Editor’s Note: This text course is an edited transcript of a Sivantos live webinar on AudiologyOnline. Download supplemental course materials.

Dr. Catherine Palmer: Welcome to our first 2015 Sivantos Expert Series.

Learning Objectives

Our learning objectives are: to define interventional audiology; to talk about three avenues for exploring interventional audiology in an audiology practice; to list the elements required to have a successful interdisciplinary clinic; and, to describe how audiology assistants/externs could play a role in providing interventional audiology under the supervision of an audiologist.

Thank you to Jenifer Fruit, AuD, for helping to put this presentation together. I would also like to thank Lori Zitelli, AuD. She has been instrumental in our Trauma Clinic. Lori is the lead audiologist in that clinic and has looked at the data behind interprofessional interactions.

Agenda

Once I have painted the picture of this introduction, we will talk about our Trauma Clinic here at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, wherein we play a role. Next, we will talk about what we call the HearCARE Initiative, and then we will talk a little bit about home health and hospice care.

Interventional Audiology

Interventional audiology means managing hearing loss in order to impact other primary concerns. Hearing loss is neither the person’s nor the other health care provider’s primary concern. As an audiologist, we might think it should be their primary concern, but we know it is not. We manage hearing loss in order to impact a different primary concern that is immediate or ongoing.

When you think of it that way, it automatically implies that we are either going to the professionals who are managing patients or interacting with these patients, or we are going directly to the patients.

In the examples I will give, the individuals are not being considered “patients.” We are going directly to where the individuals are, whether that is inpatient or outpatient, and that is where we want to perform some kind of intervention.

Interventional audiology was described by Taylor and Tysoe (2013), which referred back to interventional medicine. This is not a new concept. Why did medicine move in this direction? Generally, it is related to the increased costs of health care. One reason to have an interventional mindset is to bring costs down. That is an ongoing theme in large medical centers.

In our medical center, each meeting has a discussion about value of our care. Value is defined as the least cost for the most benefit. It focuses on preventing illness, which not only is an altruistic thing to do, but it brings down the cost of health care. Audiologists may not always think fiscally, but it is something that we need to evolve into doing. Many times, we think about how we are impacting someone’s quality of life and we are making things better, and I do not mean to minimize any of that, but when we are talking health care systems, administration understands fiscal savings. When we can position ourselves to use interventional audiology to reduce costs to save money, people listen in a different way and are quicker to see how these things can be implemented.

Along those same lines, the goal of interventional audiology is to minimize impairment and maximize function. When we maximize function, we will likely reduce cost. The more data we have, the more compelling that will be when convincing a large center of why you should implement something like this.

We are going to target patients whose primary concern is not hearing. Some of these people have a level of hearing loss that is so severe that we cannot understand how it is not their primary concern. We do have to accept, however, that that is the case. This is another way to reach these people who otherwise would not step into the test booth on their own. Clearly, these people did not come us, but this is a different model where we, instead, go to them in order to help them fix something that has become a much more pressing issue for them at this time.

Why Focus on Earlier Treatment for Hearing Loss?

Hearing loss interferes with a patients’ ability to be treated for other conditions. This is more obvious now than ever to other health care providers, partly due to popular press that has helped us and partly to more data in other medical journals where people are seeing hearing loss.

We know that hearing loss can accelerate or exacerbate other problems. We have forward-thinking researchers in our field who are putting audiology in a very good position. This prevention or early detection and treatment can likely result in improved quality of care. If you can hear what someone is telling you to do, you are more likely to do it. That should give improved outcomes, and all those things reduce overall cost of care.

If you happen to be in a medical center with a hospital, this is the concept of reduced readmissions. Given the changing health care climate for hospitals, when a patient has to be readmitted for the same condition within a certain time frame, they are not going to be paid for those services. That is the kind of conversation that is clear to a hospital administrator. They know exactly what that means. Being able to communicate and know what you were told to do when you leave, being able to use the phone to ask questions or to receive calls for follow up will impact an individual’s ability to stay out of the hospital. That is a very clear cost, which is more than an audiologist’s salary for a year. It is easy to have that conversation from a fiscal standpoint with the right people.

Impact of Untreated Hearing Loss and Poor Communication on Healthcare

Untreated hearing loss has an impact on inpatient care and outpatient care. The health care providers’ attitudes are infinitely important, and we have some work to do with other professionals. Sometimes demonstration is our best attack.

