This text-based course is a transcript of a live webinar. Please download and refer to the slide presentation that was used in the live webinar for all images, graphs, and references.

Introduction

My talk today is about an integrated approach to tinnitus patient management. I’m going to present this in an unbiased manner, as when it comes to therapeutic approaches for tinnitus, there is really no clear winner. There is not even one particular theory on the generation of tinnitus that we know to be absolutely the unequivocal answer. There is still a lot for us to learn. So I am going to try to present this using an unbiased approach and I will also give you my opinion, as those of you who know me would expect.

Tinnitus is a problem that most audiologists face on an almost daily basis. Not every audiologist needs to be a tinnitus therapist per se, but every audiologist needs to be able to present the facts to their patients with tinnitus. They can then mutually decide with the patient what the next steps would be, such as whether or not an outside referral is in order or whether the audiologist can provide the needed services.

Tinnitus Facts

Fifteen percent of the general population report tinnitus, and this number is surprisingly stable throughout the industrialized world. More than 70% of people who have hearing loss report having had tinnitus. Eighty to ninety percent of tinnitus patients show some evidence of hearing loss. Keep in mind, however, that the number of people who have tinnitus and have some damage to the auditory system may be even higher because the audiogram does not reflect damage to the auditory system until there have been enough hair cells affected. Thousands of hair cells can be impaired, which would constitute auditory damage, but you may not see anything on an audiogram per se. A very important statistic is this one: 10-20% of tinnitus sufferers seek medical attention. What that implies is that 80-90% of people who have tinnitus are able to naturally habituate to it and live with it, and that is going to be a topic that we will discuss in greater detail in this presentation.

Modern Theories of Tinnitus Origin

This topic could take up another several classes, so I will just touch upon some of the modern theories of tinnitus origin. When discussing tinnitus with your patients, you have to be able to present information that is based on evidence, and will give the patient some knowledge about why they have tinnitus. It is never adequate to say to a patient, “There is nothing we can do for you.” It is accurate to say that there is no cure for tinnitus, but it is completely inaccurate to say that there is nothing that can be done for them or that they just need to learn to live with tinnitus. Our job as audiologists is to be able to provide information to patients and then give them guidance as to managing tinnitus.

The most popular theory today is that tinnitus is a result of a disruption of auditory input. In other words, when there is any kind of damage to the peripheral auditory system, and really to the peripheral nervous system in any sense, it will result in a subsequent change to the central system. Take hearing loss, for example. If you have a high frequency hearing loss, there are changes that occur that create an increased amount of activity in the central auditory system. This has been shown very clearly by a number of researchers using imaging studies such as PET scans and fMRI. Studies on animals have found that when the central system is not receiving input, rather than shutting itself down and becoming less active, it increases its activity. This is particularly true in areas of the central auditory system such as the dorsal cochlear nucleus, the inferior colliculus, and also in the auditory cortex. For example, if you have high frequency hearing loss, the tinnitus perception will usually be located in the high frequencies. This makes sense because if you think about it, where does hearing loss begin? It begins in the outer hair cells, and the outer hair cells have an efferent function. If you have damage to the outer hair cells, then there may be a decrease in the inhibitory function of the auditory system and so what ought to be inhibited, this phantom signal, does not become inhibited. This also involves cortical plasticity, which was not even known about 20 years ago. What cortical plasticity means is that your brain is constantly changing and rewiring itself. We know about the tonotopic arrangement of the cochlea, and there is also a tonotopic arrangement in the auditory cortex. Certain areas of the primary auditory area respond to high frequencies, and other areas respond to low frequencies. If your cortex is not receiving stimulation from the cochlea, let’s say in the high frequencies, then those neurons responsible for processing the high frequencies in the brain are still intact, since the damage is in the cochlea. The neurons in the brain that are responsible for high frequencies will begin to take on some other function. Specifically, they will begin to respond to other frequencies, like the mid frequencies. This is what is happening with cortical plasticity, and in fact there will be greater representation for the frequencies right at the point where the hearing loss starts to drop. For example, if you have normal hearing until 2000 Hz, and then a drop at 3000 Hz and above, there is going to be more neurons in the brain responding to that 2000 Hz region than was originally designed. Again, the brain takes on a new function.

While the vast majority of people with tinnitus have hearing loss, there are other causes of tinnitus and other influencing factors as well. For example, a person who has neck damage, or a person who grinds their teeth at night may report tinnitus. In fact, some people with tinnitus can change the perception of their tinnitus by moving their jaw, or by even moving their eyes to one side or the other. Many people can change the perception of their tinnitus. This is because there is a lot of crosstalk between the nerves, or what is called ephaptic transmission. For example, if you have cervical damage, some of that signal that ought to be shunted to the somatosensory cortex can actually get short-circuited, if you will, over to the auditory cortex. If it reaches the auditory cortex, regardless of where it begins, it is going to be perceived as an acoustic event. Therefore, the signal that ought to be perceived as a somatosensory event or something that you feel actually becomes something that you think you hear. Again, this ephaptic transmission is very common. Some researchers say in at least 30% of tinnitus cases there are somatosensory influences. As audiologists, our patients often report that their tinnitus is at its peak when they first wake up in the morning. I think that this report may be not only related to the contrast between the silence of sleep and waking up with tinnitus, but it may also be related to their physical positioning while sleeping, i.e., how many pillows they are using, whether they are sleeping on their back, side, stomach, etc. There may be a somatosensory influence.

There are also collateral neurons that are called extralamniscal neurons, particularly in the dorsal cochlear nucleus, that go to the primary and secondary auditory area and receive input from the somasthetic system. Importantly, there is also a major association between fear and threat, and tinnitus. We are going to discuss that in greater detail in this presentation. If a person does not perceive the tinnitus as being of any importance, then the natural habituation process is much more likely to take place than when a person has a lot of negative emotions around their tinnitus. The longer you have tinnitus, the more areas of your brain become activated. There is a widely distributed gamma network (into frontal and parietal regions). Lastly, there is a recent important finding that has been published in the neurology journals, and that is, with tinnitus there may be dysfunctional gating in the basal ganglia or the thalamic reticular nucleus. We can explore this further in a case study.

Case report. The patient is a 63-year-old otolaryngologist who reported having tinnitus for about 40 years. He had a recent stroke, and recovered well. The stroke was located in the left hemisphere, in the more dorsal part of the corona radiate. It was involved in the body of the caudate and caudodorsal aspect of the putamen. Here is what is interesting about this. Fortunately, the patient recovered completely from his stroke with no damage to speech. His hearing also remained unchanged. The one thing that did change, however, was his tinnitus. It disappeared completely.

