but their understanding and view of deafness are shaped by their other identities.

For instance, I recently met with a family who had immigrated from Sudan and were Muslim. Their perception of and approach to deafness is understandably different from, say, a white family from South Jersey. Another example involves a patient I saw earlier this week with a new diagnosis of hearing loss. The mother is a medical resident from Morocco, and she shared how devastated she was upon learning about her son's hearing loss. In Morocco, many children with hearing loss don’t have access to services or hearing aids, leading to either nonverbal communication, signing, or significant language differences. For her, much of the grief she felt was rooted in her cultural background and past experiences.

Intersectionality also involves considering power and privilege. The Wheel of Power/Privilege by Sylvia Duckworth is a very good visual depiction of this. I reflect on my own experience: as someone who is deaf, I’ve lived with hearing loss my entire life. However, I am also a white, cisgender, heterosexual male from an upper-middle-class family with access to resources, including having a car. Because of these other identities that are closer to societal power, my experience of being a deaf person is relatively privileged. On the other hand, individuals who are deaf or have a disability may also carry other marginalized identities, compounding the challenges they face.

When encountering conflicts or challenges with families—especially when it feels like they’re not responding as we hope—it’s important to ask ourselves what other identities they might hold. Could the difficulties we’re experiencing be tied to those intersecting identities?

Why Culture Matters

- We should always strive to consider the intersectionality between multicultural identity and experience of illness/disability

- White, well-resourced families experience hospitalizations, medical treatment, and illness very differently than individuals/families of color and those with less resources6-8

Hopefully, I don't have to keep belaboring this, but culture matters. We should always consider the intersectionality between multicultural identity and someone's experience of illness or disability. It's a fact that well-resourced white families experience hospitalizations, medical treatment, and illness very differently from families or individuals of color with fewer resources.

If you are not actively questioning how to challenge or dismantle some of the inequities in our healthcare system, you are not contributing to dispelling the status quo. I hope we can start thinking more about how to address these issues effectively.

Deaf Identity Formation

- Identity transmission happens via three routes:

- Vertical transmission – From caregivers to offspring

- Horizontal transmission – From peers

- Oblique transmission – From other adults and institutions

- 95% of deaf kids are born to typically hearing families9

- Therefore: deaf identity is shaped through horizontal and oblique transmission

- Caregivers are also forming an identity of what it means to be parents of a deaf child

- Family must come to terms with what “deafness” means10

- In contrast – We never need to define what “hearing” means

- Caregivers are learning what it means to be parents of a deaf child

To be a little more specific, let's shift to deaf identity formation and how it works. What fascinates me is that identity transmission tends to occur via three routes:

- Vertical Transmission: This comes from caregivers to offspring. For example, my understanding of my religion is primarily shaped by the cultural traditions and experiences of my parents and grandparents.

- Horizontal Transmission: This is from peers of the same age.

- Oblique Transmission: This comes from other adults and institutions.

Most deaf kids (95%) are born into hearing families, which means the most common form of cultural transmission regarding what it means to be deaf does not come from caregivers or grandparents. Instead, this identity is often shaped through oblique or horizontal transmission from peers, other adults, teachers of the deaf, audiologists, speech-language therapists, social media, and schools for the deaf.

As kids and families navigate what it means to be deaf, they rely on these other sources for information. Caregivers, in particular, are also trying to figure out their own identity as parents of a deaf child. For families struggling to accept a diagnosis, part of the challenge may be accepting the idea that they are now parents of a deaf child and figuring out what that means. They need to shift their expectations and thoughts to embrace this new pathway.

It's also interesting that, in contrast, we rarely define what it means to be hearing. Typically hearing individuals don’t usually consider their hearing as part of their identity. The closest comparison might be the challenges during the pandemic with masking when it was hard to understand what people were saying, and hearing individuals had to lean in more. However, this temporary challenge doesn’t equate to the ongoing process of defining a deaf identity. Caregivers are trying to learn and figure out what it means to be deaf and to parent a deaf child.

Another interesting study is a recent literature review article covering 47 different studies assessing deaf identity in adolescence by Smolen & Paul (2023)11. The findings were fascinating. One key point is that deaf identity is inextricably tied to the technology available at different times. For example, what it meant to be severely or profoundly deaf in the sixties, seventies, and eighties without access to cochlear implants is vastly different from today, where such implants are available. My own deaf identity would be completely different without access to implants or hearing aids.

