Abstract

This paper details the development of a tinnitus evaluation software program that complies with the criteria set forth in CPT Code 92625. It also describes the contents of information obtained, including;insurance information, patient demographics, psychological scales, possible etiologies, medications, medical conditions, and quantitative measurements of frequency, intensity and masking level of patient's tinnitus. There is also a section of the software that is utilized to measure treatment effects obtained with a new ultrasound device. Several versions are detailed that can be used for different clinical preferences;some are more comprehensive than others and as a result collect more or less data and data collection time.

Development of a Tinnitus Evaluation Software Program

Introduction

Tinnitus is a disorder that has been described as hearing any sound or noise that is not externally generated. There are three diagnostic codes for tinnitus: a general category, tinnitus aurium, ICD-9 388.30; subjective tinnitus, ICD-9 388.31;and objective tinnitus, ICD-9 388.32 (AMA, 2008).

It is estimated that nearly one out of six individuals has some form of tinnitus (Henry, Dennis & Schechter, 2005). This translates to approximately 45 million individuals in the U.S. and more than 135 million individuals in Europe that have some degree of tinnitus.

While we know how many individuals in the general population are estimated to have tinnitus, little is known about the number of patients seeing a specialist (audiologist or ENT) that have tinnitus. A recent survey of more than 140 consecutive patients in my practice (Holmes, 2009) found that nearly 50% reported having some degree of tinnitus. This is higher than the incidence of tinnitus in the general population and may be attributed to the fact that patients visit an audiology practice due to hearing related problems, and tinnitus often co-occurs with hearing loss.

There have been numerous attempts to treat tinnitus (Ahmad & Seidman, 2004;Bartnik, Fabijanska & Rogowski, 2001;Davis, Paki & Hanley, 2007;Gold, Formby & Gray, 2000;Henry, Schechter, Nagler, & Fausti, 2002;Hilton & Stuart, 2004;Jastreboff & Hazell, 2004;McFerran & Baguley, 2008;Martinez Devesa, Waddell, Perera & Theodoulou, 2007). Anecdotal reports from patients indicate that physicians often tell their patients to "learn to live with tinnitus, because there is nothing that can be done to help it". While a discussion of the various tinnitus treatment approaches is beyond the scope of this paper, audiologists will frequently encounter tinnitus patients in their daily work and must make clinical decisions as to management. An efficient method of evaluating tinnitus can assist audiologists with defining the tinnitus, determining its degree, determining whether or not it is handicapping, identifying possible causal information requiring medical work-up, determining a baseline for treatment (regardless of treatment approach), and determining appropriate referrals, if indicated.

Billing

In 2006, CPT code 92625 was assigned for the assessment of tinnitus (AMA, 2009). There are three criteria that must be met in order to meet the minimum requirements as set forth in the guidelines. The following items must be measured: 1) frequency of the tinnitus, 2) the intensity of the tinnitus, and 3) the level that masks the tinnitus. Traditionally, we have been able to accomplish these criteria by having the patient listen to a signal (pure tone or noise) generated through an audiometer and ask the patient to respond whether the signal was lower or higher in "pitch" (frequency) than his or her tinnitus. Then, a bracketing technique is utilized with the octaves and half octaves available on our equipment (Hall & Haynes, 2001). The same procedure could then be applied for determining the loudness (intensity) of the tinnitus, by asking the patient whether a signal is louder or softer than his or her tinnitus. The step size may be limited by current equipment, which may be restricted to 1, 2, 5, or 10 dB increments. Once tinnitus frequency and intensity is established, masking can then be applied by increasing the intensity of the signal until the patient no longer hears the tinnitus. While this is generally possible in most audiology clinics, it is cumbersome and provides a rather gross estimate of the criteria for CPT Code 92625. Specialized equipment for tinnitus evaluation (tone and noise generators, filters, amplifiers, etc.) is readily available;however, the cost of such equipment is prohibitive for many hearing care practices.