About the same time, one of my colleagues here at University of California San Francisco, a brilliant neuro-otologist named Steve Cheung, was doing some work on Parkinson’s patients with deep brain stimulation to try to control their tremors. He started with a cohort of six patients, four of whom had tinnitus and two of whom did not. What Steve found, remarkably, is that whenever he stimulated the caudate nucleus area right about the putamen, the four patients who had the tinnitus reported that their tinnitus was gone, and the two patients who did not have tinnitus reported that they were hearing something. By the way, the caudate nucleus is located in the area around the basal ganglia, and as you know, the basal ganglia really have nothing to do with hearing. What is remarkable about this accidental finding is that it suggests that tinnitus may be caused by factors completely unrelated to hearing itself. It may in fact be related to the integration of multisensory stimuli because that is what the basal ganglia do. There are areas around the basal ganglia including the nucleus accumbens that have strong reactions to stress and to emotional sensations. Steve published this study in Neuroscience in 2010 (Cheung & Larson, 2010).

The way Steve explained it, is that a gate refers to an area that would normally remain closed for a phantom perception, unless the gate is impaired. If the gate is impaired, it would allow the phantom perception to get through. When he stimulated around the caudate nucleus, it triggered the gate to open up. Of course the theory is much more complex than what I am describing here for the purposes of this course.

One month later, Josef Rauschecker and colleagues came out with another gatekeeping theory (Rauschecker, Leaver, & Muhlau, 2010). They talked about the gatekeeper as going through the medial geniculate nucleus and traveling through the thalamic reticular nucleus, which would evaluate whether or not the perception should be passed on to higher cortical areas. Remarkably, Rauschecker also found was a loss of volume in the medial prefrontal cortex in people who had tinnitus, and that the medial prefrontal cortex activates the thalamic reticular nucleus. He said that if the volume loss created a loss of neurons, both the medial prefrontal cortex and the thalamic reticular nucleus would malfunction, opening up the gate and allowing the tinnitus to be perceived by the person. This is a remarkable finding because this area is not related to the hearing mechanism. The medial prefrontal cortex is not really part of the classical auditory system.

Another finding that influences current theories of tinnitus has to do with tinnitus and EEG patterns. There is a lot of different electrical activity that is going in the brain. An alpha level or an alpha band is your relaxed level, your beta band is a more active level, and the gamma network is the most active level. A couple of interesting studies (Weisz, Moratti, Meinzer, Dohrmann & Elbert, 2005; De Ridder et al., 2011) have suggested that tinnitus may be highly correlated with these bands. For example, Weisz and colleagues found that there is not enough activity in the alpha band relative to the beta band in tinnitus patients. De Ridder et al. (2011) reported that for people who had tinnitus for less than 4 years, their gamma network, the fast-acting network in their brain, was predominantly in the temporal cortex. However, the longer they had tinnitus, the distribution of the gamma network started to go into the frontal and parietal regions. That is an indication that, over time, the longer you have tinnitus, more parts of your brain become activated by the tinnitus. We’ll discuss how this may impact our clinical decision-making later in this presentation.

Stress and Tinnitus

Baigi and colleagues (2011) published an interesting study on stress and tinnitus. They looked at 12,166 people, of which 2,024 had tinnitus. They wanted to find out which factor was more important – noise or stress – in moving someone from a situation where they just notice their tinnitus, to a situation where tinnitus is extremely bothersome. What they found is that while both noise and stress had an influence, stress was the most important factor for the transition from mild to severe tinnitus. The authors concluded that stress management strategies should be included in hearing conservation programs, especially for individuals with mild tinnitus who report a high stress load.

This finding aligns with the other studies mentioned earlier that found activity in the thalamic reticular nucleus and in the basal ganglia can be highly impacted by stress.

Revised Habituation Model

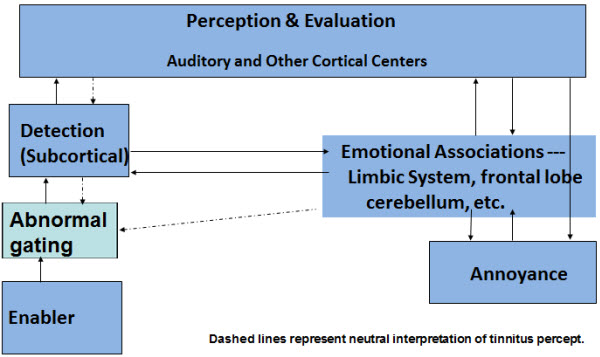

Based on the concepts we have discussed thus far, I’ve taken the liberty to alter the well-known habituation model that Pawell Jastreboff and Jonathan Hazell talked about 20 years ago (Jastreboff & Hazell, 1993). Figure 1 takes their model and accommodates some of the current research.

Figure 1. Revised habituation model (after Jastreboff and Hazell,1993).

In the Jastreboff and Hazell model, there is an enabler, or something that caused the tinnitus. I have added in to this model a box to account for abnormal gating based on the gatekeeper concepts. The enabler would typically be blocked by normal gating. If the gating is abnormal due to damage to that particular region in the brain, then the signal will move through the gate and become detected subcortically. Once it is detected subcortically, it can take one of two paths. It can go up to cortical centers for normal perception and evaluation through the auditory system, and down to the emotional associations areas via the limbic system. I have altered this particular box in the model to indicate that the emotional association is not just in the limbic system. We now know that logic is processed in the frontal lobe, and that the frontal lobe becomes involved. We also know from some of Dr. Carol Bauer’s work that even the cerebellum, an area that is not related to the auditory system per se, also becomes involved. After the subcortical detection of tinnitus, whether it follows the normal route through a conscious perception or takes the subcortical route to the limbic system first, if a negative emotional association is made with tinnitus, then there is going to be subsequent annoyance.

Hearing Aids and Tinnitus

Let’s look at one other study before we get into the management of tinnitus. These are some conclusions from Kochkin, Tyler and Born (2011) that looked at the efficacy of various tinnitus treatment approaches based on patients self-report. They looked at nine different tinnitus approaches. They did not look at specific methods, such as Tinnitus Retraining Therapy (TRT), or Neuromonics Tinnitus Treatment, Widex fractal tones, SoundCure, etc. Rather, they looked at general tinnitus approaches. They found that patients rated hearing aids and music as the best approaches to reduce the distress from tinnitus.