As technology evolves, so does the concept of deaf identity. We are currently on the brink of significant changes in audiology and speech and language therapy, particularly with advancements in gene therapies and treatments. These developments could further shift the meaning of deaf identity.

All identities, including deafness, are complex, fluid, and subject to significant change. I appreciate the term "DeaF" where F stands for Fluid, emphasizing that deaf identity is fluid and can shift and evolve. Identifying with Deaf culture is not in opposition to identifying with hearing culture; both have their own strengths and can coexist.

Psychosocial Screening

Let's move on to our last section: psychosocial screening. I wanted to touch on this because, instead of specific training and counseling, questionnaires and measures can be incredibly helpful in understanding where families are and providing a good starting point for counseling.

Why use standardized screening?

- It might uncover information not shared verbally

- It helps to eliminate bias

- It can be administered from the EMR prior to visits to reduce burden

- It can be scored quickly and automatically

- Can guide how to use your resources most effectively

Standardized screening can uncover information that might not be shared verbally. Patients are often more willing to disclose their feelings on a questionnaire, whether on paper or an iPad, especially if completed before their visit rather than in the moment during the appointment.

Using standardized screening helps eliminate bias by ensuring all patients are asked the same questions, regardless of the time available. This approach reduces disparities in the attention given to different patients.

Many of these measures can be distributed and completed beforehand if you are tied to a hospital system or electronic medical record. They can be automatically scored, flagging patients who may need more follow-up. This process allows you to determine which patients need more time and attention and which can be seen more quickly, thereby guiding your use of resources more efficiently.

Standardized screenings are valuable tools that enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of counseling by providing a clearer picture of patients' needs and helping to prioritize care.

Logistics

- What exact do you want to screen for?

- Who is doing the screening?

- How is it administered and scored?

- Leveraging EMRs/Digital options

- How do what's your follow-up plan?

When considering standardized screening, several logistics need to be addressed. First, determine what exactly you want to screen for and which patient populations will be screened. Next, identify who will be responsible for administering the screening. Will it be you, a nurse, a medical assistant, or another staff member? Decide on the method of administration, whether it will be through a questionnaire, the electronic medical record system, or another means. Additionally, establish the scoring process, determine whether it will be manual or automated, and consider leveraging digital options for efficiency.

Another crucial aspect is deciding what to do with the data once it is collected. Establish a clear game plan for handling and utilizing the data to inform patient care and follow-up. Addressing these logistics ensures that the screening process is thorough, efficient, and effective in guiding patient care.

Your Screening Targets

- Age range of screening

- Who is doing the reporting

- Caregiver/child

- Teachers

- Others

- Generally, multiple reporters is better

- Consider developmental/medical differences

- Be mindful of neurodiversity

When planning standardized screening, consider the age range of the individuals you want to screen. Are you targeting parents of young children, teenagers, or tweens? Determine who will be reporting: will it be the caregivers, the children themselves, or both? Sometimes, you might even want to include input from teachers, although this would be more intensive.

Think about whether there's someone else whose input would be valuable, such as a teacher of the deaf (TOD) or a service care coordinator. Although involving multiple reporters can be more burdensome and intensive, it is often important. Research indicates that discrepancies between parents' and teenagers' perceptions of the teenager's mental health can be predictive of behavior problems. For instance, if a parent thinks their child is doing great while the child feels they are struggling, this discordance is a red flag.

Also, consider developmental and medical differences in the measures you're using. Be mindful of neurodiversity and the specific needs of deaf children, who may have differences in language, linguistic skills, and reading abilities. Choose questionnaires that are language-friendly and appropriate for the individuals being screened.

What Exactly Do You Want to Screen For?

- General psychopathology and functioning

- Anxiety, depression, ADHD

- Academic performance

- Condition-specific challenges

- Trouble adjusting to a diagnosis

- Feeling different from others

- Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL)

- Parenting Stress

Another important consideration is deciding who you want to screen and what exactly you are screening for. Are you targeting general psychopathology, such as anxiety, depression, and ADHD? Or are you more focused on academic performance or condition-specific challenges like trouble accepting a hearing loss diagnosis, parenting stress, or feelings of being different from other kids? You might also consider broader measures like quality of life or parenting stress. There are many different areas you can screen for, and it's essential to identify the specific needs and objectives of your screening process.

A Brief (But Not Exhaustive) Review of Potential Screening Tools

Now that I've presented various considerations for screening, hopefully without scaring you away from its possibilities, here's a brief but not exhaustive review of potential screening tools.

