Editor’s Note: This text course is an edited transcript of a live seminar. Download supplemental course materials.

Introduction

The essence of this topic is about relationship building with parents to ensure that students who are deaf or hard of hearing have an education of excellence. Thank you for this forum and opportunity, I think it is a fantastic way for us to all come together.

I do not know if any of you ever saw the old TV commercial with the actor who says, “I am not a doctor, but I play one on TV.” As I began to prepare this presentation, I had to be clear within myself about the perspective that I am sharing with you today, which is the perspective of a parent. I am assuming that most of you are audiologists within the clinical setting or the school-based setting. I know that you are the experts in your area of your responsibilities. Today's presentation is from my perspective as a parent. I have done this presentation before and was able to co-present with another audiologist. I am sure you are probably never supposed to apologize up front for a presentation, but if there are pieces in this presentation that leave you a bit wanting, it might be because not all the perspectives are necessarily shared. I am going to take you through the relationship of parents with their clinical and educational audiologists from the parent's point of view.

I am going to start with giving you a summation of our family story. Our children are no longer children; they are young women. It is a great season of life to be in. I enjoy being able to tell our story. It should be mentioned that my 21-year old daughter Sara, who I will be talking a lot about, is really the keeper of the story. If she were here today, I am sure at some parts, she would say, “Mom, that is not necessarily how it happened.” However, she has given me permission to talk. The other perspective I will be sharing with you is that of an advocate. I have been to almost 50 individualized education plan (IEP) meetings with other families who have children who are deaf and hard of hearing over the years. I have learned a lot about what it feels like for families, across the spectrum of degree of hearing loss and mode or method of communication, to be sitting in a room, fighting desperately for basic support services for children who are deaf or hard of hearing.

I wanted to give you a bit of my professional background. I always feel the urge to put air quotes around the word “professional,” because I am a professional as the Executive Director of Hands and Voices, but in terms of my background in the field of deafness, my true credentials are as a mother. My daughter Sara's favorite quote is, “Mom, you wouldn't have a job if it wasn’t for me,” which is completely true. Even though my daughter is grown, I still always come back to thinking that one of the biggest things I have to offer you as a professional is our family story and those of other families. I have been involved systemically in different areas over the last 15 years in the medical field, educational field, and the community.

We are so proud of Hands and Voices. We have grown from one chapter in Colorado in 1997 to over 50 chapters around the United States, Canada and abroad. You can go to our Web site (https://www.handsandvoices.org) and click on your state to find information about your local chapter. A couple years ago I also finished a certificate at the University of North Carolina in the area of leadership development. Currently, I am working on a book from Hands & Voices that will be released in June on Educational Advocacy for Students who are Deaf or Hard of Hearing. It has been co-authored by our former Executive Director, Leeanne Seaver as well as by Dr. Cheryl Deconde Johnson, who is the author of the book Educational Audiology Handbook (DeConde Johnson & Seaton, 2012). I have learned so much from her, and I am really glad to be part of that.

When I present, I like to share this quote from physicist Enrico Fermi who said, “Before I came here, I was confused about the subject. Having listened to your lecture, I am still confused, but on a higher level.” This presentation will take a few different twists and turns, but I hope you will walk away with a clearer understanding of how to navigate the educational system for our children from the parent point of view. Also, we are going to go through a few of areas of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA; 2004) today. Particularly, I have found that clinical audiologists do not always have a clear sense of what the law actually says in regard to audiology services. We will be going over that in a basic way. As I said, there are some of you who are more expert in the obligations and responsibilities of educational audiologists in your field. We will end our time together today thinking about how private audiology services, public audiology services and parents can work together effectively.

Before I get into my own story with Sara, I want to touch on my experience as an advocate, participating in the IEP with other families. There are times when I have been in IEP rooms, and I amazed at what goes wrong. I was working with one mother who was very frustrated because she could not seem to make any in-roads with the school team for her daughter. When the daughter was in preschool, if the hearing aids happened to fall out or her daughter took them out, the teachers’ protocol was to put the hearing aids in a plastic bag in her backpack for the rest of the day. This meant of course that her daughter was without hearing aids on those days. You might think that I am making this up, but I am not. You have to ask who and where are the experts surrounding both the teacher’s need for education and the family's need for support in order to accomplish such a basic task as ensuring that hearing aids are staying in a student’s ears?