Why would hearing aids help tinnitus patients? As we discussed, if the cortex is not getting the proper stimulation from the peripheral system, then it becomes more active. If hearing aids provide stimulation that was not previously getting through because of the hearing loss, then the cortex is getting stimulation and it may not turn up its gain or sensitivity as much. This might also minimize the amount of cortical plasticity that occurs. Hearing aids also reduce the contrast between the tinnitus and silence. They may at least partially mask the tinnitus. Hearing aids may also reduce fatigue and stress. Remember that stress might in fact be an enabler and certainly is an exacerbater of tinnitus.

Tinnitus Therapies

So let’s look at the three most common approaches to tinnitus therapies. We can look at these tinnitus therapies in terms of three modalities: the auditory modality, the limbic system modality, and the auditory-striatal-limbic connectivity.

The auditory modality is the one we know most about and is where we try to reduce the contrast of the tinnitus. We might cut down the percept of it, and cut down the hyperactivity in the brain by using things like tinnitus maskers, hearing aids, the Neuromonics approach, the Widex Zen fractal tones, or the more recently released SoundCure. Another approach is one from Germany called Coordinated Reset Stimulation that is not yet popular in the U.S. Cochlear implants are another approach designed to affect the auditory modality.

Most approaches also affect the limbic engagement. In doing so, we can reclassify how the person thinks about tinnitus. We can change what they think is important about the tinnitus to mitigate the emotional distress and reduce the tinnitus’ importance to their well-being. Here we find approaches like the counseling aspect of TRT, the counseling program of Neuromonics treatment, and the counseling program of the Widex Zen therapy. Anti-depressants and anti-anxiety medication may also reduce emotional distress. Cognitive-behavioral therapy is becoming probably the most important counseling approach to tinnitus, and this has been borne out by a lot of the research lately. There has also been recent work on mindfulness-based stress reduction, which again is a way to relax the patient to allow them to deal with their tinnitus more effectively. That is going to become very important.

In terms of auditory-striatal-limbic connectivity, in the future we are going to start to see approaches based on the same ideas as the work we have discussed by Cheung and Rauschecker. These approaches will get into things like neural modulation around the basal ganglia. In fact, some recent work looked at vagal nerve stimulation, and then there is ongoing research in the area of rTMS (repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation) that seems to show some promise.

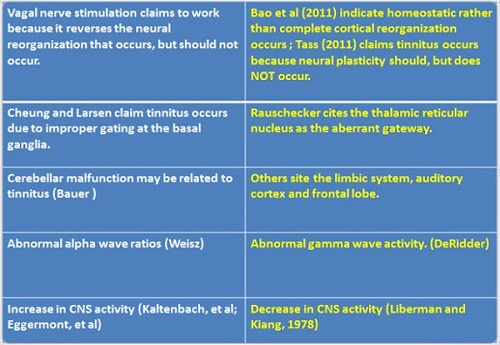

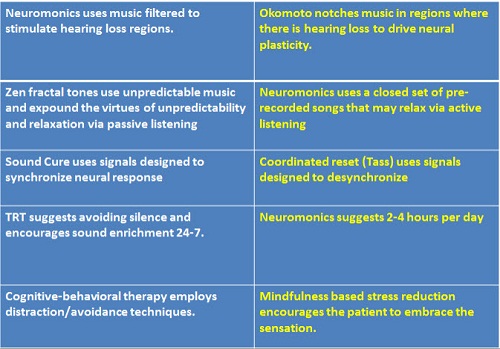

How can diametrically opposed theories and treatments co-exist? We have many different theories about tinnitus as well as a number of different therapies, and many of them are diametrically opposed to one another. Figure 2 lists some of the seemingly opposite theories, and Figure 3 lists some of the seemingly opposite treatment approaches.

Figure 2. Contradictory mechanism theories?

Figure 3. Contradictory treatment approaches?

In terms of approaches, with Neuromonics treatment, you amplify music in the frequency region of the hearing loss and/or the tinnitus, and yet there is another approach out of Okamoto’s lab in Japan that does exactly the opposite (Okamoto, Stracke, Stoll, & Pantev, 2010). It takes music and it purposely filters out the music from the region of the hearing loss and tinnitus. Yet both approaches report success. Can they both be correct? How can they both exist if they are opposite approaches?

We discussed the fact that when you have cortical or neural plasticity, or neural reorganization, than there are certain therapies like vagal nerve stimulation that try to reverse it. Yet you see a couple of other theories that discuss the fact that neural plasticity or neural reorganization does not occur the way it is supposed to. We saw some theories that refer to an improper gating at the basal ganglia. Others show improper gating at the thalamic reticular nucleus. There may be cerebellar dysfunction. There may be auditory cortex, frontal lobe, or limbic system dysfunction. The alpha waves may be off. The gamma waves may be off. These may sound like opposite approaches and yet they all have some basis of scientific foundation. I mentioned that the Neuromonics treatment amplifies in the region where there is a peripheral deficit. Okamoto’s approach cuts the music out in that region. The Widex Zen fractal tones therapy uses very unpredictable music and it is designed to promote relaxation via passive listening. The Neuromonics uses repetitive music that may relax via more active listening. SoundCure, tries to synchronize the neural response. The Coordinated Reset Approach tries to desynchronize the neural response. TRT tells you to avoid silence 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and it tells you to use some kind of sound enrichment, whether it is a noise amplification, music, etc. Neuromonics suggests you could get the same effect with sound enrichment just two to four hours per day. Most people agree with the idea of sound enrichment at least in the early stages of tinnitus, and most agree that it should be used all the time, although there are others who dispute that.

Cognitive behavioral therapy uses distraction and avoidance techniques, while mindfulness-based stress reduction goes in the opposite direction. It basically has the person embrace the sensation by living in the moment. All these theories are different. Many of them are completely diametrically opposed and yet they all seem to work. How could that be?

Maybe they all seem to work because over time, different parts of your brain become activated by having tinnitus. Early on, maybe just the temporal lobe is affected; later on, the frontal lobe, the limbic system, the cerebellum become involved, and so forth. All of these things may make a difference, depending not only on how long you have had tinnitus, but also on your psychological state and exactly where peripherally the tinnitus is occurring.