There are two stakeholders: the patients or individuals themselves and the health care providers. We have to deal with both groups to convince them that treating untreated hearing loss will make a difference. Let’s take a look at inpatient care.

Inpatient Care

Depending on what happened to this person to bring them to inpatient care, there may have been first responders that had to go to them. There is important communication at that moment in time with the emergency medical team and the emergency room physicians. Clear communication is vital so they can quickly discern the next action. Many times people in hospitals are wearing masks, which complicates communication further.

There may be patients admitted who have hearing loss and have managed on their own outside of this setting. They have mild to moderate hearing loss, and they might have done better if they had been a hearing aid user, but they are not, for whatever reason. They get by at home and in their familiar environments. A hospital, however, is a foreign environment and people are using unfamiliar terms, wearing masks, or have a foreign accent. All of those things coordinate to take someone who had a hearing loss that was managed reasonably to a situation where that same hearing loss makes them very compromised. Sometimes in these situations, the individuals feel compromised and recognize that they might need help now when they did not before.

They will need to understand test instructions while they are an inpatient as they are being asked to do different things. Additionally, they will need to understand the information that is being given to them throughout their stay, including their diagnosis and prognosis. This goes back to patients fully participating in their care. That is a metric now in quality control, and it is easy to have that conversation as well. You cannot fully participate in your care if you cannot hear and comprehend what is being said to you. Decision-making relies on the ability to take information in and give information back.

Another challenge is recovery and discharge. The person must understand the discharge instructions, which is confusing as patients are often discharged before they are feeling 100%, and it is difficult to retain complex information in that state. We expect them to fully know what to do next as they become an outpatient. There is no part of the hospital experience where you are not communicating with someone. You are either resting or you are communicating.

Outpatient Care

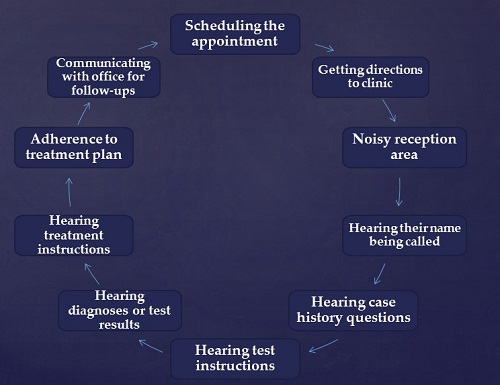

Let’s think about the outpatient experience (Figure 1). Either you were an inpatient and have become an outpatient, or you are someone who is pursuing outpatient care. It starts with communicating to schedule appointments and get directions, entering a potentially noisy reception area as you check in, hearing your name being called, and then you are right back in that communication loop as it pertains to care.

Figure 1. How communication can affect outpatient care.

You hear instructions, the diagnosis or results of what needs to happen, what kind of treatment options you have, and you are making decisions based on this. Hopefully you will adhere to some kind of treatment plan and communicate with the office for follow-up. That process does not end as outpatients. There is a lot of communication going on in both of these situations.

Providers’ Attitudes about Patients with Disabilities

It is interesting to look at some data regarding how health providers view disabilities. First, and this is common across society, health care providers look at accessibility as a matter of physical access only (Sanchez, Byfield, Brown, LaFavor, Murphy, & Laud, 2000). I do not mean to minimize physical access, as it is very important to be able to get to the appointment. However, if you cannot communicate once you are in, what good is that? We do not want to limit physical access, but we also want to expand that to what you are accessing once there.

It is also interesting that many physicians have a habit of referring patients with disabilities to other physicians (Grabois, Nosek, & Rossi, 1999) who they identify as the physicians who take care of “these people.” I do not know that this makes sense with any disability, but it certainly does not make sense with hearing loss. You cannot be sending all of those people somewhere else. Instead, we want to give these physicians some way to manage this within their office, even if the patient is not managing it.

Physicians indicate a lack of awareness of the American with Disabilities Act (ADA) and their obligation to serve patients with disabilities (Grabois, et al., 1999). Audiologists are in a good position to not only educate physicians and health care workers, but to give them simple solutions for communication in their offices.

