Editor's note: This text-based course is a written transcript of the live seminar, "Strategies for Clinical Teaching," presented by Joanne Schupbach, M.S., M.A., Manager Audiology Clinical Education, Assistant Professor, Rush University Medical Center.

The course handout is available here (PDF) - it is recommended to download the course handout prior to reading the text course.

In my role here at the university, my interests have focused on clinical education including clinical teaching, supervision and mentorship. Today I would like to share some information with you regarding what makes a positive learning environment and specific strategies that can be used in clinical teaching. Rush University is a multidisciplinary health care institution. Much of what I have learned about clinical teaching has come from evidence in other areas of health care including nursing, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and medicine. These disciplines have considerable literature and evidence on the critical aspects of clinical training including ideal preceptor qualities, what makes a positive learning environment and teaching rubrics. Some of what I will discuss may not be new to you, but I hope that you will glean some useful information on specific strategies and how you might include them, to modify or add to your current teaching skills. By the end of the session I will have identified some key elements for a positive learning environment as well as some teaching strategies that enhance student learning. I will also discuss effective teaching techniques based upon the student's level of learning.

Clinical Teaching Goals

Clinical preceptors have a great responsibility when training students and often this training takes place in a fast-paced, high workload environment. Catherine Burns, a Ph.D. nurse and her colleagues, Beauchesne, Ryan-Krause, and Sawin (2006) wrote an excellent paper entitled "Mastering the Preceptor Role - Challenges for Clinical Teaching". They proposed these goals for the clinical learning experience:

- Increase students' knowledge and skills

- Refine practice efficiency and effectiveness

- Promote increasing clinical independence

- Prepare students for optimal health outcomes with patients

- Become a competent, compassionate, independent and collaborative clinician

This is quite a mandate for all of us. Other nursing colleagues have stated that "nursing is a practice discipline with an appreciable amount of nursing theory originating in practice" (Craddock, 1993, p. 217-224; Phillips, Davies, Neary, 1996a, p. 1037-1044/1996b, p. 1080-1088). Others have said that "learning the art and science of nursing is a complex, intricate process, demanding competence that is highly cognitive and firmly rooted in practice" (Taylor & Care, 1999, p.31-36. I think you could easily substitute the word "audiology" for "nursing" in these statements and they would be equally accurate.

Positive Learning Environment

With these goals in mind, let's discuss what makes a positive learning environment. The 2005 Audiology Education Summit Report includes this comment, "Preceptors must understand that those assigned for practicum are students and appreciate the tentativeness and peculiarities of a clinician in training" (ASHA et al., 2005). This is an excellent statement to set the tone for an optimal experience. I like the term peculiarities. The diversity of members in any group adds to the richness of the experiences. Students' personalities and skill sets are all different as are those of their preceptors. Both the preceptor and the student need to demonstrate an appreciation and respect for these differences. Yonge, Krahn, Trojan, Reid, and Haase (2002, p 22 - 27) authored an article entitled "Being a Preceptor is Stressful" and made this comment, "A positive tone from the site professionals and staff is imperative from the outset for the student to feel welcome and nurtured." They found that in environments where preceptors and staff valued students, reflective practice increased. Valuing a student enhances a preceptor's openness and respect for the student's perspectives. The more positive that relationship is, the more positive the staff views the student.

We all understand well the importance of staff on practice efficiency. Sometimes staff can make or break an office. Ohrling and Hallberg's (2000) study of nurses' experiences as preceptors revealed several main ideas with "trust" as key. Preceptors needed to value the student's responsibility, and by spending time together they were able to develop the mutual understanding. The preceptors felt that once trust was established, they were able to extend the student's responsibilities. Effective and positive learning climates require trust as well. Most of us learn and perform best when there is an open, honest, respectful, caring and trusting climate. Students also do best when they are able to explore new ideas, and reflect on their work in thoughtful and meaningful ways without fear of judgment of reprisal.

In Reilly and Ormann's text Clinical Teaching in Nursing (1992), they pointed out other qualities of a positive learning environment. They noted that preceptors' demonstration of sensitivity and caring indicated to the student that the preceptor was really committed to helping the student achieve the desired outcomes. They also noted that if a student was fearful in the learning situation, the student became limited in his/her ability to think critically and to communicate well with the preceptor. Yonge and colleagues (2002) discussed that the preceptor's ability to value, work with, and support the student was essential for providing a climate that was conducive to critical thinking and one that promoted the student's inquiry.