Most practices, as a standard protocol, will collect a variety of patient information for all incoming patients, including insurance information, case history, current medications, and other health conditions. After the patient evaluation has been completed, the results of the patient's visit are then collated into a report for the medical chart and typically, for a copy to the referring physician. The final step is then to submit a bill to the insurance company for reimbursement. To be clinically useful, a tinnitus evaluation software program should acquire most of this information in an efficient and cost effective manner, and avoid duplicating documentation. The goal of a tinnitus evaluation software program would thus be to gather information needed for a complete evaluation including rendering a diagnosis and treatment recommendations, record the results in the medical record, and provide information to the patent's insurance for reimbursement in the most efficient manner possible.

Tinnitus Evaluation Software Program™ (TEP)

With this in mind, the research group at Melmedtronics, Inc. developed the Tinnitus Evaluation Software Program™ (TEP), that would: 1) meet the criteria for CPT Code 92625;2) gather insurance information for billing;3) collect patient demographic information;4) obtain historical information that may provide evidence of causation;5) review any medications that may contribute to tinnitus;6) review any medical conditions that may be responsible for tinnitus;7) evaluate for possible depression,(McFerran & Baguley, 2008), 8) evaluate for anxiety, (Beck, Epstein, Brown & Steer, 1988);9) quantify the extent of handicap caused by tinnitus (Newman, Jacobson & Spitzer, 1960;Handscomb, 2006) and automatically generate a report for the medical record.

In addition to the evaluation portion of the software, there is also a section for evaluation of treatment. This section was developed specifically to evaluate the effects of treatment using a new ultrasonic device. A 1-10 scale is used to determine pre and post-treatment levels of tinnitus, and can only be activated if the patient evaluated does not report any exclusion criteria for use of the ultrasonic device. The exclusionary criteria are presented, and if the patient answers YES to any of the items the software will not allow access to the treatment section. This was necessary to prevent patients with exclusions from inadvertently being treated. If a patient does not have any exclusion criteria, then he or she can be treated with the ultrasound device.

The results from the evaluation and the treatment sections are then combined into the Clinical Report and Letter of Medical Necessity. If the patient has positive results with the ultrasonic tinnitus device then the Letter of Medical Necessity can be generated and submitted to the patient's insurance for reimbursement review. For professionals who provide tinnitus treatment utilizing other methods, or who refer to others for tinnitus treatment, the evaluation portion of the TEP software can be used without utilizing the treatment section. In this case, the results of the evaluation can be saved, and an evaluation report generated.

TEP - Versions

The TEP is available in four versions: Research, Clinical, Express and Super Express (or Follow-up). The Research version is the most comprehensive and thus takes the most time to administer (approximately 30 - 40 minutes). Depending on the needs of the practice setting and/or individual patient, other versions of TEP can be administered. Each contains a sub-set of information included in the Research version, and time to administer varies accordingly. The Clinical version takes approximately 20 - 30 minutes to administer, the Express version takes approximately 15 - 20 minutes, and the Super Express/Follow-Up takes approximately 8 to 12 minutes. Figure 1 lists the components included in each version.

Figure 1. Comparison of TEP versions.

TEP Software - Intake and Case History Sections

The components included in the TEP that make up the background information, history and intake are:

- Patient Information (name, address, gender, date of birth)

- Insurance Information (insurance company, address, group number, policy number)

- Clinical History (description of tinnitus, duration, possible causes, vertigo, temporomandibular oint syndrome, surgeries)

- Health Conditions: Reviews 50 known conditions that sometimes contribute to tinnitus.

- Medications: Reviews 600 known medications that have been reported by some patients as having a side effect of tinnitus.

Figures 2 and 3 provide examples of the Clinical History and Current Health Conditions sections of TEP.

Figure 2. Clinical History section of TEP.

Figure 3. Current Health Conditions section of TEP.

Click Here to View a Larger Version of Figure 3 (PDF)

Tinnitus Handicap Inventory

TEP includes a section for determining the extent of handicap caused by the tinnitus and its severity using Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (Newman, Jacobson, & Spitzer, 1996). This section includes 25 questions that can be further divided into three sub-categories for research purposes. Each question is rated yes, no or sometimes. This results in a severity rating - slight, mild, moderate, severe, and catastrophic. Figure 4 is a screen shot of this section of the software.

