Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Provide an overview of laws that support educational access for children with hearing loss and the responsibility of educational and community audiologists in implementing these laws.

- Discuss the benefits of creating a partnership between an educational/school audiologist and community audiologist on behalf of the child.

- Describe recommendations that support educational and communication goals for school-aged children.

Introduction

Thank you for joining us today as we discuss the value of school and community audiology partnerships. As an audiologist, I see children in the clinic and also provide educational audiology consulting. Recently, a family with a child who has hearing loss came to me for an auditory processing evaluation. They were told that the child’s hearing loss was too slight to be educationally handicapping. As such, they were informed that their school district was not responsible under IDEA. They were a small school district and did not have a lot of money. I share this story with you because part of our responsibility as audiologists is to be aware of the laws so we can support children and families in obtaining services that are right for them, as well as to help listen to and educate school districts.

Erber’s Hierarchy

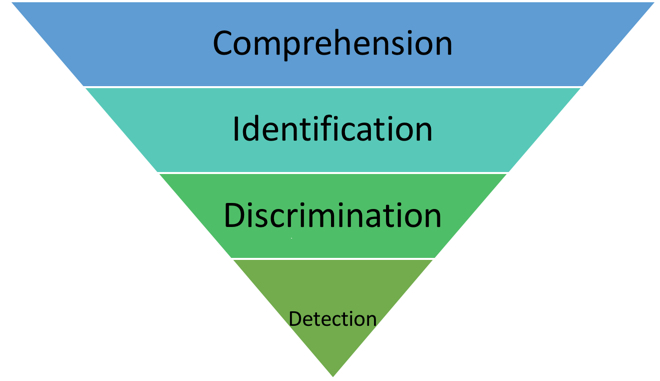

Whenever I give a presentation, I always like to start with Erber's Hierarchy (1992). As audiologists, we often get lulled into the notion that the audiogram tells the entire story, beginning at the point of detection. However, while the audiogram is essential, we must look at the whole hierarchy to fully understand how hearing loss might impact a child at school. Erber’s Hierarchy challenges us to look at a broader perspective to consider not only the audiogram, but also discrimination, identification, and comprehension (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Erber’s Hierarchy.

When working with school-aged children, the Individuals with Disabilities and Education Act (IDEA) indicates that we have to be able to show that hearing loss has an educational impact. When evaluating whether there is an educational impact, what kind of things are we looking at? Does all hearing loss constitute an educational impact?

Because I do a lot of auditory processing testing, I've seen children with auditory processing disorders who have more hearing impairment in the classroom than children with moderate hearing loss who have been aided since birth. Many school districts don't understand the field of audiology or our purpose in the school. When I get a call from a school district to which we provide consultation services, I find it irritating that I'll ask them questions and they are entirely unfamiliar with the concept of an audiogram. When working with a school, it is critical that we can talk to the decision-makers.

Flavors of Audiology

When discussing the different types of audiology, I like to refer to them as “flavors” of audiology. These flavors include clinical audiology and educational or school-based audiology.

Clinical Audiology

As clinical audiologists, we might provide diagnostic services (e.g., hearing evaluation) and rehabilitative services (e.g., hearing aid selection, fitting, and follow-up, auditory training). Those services are generally provided in a center-based facility, such as a community speech and hearing center or a hospital.

Educational/School-Based Audiology

The role of the educational or school-based audiologist is to address the child's need in the classroom using technology (e.g., an FM/DM system), to provide educational assessment (e.g., the Functional Listening Evaluation), to provide in-service training to school personnel, and to advise the school district on equipment, room acoustics, etc.

There can be considerable overlap and cooperation between clinical and educational audiology. However, one of the problems in the United States is that there is no consistency in how educational audiology services are provided to children. Some states have educational audiologists that cover every single school district. In contrast, some states do not enjoy the benefit of a dedicated audiologist. This lack of audiology support can pose significant problems.