Another story I would like to share is from a family who e-mailed us at Hands & Voices. It was January and the mother had just been informed that the boot for the FM system on her son’s hearing aid was the wrong one, and he had been wearing it since September. Since he was wearing the wrong FM boot, there was absolutely no way that he had had access to the FM system at all for four months since school had started. I did not share those stories with you to say that all services in schools are bad. They are just examples of the importance of what we are talking about here today. These issues go beyond the technology. It is about responsibility and accountability, both from families, users and IEP teams. Clinical audiology can support the families in the educational process, as well.

My A-ha Moments

Implications of Background Noise

I want to talk briefly about some of my a-ha moments in the world of deafness, and particularly around the use of technology in the classroom. When our daughter, Sara, was identified at the age of two with a moderate hearing loss, she was aided and began to make language and communication growth over a period of time. She was in a center-based preschool program for children who are deaf or hard of hearing. I had just begun my work with Hands & Voices in providing support. A parent called me one day and said, “We are considering building a 6-foot berm in the front of our yard. What do you think about that?” I was wondering why she called me to discuss gardening when we are a support organization for deaf children. She began to talk about her understanding of background noise and that they lived right in front of a busy highway. She was concerned about the implications of background noise with her daughter. That was a point in my life where I remember thinking, background noise? What does that have to do with anything? At this point, Sara was probably three or four years old, so we were two years into it. I am not saying our audiologist and interventionist never talked to us about noise; I just do not remember having a sense about it, either theoretically or in my day-to-day life with her. I had not quite realized implication of background noise.

As we were moving forward in years working with Sara, I knew I had to have an understanding of the technology and processes in order to support the expectations and recommendations of our school’s IEP team. In those days, and this will date me a little bit, the FM system was a box that was strapped to the front of Sara's chest. When I went into the preschool room, the audiologist was talking about the importance of using the FM system and I was completely against it. It was too much of a physical indicator at that time of my feelings towards Sara’s hearing loss, and I did not have any support at all for the team to use the FM system. It was then that our school district audiologist took me into a sound booth and said, “I just want to show you a little bit of testing and what Sara hears in noise and without noise.” I walked out of that booth changed for the first time in my life. I begin to understand that Sara's hearing loss was not static, that what she might be hearing sitting in a quiet space, close-up with the teacher was completely different than in noisy classroom. The implications of background noise was one of the a-ha moments in my life that I needed. I will talk more about how I became not just a supporter of recommendations, but also as an advocate of increased services for her through understanding that.

Being able to understand and realize what Sara's life was like in the classroom compared to at home was important also. I have a vivid memory of standing outside the kindergarten room with other parents waiting for children to come out of the door as the bell would ring every day. The bell would ring, the door would burst open and all the children would come running out of the classroom, meeting their parents. I have this clear image of Sara walking out the door with her jacket half off, practically dragging her way out the door. She was so exhausted. This came with an understanding of the work that she had to do every day to be able to be successful in the classroom and the implications of fatigue. All the way through high school, she would come home after school and just take a quick nap on the couch. Those are just a couple examples of my need as a parent to really understand what Sara's life was like in the classroom and not just in the home setting. This is a really important thing for audiologists to know, whether you are a clinical audiologist or an educational audiologist. We will talk more on the importance of knowing that part of your work goes beyond working with students, to ensure that parents have a good understanding of that aspect too.

Advocacy Matters

Another thing I learned throughout the course of Sara’s education was this idea that advocacy matters and that no does not always mean no. There were times in her education when I had an idea and I was absolutely told, “No.” I learned advocacy from other parents. This is one of the most important features of our organization at Hands & Voices. Parents get empowered from learning from other families, not just by what the law says in the IDEA, but how you go about ensuring the integrity of a student’s education.