The Yonge study also noted that preceptor preparation was the most important factor related to the success of the experience. If we consider our own preparation for taking on the role as a clinical teacher, it probably was not a very formal preparation. Yonge's group found that most preceptors felt unprepared for the role, particularly in the areas of teaching and assessment. This point reminded me of an article I had read a few years ago on new Ph.D's and teaching. The gist of the article was that most new Ph.Ds. hired in academic settings were given the responsibility to teach several new courses, yet most of them had never had any coursework in teaching. It's as if the Ph.D degree alone signified that the individual would be a good instructor. So if selection of preceptors is based solely on availability and education, and not on interest or ability, then the clinical education experience will likely be in jeopardy. Most preceptors are chosen based upon their experience level with the assumption that the individual is knowledgeable, skilled and able to handle the added responsibility. Most of us were not formally trained in supervision, but have learned teaching techniques and strategies through trial and error.

The conference report from the 2006 Audiology Education Summit divided preceptor qualities in the areas of preparation, experience, credentials, skills, knowledge, and personal characteristics (ASHA et al., 2006). These qualities are considered essential for high-quality mentorship. Also, the Summit's clinical education guidelines for audiologic externship discussed the aspects of a preceptor and of a training experience that are critical to a positive learning environment. These aspects included the preceptor's ability to: model best practices, provide timely feedback, uphold legal and ethical practices; facilitate personal and professional growth; promote skill building, and encourage lifelong learning. All of these relate to the clinical teaching goals discussed by Burns and colleagues; namely, that preceptors should assist the student's knowledge and skills, refine their practice efficiency and effectiveness, and promote increasing clinical independence.

Not only is preceptor preparation crucial but the 2005 Education Summit also noted the characteristics of the clinical site that are essential for a student's success (ASHA et al., 2005).

The equipment and physical environment were listed as important characteristics. Yonge, Myrick, Ferguson, and Lughana's article (2005) on promoting effective preceptorship agreed that physical environment is very important. Quiet and private space serves the experience well. Having private space for the student helps to reduce the overall distraction level of the high-paced clinical environment. Students need a place, even if it is a small space, in which to carry out their responsibilities as well as a place to quietly reflect on their clinical work. Remember that students are in a steep learning curve, and while fast-paced testing develops certain types of skills, it is not the best for integration of knowledge with clinical practice. Having private space to provide feedback is also a must. One thing that students do not like is to be called to task in front of others or patients. In addition to the physical environment, the other important characteristics of a quality clinical site noted by the 2005 Education Summit were: evidence-based practice; policies and procedures; adequate staff; site commitment; and diversity of experience.

When I asked a cohort of first-year students who had not begun clinical practicum what they expected from their supervisor, these were a sampling of their comments:

- Challenge the student's knowledge

- Allow some independence

- Allow room for error but expect improvement

- Provide encouragement

- Communicate with student

- Make expectations clear

- Show interest in student's growth

- Be approachable and not intimidating

- Give constructive, specific feedback

- Understand that students learn at a different pace and to exhibit patience

- Model best practices and be a good role model

- Assist student overcome feelings of nervousness, lack of confidence or feelings of being overwhelmed

- Develop trust in the student

Some of the expectations listed above mirror Burns' and colleagues' (2006) teaching goals of increasing knowledge and independence as well as allowing for mistakes to occur, but expecting improvement over time. The students also listed feedback as important as well as supervisor understanding that students learn at a different pace. Students noted that developing trust was critical for them. When I asked the students what they would not appreciate from their supervisory experience, these are some of their comments:

- Discrepancies across supervisors

- Assumption that the student knows something that is beyond what has been taught to date

- Supervisor who is distant or unwilling to fully facilitate student's work

- Supervisor too quick to correct a mistake or tell me what is the next step

- Distant or non-communicative supervisor

- Negative feedback discussed in front of a patient

Asking students what they expect from their supervisor and what they prefer not to happen is a good starting point to develop your teaching strategies with any particular student. Burns' group suggested these following teaching principles:

- Learning does take time and students, like us, learn at very different rates

- Learning is engrained with repetition, reinforcement, and with exposure to a variety of experiences.