As a side note, if you are a center-based audiologist and you're curious about doing school consulting, I would strongly recommend that you look into it. We take our audiology students out to the schools with us so they can see what kinds of questions teachers have, what assumptions are made about children in the classroom, and what is said in IEP meetings. Being immersed in the school setting provides the students with an idea for what they can do to influence audiology in the school setting. I think it is an excellent opportunity for anyone who wants to do educational audiology consulting.

Some districts contract with audiology programs in clinics and hospitals, etc. The audiologists in these programs provide services as requested by the school district, such as independent evaluations and equipment maintenance. In some cases, the audiologist may be providing both clinical and educational services. Unfortunately, some school districts have no audiology support and try to provide these services on their own.

Focus: The Child

Ultimately, when working as a team in a school setting, our collective focus needs to be on the child. Those of us that work in schools get to see the child in their natural habitat and witness how the information obtained from an authentic assessment can be helpful. Audiologists in clinical settings often hear from the parent or the child based on a relationship of trust, and they will provide specific information that augments observations in the classroom. Additionally, it is imperative that we all are performing validation and verification on hearing aid fittings with the child’s technology.

In the school setting, just because a student seems like they're hearing doesn't mean they are. When talking about hearing loss, we often use the terms “mild” and “moderate,” but it may be that those terms are no longer useful. A child with even a mild hearing loss can experience a significant educational impact. We're finally starting to consider listening as a fatiguing and stressful event. For many children with hearing loss, they are fatigued after listening all day, which can impact their function in the classroom. Recently, a little girl (with mild hearing loss) and her father came into my office. This father confided that they jokingly call their daughter “the nap queen,” but he realized that her fatigue might be attributed to hearing loss. We must assess the individual student’s needs, and not base it solely on their degree of hearing loss. We must acknowledge that not all children require the same solutions (e.g., not every child needs an FM system).

In 1985, Liden and Harford wrote an article titled “The Pediatric Audiologist: From Magician to Clinician” (Liden & Harford, 1985). However, since 1985, hearing technology has changed dramatically, they might need to revise the title of the article to be “From Scientist to Magician to Clinician.” Now, we have to look at the psychoacoustics as the basis for the audiology profession. The development of psychoacoustics is the foundation for pediatric audiology. Maybe we need to be more influential in looking at classroom acoustics, including preschool settings. There are also other sciences that have an impact on the field of audiology, such as genetics, microbiology, neurology, and embryology. It would be to our benefit to become familiar with each of these sciences and how they might interact with the field of audiology.

Then vs. Now

During the time that the article was written in 1985, our main concerns were focused on identifying hearing loss in children early (at two to three years of age). Children with hearing loss who went to school were grouped together. The primary hearing loss that was identified in 1985 was severe-to-profound. At that time, if children with lesser degrees of hearing loss were detected at their kindergarten screening or later. In those days, hearing aids were all analog, and body-worn FM systems had a crystal on them. If you were unfortunate enough to drop the FM, it could be months until you got it up and running again.

Today, we identify children at birth using universal newborn hearing screenings. Also, we see children with a broader range of communication issues, as well as children on the autism spectrum. We are re-evaluating what defines hearing. Currently, at Cincinnati Children's Hospital, we're spending a lot of time looking at hidden hearing loss. There are children who have hearing issues, and just because we can't measure their loss does not mean they do not struggle. When I was a young audiologist, we would fit some children with hearing aids, and they didn't do well. We could make the argument that back then, they had analog hearing aids that did not perform well. However, 15-20 years later, we discovered that these children had a condition called auditory neuropathy.

It is important to acknowledge that in this day and age, we're facing new challenges and conditions that we had previously never experienced. For example, many children are referred to our clinic for hyperacusis and misophonia. What is the impact of these conditions in the educational setting? Furthermore, what are the pros and cons of mainstreaming children with hearing loss? These days, most children with hearing loss are mainstreamed unless they go to a school for the deaf or participate in a specialized program. If they are mainstreamed, these children may feel isolated and frustrated if there aren’t any other deaf children in their school, or even in their community. We also have to navigate the many forms of technology that can be used in conjunction with hearing aids, such as Bluetooth, streaming, connect clips, and DM technology.