Social/Emotional Implications in the Educational Setting

In terms of educational audiology services, we learned quickly that it was not just about the equipment. There is a person attached to those hearing aids or FM system or cochlear implants, and if we do not take care of the considerations of that person’s social and emotional needs, then we are not addressing the whole issue.

Learning to Let Go

For me as a parent, I knew that other parents needed to become aware and become strong advocates for their children, but over the course of time, our children began to have a say in their own education. For parents, this is a time where we need to learn when to advocate, when to let go, and when to let our children be the advocate. I have this great memory outside Sara's IEP when she was in 10th grade. We always met with her general education teachers the day before school started so we could go over how to use an FM system and different things. I remember I was standing outside the door with the teacher of the deaf, and we were kind squabbling a bit about who would take the lead in educating the teachers for the next day. I cannot quite remember, but I believe the teacher was saying, “Why don’t I go ahead and talk about what they need to know. Then you can.” I think I said, “No. I’ve got this. Let me do it.” We go in, and as we are sitting down, Sara starts the conversation by saying, “I just want to thank everybody for coming today. I am going to go ahead and pass around the FM system. I would ask that you try to clip it on so you know how that feels.” All of a sudden, I realized it was not the teacher of the deaf’s role to be an advocate in that moment, nor was it mine as a parent; it was really Sara's job to be an advocate for herself. That is the end goal that we want. It is not just for all of us in the circle of the three P's to feel good about our relationship, but ultimately that our children emerge as strong advocates for themselves.

Know Your Child

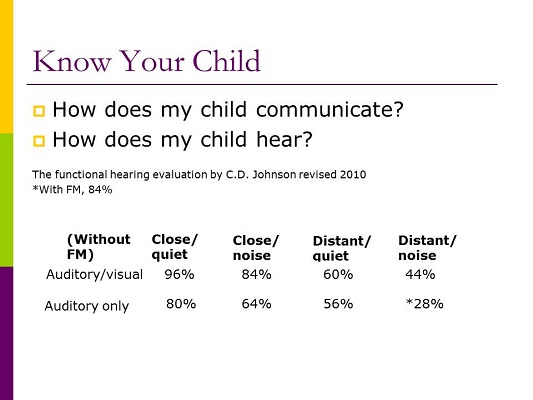

The functional hearing evaluation was one of the moments in IEP and educational services that served us well in being able to understand and explain the types of services Sara needed. You would think that the end result from the evaluation would be to determine her technology needs, but what it did was open the door to IEP conversations. From that day forward, I used the chart from the evaluation to describe Sara's hearing. Figure 1 shows Sara's chart from first grade. It includes her word recognition scores in two conditions - auditory/visual and auditory only, presented close-up in quiet, close up in noise, from a distance in quiet and from a distance in noise. In quiet from close up, she scored 96% in the auditory/verbal condition. This was our experience most of the time outside of school. People would always say to me, “You would never know she has a hearing loss. She does so well.” I used to think the same thing. But, if you apply these results to the typical noisy classroom situation, you see that close up in noise her score drops off to 84%. And, when you move eight feet back in quiet, her score drops to 80%. All of a sudden you understand why distance makes a difference. Then, when tested at a distance in noise, her score dropped to 28% without FM.

Figure 1. Sara’s speech perception scores in quiet and noise for auditory-visual and auditory-only conditions.

For Sara, we had never really measured the impact of speech reading until now. When the tester put her hand up over her mouth, you could see how much further Sara's scores dropped. When the tester measured speech perception in distance-with-noise and without access to the speaker, her score was 28%. I remember thinking I might as well not even send her to school if she is only going to get 28% of what is going on in her world every day. With the FM system, her score went up to 84%. I love this chart because it was numbers on paper that helped us to discuss what types of supports and services Sara might need. Will charts necessarily determine placements in schools, the use of sign language or not, or technology choices? No, not necessarily. There is no one particular answer, but for each individual student, the solutions for how to create communication accessibility must be explored.

I know a family who, at this point in their child's educational career after getting information like this, advocated strongly for physical environmental changes and acoustical accommodations to reduce the reverberation in the classroom. In our case, we began to explore the idea of using sign-language interpreting services for Sara, which was atypical in some ways at that time, because her primary mode of communication was speaking and listening. I will not go into that story today, but I will say that this assessment around the functional use of her hearing through technology was an impetus that opened my eyes to consider that I could not drop my daughter off at school with a hearing aid, add an FM in the classroom, and expect to have solved for all the influences of deafness in the classroom.