- The more timely the use of the skills, the better the student's retention

The authors note: "The roles of the student, preceptor, and faculty must be intertwined to ensure for a good learning experience" (p.172-183). The student must also be a committed learner and the preceptor needs to tap into the student's needs and style of learning.

In the 2010 - 2011 Preceptor Handbook from the Department of Nursing at California State University at Fullerton, I found some key adult learning principles documented (California State University at Fullerton, 2011). For effective learning, the authors noted that the student must be ready to learn, involved in the process, and be focused and motivated. Learning must be interactive based upon the individual's needs, organized, and communicated clearly to the learner. Feedback should always be constructive, timely, and integrated with knowledge. The authors recommended that preceptors need to set expectations commensurate with the student's level of learning, use a variety of teaching tools to develop the student's skills, create a great environment for learning, and then constantly reflect on their supervision to determine their effectiveness.

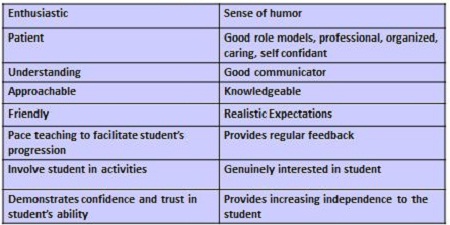

A longitudinal qualitative study by Gray and Smith (2000) in the Journal of Advanced Nursing examined the qualities of an effective mentor from the perspective of student nurses. They noted that there was a scarcity of empirical research that focused on mentorship. This study looked at a 1992 program of education that led to the diploma of higher education in nursing in the United Kingdom. The cohort was 10 students from the Scottish College of Nursing who were interviewed on five occasions over their three-year course of study. There were an additional seven students who volunteered to participate in the study and to keep a diary of their experiences. The focus of this study was to determine changes in the students' perspectives of the mentor over time. The key elements that these students felt good mentors exhibited are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Qualities exhibited by good mentors according to students, as per Gray & Smith (2000).

These qualities not only related to preceptor attributes but also to teaching strategies such as pacing teaching to facilitate the students' progression, setting realistic expectations, and providing regular feedback. Students' reports of what constitutes a poor mentor are found in Figure 2.

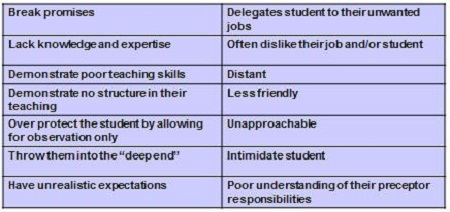

Figure 2. Qualities of poor mentors according to students, as per Gray & Smith (2000).

Once again these statements discuss supervisor attributes but also list ineffective teaching strategies such as demonstrating poor teaching skills, having no structure to the teaching, and setting unrealistic expectations. Generally the students with poor mentors coped by taking a philosophical stance by attempting to reduce the time spent with that particular preceptor and/or by discussing this with the educator at the end of their placement. At the end of the study, these same students were asked to reflect and comment on their future roles as preceptors. They were asked what they would do as a supervisor.

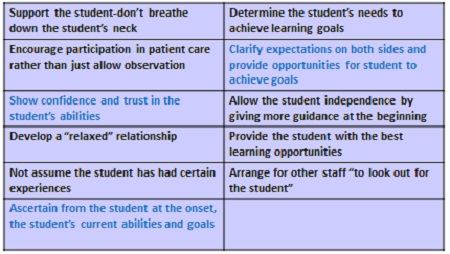

Figure 3. List of things students report they would do as a supervisor in the future, per Gray & Smith (2000).

As you can see from Figure 3, this list had less preceptor attributes and more strategies relating to teaching. Recurring themes included developing trust and confidence, determining the student's skill levels early on, setting expectations, and helping a student achieve goals by providing them diverse opportunities. Note that they also wanted "other staff to look out for the student's best interests."

Clinical Teaching

Teaching strategies have to be developed within the context of a given clinical setting as well as adapted to the level of the learner. Burns and colleagues (2006) surveyed a large number of nursing preceptors and these are some of the challenges that they noted.