Pediatric audiology has become a growth industry. For instance, there's an epidemic of concussion and TBI among children in school populations. Also, there are many children on the autism spectrum who require audiology services. There are also students exposed to recreational noise, such as those who participate in choir and band. We need to be cognizant of this noise exposure, both in the community and educationally.

Parents

Often, parents don't fully understand the type of hearing loss or the condition that their child has. I'm always shocked when I meet parents of teenagers who say, "They have that sensory thing, I don't even know what that is." They are struggling to understand the etiology of their teen’s hearing loss. I think this is where the partnership between educational and community audiology can be strong. As audiologists, we can and should provide informational counseling; however, we often miss the mark. How can we improve and provide families with better information?

Basics at the Beginning

When sharing information between the audiologist and school, we need to determine who is the most appropriate contact at school. Most often, it is someone in special education at the school district, but commonly, we find that families are not communicating with the appropriate person. Instead, they'll go to the classroom teacher or the school nurse. If you're a community-based audiologist, can you help them find the correct person? Can you call the educational audiologist and find out who that person is? We need to share information between the community audiologist and the school. We also need to have a copy of the current audiogram. The school is only required to provide a new assessment every three years. We also want to have information about current technology, such as the hearing aid make, model, and serial number, or the cochlear implant processor information. I also like to know the color of the hearing aid that the child is using. If I'm going to order battery doors for an FM or DM, for example, I want to know the correct color, to match the battery door. If we're going to encourage children to want to use FM in school, that's a small thing we can do. The parents also need to sign a release of information so we can talk to each other.

Special Education: Laws and Rights

Ruth Colker is a special education lawyer who has written special education textbooks for law. She's also a parent of a child with a hearing impairment, and she is passionate about what audiologists do. She wrote a book titled “Special Education Law in a Nutshell” (Colker, 2018). Another resource I would recommend is to find out if your state has its own special education guide. The Ohio Department of Education has a guide that is excellent. It is titled “A Guide to Parents' Rights in Special Education: Special Education Procedural Safeguards Notice" and is published in 12 languages, including English.

Determining Disability

To identify and refer a child to early intervention, we begin with each state’s Child Find program and early identification services. Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act (IDEA) requires each state to implement early identification policies to locate and refer children who may have a disability to that state’s early intervention program. Part C of IDEA is the Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP) for children ages three to five. In Part B of IDEA, there are 13 different categories under which a child can be classified to qualify for special education. The ones that we commonly see in audiology are hearing impairment/deafness, deaf-blind, multiple disabilities, speech/language impairment, or other health impaired. We may also see children with metabolic issues or a fluctuating hearing loss. I'm working with a young woman right now who appears to have an autoimmune hearing loss. The school district has classified her under hearing impairment, but they also wanted to classify her as other health impaired, because they believed that she could get more services that way.

The law is clear that being in one of these categories is not enough to qualify as having a disability. Just because you have a hearing loss, you do not automatically qualify as having a disability under IDEA Part B. You must qualify as having a disability. The child must “need” special education or related services. How do we define “need”? There are many unique situations. For example, one school district I worked with would qualify any child with auditory processing disorder under hearing impairment that I requested. Another school district would rarely qualify children with APD.

Determining Adverse Educational Impact

As audiologists, we need to answer the question of whether the hearing loss adversely impacts the child’s ability to participate in the academic program. There are several ways that we can address this question:

- Verification and validation

- Speech in noise testing

- Authentic assessment

- Breadth of recommendations

- Assertion of educational handicapping

Verification and validation. We have already touched on verification and validation earlier in the course. If you can't differentiate /s/ from /sh/, that can be very difficult for a child. In fact, /s/ is one of the most critical phonemes. If a child can't differentiate the /s/ sound with their hearing aids in the classroom, it will be difficult for them to do well in less than optimal environments.