What Parents Want

What do parents want from their clinical and educational audiologists? An audiologist has knowledge about the basic systems that we have to navigate as families, including health, education, and insurance. Parents want an audiologist who can help them articulate the needs of their child out in the real world. This includes information, partnership, honesty, communication choices, amplification options, and discussions free from bias. At the very least, parents want an integrated perspective or someone who has an understanding of where other people come from who have something to say about the journey in deafness, whether it is the medical field, deaf and hard-of-hearing adults, or other parents and educational professionals.

I have a friend who has a profound hearing loss. I remember she offered to go in and just sit in Sara's classroom and observe what it was like. At that time my friend had hearing aids, but I think she has a cochlear implant now. This was when Sara was younger. It was so helpful to have someone else think about what sounds were going on in the classroom. There were things that I had never even thought about, such as in the summer when it's very hot and the teacher puts the fan right next to Sara's desk. My friend also told me that when she was in third grade, she remembers being in the school bathroom with her feet up hiding from her speech therapist. She said, “I do not remember any of the school projects that I did in elementary school, but I remember my speech therapy.” That simple statement made me remember that my daughter, while I needed to fight ferociously for communication access in the classroom, is also a child, and she has a right to live a child’s life.

When we explore various perspectives today, think beyond the three Ps to other perspectives, such as that of the general education teacher. If we do not take in this perspective into account, including the teacher's life, experience and outlook of having 28 children in her classroom, we will not be able to successfully advocate for the needs of our students. It is important to have the idea of integrated perspectives.

Basics of Special Education Law

We are going to spend the next few minutes going over some basics of Special Education laws. Educational audiologists may know these really well. If you are clinical audiologist, you may or may not be as well-versed in these sections of the laws. There are many good resources available, as I mentioned before. I have Dr. Johnson's Educational Audiology Handbook (2012) is one of them. It is on my desk and refer to it often.

When we talk about the law, I always like to start with IDEA. It is the law that provides the support for students who have a disability by reason that there is also an impact to the educational process. Having a disability does not necessarily make you eligible for special education services. There also has to be in an impact of that disability on education. We are not going to talk about eligibility today, although that is an area where parents often need support from a clinical audiologist.

I like to ask, “What is the purpose of IDEA?” We get so bogged down from year to year thinking about the about goals, objectives and related services such as audiology in the IEP, that we sometimes do not lift our head up and say, “What is all this for?”

From IDEA (300.1), the purpose includes: To ensure that all children with disabilities have available to them a free appropriate public education that emphasizes special education and related services designed to meet their unique needs and prepare them for further education, employment, and independent living" (Authority: 20 U.S.C. 1400(d)).

Another context to consider for IDEA is not just that students are eligible for special education, but to what extent and how much are you going to be able to get? We talk about that in context to FAPE. If you have ever heard of that acronym, it is free and appropriate public education. I think the term “appropriate” is a subjective term, and that we as IEP team members, parents, and other support professionals should determine what “appropriate” is for an individual student. Given that there is one law that covers the entire nation, and of course every state has individual state laws that support the national IDEA, you would think that we would all be on the same page. It would seem that you could go from district to district or state to state and basically see the same kinds of services provided for students.

That could not be further from reality. I can tell you I go to IEPs with families in one district where the use of FM system is never up for question. They provide them for all students who are deaf or hard of hearing. Then I will visit the district next door and they have this line in the sand where you cannot imagine how hard it is to get an FM system. This is why parents need to be such strong advocates and understand the definitions in the law. The “how” you get things is not always black and white. Your ability to be able to define and advocate for what is appropriate for your student plays a big part.