Integrated Tinnitus Therapy

Integrated Tinnitus Therapy addresses all of the major components of tinnitus distress: auditory perception, the over-attention that people pay to tinnitus, the emotional component of tinnitus, and sleep difficulties. It is important not to omit the sleep difficulties. Just as 80-90% of people with tinnitus will not seek therapy, many patients will be adequately served by counseling and sound therapy. Sound therapy may be hearing aids, noise generators, and/or listening to music. I particularly like the idea of hearing aids with additional acoustic options that I will discuss later. People who have very negative reactions to their tinnitus may need a comprehensive integrated tinnitus therapy that includes cognitive-behavioral concepts and relaxation, along with the counseling and acoustic tools.

Tinnitus and Insomnia

Sleep is the number one complaint from people who have tinnitus. Not everyone with tinnitus has sleep disturbances, but a significant number of patients do and so ignoring the sleep disturbance is not a good idea. A study by Yaremchuk and colleagues (2012) found that the severity of the TRQ was shown to be a good predictor of sleep disturbance and of group association, especially the “emotional” subscore component. They also noted that the more severe the insomnia, the more severe the patient complains about their tinnitus.

Components of Integrated Tinnitus Therapy

The components are the following:

Counseling. Counseling will educate the patient and assist the limbic system to change its interpretation of the tinnitus. We are going to use a couple of counseling approaches to get to that point.

Amplification. Amplification is usually done in a binaural manner because if you amplify one ear and not the other, you are going to run into situations where the person may notice tinnitus in the ear that they previously did not notice tinnitus. This is not to say that we are going to amplify an ear with perfectly normal hearing. We obviously never want to do that, but we would want to stimulate it with some kind of sound perhaps. Why do we use amplification? We want to stimulate the ears and brain in order to discourage an increase in central activity (overcompensation), and reduce maladaptive cortical reorganization.

Acoustic therapy. The acoustic therapy can take the form of music, fractal tones, s-tones, noise, and other stimuli. It is designed to relax the patient because we know about the effect of stress on tinnitus, and also to provide acoustic stimulation. Again, we want to deliver the therapy binaurally. I like the idea of providing the therapy in a discreet, inconspicuous and convenient manner. In other words, if we can get away from earphones that would be nice, but in some situations, earphones are used to present the acoustic therapy.

Relaxation. A relaxing strategy program highlighted by behavioral exercises is the final component.

In terms of disclosure, I am a part-time consultant with Widex, and I have been involved in writing their Widex Zen therapy manual as well as working with them on the development of their fractal tones. It is not the only approach out there that can help tinnitus patients. A lot of approaches can, and as I mentioned at the start of my talk, I am going to try to keep this an unbiased as I can.

Tinnitus Questionnaire

We will always start with a tinnitus questionnaire, which is usually mailed to the patient ahead of time or filled out with the intake paperwork before the appointment. The tinnitus questionnaire should cover these areas: Otologic, medical and audiologic histories; diet; exercise; emotional pattern; sleep and previous treatments. You want to find out how the patient is relating to their tinnitus and the details of their history. We also then need a subjective assessment scale.

There are a lot of subjective assessments available such as:

- Tinnitus Severity Scale (Sweetow & Levy, 1990)

- Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (Newman, Jacobson, & Spitzer, 1996))

- Tinnitus Handicap Questionnaire (Kuk, Tyler, Russell, & Jordan, 1990)

- Tinnitus Effects Questionnaire (Hallam, Jakes, & Hinchcliffe, 1988)

- Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (Wilson, Henry, Bowen, & Haralambous, 1991)

- Tinnitus Cognitions Questionnaire (Wilson & Henry, 1998)

- Tinnitus Functional Index (Meikle et al., 2012)

The first on the list, the Tinnitus Severity Scale, is one that I was actually involved in, and I would not recommend it as I think it is the weakest of this group. I think the strongest of this group in terms of an integrated approach like I am proposing is the Tinnitus Functional Index, which is new. It is a free download from Oregon Health Science University.

You have the slides of the presentation today as a reference and I encourage you to check out the resources that may be of interest to you. We do not have the time to go over every one of these assessments in detail, but I will point out a few things about the Tinnitus Functional Index. I like this assessment as it gets into a lot of different areas. It is a short little index of 25 questions, but it covers some good areas.

The Tinnitus Functional Index uses a 10-point scale, and looks at how tinnitus affects concentration, how it affects sleeping ability, and how it affects hearing. Of course we do not think that tinnitus necessarily affects your hearing, but it may affect the ability to listen and concentrate. It also looks at how tinnitus affects social activities. Some of the questions include: How anxious are you because of tinnitus? How bothered are you? How depressed are you? I like this particular scale. I also like the fact that it has been well-researched in terms of being used for pre- and post-therapy assessment to determine the effectiveness of treatment. It is a sensitive scale for that, and thus can be used for baseline and outcome measures.

Initial Interview

A good initial interview is important to go over the findings on the questionnaire and self-assessment. During this time, you’ll also start to educate the patient about the probable cause of the tinnitus, and the fact that tinnitus is probably a normal consequence of hearing loss, which is important for the patient to hear. We want to provide appropriate reassurance that the tinnitus does not represent a grave illness or a progressive condition, based on the results of a previously conducted medical evaluation. Of course, if the patient has unilateral tinnitus or does not know the cause of the tinnitus, it is critically important that they see a physician before you start on your therapy. Try to involve the patient’s family in treatment, as they can provide emotional support and help motivate the patient to comply with your recommendations.

Counseling

The counseling approaches that we are going to use are in two main categories: instructional counseling and adjustment based counseling.

Instructional counseling. Instructional counseling refers to educating the patient about the aspects of the tinnitus. Instructional counseling will educate the patient on the anatomy and physiology of the auditory system, why the tinnitus is present, what the logical course is going to be, how the limbic system affects the patient, and about habituation. Habituation can be explained like this: we are all habituating to a number of things at this moment. We may be habituating to rings on our fingers, glasses on our face, and the clothing on our body. We naturally habituate to something because we get repeatedly exposed to a stimulus that we interpret as being unimportant. This repeated exposure is one of the reasons why people feel that masking itself does not work very well, because with masking, it can cover up the tinnitus and then you are no longer exposed to the tinnitus. Though there are some people like Rich Tyler who have generated some data that show that masking can in fact lead to habituation. So this may be a little controversial.