The work of Dr. Brownyn Hemsley and colleagues shows that providers perceive many communication difficulties when serving patients with hearing loss. Providers are frustrated that there is increased time and effort. I think we can arm them with tools to decrease this frustration. Having these studies can help us have conversations with health care providers about what they might want to do in their clinics.

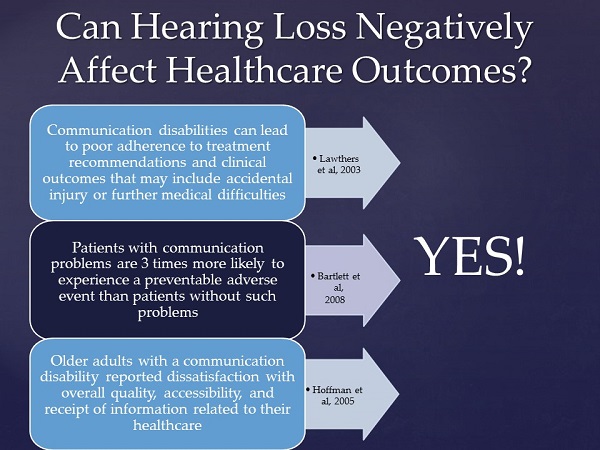

Can Hearing Loss Negatively Affect Health Care Outcomes?

We already know the answer is yes. It is important to know this information if you are trying to have this conversation. It is not enough to say we know that not being able to communicate is going to be a negative experience. Although it is an obvious conclusion, administrators want to have data. Figure 2 gives a few examples you can use.

Figure 2. Data supporting that hearing loss negatively impacts health care outcomes.

Communication disabilities can lead to poor adherence to treatment recommendations and clinical outcomes that may include accidental injury or further medical difficulties (Lawthers, Pranksy, Peterson, & Himmelstein, 2003). From a hospital’s point of view, bad events cost money. You might think that more illness or injury would mean more revenue for hospitals, but it is the opposite. They lose money now because they are not going to be reimbursed for some of the readmittance costs. The conversation is a little more compelling here.

People with communication problems are three times more likely to experience a preventable adverse event (Bartlett, Blais, Tamblyn, Clermont, & MacGibbon, 2008). The phrase “adverse event” is aversive to hospital administrators.

Older adults with a communication disability reported dissatisfaction with overall quality, accessibility, and receipt of information related to their health care (Hoffman, Yorkston, Shumway-Cook, Ciol, Dudgeon, & Chan, 2005). Any of you who work in hospitals know that satisfaction is the key indicator in hospitals. Many of us receive Press Ganey data reports at the end of a specified reporting period. We get our ratings of how satisfied our patients are. In audiology, we know that satisfaction and benefit are not synonymous. One of the real problems in fitting hearing aids is that we continue to see people who do not use best practices; they may fit the hearing aid so that sound is inaudible yet their patients are satisfied. These patients do not know what they are missing. They like the audiologist and they have been told the hearing aid will not solve everything, so they think this is as good as it gets. The satisfaction metric would say that they were just fine, whereas a metric of benefit would be low for them.

Be that as it may, current health care culture is all about patient satisfaction. It is very important that we have measurements to show that our patients are satisfied or we will start to lose money. It is a fiscal issue when you are taking Medicare dollars. We do not want people to be dissatisfied. The Hoffman et al. (2005) data are helpful so that we have a means whereby we can do something else cost effective to improve satisfaction. If nothing else, it shows that we are doing something about it.

Interdisciplinary Health Care

I do not think we are going to move towards interventional audiology if we are not practicing interdisciplinary health care. Interventional audiology implies that you are leaving your clinic and test booth and must be going somewhere. Chances are you are going somewhere where other people are doing things as well, and you are trying to team up with them and impact their care positively, as their care may be addressing the primary problem. Hearing loss would not be their primary concern at that time.

We have had interdisciplinary practices for a long time, but there seems to be a resurgence of the conversation. I imagine many of you have been on interdisciplinary teams for years, but we are now defining it more and talking about it. We are seeing it in accreditation standards; audiology programs have to show where they teach this, because we want the next generation of audiologists to be prepared to be part of a team and function at a doctoral level.

The resurgence may be partly because we have fewer primary care physicians (PCPs) and we need teams of other providers. The PCP does not have expertise in some of these areas, and they need other people at the table. Also, rising costs of health care demand that we integrate care in a more careful manner and make sure that someone is managing it so that people are getting what they need. This is all part of total quality management.