Chevy versus Cadillac

When I started going to IEPs, people used this expression all the time. They would say, “We would love to be able to provide a soundfield system or an FM system or captioning on TV for your student, but the law only says that we have to provide a Chevy; we do not have to provide a Cadillac.” I always wondered where people got this analogy? It actually is in the Rowley case from the Supreme Court. That was probably the case that set the basis for what FAPE is in special education. In the writings, one of the Supreme Court justices talked about the Chevy versus Cadillac idea, so that has taken hold when parents are being denied a service for their student. They are told, “Chevy versus Cadillac.” I love the family who was in a meeting where the district said, “Gosh, we wish we could provide that for your student, but we are only required to provide the Chevy.” She said, “That is fine. Go ahead and give my child a Chevy. Just please put an engine in it so that it works.”

Assistive Technology Requirements

Now we are going to talk about the assistive technology requirements. I find this section very interesting because you read in section H, “supporting the development and use of technology including assistive technology devices and assistive technology services to maximize accessibility for children with disabilities.” We as advocates found this very interesting language, because IDEA always uses the term “appropriate.” With regard to assistive technology, we are aiming to maximize accessibility. We think that is strong language and can be used in IEP. For hard-of-hearing and deaf education services in schools, it is important to know that there are other components and considerations in IDEA for deaf and hard-of-hearing students, but today we are going to talk about assistive technology and services, and proper functioning of hearing aids and cochlear implants.

There is a whole section in IDEA supporting giving parents training in order to be effective supporters in their child's education. I think that is important to bring up. We are not going to be covering other areas today, but there are areas in IDEA that go beyond assistive technology needs for deaf and hard-of-hearing students. Having said that, here is some basic information about what the definition of assistive technology is. “Assistive technology device means any item, piece of equipment, or product system, whether acquired commercially off-the-shelf, modified, or customized that is used to increase, maintain, or improve the functional capabilities of children with disabilities (34CFR 300.5).” In the 2006 regulations, this was added in the definition section, “The term does not include a medical device that is surgically implanted or the replacement of such device.” I do not have time to go into the complete history of how and why that language was added, but prior to 2004’s reauthorization, some case law had come down around the country where judges were finding that schools were required to do mapping of cochlear implants under the definitions in the IDEA. It was a big controversy. Since then, that language has been added.

At Hands & Voices, we were very interested in that topic as parents. We have the definition of what an assistive technology device is in the previous section. Assistive technology service means any service that directly assists a child with a disability in the selection, acquisition, or use of an assistive technology device. The definition contains evaluation, including functional assessment, providing the acquisition of the device, selecting the device, coordinating use of other therapies, interventions or services with assistive technology, training, technical assistance in use of device, and training for professionals. These are important for you to understand and know. An example would be when a family called us and said, “The school district’s FM unit broke down, and they are asking us to pay for the repairs. Can they do that?” When you go back to what FAPE is, free and appropriate public education, no they cannot. Sometimes if you are in that situation, you might want to say, “Well, let's pull up what the law actually says about this.”

The law also includes routine checking of hearing aids and external components. One of the jobs in the educational setting should be routine checking of hearing aids. The thing to think about here always is Who, What, When, Where, Why and How. Who is going to be responsible for checking the hearing aids? If it is the general education teacher every morning, has she had the training in order to ensure that it is working properly, or if the boot is the wrong one and has never worked for four months?

As a side note, if you are working with students, as they are getting older, you need to consider if they have the necessary information about how and who they need to contact when equipment is not functioning properly. When Sara was in ninth grade, I got a phone call from our educational audiologist at about 6 pm. It was a message on my machine and she said, “Hi Janet. Could you give a message to Sara? I really appreciate her calling to let me know her FM system isn't working, but please tell her that in the future, she could leave just one message. She does not need to leave 12.” Apparently Sara had called the school district audiologist several times that day. Of course my response was, “Yes, absolutely I will talk to her,” and internally I am saying, “I love that my daughter is a strong advocate and knew who to call when something was not going well.” I have heard so many stories of families waiting literally months for repairs on assistive technology. I will tell you that in Sara's case, the audiologist came out to the school the next day. Maybe she would have even without 12 messages, but I like the idea that my daughter was a strong advocate.