- Rapid pace with multiple demands on the preceptor

- Teaching and learning is variable as cases vary in type, number, complexity

- Lack of continuity

- Limited time for teaching and feedback

- Learning may not be collaborative with preceptor

- Limited opportunities and time for reflection

- Learning may not be at an optimal pace for the student

These challenges seem to be similar to those we experience in audiology clinical practice. Our clinics also have a rapid pace and our cases vary in type and complexity. One of the comments I hear from preceptors, is that with the busy workload, time for teaching and feedback is also variable, which impacts the student's opportunity and time for reflection in learning. I think we would also agree that learning is not always at an optimal pace for students depending on the type of setting and the level of learner.

Categorized Levels of Learners

Burns and colleagues (2006) classified students into three categories - Beginner, Transitional Learner, and Competent Proficient, and noted some key points about each group. The Beginner student may do more observation initially, be given more routine and straight forward cases, and be assigned to prepare the basic components of a given evaluation. Some students will be very tentative at this level and require more nudging. Others may be very assertive even though they have very little experience. At the Transitional Learner stage, the preceptor may step back somewhat, have less need to provide input about the basics, give the student more complicated cases, and allow the student to decide on the key aspects of the evaluation. The Competent Proficient Learner has begun to develop solid skills in many areas, demonstrates improved clinical judgment, and can begin to generalize across patients. They are more flexible and integrative with their thinking and generally more efficient. At this point, the preceptor is allowing for more independence and the teaching strategy is to focus on pattern development and generalization across patients as well as to increase critical thinking.

Teaching Strategies

As we review specific teaching strategies, think about which ones you currently use and with which level of learner.

Modeling. With Modeling, the preceptor demonstrates the skills with patients as the student observes. Less experienced students begin to see the transition of classroom knowledge into the clinical setting. Although this is a strategy used with early students, using Modeling with more advanced students can also be beneficial. Advanced students can develop more integration of complex problems and issues, use critical thinking, and active listening. While this is a relatively passive strategy, it can be very powerful for all levels of learning. Modeling allows the preceptor and the student to act as a team through discussion of the case, development of a differential diagnosis, and making appropriate recommendations.

Case Presentation. Using the strategy of Case Presentation (Burns et al., 2006) allows for the student to obtain crucial information, apply it to the test battery, generate reasonable assumptions about the problem and develop a plan of action. It also allows the preceptor to assess the student's level of critical thinking and the ability to transfer previous experiences into new clinical situations. Case presentations are effective with every level of learner. The level of the sophistication of the presentation increases as the student gains more knowledge and experience. Also, the preceptor's expectation of the information presented will vary according to the level of the learner.

Collaborative Learning - Simulations. Collaborative Learning through Simulation (Gibbons et al., 2002) can be very effective, particularly with early students. The preceptor develops a case or selects a case, and the student works with the preceptor to discuss a possible case history, evaluation strategy, possible diagnoses, and recommendations. The student and the preceptor share in the decision making. This strategy can be used with all levels of learners, with straight forward cases for early learners, and more complicated cases for advanced learners. I like this strategy with beginners. I tell them that there is no wrong answer, but rather that this is a collaborative, brainstorming exercise. The preceptor may be more involved with the early learner in this strategy and take a step back with more advanced learners. For early learners, this is a positive, confidence-building exercise.

Sink or Swim approach. In Gray and Smith's 2000 article on the qualities of an effective mentor from the student nurses' perspectives, the Sink or Swim approach was criticized by students as suggestive of a poor mentor. However, in this strategy, ultimately the preceptor is responsible for the student's actions and is always available for consultation. This strategy might not be very effective with a beginning student, but would likely work well with a transitional student who needs some nudging to move their skills along, and certainly with a more advanced student. With an early student, the level of anxiety would probably be quite high if the student is given great independence with very little experience. Students who have been involved in this approach, even early students, have told me that while they did not necessarily appreciate the Sink or Swim approach, it did force them to rely upon their knowledge and skills, and to be confident in what they were doing.

Manipulated Structure approach. In contrast, the Manipulated Structure Approach (Gray & Smith, 2000) would be more appropriate for an early student. Here cases or procedures are carefully selected by the preceptor for the student's skill level in an effort to improve basic skills, to give the student early success, and to boost their confidence.

Reflection. Another teaching strategy is Reflection (Arseneau, 1995; DaRosa, 1997; Smith, 1997). As was noted earlier, reflection on one's performance is critical for learning. In a fast-paced environment, there is not much time given to reflection. We often expect students to make sense of everything quickly. Depending upon the level of student, they may need more time to reflect on the clinical details to understand how it all fits. They need to take the information, think about it, integrate it, and apply it to the appropriate patient or scenario. Even very advanced students complain about the lack of time to "make sense of things." Taking time to catch one's breath is important. In giving the student time to reflect it is imperative for them to be able to generalize information and to develop the crucial critical thinking skills necessary for more independent practice.