Figure 4. Tinnitus Handicap Inventory section of TEP

Click Here to View a Larger Version of Figure 4 (PDF)

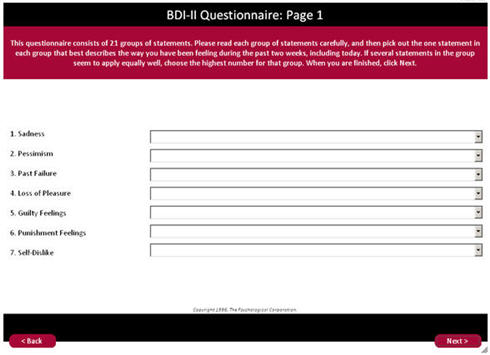

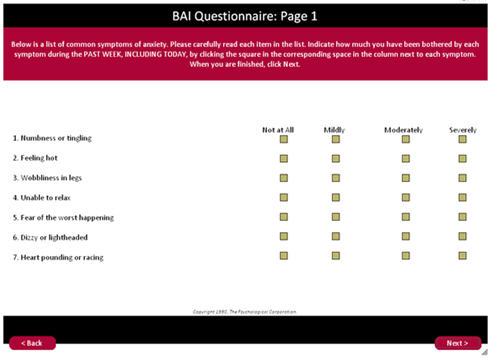

Beck Depression Inventory II & Beck Anxiety Inventory

Utilizing the Beck Depression Inventory II and the Beck Anxiety Inventory, this section of TEP attempts to quantify depression and anxiety, if any, caused by the patient's tinnitus using self-ratings. Both the depression inventory and the anxiety inventory contain 21 questions. Depression results are divided into: Non-Depressed, Minimal depression, Mild depression, Moderate depression, Severe depression. The Anxiety inventory results are divided into: Minimal anxiety, Mild anxiety, Moderate anxiety, Severe anxiety. These results can assist the audiologist in determining appropriate referrals and follow-up, and provide information regarding the overall impact the tinnitus is having on the patient's life. It can also be used pre- and post-treatment to help determine efficacy of treatment. Figure 5 and 6 are screen shots from the Beck Depression Inventory-II section of the software and Beck Anxiety Inventory section, respectively.

Figure 5. The Beck Depression Inventory-II section of the TEP software.

Figure 6. The Beck Anxiety Inventory section of the TEP software.

Click Here to View a Larger Version of Figure 6 (PDF)

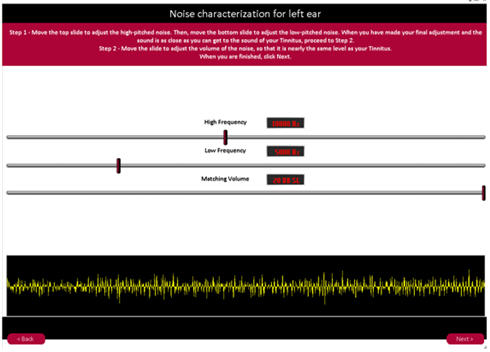

Characterization of Tinnitus

In order to characterize the patient's tinnitus, TEP includes the following sections: Identification of Type of Tinnitus;Establishing Sensation Level;Characterization of Noise;Characterization of Tone.

The Identification of Type of Tinnitus section uses a questionnaire format to assess both the quality and location of the tinnitus.

In Establishing Sensation Level (SL), threshold is established using a 750 Hz tone. This becomes each individual's threshold, to be used as that individual's 0 dB SL. All other signals, tone or noise are recorded in dB re: sensation level for the 750 dB tone threshold.

For Characterization of Noise, a match is established using a high cut filter and low cut filter. These filters are moved by the patient to approximate, as close as possible, the match of the "noise" tinnitus. Intensity is then matched after frequency band has been established, and results are given in dB SL. A screen shot of this section of the TEP software is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. TEP's Noise Characterization interface.

For Characterization of Tone, a sinusoidal tone is generated for a frequency match.

The patient moves a slide switch up and down in frequency until a best match is made with the tinnitus. The matching level is then determined in dB SL.