Interventional Audiology in the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center

Let me talk about the UPMC Falk Trauma clinic. We are a tertiary care center, so we see people who are life-flighted in, transported by ambulance, and come from at least three or four different states. We have had a trauma center forever, but in January 2014, we recreated our interprofessional Trauma Clinic.

The Trauma Clinic is for patients two weeks after they are discharged from our hospitals. The most common reason to be in our trauma department is a motor vehicle accident. The second most common is a fall of any kind. We also see violent assaults and a fairly large number of hunting accidents such as falling out of tree stands and shooting accidents. There are also work-related accidents and other accidents that should not have ever happened in the first place.

As I said before, people are often discharged sooner than maybe is ideal, so the Trauma Clinic was created so that two weeks later, patients could come back to an outpatient clinic and we can help them with what is challenging. Now they are in a better state to receive information and also relay their concerns.

In the past, they were seen by physician assistants (PA). But our lead PA, who I give a lot of credit to, one day thought that this did not make sense. We should have a team of people to see them all on the same day, which would save these people an unbelievable amount of stress. Remember they are all recovering from trauma; many are still wheelchair or stretcher bound. Would it not be ideal then to have everyone in one place? In the end, occupational therapy (OT), physical therapy (PT) and speech were immediately involved, and our speech colleagues suggested the need to involve audiology as well. Also included on the team is nutrition, rehabilitative counseling, nursing, medical assistants, and administration.

Speech, PT, OT, and Nutrition evaluate the person the day they are in this clinic to determine their current status and what needs to happen next. Then we have medical assistants and nursing staff making appointments for these patients so they do not fall through the cracks. They get a summary of what all they need and what to do next. The therapists are not providing therapy during this visit. They are making a plan for these people that the nurse will put into action, and then will follow up. The PA will take the final overall look at all of this information.

Factors Affecting the Success of Interprofessional Teamwork

These points can be helpful if you are trying to coordinate a team. First, the size of the team matters. You do not want it to be too large. The composition of members on the team matters. There needs to be a team leader on the day that everything is happening.

Stability is important when you have a team that is interacting with the same patients. You need the organization to support this. You want regular team meetings. The interpersonal relationships in any workplace are very important, and that goes back to the stability of the team. Everyone has to have the same goal. People have to understand their roles and appreciate those differentiations and where there is overlap.

You will need an auditing process and ongoing evaluation. It is important for the team to feel important, but also to improve what is happening. It is a work in progress. Make sure your team represents the different professions for what these patients need.

Our team leader is a registered nurse who makes sure everything flows well, and that person is the patient’s primary contact. The Outpatient Trauma Clinic happens two times a week, and they meet regularly in clinic about these patients. They hold larger meetings once every quarter to review the whole process.

Team goals are important so that the process is efficient for these patients. We want to do everything in one setting and have a concise follow-up plan where the nurse can make sure everything gets scheduled. Each team member is contributing, and then we get patient feedback.

Because we are a university, our health policy institute collects data and tracks some outcomes. We are trying to look at data to say whether patients who take advantage of this clinic do differently from patients who do not.

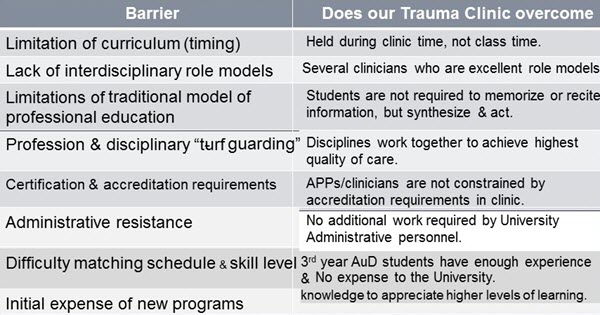

Education

We also look at this from the standpoint of education. Third-year Pitt students or fourth-year externs take part in this clinic with us. We consider it an advanced placement. What we do in this clinic is not complicated audiology in terms of testing, but it does have a level of complexity in that you must think on your feet, make decisions, and interact with other professionals. That is an advanced activity for a student, in our opinion. If you are trying to educate students and teach them how to function in an interdisciplinary team, Figure 3 summarizes some common concerns and how we have addressed them.

