Introduction

The history of the audiogram dates back to the early days of audiology during and after World War II in the 1940s. The audiogram has become the standard graphical representation of the results of pure tone threshold audiometry. While its ease of clinical use and functionality for reporting purposes is evident, the numerical values assigned to differing degrees of hearing loss may be in need of re-examination. Some people believe that "the audiogram was born out of necessity as the signature tool specific to the hearing scientist's ability to observe, measure, and record hearing behaviour" (Hedge, 1987, p. 105). Fletcher, Fowler, and Wegel in 1922 were the first to coin the term 'audiogram' and used frequency and intensity aspects to describe the degrees of hearing loss (Feldmann, 1970). One of the earliest classifications of severity of hearing loss was given by Guild in 1932. Since this time there have been numerous attempts to categorize the degree or severity of hearing loss by the numerical decibel values assigned to the audiogram (Carhart, 1945; Clark, 1981; Margolis & Saly, 2007; 2008; Parving, 1995; Stephens, 2001). However, one of the most commonly used degree/severity of hearing loss classification systems was proposed by Clark in 1981. It is believed that such a classification system (e.g. mild, moderate and severe) was originally introduced for the purpose of allocating compensation in the United States after the Second World War.

The standard audiogram is being used extensively around the world, and although there are a number of advantages in the current classification, there remain some problems also. In their recent report, Halpin and Rauch (2009) made a case against fitting hearing aids based on pure tone audiometry threshold results. They suggested that it is better to adopt an approach that will accommodate cochlear damage in the prescriptive hearing aid fittings rather than just reverse-engineering the audiometric test results. Saunders (2010) questions why the audiogram is commonly used as basis for fitting hearing aids in the first place. She highlights that this practice goes back to the early history of the audiogram and the inception of hearing aid fittings. It appears that the connections between the audiogram and the communication difficulties are not necessarily well thought out, and the thresholds determined in the audiogram may not be logical in programming hearing aids to process inputs at what we consider to be normal speech and noise levels.

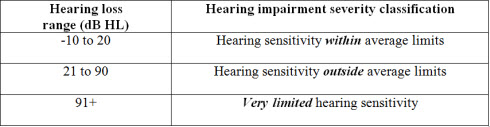

Manchaiah and Freeman (In press) identified some shortcomings of the currently used classification system and proposed a new degree/severity classification for the audiogram (Table 1). They suggest that the "audiological enablement/rehabilitation recommendations should be based on considering wider aspects including pathophysiology, difficulties experienced, abilities, and expectations of the patients and the communication partners, not just the degree/severity of hearing loss itself." This study aimed at looking at audiologists' opinions and experiences about the new classification in audiological practice.

Table 1. Suggested classification for degree/severity of hearing impairment (Manchaiah & Freeman, in press).

Methods

Data Collection

A simple open-ended questionnaire (Appendix A) was designed to collect the opinions and experiences of audiologists towards the new degree/severity classification of the audiogram. A copy of the proposed paper (Manchaiah & Freeman, in press) and the questionnaire were sent to audiologists throughout the world through e-mail. The audiologists were requested to read the attached short paper, use the new classification for a few weeks during their clinical sessions and then provide feedback on how useful the new classification would be by completing the questionnaire. Nineteen out of fifty audiologists completed and returned the questionnaires for a 38% response rate.

Data Analysis

During the first examination of the responses received on the questionnaire, we listed all the advantages, disadvantages and the suggestions made by audiologists. In the next stage, the frequency of given responses and the rakings from least to highest were determined and assigned to the responses. Descriptive statistics for the response scores on 0 to 10 scale are presented.

Results

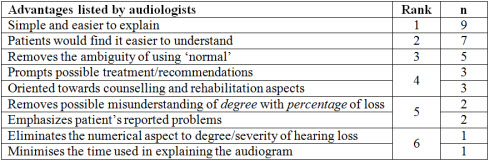

Table 2 lists the advantages of the new classification system recorded by audiologists in the order of the rank of importance and the frequency of response. The majority of the audiologists managed to find at least one advantage of the new classification system. The most common advantage identified was its simplicity of use for the clinician when explaining test results, followed by it being easier to understand for patients.

Table 2. Subjective advantages of the new audiogram classification as reported by audiologists on a random questionnaire.