Speech in noise testing. We need to do a better job of speech in noise testing. There are some excellent protocols, such as the AAA protocol on how to fit FM and DM technology.

Authentic assessments. Shortly, we will discuss tools to perform authentic assessments.

Breadth of recommendations. Avoid outdated methods like using tennis balls on chair and table legs. Unless you can measure it, there's not an acoustic benefit to that. In the 1990s, Leavitt and Flexer studied preferential seating and found that unless a child was sitting about 12 inches from the teacher, preferential seating didn't have any real acoustic impact. Now, we can argue that preferential seating is a great thing for a child with hearing loss and that the preferential seat might not be the right in front of the teacher; it might be somewhere else. That seating position may give the teacher visual information about the child, and it may give the child visual access to the teacher. However, we have to stop writing in reports that preferential seating is a solution because it has been shown to have a minimal acoustic benefit (Leavitt & Flexer, 1991). There are methods and techniques that we can recommend to school decision makers which will benefit children with hearing loss. For example, providing the child with class notes ahead of time may be helpful. If there's going to be a movie or YouTube video shown in the classroom, it should be captioned.

Often, when it comes to the decision makers in the school (e.g., the special education director or the psychologist), it is not within their scope of practice to understand what we do as audiologists. If we don't step up and help them to understand, they may go down the wrong path. We need to explain to them that this is our scope of our practice. What is educationally handicapping may not be correlated to the degree of hearing loss. We need to focus on the reality of hearing loss. It can be fatiguing. It can produce anxiety for children when they're not hearing easily. It can be socially and emotionally isolating. We need to raise awareness of the fact that children with hearing loss are at least three times more likely to be bullied than students who don't have hearing loss.

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 indicates that “no individual shall be excluded from participation in a program or activity based on their disability if the activity receives Federal financial assistance” (i.e., schools). In other words, this states that legally, the child does not need special education or related services, even though they have a disability. They're not on an IEP, but they are going to be provided certain kinds of assistance, such as access to an FM or note taking. Even though they don't fit into that IEP, they still have a legal document that supports their rights. As audiologists, we have to be influential in directing families to the decision makers. We have to provide concrete information about the impact of hearing loss and the child's specific technology. We have to help the family understand those issues. School districts can't get away with telling a family that they don’t have enough funding to do certain things.

As an audiologist, if you've not worked with a parent advocate, I would highly recommend this in situations that get difficult or contentious. A parent advocate can be the mediator between the family and the school district. It is a middle ground and a great person to work with from that perspective.

Cochlear Implants and Hearing Aids: Access to Education

Well-fit cochlear implants and hearing aids are great, but they are only part of an educational plan. The Listening Inventory for Education (LIFE) is a helpful questionnaire when examining if something is working for the child. It's a pre-post revised questionnaire. It is easy to ask a teacher if the FM/DM system worked. When you get into the specifics that are in the LIFE, it gives them an opportunity to look at it very differently. To be optimal, hearing aids and cochlear implants must be worn all the time and not just at school. We all have to be on the page that we do not just fit hearing technology on children. We are trying to change their auditory pathways to build a better auditory system. One of the other things that I think we all have to be on the same page about is that to be optimal, hearing aids and CIs must be worn all the time. Not just at school. I sat in an IEP meeting a couple of years ago, and I left very angrily because there was an audiologist in our community who sat there and said, "Well, the child doesn't want to wear hearing aids, so she should only wear them at school." You know, I think we all have to be on the page that we're not just putting hearing aids and technology on children. We're trying to change their auditory pathways to build a better auditory system. So, as much as we can reinforce that for each other, I think it is important.

Secondly, the hearing devices need to be maintained and working correctly. What resources do we need at the school to manage these devices? We also need to provide Real Ear verification when looking at audibility in the classroom and determining the need for setting of specific features (i.e., frequency lowering, directional microphones, HAs with assistive technology). As a team, we need to be on the same page to ensure the student has the best chance to learn with their hearing impairment. Even the best fit technology cannot overcome hearing loss.