Figure 3. Common educational concerns addressed by the UPMC Trauma Clinic.

This is not a course activity; it is a clinical activity or assignment. There are many good clinician role models. There is no additional work here. It is an existing clinic, and we are integrating the students in it. Most of us do not even turn around without a student watching us do it. The students are very integrated in what we do, and it is a high-level experience.

Communication in the Trauma Clinic

The premise of the Trauma Clinic is about assessing where people are and then advising them on what to do. We play that role, but we also play a slightly different role from any of the other professionals in this particular clinic. We want to intervene first on the day of the clinic. If you are not hearing well, then the rest of the day is useless for you. It was interesting how quickly we got everyone’s support on that.

Working in a tertiary care center, there are times we absolutely need a test booth, and we work with three full time otologists. There are times when we want to be very carefully measuring hearing and thinking about site of lesion, but there is another part of our day where we do not need to know exactly how someone hears. That is generally uncomfortable for audiologists because so much of our training goes into knowing exactly how someone hears at every level of their system. I am not minimizing this part of what we do. However, there is a time to step away from that and determine if a person can communicate.

In many of these interventional places, we are not using the word hearing; we are using the word communicating. Unless we are specifically dealing with a problem with the ear, we are looking at how they are communicating. We do a screening, and then we identify what needs to happen today so they can access the rest of their day efficiently. With that in mind, we are also putting in recommendations of what should happen afterwards, depending on how much difficulty they are having.

This clinic is impacting what happens to other inpatients. It is impacting the PAs and physicians to do something while the patient is an inpatient. If, during this visit, we screen and realize the person has hearing loss that would have gotten in the way of communication, it means they had that when they were an inpatient in our hospital, and it means that we did not do what we needed to do for them on the inpatient side.

Screening

In the general population, 20% of people will not pass a hearing screening (Lin, Niparko, & Ferrucci, 2011). When you look at the whole population of the Trauma Clinic in 2015, it is about 42%. There is clearly a higher incidence with this group.

We are doing a simple screening with a handheld portable audiometer. We also have inexpensive amplifiers that we can put on these people for the day, and they take them off when they leave. We can repair personal hearing aids for those who have come in with hearing aids. We can also help patient, family, and staff in terms of communication strategies.

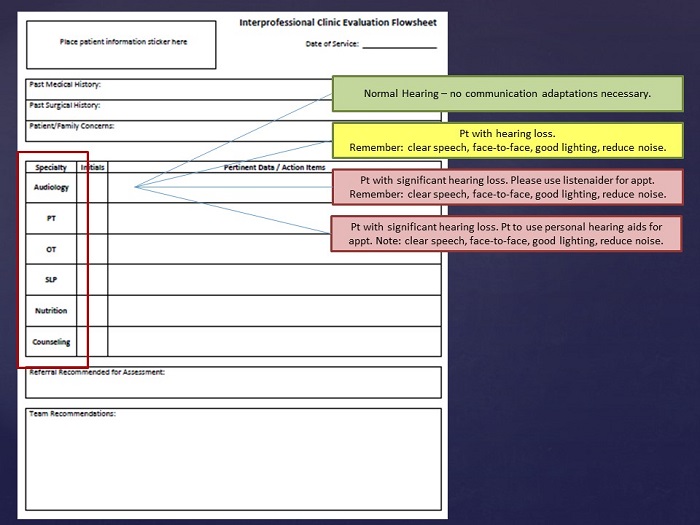

Figure 4 shows an intake form for a patient. We decided to use colored stickers, because we can quickly label what the other health care providers need to know. A green sticker with the writing on it means they are hearing you well and communicating. Yellow means there is a little bit of problem, not enough for an amplifier, but you want to be cognizant of that and make sure it is not noisy when you are communicating with them.

We have two red stickers. One says we have given them a listenaider, which is an inexpensive amplifier with a microphone, and the other says they are using their personal hearing aid. This lets the caregiver know that that is what they should be using when they meet with the therapists on that day.

Figure 4. Trauma Clinic evaluation flowsheet.