The limbic system is important counseling point, and I recommend showing a slide or a poster of the limbic system to your patients. The two most important components of the limbic system for tinnitus are the hippocampus and the amygdala, and I point these out to the patient on the poster. The hippocampus’ role is to identify or tap into your memory banks and identify the source of signal, and the amygdala’s role is to determine whether there is any emotional association that should be made with the tinnitus. For example, if we think about how our sensory systems normally suppress different stimuli, we can think in terms of somatosensorially, when we sit on our rear end, that signal goes up to our somatosensory system. The somatosensory cortex analyzes the signal by counting how fast the nerves are responding, how many nerves are responding, and what their temporal sequence is. It then sends a signal back from the somatosensory cortex to the hippocampus, which identifies the signal based on its electrical firing characteristics. Then, the amygdala determines whether or not the signal is important enough to pay attention to. In the case of our normal somatosensory influence, for example let’s use the example again of sitting, we can quickly habituate to that feeling because the hippocampus identifies it as our rear end. The amygdala says this is not important and it does not impact us in any negative manner, and so we do not have to worry about it. Through the autonomic nervous system, the amygdala sends back messages to the brain that tell it not release any neurotransmitters, or pay attention to this, just forget about it. This is habituation.

Let’s look at an example with sound. When we hear a loud sound like thunder, we also can habituate to it. You may think a loud sound would signal danger. However, in the case of thunder, ur auditory cortex analyzes the signal, the hippocampus identifies it as thunder that is outside and is not dangerous, and then the amygdala indicates that it is not dangerous. The amygdala tells the system there is no reason to react to it. Now consider the opposite reaction, when a soft sound may be considered dangerous. I like to use this analogy with patients: let’s say that someone is lying in bed at home alone and hears the floor squeaking in the next room. In a situation like that, the auditory system picks this very soft signal - the floor squeaking – and the hippocampus identifies it as the floor, but now the amygdala determines this is a potential danger. Maybe it is a burglar, and we need to pay attention to this. As a result, the amygdala through the thalamus sends neurotransmitters and chemicals into the autonomic nervous system like adrenaline, so the person can fight or get up and run away, or do whatever is needed in that situation.

In the case of tinnitus, the same kind of thing can occur. You can get into a situation where your auditory system analyzes the tinnitus, your hippocampus tries to identify it by the electrical firing pattern, but it cannot identify it as a sound, and now your amygdala thinks it is dangerous. Your thought pattern may go something like this: Maybe I have tumor, maybe I am dying, maybe I am going deaf, maybe I am never going to be able to sleep or concentrate again. Now the amygdala instructs the auditory system to pay more attention to the tinnitus, and you set up a vicious cycle that increases the stress about the tinnitus. The instructional counseling should focus on remembering that sequence: the auditory cortex analyzes, the hippocampus identifies, and then the amygdala determines how important it is, and whether or not neurotransmitters need to be released.

Adjustment based counseling. Adjustment based counseling entails talking to the patient about how the tinnitus is impacting him or her along with the cognitive and behavioral implications. With adjustment based counseling we will try to address the emotional sequelae of the tinnitus including fear, anxiety, and depression. We will identify and correct what I am going to call maladaptive thoughts and behaviors. We will also help the patient to understand the relationship between tinnitus, stress, behaviors, thoughts, and quality of life.

Awareness – cognitions – emotional state. Cognitive behavioral intervention identifies unwanted thoughts and behaviors, challenges their validity, and tries to replace them with alternative logical thoughts. When you first become aware of tinnitus, that awareness does not lead to an emotional reaction. In fact, the awareness of tinnitus leads to automatic thoughts; it leads to your cognitions about the tinnitus. These thoughts may include things like: Is this dangerous? Is this scary? Is this going to affect my well-being? These thoughts are what then lead to your emotional state. Your emotional response is not the result of the event (awareness of tinnitus), but rather the result of your thoughts.

To impact the patient’s emotional state, we want to change the thoughts and cognitions. We cannot necessarily change the awareness of tinnitus, although sound therapy may help to some degree. What we want to do is change the cognitions and that subsequently will change the emotional state. We want to remove the beliefs and fears that are creating the emotional reaction, and the best manner of doing this is with cognitive behavioral intervention.

So how do we do this? First, identify the behaviors and thoughts affected by the tinnitus. List the patient’s maladaptive strategies and cognitive distortions. Challenge the patient to identify these thoughts and to come up with alternative thoughts. Some ways to challenge negative thoughts are by asking:

- What is the evidence that my thinking is true?

- What facts am I ignoring or forgetting?

- What are some alternative ways of thinking about this situation?

- What is the worse thing that could happen?

- How likely is it that the worse thing could happen?

- What is probably or most likely to happen?

For example, you might have a situation where the patient says, “I wake up in the morning. I hear my tinnitus. I know it is going be a horrible day, and that is my thought. My behavior is that I am going to stay in bed all day.” Ask the patient to think of alternative thoughts or behaviors. They do not have to believe it, but ask what else could they do when they wake up and notice the tinnitus in the morning. Do you know for a fact or have evidence that it is going to be a horrible day? Maybe they will win the lottery on that day. Do they know for a fact that staying in bed is going to help? They may say, “If I actually get out to the shopping mall, I will not hear the tinnitus as much and I will not think about it as much because I will be distracted and I will find things to do that are more fun.” This can be very helpful. I also approach my patients by having them face up with what is the worst thing that might happen with the tinnitus. If it is not an evidence-based thought, I will challenge them on it. How likely is it that this worse thing is going to happen? What is more likely to actually happen?

- This is a list of cognitive distortions:

- All or nothing thinking

- Jumping to conclusions

- Mental filter

- Magnification

- Labelling

- Over generalization

- Emotional reasoning

- Personalization and blame

- Discounting the positive

- Should statements

I have had patients who come back and say, “I am doing a lot better right now, but I still hear my tinnitus. Therefore, I’m as bad off as I was before.” That is not true. They are doing a lot better since they are not really thinking about their tinnitus as much. This statement is an example of all or none thinking (If I hear my tinnitus at all, I haven’t improved), and also an example of over generalizing. In addition, they are discounting the fact that they are doing better and not thinking about their tinnitus as much as they were before treatment.

I give my patients a list of these distortions and talk to them about it, and I find it helps a lot.