So, even the best-fit implants or FM can't overcome hearing loss. Children with cochlear implants have been defined as hearing impaired or deaf children, and that might not sit well with some of you, because implants have come a long way. When a school district is interpreting this, remember, they see it as a black or white. So, if you say, well they have normal hearing, it is not going to get us anywhere, it is not going to get us what we need. The fact that the expectations of learning for most of our children are in an auditory, oral environment impacts how we need to look at the acoustics of the classroom and what we do.

FM/DM Considerations

For hearing loss to be considered by the schools, it has to be educationally handicapping. Not all children need an FM or DM. This may be only one consideration and should not be the only recommendation. We need to look at what the right solution is. Some school districts have a stock of FM/DM solutions that they'll let children borrow to determine the best solution. I mentioned authentic assessments which examines what occurs in the classroom and can be done pre or post FM trial. Here are a few recommendations:

- The Screening Instrument for Targeting Educational Risk (SIFTER)

- The Functional Listening Evaluation

- Listening Inventory for Targeting Educational Risk-Revised (LIFE-R)

IEP.

An IEP is a legally binding document. What if the child refuses to wear FM? Involve the child in their own IEP meetings early on so that they develop their self-advocacy skills. This will require a partnership of everyone involved using a connection between clinical and educational audiologists is helpful. One of the questions that come up sometimes is how do we use home equipment at school? The equipment is the district's responsibility to provide if it is needed. Using personal equipment has many issues. If the district agrees to it, what are the liability issues? Be sure to get this in writing.

Building a Team for the Students

We have to have input from everybody. We all know that parents are experts on their children, and they have to be recognized and appreciated. The clinical audiologist may have worked with the child for years and can provide a unique perspective. The educational audiologist understands the classroom and technology. School placement needs all of this input. Where things go poorly is if we're demanding, accusing, blaming and listening to wrong information. Here is an example, I worked with a school district where one of the manufacturers told the school that the reason the child was having issues with their FM was because of wifi. Everybody reading this course needs to know that's not right, wifi doesn't interfere with FM. The clinical audiologist ran with that idea, and it took a long time to get over that because the parents were very angry that the school couldn't figure it out.

The bottom line is what happened was it was a new hearing aid and the audioshoe bounced up and down when the student was walking. I ended up having this in three different children in two different districts, and the audioshoe was just a little bit too short. Let's assume the best. Let's keep the student as the focus and have reasonable expectations. Parents shouldn't be at school monitoring this stuff. If a problem arises, it is reasonable for them to hear about it. If a clinical audiologist is working with a family and they're talking about dropping off batteries, an educational audiologist or the school district needs to be addressed. If there's a new ear mold, tubing, reprogramming that needs to happen to facilitate the use of an FM or a DM, it needs to occur in a reasonable timeframe. Equipment will need to be repaired, and so a child might need to have their FM/DM sent back in. If that happens, what's the backup plan?

Keys for Success

Involve the child at a young age. How do we empower these students? Children who are most successful are self-confident about their hearing loss. Consider starting a group as an educational audiologist or in your clinic? Where you are bringing children of the same age to discuss everyday experiences. The children will tell each other what their issues are. They will tell each other the solutions that they have, and they are often better at it than we are. We need to reinforce this everywhere.

Provide information. The student needs to have a regular audiogram on file. The hearing test and reports need to be shared with all parties involved after a release is signed by the parents.

Team approach. As community and educational audiologists, we have to be on the same page. We have to think about what our team approach is and provide information to one another about the student. We have to acknowledge that the district has a responsibility to provide agreed-upon services to the student and that should be based on evidence, yet open to being modified.

Putting the child at the center. Families are the experts of their children, not us. Not all families have the same degree of internal motivation, and we have to be accepting of that. There will be instances where the parents do not show up for the IEP meeting. Thus, we have to partner with social workers, psychology, early intervention, teachers or speech pathologists. We have to address the needs regarding schedules and financing and consider how could a clinical and educational partnership support these needs. Both educational and clinical audiologists need to consider the result. The role is to influence change, not to make the change. We provide resources and lead the way. Many families that we interact with might not know about brain development. Not every parent knows that reading to their child, especially a child with hearing loss, is going to make a change.