The section on assistive technology includes language on functional use, i.e. "The evaluation of the needs of a child with a disability including a functional evaluation of the child in the child's customary environment" (Assistive Technology 34CFR300.6(Part B) & 34CFR303.13(b)(1)(i)(Part C). It is not just about the equipment working, but how it is functioning. You have to consider noise, reverberation and acoustics. There is an old little booklet entitled Our Forgotten Children: Hard-of-Hearing Pupils in the Schools (Davis, 2001) that I used it a lot in the early years with Sara because it truly helped me advocate for needs of students who are hard of hearing. It has a nice graphic that describes the impact of noise and reverberation that I would share with other people.

There are a couple of other things to mention in the IDEA. Often, schools will deny a family being able to take home technology. It actually says in the law that on a case-by-case basis, if you can show that in order for the child to receive FAPE, they can use it at home. We brought the FM system home from school for one year in particular. We made the point that communication accessibility outside of school was important in literacy development. We wanted to a test using FM in the car and different places like that. We were able to get that through the law.

Understanding and Exploring the Relationships Between the Three Ps

Let's explore the relationship between the three P’s: parents and students, educational providers, and private or clinical audiology. In general, the role of the clinical audiologist is in the diagnosis of hearing loss, medical management and habilitation with hearing aids. Educational audiology focuses on the implications of hearing loss for educational management, access to the learning environment and assistive listening devices. I know there is crossover in both of these areas. In terms of collaboration between private and school-based professionals, some of the issues that come up are communication, different practice perspectives, roles, and privacy laws such as HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) and FERPA (Family Education Rights and Privacy Act). Furthermore, professional standards of practice may differ for educational audiologists under the auspices of the IDEA versus clinical audiologists. Time is probably one of the biggest barriers to a three-P relationship.

In terms of HIPAA/FERPA confidentiality laws, in my experience when parents give permission for professionals to communicate, that usually takes care of it.

Potential solutions for these issues stem from an opportunity to understand the common goals and shared advocacy across these three P’s. Communication should be consistent, written, and open, and it should be with parental support.

How Audiologists Can Help

Here are some things clinical audiologists can do to help. First, you can encourage parent involvement in their child's educational process. I would say that parents are all over a continuum of both their ability and knowledge-base to be meaningfully involved. Some families, because of their hierarchy of need, may not be able to memorize the IDEA and be super strong advocates. In other words, maybe their main concern is getting food on the table and not hearing loss. Whatever level a parent is at, I have always seen in my work at Hands & Voices that when you give families support information and modeling, they move up the learning curve. I have met parents before and asked, “What is the degree of your child’s hearing loss?” and they cannot articulate that. They do not know what degree of hearing loss their child has. In order for parents to be meaningfully involved, they have to have a good knowledge base. It is important that you, as audiologists, help families understand their child's hearing ability in a functional way; it is not enough to read the audiogram. They have to also understand the impact of hearing loss on their child's world. It is true that lending your expertise as parents prepare for IEP meetings is helpful. You may not have time to go to IEP meetings, but if a family brings an issue up to you, you might say, “When is your next IEP? Why don’t you bring your IEP into the next meeting and we will go over the sections.” Perhaps you will have some input for them.

I think the continuum of expertise and availability of educational audiology across the country is diverse as well. In some places, you get really strong audiology support in the school-based setting and in the IEP meeting, and then in other places it is almost nonexistent. Your role as a clinical audiologist may be very important, yet in other places it might just be supporting and saying, “Yes. They are getting it right over there at the school district.” Review with the parent the student needs at school. How is it going at school? What is going on? Have you had the opportunity to be in communication with the educational audiologist if the student has one? If you complete an audiogram, make sure that that is sent over to the school district. Review and recommend assessments. Although you cannot write a prescription for an IEP, you can write a letter of recommendation, and you can put in all the indicators of why the student needs an FM system. You cannot mandate it from the clinical point of view, but I think you could actually make or break the chance that a student receives technology through your expertise.