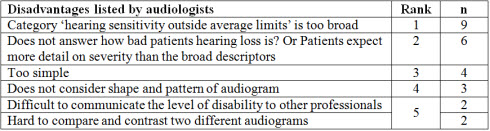

Table 3 lists the disadvantages of the new classification reported by the surveyed audiologists. In general, the main disadvantage listed was that the category "hearing sensitivity outside average limits" is too broad (i.e. it does not differentiate the problems experienced by someone with a 30 dB loss from someone with an 80 dB loss). Also, some audiologists indicated that, "Patients frequently ask 'how bad' their hearing loss is, and the new classification goes no way at all towards answering that query."

Table 3. Subjective disadvantages of the new audiogram classification as reported by audiologists on a random questionnaire.

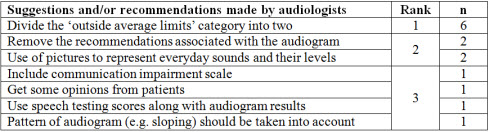

Table 4 lists the suggestions and recommendations made by audiologists to improve the current classification. The most common recommendation was to divide the category 'outside average limits' into two different categories for further description and clarification.

Table 4. Suggestions provided by audiologists on how to improve the proposed audiogram hearing loss classification.

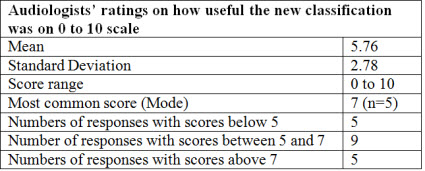

Table 5 presents the audiologists' ratings on how useful the classification was on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 representing not at all useful and 10 representing very useful. The average score was 5.76 (SD=2.78). The most common score was 7, and 14 out of 19 participants gave scores above 5, which may indicate that they favor the new classification to a certain degree.

Table 5. Subjective ratings from participants on the usefulness of the proposed classification of the audiogram (0 = not at all useful; 10 = very useful).

Discussion

Audiologists have identified a number of advantages and shortcomings of the proposed audiogram classification system and have also made several suggestions and recommendations to improve it. The results from the questionnaire indicate mixed opinions and experiences by audiologists around the world about the new degree/severity classification system of the pure-tone audiogram. We consider the subjective scores above 7 to be strong indicators (5 responses) of the acceptance of the new classification, scores between 5 to 7 to be reasonable acceptance (9 responses), and scores below 5 as indicating unfavorable acceptance (5 responses) towards the new system. In general, there is a reasonably good acceptance of the new classification (14 of 19 indicating scores above 5).

One of the main problems identified by audiologists with the current classification was that the category 'hearing sensitivity outside average limits' is too broad, and the top ranked suggestion to rectify this disadvantage was to divide the category into two different descriptors. While we acknowledge this recommendation, we believe that this may go against the primary purpose and rationale of the new proposed classification and may revert back to the same philosophy of all the earlier categorization approaches.

The problems experienced by the patients with conductive hearing loss (e.g. decreased audibility) are different as compared to the problems experienced by patients with sensorineural hearing loss (e.g. decreased audibility, decreased dynamic range, decreased frequency and temporal resolution and combined problems). This is also true when considering the different hearing disorders such as central auditory processing disorders, auditory neuropathy spectrum disorders, et cetera Classifying the degree/severity of hearing loss in audiograms without reference to the results of tympanometry, acoustic reflex testing and otoacoustic emissions denies an enormous string of literature differentiating inner from outer hair cell function. In addition, Erdman & Demorest (1998) argue that patients with similar audiological characteristics may display different degrees of communication handicap. Although degree of hearing loss may be an approach to categorize patients with differing communication barriers into different groups, it has very little clinical value. For this reason, Stephens and Kramer (2009) suggest that audiological enablement and rehabilitation should be based on the perceived or experienced difficulties of the patients rather than the severity or level of hearing impairment.

Furthermore, there is also some dilemma in the way we define hearing and hearing loss, and some expert audiologists believe that there may not be any need for audiologists to explain the audiograms to patients. Cindy Pichler, Au.D., an audiologist at Resurrection Medical Center in Chicago, IL and one of the winners of the 'Defining the Audiogram' competition organized by the Ida Institute, questioned why we should have to explain the audiogram at all (Ida Institute, 2009). Dr. Pichler suggests that it is important to consider what the patient's problem is, what it means, and what we might do about it. Also, in counseling patients regarding their results, there is a need for the message to be presented in a way that facilitates patients' understanding of their diagnoses and their motivation to follow through with recommedations.