Report Generation

TEP generates an automated report for the medical record. The clinician has the opportunity to enter their letterhead information, clinic name, title and credentials. This information will then appear on every report generated after an evaluation has been saved to a file. All of the information in the report is based on the responses recorded during the evaluation. This saves time and helps prevent clinical errors as there is no need to duplicate or transfer results to another report. Once the file has been saved, the clinician can then print the report, place it in the chart, and/or send a copy to the referring physician.

Sample Report - Evaluation

Click Here to View a Sample Report (PDF)

TEP Availability

Professionals interested in using the Tinnitus Evaluation Program™ can download any or all of the four versions from www.tinnitustreatment.com. Signing up as a provider will generate a user I.D. and Password so that any of the versions can be downloaded to each of the computers in your clinic. There is no charge for the software for Audiologists, ENT physicians or Hearing Instrument Specialists.

References

Ahmad, N., & Seidman, M. (2004). Tinnitus in the older adult: Epidemiology, pathophysiology and treatment options. Drugs & Aging, 21(5), 297-305.

AMA, (2008). International classification of diseases. Physician Edition, ICD-9, Vol. 1-2.

AMA, (2009). CPT 2008 - standard edition.

Bartnik, G., Fabijanska, A., & Rogowski, M. (2001). Experiences in the treatment of patients with tinnitus and/or hyperacusis using the habituation method. Proceeding of the 4th European Conference in Audiology, Oulu, Finland, June 6-10, 1999. Scandinavian Audiology. Supplementum, 30, 187-190.

Beck, A.T., Epstein, N., Brown, G. & Steer, R.A. (1988) An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(6), 893-7.

Davis, P. B., Paki, B., & Hanley, P. J. (2007). Neuromonics tinnitus treatment: Third clinical trial. Ear and Hearing, 28(2), 242-259.

Gold, S., Formby, C., & Gray, W. h2000). Celebrating a decade of evaluation and treatment: The University of Maryland Tinnitus & Hyperacusis Center. American Journal of Audiology, 9(2), 69-74.

Goldstein, B. A., Shulman, A., Lenhardt, M., Richards, D., Madsen, A., and Guinta, R., (2001). Long¬term inhibition of tinnitus by Ultra Quiet Therapy Preliminary Report, International Tinnitus Journal, 7(2):122-7.

Hall, J., & Haynes, D. (2001). Audiologic assessment and consultation of the tinnitus patient. Seminars in Hearing, 22(1), 37.

Handscomb, L. (2006). Analysis of Responses to Individual Items on the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory According to Severity of Tinnitus Handicap. American Journal of Audiology, 15, 102-107.

Henry, J., Dennis, K., & Schechter, M. (2005). General review of tinnitus: Prevalence, mechanisms, effects, and management. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 48(5), 1204-1235.

Henry, J., Schechter, M., Nagler, S., & Fausti, S. (2002). Comparison of tinnitus masking and tinnitus retraining therapy. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 13(10), 559-581.

Hilton, M., & Stuart, E. (2004). Ginkgo biloba for tinnitus. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2.

Holmes, D. (2009). Incidence of patients reporting tinnitus in an audiology practice. Unpublished study.

Jastreboff, P. J., & Hazell, J. W. P. (2004). Tinnitus retraining therapy: Implementing the neurophysiological model. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lenhardt, M.L., Skellett, R., Wang, P., and Clarke, A. (1991). Human ultrasonic speech perception. Science, 253(5015), 82-85.

Lenhardt, M.L. (2003). Ultrasonic hearing in humans: applications for tinnitus treatment. International Tinnitus Journal, 9(2), 69-75.

Lockwood, A.H., Salvi, R.J., Coad, M.L., & Towsley, D.S. (1998). The functional neuroanatomy of tinnitus: evidence for limbic system links and neural plasticity. Neurology, 50, 114-120.

McFerran, D., & Baguley, D. (2008). The efficacy of treatments for depression used in the management of tinnitus. Audiological Medicine, 6(1), 40-47.

Martinez Devesa, P., Waddell, A., Perera, R., & Theodoulou, M. (2007). Cognitive behavioural therapy for tinnitus. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1.

Newman, C. W., Jacobson, G. P., & Spitzer, J. B. (1996). Development of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Archives of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, 122, 143-148.