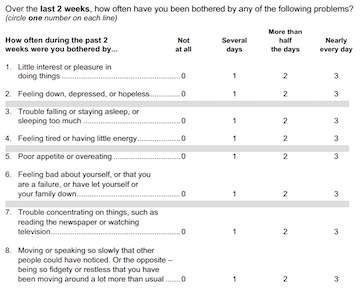

Personal Health Questionnaire Depression Scale (PHQ-8)12

Figure 3. Personal Health Questionnaire Depression Scale (PHQ-8).

The Personal Health Questionnaire Depression Scale seen in Figure 3, also known as the PHQ, is a valuable and free tool available through the NIH. It consists of eight or nine questions, with a shorter version focusing on symptoms of depression in the last two weeks. The PHQ is straightforward: sum up the items, and if the total score is greater than 10, it indicates major depression, while a score greater than 20 indicates severe major depression. This tool is particularly useful for identifying depressive symptoms in deaf children who may be at higher risk.

- The PHQ has an 8 and 9-item version

- The 9th question that is added/dropped is a suicidality question

- If screening for suicidality, you must be prepared with a plan to handle these positive screens

- What happens if someone is reporting active suicidal ideation?

- If nurses/others are administering the questionnaires, a contact chain protocol is needed

A quick aside: the PHQ has an eight-item and a nine-item version. The ninth item asks about suicidality, which is extremely important. If you choose to screen for suicidality, you must be prepared to handle it appropriately. Consider how you will manage kids who report active suicidal thoughts. Ensure you have a protocol or process to triage these cases and address potential legal liabilities associated with screening for suicidality. It's a crucial aspect of mental health screening but requires careful planning and preparedness.

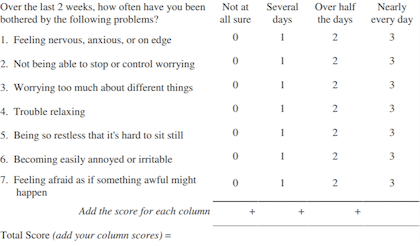

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item Scale (GAD-7)13

Figure 4. Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item Scale (GAD-7).

The sister questionnaire to the PHQ is the GAD-7 or the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale. This tool assesses symptoms of anxiety. Respondents answer seven questions about their symptoms over the last two weeks, and the scores are summed to categorize anxiety levels: a score of 5 indicates mild anxiety, 10 indicates moderate anxiety and 15 or greater indicates severe anxiety. Generally, a score of 10 or greater warrants a referral for anxiety treatment. The GAD-7 has a high sensitivity rating of 89% and a specificity of 82%, making it a reliable tool. It also correlates with conditions such as panic disorder (sensitivity 74%, specificity 81%), social anxiety disorder (sensitivity 72%, specificity 80%), and post-traumatic stress disorder (sensitivity 66%, specificity 81%). Many pediatric specialty groups, including endocrinology and hematology, recommend annual screening for anxiety and depression, and the GAD-7 is a good option for this purpose.

Health-Related Quality of Life Measures

Another option for screening is health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measures. If you're not familiar with HRQoL measures, they are designed to capture the daily experiences of individuals with chronic illnesses. These measures typically focus on four core domains: disease severity and symptoms, functional status, emotional and cognitive functioning, and social functioning. There are both condition-specific measures, such as those for deafness, and generic measures. The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) offers both generic and condition-specific options, making it a versatile tool for assessing the quality of life in various patient populations.

Examples of Measures

- PedsQL - https://www.pedsql.org/about_pedsql.html

- Has generic and condition-specific options

- PROMIS - https://commonfund.nih.gov/promis/index

- HearQL - https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/abstract/10.3766/jaaa.22.10.3

- Parenting Stress Index 4th Edition - https://www.parinc.com/Products/Pkey/333

The PROMIS is another free tool available through the NIH. The HEAR-QL is specifically designed for the deaf population, while the Parenting Stress Index measures parenting stress. I'm not highlighting all of these tools in detail here, but there are links available on their websites for further exploration. Some of these measures are free, while others may require a purchase. These are just a few options to consider if you are interested in looking further into different screening tools.

Questions and Answers

For families in denial of hearing loss diagnosis who challenge the reliability of your test results every step of the way, do you have any suggestions on how to counsel the family?

In situations where a family is not yet accepting or understanding the hearing loss diagnosis, it's common to want to present all the evidence. For example, you might be tempted to pull out the audiogram, walk them through it, or put them in the booth to watch their child's response to testing. This approach often falls into the pattern of giving all the information and expecting them to accept it.