We believe that no single classification system will serve all the purposes required in diagnosing and explaining the prognosis of a hearing loss. However, the new classification could be helpful in counselling if it is used in conjunction with discussion of problems experienced by listeners with different types of hearing disorders and the associated problems experienced by those patients. A recent discussion paper by Neumann and Stephens (2011) could serve as a useful reference in classifying the types of hearing disorders. It may take a long time for the new classification to be accepted by audiologists and patients around the world. Even though the new classification may seem too simple and broad, we believe this would allow clinicians more room to adopt holistic approach to audiological management. Some might argue that there is a clear need for change in the approach to categorize the degree/severity of hearing loss on the audiogram. More work is needed to better understand the audiologists' and patients' views regarding this subject. It appears that there is certainly room for improvement on the currently proposed classification.

Limitations of the study

The demographics (e.g. age, sex, experience levels, working set up, and education levels) of the audiologists who responded to the survey were not considered as factors in this study. The responses included opinions and experiences reported by small a number of audiologists and may not represent the wide range of professionals. In addition, there was no control in place to determine if in fact the audiologists surveyed did indeed use the new classification system with their patients prior to providing their feedback.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all the audiologists who provided their feedback on the questionnaire, which made it possible to move forward with publication and additional research efforts in this subject area.

References

Carhart, R. (1945). An improved method for classifying audiograms. Laryngoscope, 55, 640-662.

Clark, J.G. (1981). Uses and abuses of hearing loss classification. ASHA, 23(7), 493-500.

Erdman, S., & Demorest, M. (1998). Adjustment to hearing impairment II: Audiological and demographic correlates. Journal of Speech Language & Hearing Research ,41, 123-136.

Feldmann, H. (1970). A history of audiology: A comprehensive report and bibliography from the earliest beginnings to the present. Translations of the Beltone Institute for Hearing Research, 22, 1-111.

Guild, S.R. (1932). A method for classifying audiograms. Laryngoscope ,42, 821-836.

Halpin, C. & Rauch, S.D. (2009). Hearing aids and cochlear damage: The case against fitting the pure tone audiogram. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, 140, 629-632.

Hedge, M.N. (Ed.). (1987). Observation and measurement. In Clinical Research in Communicative Disorder (pp. 105-106). Boston: College-Hill Press.

Ida Institute. (2009). Winners of defining audiogram challenge. Retrieved July 13, 2011, from idainstitute.com/news/ida_names_winners_of_its_defining_audiogram_challenge/

Manchaiah, V.K.C. & Freeman, B. (In press). Audiogram: Is there a need for change in the approach to categorise degree/severity of hearing loss? International Journal of Audiology.

Margolis, R.H. & Saly, G.L. (2007). Toward a standard description of hearing loss. International Journal of Audiology, 46, 746-758.

Margolis, R.H. & Saly G.L. (2008). Distribution of hearing loss characteristics in a clinical population. Ear and Hearing, 29, 524-532.

Neumann, K. & Stephens, D. (2011). Definition of types of hearing impairment: A discussion paper. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica, 63(1), 43-48.

Parving, A. (1995). Editorial guidelines for description of inherited hearing loss. Journal of Audiological Medicine. 4, ii - v.

Saunders, E. (2010, Decemer 9). Why is an audiogram commonly used as the basis for fitting a hearing aid? Message posted to www.australiahears.com.au

Stephens, D. (2001). Audiological terms. In A. Martini, M. Mazzoli, D. Stephens, and A. Read (Eds.). Definitions, Protocols & Guidelines in Genetic Hearing Impairment. London & Philadelphia: Whurr Publishers.

Stephens, D. & Kramer, S.E. (2009). Living with Hearing Difficulties: The Process of Enablement. Chichester: Wiley.

New Degree/Severity Classification for the Audiogram: What do Audiologists Have to Say?