In terms of attending IEP meetings at the parents’ request, think about being in a room where there are maybe one or two parents, sometimes an advocate or a family friend, and maybe 10 to 15 school personnel. When parents are in a situation where they do not feel like an equal partner in the process and issues arise where the team is not able to come to agreement on something, the imbalance of power in a room is very difficult to overcome. When the family brings an advocate or a professional who works with that student, the expertise of that can change how the meeting goes. If you are ever in a situation where a family is really struggling, besides helping them clinically, it would probably be interesting for you to see what an IEP meeting looks like.

I will discuss reasons why a parent might ask a private provider to attend an IEP. You have a unique expertise and knowledge of the student, and you could add to that body of knowledge that the team can use to determine services. You are not constrained by the political elements of the process. I always try to say this in a way that is not disrespectful. I tell this through a story. I was meeting a family as an advocate to go with them to the IEP. I arrived early. I thought the family was already in the room. I walked in and there were a lot of people at the table. It turned out to be the pre-meeting for the IEP, which schools are allowed to have. The district administrator did not know who I was. I think she must have thought I was a professional. She said, “Come on in and sit down.” While I am sitting down waiting, she is dictating to the team what they can and cannot say in IEP meeting when it starts, and what they will or will not agree to in terms of support and services. This is supposed to be determined by the entire IEP team based on individual needs of the student, and this was a situation where it was definitely about the money. They did not want to agree to certain things because of the money it would cost. When we talk about the constraints of the political elements, sometimes the school district audiologist is literally putting her job up at risk by speaking up. I will tell you I have seen audiologists do that. I was not risking my job that day as an advocate. It is such a good feeling to see people who really stand up for the needs of students.

Sometimes you hit “hurdle talk” in the IEP process, and you want to maintain focus on the needs of the student. At Hands & Voices, what we call hurdle talk is when you are talking about the need for an FM system and you will get a response about something that has nothing to do with the conversation such as, “You know I have 500 other students in this building that need my attention.” We call that hurdle talk. Sometimes you are not getting reasonable responses to the request, and bringing in an expert can sometimes help stay better focused on the topic.

I have found, more often than not, the educators and people at the table might be under some political constraints. Sometimes they will run out to the parking lot after and say, “Thank you so much for coming. I couldn't say that, but I am so glad that you were there to say it.” You can help others understand the needs of the student, and make sure everyone is on the same page with technology issues. For instance, the clinical audiologist who is fitting the personal hearing aid might want to communicate with the educational audiologist to make sure that the FM that is ordered will be compatible together. It is also a learning experience for clinical audiologists to understand some of educational implications that the student is facing and to interpret assessments.

The culture and the constraints of the educational system can be shocking. You will be in for a surprise if you compare what the law actually syas compared to what happens in reality, and it will help you understand the constraints of the educational audiologist. Also, as a clinical audiologist, you may be getting information from a parent that may not have full knowledge of the law. One important thing to do is connect that family to resources and parent-to-parent support groups. On our Web site at Hands & Voices (https://www.handsandvoices.org/), you can go to the Resources section and find a technology section. It is mostly written by parents, and explains what the law supports, what rights you have as a parent to participate in the IEP process, and some basic technology issues that come up for families.

Parent Involvement

It is important to meet parents on their terms. Parents need to be able to tell you when they are ready or when they are not ready. Meeting parents on equal terms is very important. Parents do sometimes need counseling and training, and that is a related service under the IDEA; you can seek for an advocate in the IEP process. Seeking and maintaining parent participation is crucial, especially as their children get older. I can say this now as a parent of three in their early 20s, as you are winding down your daily parenting years, you do not always stay quite as in touch as you did in the beginning. Parents do need to maintain a presence and participate even as their children get older.

Another issue that can arise with parent involvement is communication challenges with families who are Deaf and non-English speaking. Potential solutions for issues that arise with all parents and families include providing training for school staff on the importance of the parents’ role, provide training for parents on ways they can support their child’s IEP goals, provide training for parents to develop leadership skills and mentor other parents, and create a paid parent liaison position to create parent-to-parent activities.

What parents need are a basic understanding of audiology and impact of hearing loss. We need to understand our children's experience from their point of view. I think sometimes, particularly for children who seem to be “doing really well,” we do not always quite understand what their day looks like and what their needs are. We learn the child's point of view from our parent community, from Deaf and hard of hearing adults or role models, from professionals, both public and private providers, and from our children. It is a learning curve for parents. It is something I learned over time from many different people. We learn that with an open mind.