Sound Therapy Considerations

The next component of this integrated approach, after we have done a lot of counseling, is sound therapy. There are a lot of different sounds out there that can be used. Fan-Gang Zeng’s group at UC Irvine has looked at attempts to suppress tinnitus using electrical stimulation as well as auditory stimulation, and the work is very interesting (Reavis et al., 2012). Jim Henry did a study in 2004 that came to the same conclusion (Henry, Rheinsburg, & Zaugg, 2004). That is, to produce suppression or to maintain a triggered response in the higher auditory system, a modulated signal tends to be more effective than a steady-state signal. We know that tinnitus is related to something in which the synchrony is altered in some manner, because you would not get a synchronized response to a non-auditory signal except in the case of tinnitus. Then it makes sense that using some kind of a dynamic signal as opposed to a steady state noise or something like that may alter the synchronized response. Also, since we now know that tinnitus impacts a wide area of the brain, it makes sense to use an acoustic stimulus that activates a widespread area in the brain rather than a limited area of the brain such as only the temporal lobe. That is where music comes into play.

Music. Neuromonics was the first treatment that talked about the use of music. Music has been shown to activate the limbic system and other brain structures (including the frontal lobe and cerebellum) and has been shown to produce physiologic changes associated with relaxation and stress relief.

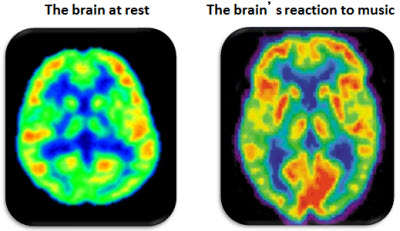

Figure 4 shows two PET scans. The PET scan on the left is a brain at rest, and the PET scan on the right is showing the brain’s reaction to music.

Figure 4. Brain at rest (left) versus when listening to music (right).

You see a much wider region that is activated, not just in the temporal lobe, when you are in fact listening to music.

Where is music processed? Music goes to the cerebellum. That is why you tap your feet. You use your memory for music in the hippocampus. You have emotional reactions to music, and I think very importantly, in the nucleus accumbens, you have a reaction to music that controls the release of dopamine. Dopamine is related to habit formation and also to addiction, and in my opinion, tinnitus patients are in many cases addicted towards listening to their tinnitus. We know that there are certain rules of music when it comes to emotions. Slow music tends to be more calming and relaxing, particularly music that beats at about the rate of the heartbeat (60 – 72 beats per minute), and we know that repetition, to some extent, can be emotionally satisfying.

What is the right music? This is heterogeneous because people have different preferences for music that might be inherited or learned, and they may have cultural preferences. Most importantly, the music should be relaxing so that it activates the parasympathetic division of the nervous system and not the sympathetic division. We also have to be cautious about creating “ear worms”, or those songs that get stuck in our head.

What is the ideal music to use for sound therapy? Hann and colleagues (2008) provided the following strategies for music selection for tinnitus management. It should evoke positive feelings; not include vocals; and not have a pronounced bass beat. It should be pleasant, but not too interesting or compelling (though for short term relief in the beginning of treatment, attention-capturing music can help to distract). The music should induce relaxation. We want it to play at a fairly low level where the music kinds of blends with the tinnitus, and does not cover it up. The level should allow you to hear the music, and mix with the sound of the tinnitus. This is what the concept behind the Neuromonics treatment.

Fractal tones. This then leads to the concept of fractal tones. Fractal tones are different in that they are self-similar tones that have a recursive algorithm so that you can never predict what is coming next. They are melodic. They sound familiar. They follow the appropriate tempo and pitch for relaxation. There are no sudden changes in tonality or tempo. They follow the right chords, but they vary enough to not be predictable. In the Widex Zen fractal tones therapy that I have worked on, there are a number of different areas that you can alter to enable different choices in tempo, the dynamic range, the chord tonality, and the pitch.

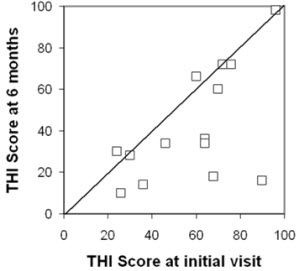

You need to consider the evidence for all of these treatments. In 2010, Jennifer Henderson-Sabes and I published the results of a study in JAAA. We looked at the initial scores on the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) (Newman et al., 1996) and the Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ) (Wilson et al., 1991) for 14 adults with tinnitus. Participants subsequently wore hearing aids containing several programs including amplification only, fractal tones only, and a combination of amplification, noise, and/or fractal tones, and were given the THI and TRQ again after six months of treatment.

We found that the majority of patients showed much relief, and some made enormous improvements (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Tinnitus Handicap Inventory scores pre/post treatment (adapted from Sweetow & Henderson-Sabes, 2010).

You can see from the figure, that one participant started with a THI score of 70 and ended up at 18. There is another participant who started with a THI of 90 and ended up at about 16. The are tremendous improvements. Also, you can see that there were some people that did not improve. The reality is that there is no single tinnitus treatment that universally will show improvement for every person. In fact, 30% of people drop out of tinnitus studies because they do not like the noise, or they do not like fractal tones, or they do not like S-tones. This means 100% cannot succeed. If 30% drop out in the beginning, the best you are going to succeed with is 70%, and then you will succeed with a certain percentage of that 70% with sound therapy alone. Then when you add proper counseling, you might really get close to your 100%. We found that fractal tones promote relaxation and reduce the annoyance of tinnitus, and that noise will also reduce the annoyance of tinnitus. In terms of relaxation, musical tones are more enjoyable to listen to than a simple noise. When you look at tinnitus studies, be sure that you look at the subject population that was included, how many people dropped out, consider the individual statistics as well as the group statistics, and also look at the benefit/cost analysis. Are the participants getting something out of the device? For example, if they have a hearing loss, can it also help their hearing as well as their tinnitus?

Relaxation Exercises

One of the last components of tinnitus treatment that I want to speak about is the importance of relaxation exercises. In an integrated approach, I think you need to have the patient learn about progressive muscle relaxation, where they can learn in a simple manner how they can alternately tense and relax different muscle groups to help them identify where in their body they are manifesting tension. This is included in the Zen manual that I wrote for Widex. Relaxation should also include deep breathing because it is very difficult to be tense when you are going through deep breathing exercises. Deep breathing can be combined with guided imagery to promote relaxation. Guided imagery, for example, is where you have the patient imagine themselves in a comfortable place, floating on a cloud, walking on the beach, walking in a forest, and integrating all of their senses such as olfactory, taste, somatosensory, and auditory to try to imagine this relaxing situation. You could get scripts for guided imagery from the Zen manual, as well as off the Internet.