August 29, 2011

Related Courses

1

https://www.audiologyonline.com/audiology-ceus/course/20q-consumer-reviews-offer-hearing-36108

20Q: Consumer Reviews Offer Hearing Care Insights

This engaging Q & A course discusses research about online consumer reviews in hearing healthcare. The discussion includes what audiologists and hearing care professionals can learn from reviews in order to deliver the best possible patient experience and positive outcomes with hearing care.

textual, visual

129

USD

Subscription

Unlimited COURSE Access for $129/year

OnlineOnly

AudiologyOnline

www.audiologyonline.com

20Q: Consumer Reviews Offer Hearing Care Insights

This engaging Q & A course discusses research about online consumer reviews in hearing healthcare. The discussion includes what audiologists and hearing care professionals can learn from reviews in order to deliver the best possible patient experience and positive outcomes with hearing care.

36108

Online

PT120M

20Q: Consumer Reviews Offer Hearing Care Insights

Presented by Vinaya Manchaiah, AuD, MBA, PhD

Course: #36108Level: Introductory2 Hours

AAA/0.2 Introductory; ACAud inc HAASA/2.0; AHIP/2.0; BAA/2.0; CAA/2.0; IACET/0.2; IHS/2.0; Kansas, LTS-S0035/2.0; NZAS/2.0; SAC/2.0

This engaging Q & A course discusses research about online consumer reviews in hearing healthcare. The discussion includes what audiologists and hearing care professionals can learn from reviews in order to deliver the best possible patient experience and positive outcomes with hearing care.

2

https://www.audiologyonline.com/audiology-ceus/course/20q-over-counter-hearing-aids-41485

20Q: Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids and Service Delivery Models—What We Know, and What Remains Unclear

This course explores the emerging landscape of Over-the-Counter (OTC) hearing aids and Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) hearing care models, highlighting their key differences from traditional devices and service delivery. Current research on the uptake, quality, and consumer satisfaction with OTC devices and how they have impacted audiologic practice and traditional hearing aid dispensing are discussed.

textual, visual

129

USD

Subscription

Unlimited COURSE Access for $129/year

OnlineOnly

AudiologyOnline

www.audiologyonline.com

20Q: Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids and Service Delivery Models—What We Know, and What Remains Unclear

This course explores the emerging landscape of Over-the-Counter (OTC) hearing aids and Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) hearing care models, highlighting their key differences from traditional devices and service delivery. Current research on the uptake, quality, and consumer satisfaction with OTC devices and how they have impacted audiologic practice and traditional hearing aid dispensing are discussed.

41485

Online

PT90M

20Q: Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids and Service Delivery Models—What We Know, and What Remains Unclear

Presented by Vinaya Manchaiah, AuD, MBA, PhD

Course: #41485Level: Intermediate1.5 Hours

AAA/0.15 Intermediate; ACAud inc HAASA/1.5; AHIP/1.5; ASHA/0.15 Intermediate, Professional; BAA/1.5; CAA/1.5; Calif. SLPAB/1.5; IACET/0.2; IHS/1.5; Kansas, LTS-S0035/1.5; NZAS/2.0; SAC/1.5; TX TDLR, #142/1.5 Non-manufacturer

This course explores the emerging landscape of Over-the-Counter (OTC) hearing aids and Direct-to-Consumer (DTC) hearing care models, highlighting their key differences from traditional devices and service delivery. Current research on the uptake, quality, and consumer satisfaction with OTC devices and how they have impacted audiologic practice and traditional hearing aid dispensing are discussed.

3

https://www.audiologyonline.com/audiology-ceus/course/innovative-audiologic-care-delivery-38661

Innovative Audiologic Care Delivery

This four-course series highlights the next generation of audiology innovators and their pioneering approaches to meeting unmet audiologic needs in their communities and beyond. This peer-to-peer educational series highlights researchers, clinicians, and business owners and their pioneering ideas, care delivery models, and technologies which provide desperately needed niche services and audiologic care.

auditory, textual, visual

129

USD

Subscription

Unlimited COURSE Access for $129/year

OnlineOnly

AudiologyOnline

www.audiologyonline.com

Innovative Audiologic Care Delivery

This four-course series highlights the next generation of audiology innovators and their pioneering approaches to meeting unmet audiologic needs in their communities and beyond. This peer-to-peer educational series highlights researchers, clinicians, and business owners and their pioneering ideas, care delivery models, and technologies which provide desperately needed niche services and audiologic care.