Our motto at Hands & Voices is what works for your child is what makes the choice right. The idea of what we need to consider moves from what we want for our children to what they really need. I met a family last month whose daughter was late-identified with a hearing loss at the age of 8. They were at the audiologist to get fitted for hearing aids, and the dad just could not get over the idea that she needed them. She had a mild hearing loss, and he was not convinced. At that point, it was new information and knowledge they were learning. It was hard for him to think in context about what he wanted versus what his daughter really needed. That is something we learn through the support of the good professionals in our lives.

My New Teacher

I would like to close with my reflections on where Sara is today. She utilized hearing aids throughout her life. She has used an FM system on and off. When she went on to college and they no longer had IEP meetings, I could not believe that I was not part of that anymore. She was in control of her communication accessibility in the classroom and did use the FM system a bit in the classroom setting, but she was able to navigate and negotiate communication accessibility in very creative ways.

I am going to close today with the story of Anna. When Sara was in high school, I loved that her teacher of the deaf did not ask Sara what she could do for her; instead, she asked Sara to start giving back in her life. Sara began going over every Wednesday morning to a classroom with a young student named Anna who wore hearing aids. Sara would come home and I would ask her how it went. She would say, “I don’t know. I just don’t think I am really doing that much for her.” But she went every week and liked it.

One day Sara came bursting through the door, and said “Mom, you'll never believe it.” Sara said she walked into Anna’s classroom and she looked around. Sara said to the teacher, “Is Anna sick today? Where is she?” The teacher looked at Sara with a funny face and said, “She is right over there at her desk.” Sara looked back, and there Anna was sitting. Sara had not recognized Anna because, through those months, every time Sara had gone into the classroom, Anna always had her hoodie up. She was so ashamed of her hearing aids. But there was Anna sitting at her desk with a huge grin on her face looking at Sara with her hoodie down. Sara had been going in week after week just encouraging Anna not to be ashamed of her hearing aids. She should always be proud. Sara always wore her hair back. The idea that Sara had made an impact in another child's life, to me, was a story that came full circle.

As parents and professionals supporting our students through school and for an education of excellence, seeing our children emerging and being able to give back is wonderful.

Questions and Answers

Do you think hearing aids should be considered assistive technology if the child has a determined need, but no financial means to obtain them?

Yes, I do. Under the IDEA, hearing aids are considered assistive technology. I think the basic question you are asking is, “Are school districts obligated to buy hearing aids?” It is a gray area, honestly. It also could be considered a personal device under durable medical equipment, but if there is no financial means to get them, yes, it does fall under IDEA that the hearing aids should be purchased by the school district. However, the caveats around that are that they are owned by the district. The district gets to choose which technology. We as parents and advocates have always understood that IDEA could pay for hearing aids for our children. We would say that is not the best route to go. In general, there is lots of support for getting hearing aids for children. I know in the state of Colorado, we have an extensive funding toolkit to help parents find funding. Clinical audiologists are usually really good at helping find funding. The answer to your question is yes, under the IDEA, it could be sought for the hearing aids to be paid. In the best of all worlds, I think there are more considerations than who schools be paying for them.

Are parents and the school both allowed to invite participants to an IEP?

Absolutely. It is very clear in the IDEA that attendees at an IEP are at the discretion of the parents and the school. Both are allowed to invite participants. Case law has supported this. If the parents want another party there, they can be there.

References

Davis, J. M. (2001). Our forgotten children: Hard of hearing pupils in the schools. Bethesda, MD: SHHH.

DeConde Johnson, C. & Seaton, J. B. (2012). Educational audiology handbook: second edition. Clifton Park, NY: Delmar.

U.S. Department of Education. (2004). Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Retrieved from https://idea.ed.gov

Cite this content as:

DesGeorges, J. (2013, June). The Three P’s: Enhancing a student’s education through private audiology services, public education audiology, and parents. AudiologyOnline, Article #11868. Retrieved from: https://www.audiologyonline.com/