Finally, as I mentioned earlier, do not ignore the issue of sleep when you are working with patients with tinnitus. This may involve working with a physician to get sleep medication prescribed for the patient, or whether to use sleep suggestions. You can talk through some of these ideas with your patients to find what may work for each individual, whether it may something as simple as changing the number of pillows, which may even help them from a somatosensory perspective.

Conclusions

Tinnitus patients who have hearing loss (i.e. the majority of tinnitus patients) may best be served by amplification that incorporates low compression thresholds. With low compression thresholds, even in quiet settings there will still be some amplification to stimulate the peripheral system, which then stimulates the central system, which then might reduce the over-compensation of the central system. A broad frequency response and flexible options for acoustic stimuli are also important. Not everyone is going to like fractal tones. Not everyone is going to like the repetitive Neuromonics songs. Not everyone is going to like a broadband or narrow band noise. Not everyone is going to like the S-tones from the Sound Cure. You need to have flexible options for tinnitus patients. Make sure that the therapy is tailored for each individual’s functional and financial needs. Having a patient spend too much money on a device that may or may not work for them is just going to increase the stress level and make things worse. The functional needs will be addressed by the whole concept of cognitive therapy. In my opinion, nothing is more important than that. You really need both sound therapy and counseling to make it work.

Thank you for listening today.

Questions and Answers

Does stress cause tinnitus or exacerbate it?

Stress absolutely exacerbates tinnitus. We now believe that it can also cause it, based on some of the things that go on in the limbic system itself and in the basal ganglia where dopamine is released via the nucleus accumbens. So yes we do believe that stress may actually cause tinnitus, but we do not have as much firm data as we do about stress exacerbating tinnitus, which we know it does.

Are there any pharmacological studies that are showing success in brain reorganization?

That is an interesting question. I do not know of any pharmacological studies that show more success in brain reorganization. If you take Zoloft and it relaxes you more, that is going to essentially change your brain rewiring, and so I guess in that sense, any drug will change your brain rewiring. Every time you think about something you start having brain rewiring. There is no study that shows a specific drug that is the most effective. I think you need to target a drug to the symptom. If a patient is depressed, an antidepressant may be indicated. If they are anxious, an antianxiety might be indicated.

Someone has asked about reactive tinnitus. Does sound therapy increase tinnitus?

This is a tricky one. Reactive tinnitus is when people say that any sound makes their tinnitus even louder. This is fortunately pretty rare. Sound therapy can increase the tinnitus especially initially, and so when I start with my patients I would say, “We are going to use a sound because it is important for you not to become afraid of sound.” We do not want them to become phonophobic. I would start with such patients at a very low level and gradually increase the sound to the mixing point.

Is there any way to treat this tinnitus where it would not be passed on to the hearing center and become a sound?

The only way I would say is perhaps through something like a cochlear implant where you are actually altering the tinnitus before it reaches the subcortical level. So let’s say the tinnitus is related to middle ear dysfunction because you have a conductive hearing loss, well then if you treated the hearing loss and treated the middle ear problem, then it would not get passed on to the central system. But right now there is nothing that can be done at the hair cell level before it gets to the hearing center.

Have you found that tinnitus patients might be missing a particular vitamin or mineral in their diet?

I do not know about that. There have been a lot of studies that looked at things like niacin. There have been studies that look at gingko biloba. Michael Seidman has published a number of studies looking at nutritional effects on tinnitus. Surely if a person is zinc deficient or something like that, that might make things worse, but there is no specific nutrient or vitamin supplement that would be universally beneficially for all tinnitus patients. If you know what is missing, then you can deal with that and that may or may not be beneficial.

Can allergy cause tinnitus?

Yes it can. Thousands of things can cause tinnitus. At the House Ear Institute or House Ear Clinic they do a lot of work with tinnitus patients and use allergy treatments a lot. Yes it can cause tinnitus. If you know the underlying cause of tinnitus it can be treated, and we all ought to be doing that as much as possible for these patients.

What are possible causes of loss in the volume of medial prefrontal cortex?

I do not actually know what causes that change. That is just something that has been reported by Rauschecker. I do not know if it again has to do with the whole concept of neural plasticity that if there is a change, let’s say in the thalamic reticular nucleus, if it somehow alters the electrical activity that goes to the medial prefrontal cortex and if it does not get that activity, maybe it then loses its volume. I am really not sure. That is a great question for Joseph Rauschecker.

Can similar therapies be used to treat hyperacusis?

The answer is yes, but I can tell you for sure that with TRT there have been a lot of studies with that. I know when I was using the Neuromonics a lot that I found the Neuromonics to be more effective for hyperacusis than I did even for tinnitus. I will tell you that, I do not think that the S-tones have been looked at for hyperacusis, and I know that the fractal tones in terms of the Zen therapy for hyperacusis have not been looked at, but it would seem to me that it would be a similar kind of approach that you can use.

Are there any in-person counseling trainings available for audiologists?

Yes there are. I give a lot of talks on behalf of Widex and at state meetings as well. The TRT training gets into a lot of instructional counseling, not really training in terms of cognitive behavior counseling, which again I think is just really a great approach to use. It is used more in England than it is here. Laurence McKenna is a great speaker on cognitive behavioral therapy out of England. There is training in that sense. There are other people who do go around and give talks on tinnitus, and a lot of your main tinnitus speakers will also talk about what to say during counseling. Regarding cognitive behavioral therapy, some people get afraid of it because they think that is something that psychologists do, not audiologists. But really much of it is common sense. It is something that we do with our friends, with our spouses, with our kids on a daily basis. Just challenging the patient’s logic and having them replace their thinking with alternative thoughts that can be used can be very helpful.

Have you used any smartphone apps? I have and they are pretty effective.

Yes I have downloaded a couple of things, and yes a smartphone app can be used as effectively as anything else in terms of the sound therapy component of this integrated approach. You can filter a lot of various noises. You could use binaural beats. You can download some forms of fractal music, although I do not think that you can then control like the tempo and pitch the way you can when you get it within a hearing aid. I would certainly encourage people, particularly for sleep, to download an app that is a noise generator, put it next to their bed, get a pillow speaker and utilize that in an effective manner.

Slide 14 said that white noise is ineffective as a tinnitus suppressor, but slide 17 said to use a white noise machine. Why the contradiction?