Instead, I suggest pausing and acknowledging their efforts and feelings. For instance, you might say, "I appreciate you coming back for a few appointments. I know it's been hard and that these visits aren't easy for you. I can tell you sometimes get emotional when we discuss the potential of hearing loss. Can you tell me what's going through your mind or what your thoughts are?"

You could also ask, "Are there things you feel I can go over or help you understand better?" Another approach I often use is, "I can see what's in the medical chart and what other providers have told you, but can you walk me through your understanding of everything? Where might things be unclear for you?"

Additionally, asking about their feelings and implications can be insightful. For example, "I know this must be really hard. Can you tell me what it would mean if your child did have hearing loss or a hearing difference? How would that change things for you?"

You can better address their feelings and barriers by sidestepping the need to prove the hearing loss and instead focusing on understanding their perspective. This might include understanding their background or culture, which can play a significant role in their readiness to take the next step into devices.

Are the questionnaires free?

The PHQ (depression screening), GAD-7 (anxiety screening), and PROMIS are all free tools available through the NIH. The HEAR-QL, which is a quality-of-life measure specific to hearing, is also available. However, the Parenting Stress Index and some other tools may require a purchase. If you're looking to screen for anxiety or quality of life, there are definitely free options available.

When a child needs a hearing assessment as part of their psychosocial evaluation but is reserved and unwilling to participate, what tips can help build rapport and encourage cooperation?

My number one strategy is to be preventative. When I notice a child is shy and reserved upon entering the room, I try to get them to talk about themselves and something fun they enjoy. I generally have more time than most, with visits lasting an hour or longer, so I always spend the first five minutes getting kids to open up about something they like. Sometimes, I might poke fun at their parents in a light-hearted way. Being sarcastic can help lighten the mood.

Another approach is to pause and acknowledge their feelings. I might say, "I can feel that you're a little bit resistant or unsure. Tell me what's going through your mind." If they are hesitant about filling out a psychosocial questionnaire, I could ask, "I see you're hesitating. What are you thinking?" Drawing them out, giving them a break, or directly asking about their thoughts can all be helpful in building rapport and easing their resistance.

Do you feel these tools can be applied to high-functioning ASD or autism spectrum disorder clients, or do you have other screenings to help families identify for further assessment?

I would need to do some research to see if those specific measures have been validated for an autism population. Generally speaking, there is no reason why someone with autism couldn't complete these measures, provided they have the necessary language abilities, whether that is ASL, spoken English, or another form of communication. However, significant language differences might preclude someone from filling out the measure.

That's a great question and it also reminds me of the M-CHAT, an autism screening tool, which is also free. You might want to check it out if you're interested in autism screening as well.

References

- Muñoz, K., Price, T., Nelson, L., & Twohig, M. (2019). Counseling in pediatric audiology: Audiologists’ perceptions, confidence, and training. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 30(1), 66-77.

- Arlinghaus, K.R. & Johnston, C.A. (2017). Advocating for behavior change with education. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 12(2),113-116.

- Feldman, D.B. & Sills, J.R. (2013). Hope and cardiovascular health-promoting behaviour: Education alone is not enough. Psychology & Health, 28(7), 727-745.

- Prochaska, J.O. & DiClemente, C.C. (1983). Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51(3), 390-395.

- https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/us/definition/english/intersectionality

- Adler, N.E., Glymour, M.M., & Fielding, J. (2016). Addressing social determinants of health and health inequalities. Journal of American Medical Association, 316(16), 1641-1642.

- Baumann, A.A., & Cabassa, L.J. (2020). Reframing implementation science to address inequities in healthcare delivery. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 1-9.

- Williams, D.R. & Cooper, L.A. (2019). Reducing racial inequities in health: Using what we already know to take action. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(4), 606-632.

- Mitchell, R.E. & Karchmer, M. (2004). Chasing the mythical ten percent: Parental hearing status of deaf and hard of hearing students in the United States. Sign Language Studies, 4(2), 138-163.

- Leigh, I.W. & O'Brien, C.A. (Eds.). (2019). Deaf identities: Exploring new frontiers. Oxford University Press.

- Smolen, E.R. & Paul, PV. Perspectives on Identity and d/Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Students. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(8):782-796.

- Spitzer, R.L., Williams, J.B., & Kroenke, K. (1999). Patient health questionnaire: PHQ. New York State Psychiatric Institute.

- Spitzer, R.L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J.B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092-1097.

Citation

Hoffman, M. (2024). Increasing confidence in counseling pediatric patients and their families. AudiologyOnline, Article 29055. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com