Asking positive questions/rephrasing. Our first job is to get information, not to give information. We need to consider how to engage in difficult conversations with parents, educators, and the child. What if an educator makes it clear they do not want to wear an FM system? What if they make it clear that they do not want to make accommodations for these children? I think it is essential to ask these questions and be upfront about engaging the conversation. Community audiologists have to trust the educational audiologists and vice versa. This idea was adapted from How to Be an Effective Influencer for Good (Smith, Elder & Wolfe, 2015). Great article that discusses how we influence things. Another helpful tool is the Ida Institute, which is free to access and has amazing pediatric tools available.

Developing family-centered goals. Copy and paste the link into the browser: https://idainstitute.com/tool_room/pediatric_audiology/ The Ida Institute is a free resource that you can provide to parents with amazing tools. Anybody who wants to join can join, and it's got a beautiful international perspective. They have some incredible pediatric tools.

Auditory Issues in the Classroom

Vestibular

At least 40% of children with hearing loss are thought to have concomitant vestibular issues. Many of these children are identified as being clumsy. Pediatric vestibular issues impacts reading, ability to participate in sports and physical education, and difficulty with postural control and vision. One of the significant causes of balance issues in school-age children is Otitis Media. Screening with the Vanderbilt Dizziness Handicap Inventory for Patient Caregivers or the Pediatric Vestibular Symptom Questionnaire can be done.

Tinnitus

When we are working with children, we should know about tinnitus. We do not know what the prevalence and incidence of tinnitus in children are because the question is not asked. We know that about 12% of the general pediatric population and up to 55% of children with hearing loss have tinnitus. We have people who tell us that it addresses their attention and their concentration. It makes it difficult to listen in school and read silently. Children sitting in a quiet classroom may be disturbed by tinnitus. I would like to share an experience with a patient I saw with tinnitus. Gracie is a child that was referred to me for APD. An incredible little girl who didn't have APD. When she came in, we asked her about a couple of case history questions which included tinnitus. She told us she had this ringing in her ears, and her parents about fell out of their chair. Nobody had ever asked her that before. When we're working with kids, we should ask this question. We fit Gracie with a couple of tinnitus devices, and she went back to school. She'd been identified as not very bright and having Attention Deficit Disorder and APD. Gracie is now a junior in high school and does well with hearing aids that work with her tinnitus.

Noise exposure. There are a growing number of teens with noise induced hearing loss. A recommendation is that in addition to current hearing screening frequencies, 6000 Hz be added to the standard screening in high school. With this additional screening, we can perhaps change their behaviors early on.

Resources for Parents

I wanted to end with talking about a few resources for parents. The Whose Idea is It is available for people in Ohio, but anybody can download it. Hands and Voices are going from state to state to train parent advocates. If you're having trouble finding a parent advocate or you want more information on this, contact National Hands and Voices, they will provide all kinds of information to you such as a guidebook.

References

A Guide to Parents Rights in Special Education: Special Education Procedural Safeguards Notice; Ohio Department of Education (2017).

Colker, R. (2017). Special Education Law in a Nutshell. West Academic.

Erber, N. (1982). Auditory Training. Washington DC: Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf & Hard-of-Hearing.

Leavitt, R., & Flexer, C. (1991). Speech degradation as measured by the Rapid Speech Transmission Index (RASTI). Ear and Hearing, 12(2), 115-118.

Lidén, G., & Harford, E. R. (1985). The pediatric audiologist: from magician to clinician. Ear and hearing, 6(1), 6-9.

Smith, M. S., Smith, J. T., Elder, T., & Wolfe, J. (2015). How to Be an Effective Influencer for Good. The Hearing Journal, 68(6), 32-34.

Citation

Whitelaw, G. (2018). School audiology and community audiology partnerships. AudiologyOnline, Article 23846. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com