The answer is that suppressing tinnitus means that you are actually making it go away, and it is very difficult to suppress tinnitus. Suppressing tinnitus is very different than reducing the impact of tinnitus. I would love to be able to suppress tinnitus in every situation, but you usually cannot; so my approach is to provide the patient with tools to help them habituate, to help them cope with their tinnitus, and to reduce the auditory perception of it. There are very few approaches that can actually suppress the tinnitus and what I referred to in that slide 14 was all related to Fan-Gang Zeng’s research using electrical and acoustic modulated signals. So they said a white noise would not suppress it, where their modulated signals would. But I am a believer in white noise for helping a person sleep and things like that. I have tinnitus and I sleep with a fan on every night. It does help me in that sense.

Has Pick’s disease frontal lobe been associated with tinnitus-related dysfunction in any of your studies?

That is a good question. I have not seen it, but it is a great research project. If you do not have your PhD yet, you might go ahead and do that because I am sure that you have a lot of time to do a study like that. No, but that is a really good possibility. I do not know. All of these things with the frontal lobe and the cerebellum, I wonder, is it damage to the frontal lobe that then impacts the tinnitus, or is it the tinnitus that impacts the frontal lobe? I think in the case of the frontal lobe it is the latter; that tinnitus makes changes in the cerebellum and the frontal lobe, and so on. But certainly in the situation of damage to the caudate nucleus or thalamic reticular nucleus, it might in fact be damaged there but then impacts the tinnitus rather than the other way around.

How effective are maskers on musical ear syndrome?

By musical ear syndrome if you are talking about auditory hallucinations, maybe you can give me a little more clarity on that, but if you are talking about musical auditory hallucinations, I do not think that maskers would be effective because a masker, per se, you would have to make it really loud in order to probably cut out the perception. Once put a hearing aid on a guy who had auditory hallucinations in one ear. It was a combination hearing aid and noise generator. He had a pretty bad hearing loss, but it was enough to change his auditory hallucinations. Auditory hallucinations are a different animal than tinnitus per se. Auditory hallucinations are more like a temporal lobe epilepsy, so I would think that one of the first approaches on something like that might be a drug like Neurontin or something along those lines.

What at the three components of tinnitus distress?

Those three components would be the auditory component, the attentional component, and the emotional component.

Thank you for your attendance and participation today.

References

Baigi, A., Oden, A., Almlid-Larsen, V., Barrenas, M.L., Holgers, K.M. (2011) Tinnitus in the general population with a focus on noise and stress - A public health study. Ear & Hearing. 32(6),787-789.

Cheung, S.W., & Larson, P.S. (2010). Tinnitus modulation by deep brain stimulation in the locus of caudate neurons (area LC). Neuroscience, 169(4), 1768-78.

De Ridder, D., Vanneste, S., Kovacs, S., Sunaert, S., Menovsky, T., Van De Heyning, P. (2011). Transcranial magnetic stimulation and extradural electrodes implanted on secondary auditory cortex for tinnitus suppression. Journal of Neurosurgery, 114(4), 903-11.

Hallam, R.S., Jakes, S.C., & Hinchcliffe, R. (1988). Cognitive variables in tinnitus annoyance. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 27, 213-222.

Hann, D., Searchfield, G.D., Sanders, M., & Wise, K. (2008). Strategies for the selection of music in the short-term management of mild tinnitus. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Audiology, 30, 2.

Henry, J.A., Rheinsburg, B., & Zaugg, T. (2004). Comparison of custom sounds for achieving tinnitus relief. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 15, 585-98.

Jastreboff, P.J., & Hazel, J.W.P. (1993). A neurophysiological approach to tinnitus: clinical implications. British Journal of Audiology, 27,7-17.

Kochkin, S., Tyler, R., & Born, J. (2011). MarkeTrak VIII: Prevalence of tinnitus and efficacy of treatments. The Hearing Review, 18 (12), 10-26.

Kuk, F., Tyler, R., Russell, D., & Jordan, H.Y. (1990). The psychometric properties of tinnitus handicap questionnaire. Ear and Hearing, 11, 434-445.

Meikle, M.B., Henry, J.A., Griest, S.E., Stewart, B.J., Abrams, H.B., McArdle, R…Vernon, J.A. (2012). The Tinnitus Functional Index: Development of a new clinical measure for chronic, intrusive tinnitus. Ear & Hearing, 33(2), 153-76.

Newman, C.W., Jacobson, G.P., & Spitzer, J.B. (1996). Development of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Archives of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, 122(2),143-148. doi:10.1001/archotol.1996.01890140029007

Okamoto, H., Stracke, H., Stoll, W., & Pantev, C. (2010). Listening to tailor-made notched music reduces tinnitus loudness and tinnitus-related auditory cortex activity. PNAS, 107(3), 1207-10.

Rauschecker, J.P., Leaver, A.M., & Muhlau, M. (2010). Tuning out the noise: Limbic-auditory interactions in tinnitus. Neuron,66(6), 819-826.

Sweetow, R.W., & Henderson-Sabes, J. (2010). Effects of acoustical stimuli delivered through hearing aids on tinnitus. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 21(7), 461-473.

Sweetow, R.. & Levy, M. (1990). Tinnitus severity scaling for diagnostic and therapeutic usage. Hearing Instruments, 41, 20-21, 46.

Weisz, N., Moratti, S., Meinzer, M., Dohrmann, K., & Elbert, T. (2005). Tinnitus perception and distress Is related to abnormal spontaneous brain activity as measured by magnetoencephalography. PLoS Med, 2(6), e153. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020153

Wilson, P.H., & Henry, J.L. (1998). Tinnitus Cognitions Questionnaire: Development and psychometric properties of a measure of dysfunctional cognitions associated with tinnitus. International Tinnitus Journal, 4(1):23-30.

Wilson, P., Henry, J., Bowen, M., & Haralambous, G. (1991). Tinnitus reaction questionnaire: psychometric properties of a measure of distress associated with tinnitus. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 34, 197-201.

Yaremchuk, K.L., Miguel, G., Drake, C., Roth, T., & Peterson, E. (2012, April). The effect of insomnia on tinnitus. Study presented at Combined Otolaryngological Spring Meetings, San Diego, CA.

Reavis, K.M., Rothholtz, V.S., Tang, Q., Carroll, J.A., Djalilian, H., & Zeng, F-G. (2012). Temporary suppression of tinnitus by modulated sounds. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology, 13(4), 561-71. DOI: 10.1007/s10162-012-0331-6

Cite this content as:

Sweetow, R. W. (2013, February). An integrated approach to tinnitus management. AudiologyOnline, Article #11598. Retrieved from www.audiologyonline.com