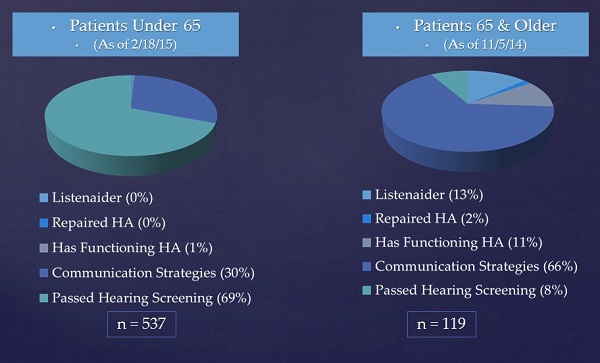

Figure 5 gives you some data of our patients under 65 and over 65. Ninety-one percent of our over-65 population need communication strategies all the way up to an amplifier. That is a huge percentage of the population and says something about individuals suffering from trauma. Thirteen percent needed an amplifier, which means they would have needed it in the hospital. We repaired hearing aids for 2%, which is small, but think how substantial that is for trauma patients to not have to go to yet another appointment to get their hearing aid fixed. They tend to be the most grateful people there.

Figure 5. Data from our Trauma Clinic for patients under age 65 (left) and over age 65 (right).

Helping Future Patients before Clinic Day

We also looked to see if we had a service to provide hearing tests and amplifiers on the inpatient side at all the hospitals we support. This was accessed every now and then, but certainly not as much as we would like it to be. There are different reasons for that.

In some ways, you have to be careful what you ask for. Given the data from the Trauma Clinic, you would say that most everyone over the age of 65 should be screened, and you could have an automatic consult for that in a hospital. You may or may not have the resources to do that. You may want some kind of risk assessment.

Using a risk assessment would help you think about whether someone is having hearing loss. This may be useful to help focus in on the patients who need a screening. Perhaps you have the resources to screen these people. We found that although we have had these programs in place for a long time, we did not know how it impacted people firsthand.

In the Trauma Clinic, the physicians and PAs have seen what happens when we put a simple amplifier on people. That has impacted their care on the inpatient side. After the first year of having the program, there was an 86% increase in our trauma surgeons consulting to audiology for patients who say they do not hear well. We will far surpass that this year as well. It is exciting to see that change.

HearCARE: Hearing and Communication for Resident Engagement

HearCARE is another thing we consider to be interventional audiology. The concept is for the population of assisted living facilities, independent living facilities, and skilled nursing facilities. For this project, which is funded by the Hearst Foundation so we can collect some quality improvement data, we are in assisted living facilities.

From other data, we know that that there is a high incidence of hearing loss in a group of individuals residing in assisted living, partly because of their age and partly because of some of their health conditions. Untreated hearing loss in these situations impacts their quality of life. It impacts caregiver burden, whether that is the staff or their family members.

Additionally, there is a relationship with cognition. We know that relationship impacts the burden of caring for someone as well. Interestingly, when you think about family members helping an individual make that decision to go into assisted living, part of assisted living is that the person needs a slightly higher level of care and monitoring. A big part of that decision is socialization. Physically, it is easy to access socialization as there are numerous social and physical activities in which one can engage. But oddly enough, members of our family go into these situations and they cannot hear. None of those perks of these places pay off for them. All of those activities are not accessed if you are not hearing well.

Other independent factors go into this, such as movie nights or enjoying TV in your own room, being able to talk on the phone, or keeping in touch with loved ones. On any given day, 90 to 100 people live in this facility, and they all need help with these things. It could be that they need someone looking in their ears to see if they need ear wax removed. They could need their hearing aid batteries changed, their tubing changed, or someone to put their hearing aids on for them.

Communication Facilitator

In the past, we have used the consultative model where an audiologist goes in once a month to do some of the higher-level tasks that need to be done, and they then train the staff who will carry on from there. However, that has never really worked. We have seen it not work over and over. We use a concept whereby we have a trained communication facilitator - purposely not talking about hearing.

This is not an audiologist. This is someone who might have an Associate’s degree, who has the right personality, who wants to be in people’s apartments with them to make sure they can hear their TV, their phone, and the smoke detector. This person wants to be in the public spaces and wants to get to know people and their backstories and help them communicate day-to-day.

As we have rolled out this program, we have determined that this does need to be a full-time person. We have someone in an assisted living facility all day, every day. At this point, the metrics show that this is making a huge impact on the staff, the families, and the residents.