38661

Online

PT240M

Innovative Audiologic Care Delivery

Presented by Rachel Magann Faivre, AuD, Lori Zitelli, AuD, Heather Malyuk, AuD, Ben Thompson, AuD

Course: #38661Level: Intermediate4 Hours

AAA/0.4 Intermediate; ACAud inc HAASA/4.0; AHIP/4.0; ASHA/0.4 Intermediate, Related; BAA/4.0; CAA/4.0; IACET/0.4; IHS/4.0; NZAS/3.0; SAC/4.0; Tier 1 (ABA Certificants)/0.4

This four-course series highlights the next generation of audiology innovators and their pioneering approaches to meeting unmet audiologic needs in their communities and beyond. This peer-to-peer educational series highlights researchers, clinicians, and business owners and their pioneering ideas, care delivery models, and technologies which provide desperately needed niche services and audiologic care.

4

https://www.audiologyonline.com/audiology-ceus/course/promoting-interventional-audiology-in-multidisciplinary-38426

Promoting Interventional Audiology in Multidisciplinary Practice

This course describes the negative effects that untreated hearing loss can have on healthcare outcomes and the positive impact that interventional audiology can have on a patient’s care. Several examples and suggestions for providing interventional audiology services are discussed. This course is part of a four-course series, Destroying the Box: Innovative Audiologic Care Delivery which highlights the next generation of audiology innovators and their pioneering approaches to meeting unmet audiologic needs in their communities and beyond.

auditory, textual, visual

129

USD

Subscription

Unlimited COURSE Access for $129/year

OnlineOnly

AudiologyOnline

www.audiologyonline.com

Promoting Interventional Audiology in Multidisciplinary Practice

This course describes the negative effects that untreated hearing loss can have on healthcare outcomes and the positive impact that interventional audiology can have on a patient’s care. Several examples and suggestions for providing interventional audiology services are discussed. This course is part of a four-course series, Destroying the Box: Innovative Audiologic Care Delivery which highlights the next generation of audiology innovators and their pioneering approaches to meeting unmet audiologic needs in their communities and beyond.

38426

Online

PT60M

Promoting Interventional Audiology in Multidisciplinary Practice

Presented by Lori Zitelli, AuD

Course: #38426Level: Introductory1 Hour

AAA/0.1 Introductory; ACAud inc HAASA/1.0; AHIP/1.0; ASHA/0.1 Introductory, Related; BAA/1.0; CAA/1.0; Calif. SLPAB/1.0; IACET/0.1; IHS/1.0; Kansas, LTS-S0035/1.0; NZAS/1.0; SAC/1.0

This course describes the negative effects that untreated hearing loss can have on healthcare outcomes and the positive impact that interventional audiology can have on a patient’s care. Several examples and suggestions for providing interventional audiology services are discussed. This course is part of a four-course series, Destroying the Box: Innovative Audiologic Care Delivery which highlights the next generation of audiology innovators and their pioneering approaches to meeting unmet audiologic needs in their communities and beyond.

5

https://www.audiologyonline.com/audiology-ceus/course/teleaudiology-advancing-access-and-equity-38962

Teleaudiology: Advancing Access and Equity in Hearing Care - Hearing Care in the 21st Century, in partnership with Salus University

This two-part series explores the current state of teleaudiology today, from practice to legislation. Part 1 provides an overview of teleaudiology clinical provision including implementation and challenges using real-world examples.

auditory, textual, visual

129

USD

Subscription

Unlimited COURSE Access for $129/year

OnlineOnly

AudiologyOnline

www.audiologyonline.com

Teleaudiology: Advancing Access and Equity in Hearing Care - Hearing Care in the 21st Century, in partnership with Salus University

This two-part series explores the current state of teleaudiology today, from practice to legislation. Part 1 provides an overview of teleaudiology clinical provision including implementation and challenges using real-world examples.

38962

Online

PT90M

Teleaudiology: Advancing Access and Equity in Hearing Care - Hearing Care in the 21st Century, in partnership with Salus University

Presented by Aaron Roman, AuD, Samantha Kleindienst Robler, AuD, PhD

Course: #38962Level: Intermediate1.5 Hours

AAA/0.15 Intermediate; ACAud inc HAASA/1.5; AHIP/1.5; ASHA/0.15 Intermediate, Professional; BAA/1.5; CAA/1.5; Calif. SLPAB/1.5; IACET/0.2; IHS/1.5; Kansas, LTS-S0035/1.5; NZAS/2.0; SAC/1.5

This two-part series explores the current state of teleaudiology today, from practice to legislation. Part 1 provides an overview of teleaudiology clinical provision including implementation and challenges using real-world examples.