The model here is that it is extending our services. An audiologist is the supervisor, and then you have a number of these communication facilitators throughout the system. We had success with this fairly quickly, and I will update you again when we have some final data.

Home Health/Hospice Care

Home health and hospice patients can no longer get to us. Is there a way for them to access our care? We are toying with of teaming up with OTs who could be doing this kind of assessment, as they are meant to be in the homes assessing daily functional activities. Generally though, they do not look at whether the person can use the phone, enjoy the TV, et cetera. This can be done under a supervising audiologist, who can also determine in which situations we should intervene, but they do not have to be the ones who are trying to go into every home, as we are not set up well to do that yet. We have colleagues who are. We have not gone down this path very far, but I wanted to mention that, as it is one more thing to think about pursuing.

Question & Answer

How would you recommend creating a framework for your team?

I think it depends on what already exists. Gerontologists work daily with people with hearing loss, yet they often tend to not think about hearing. You may find that they already have fairly well-defined interprofessional teams with other kinds of care, such as pharmacy, PT and OT. You want to bring some of these data and insinuate yourself into those teams. Chances are if you are at a hospital, some of those teams exist; you just have not been invited to be part of it. Very quickly, if you can get yourself there, they see the value. It is also cost effective. It is not expensive to do that. I think that is the place to start.

Where are your assisted living facilities?

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center is an integrated financial delivery system (IFDS). This is how we are going to cope with the Affordable Care Act. This big system will have its own insurance. Every program you create has to be able to go system wide. That has been an interesting push for us as audiologists. The three assisted living facilities are associated with a larger University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. We have a number of independent living and skilled nursing facilities. The concept behind this program is that we will go system wide with it once we have defined it in this one place. Certainly, wherever you are, it does not have to be part of your medical center. You could reach out to anyone in the community.

Have you infused the listenaiders into any other areas like the ER, or do you have them available on the floors? Have you used them in the assisted living facility?

I have been here for 25 years, and we have historically left piles of listenaiders on the different floors and in the ER. We have found that they consistently get lost. That is not a big deal in terms of the cost. However, I think we have enough nursing and staff turnover that it has never seemed to work.

What seems to work is having an easy consult system. They consult us, and then we deploy. We do talk calls. We consult during the day and go over to the floor. It used to be standard that they needed a hearing test, and then we would give them a listenaider. However, we are trying to get over ourselves as audiologists and say they do not need a hearing test if they do not want one. That is not why they are here. They just need to communicate. We are foregoing the hearing test and providing the listenaider instead. We always follow up the next day to make sure everyone knows how to use it. We would like to leave stacks of these, especially in the ER, but it generally has not worked.

References

Bartlett, G., Blais, R., Tamblyn, R., Clermont, R. J., & MacGibbon, B. (2008). Impact of patient communication problems on the risk of preventable adverse events in acute care settings. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 178(12), 1555-1562. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070690

Grabois, E. W., Nosek, M. A., & Rossi, C. D. (1999). Accessibility of primary care physicians' offices for people with disabilities. An analysis of compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act. Archives of Family Medicine, 8(1), 44-51.

Hoffman, J. M., Yorkston, K. M., Shumway-Cook, A., Ciol, M. A., Dudgeon, B. J., & Chan, L. (2005). Effect of communication disability on satisfaction with health care. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 5, 221-228. doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2005/022)

Lawthers, A. G., Pranksy, G. S., Peterson, L. E., & Himmelstein, J. H. (2003). Rethinking quality in the context of persons with disability. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 15(4), 287-299.

Lin, F. R., Niparko, J. K., & Ferrucci, L. (2011). Hearing loss prevalence in the United States. Archives of Internal Medicine, 171(20), 1851-1852. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.506

Sanchez, J., Byfield, G., Brown, T. T., LaFavor, K., Murphy, D., & Laud, P. (2000). Perceived accessibility versus actual physical accessibility of healthcare facilities. Rehabilitation Nursing, 25(1), 6-9. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2000.tb01849.x

Taylor, B., & Tysoe, B. (2013). Interventional Audiology: Partnering with physicians to deliver integrative and preventive hearing care. Hearing Review, 20(12), 16-22.

Cite this Content as:

Palmer, C. (2015, September). Interventional audiology: when is it time to move out of the booth? AudiologyOnline, Article 15226. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com.