Self-directed Learning. In Self-directed Learning, the students develop their own goals, their own questions, and likely develop their own plan on how to accomplish these goals and questions. This strategy is likely most effective with transitional and competent proficient learners, those who have had more experience and better developed skills. Those students have a better understanding and judgment of their learning needs. Early students generally need more guidance with their learning. Often when you ask a beginning student what they want to learn, the list is endless, and not always relevant to the most important skill for their point in time of learning.

Self-assessment. Self-assessment is a skill that we begin teaching with early students. While initially, the self-reflection may not be very objective, over time the student learns to assess their strengths and weaknesses in their performance, and to develop their own strategies on how to improve upon them. Late learners do this on a daily and consistent basis, assessing each skill to refine their performance with little prompting from their preceptor.

Direct Questioning. Direct Questioning is an excellent technique to develop critical thinking skills, as long as the questioning is not perceived as a grilling. Questions, such as, "What do you think? What are some possibilities? Why do you think that? Give me an example. How could you handle that differently?" enable the student to share his/her observations and line of thinking. The preceptor can assist the student with formulating information based upon the answers to apply to other cases. This line of questioning also gives the preceptor a guideline about the student's ability to integrate information, formulate concepts, and to look at big picture issues.

Think Aloud method. The Think Aloud method, (Lee & Ryan-Wenger, 1997) as a tool of direct questioning, can be very effective. Both the preceptor and the student can provide rationale for specific questions and techniques that were used or will be used to demonstrate how conclusions were reached. The student basically describes their thought process or technique. This is a good method for developing critical thinking skills and can be used with all levels of learners. It is very effective with early learners as it forces the student to verbalize his/her thoughts and to support the decisions that have been made. The preceptor then has clear understanding of the student's ability to transfer knowledge to the clinical case, and their decision making process.

One-Minute method. The One-Minute method is a technique frequently used in medicine, particularly when time is short, thus the name. This technique has been written about by many authors and validated. In the One-Minute Preceptor Method (Neher, Gordon, Meyer, & Stevens, 1992), the student assesses the patient and then describes to the preceptor what is going on in a very brief time. The preceptor then challenges the student to provide supporting information to defend his/her assessment. The student is able to draw upon all resources and to critically assess the case. The preceptor then provides immediate feedback about what was correct and provides generalized information in which the student can apply to later cases. Here is how the one-minute method works with some learning goals. In this case, the student makes the decision regarding the case and the preceptor says, "What do you think?" Then the preceptor continues to probe for supporting findings and the critical thinking aspects by asking the student a question similar to, "What led you to that conclusion?" You then inform the student what the student was able to do well, followed by you as the preceptor correcting any errors or mistakes that the student did make. One aspect of this method that I use frequently is teaching the general principle by stating, "The key point I want you to remember is...". The last aspect of this method is the preceptor reflection and I use this as well. In addition to the student's thoughts I reflect about what I learned about my own teaching and we talk about what we both learned from this particular case. At the end of each case, I like to say to the student, "What is the most important point that you learned from this particular case?" That point may be different from what I think is the most important point, but it gives me the opportunity to understand what the student is gleaning from that particular experience.

Assigned Directed Readings. Assigning Directed Readings is especially good for early learners given the limited experience with certain kinds of patients, pathologies, and techniques. I like to use this with students both beginning and advanced. For example, you may see a patient with a rare pathology and ask the student to read a particular article, or research the subject and write a short synopsis. This gives an opportunity for the student to teach you, also. Generally later learners will do this on their own without prompting from the preceptor. A few weeks ago, I asked a beginning student to research the topic of hypothyroidism and its effects on hearing and learning in young children. The student needed to be directed to do this review while a fourth-year student would have had the inquisitiveness to do this without prompting

Coaching. With Coaching, the preceptor guides the student verbally through a test or procedure. The intent here is to keep the student safe and efficient with a technique they have not yet mastered. This is a strategy that we use frequently in our clinic as the students follow the clinicians' schedules and therefore may see a test or technique for which they have not yet had coursework. For example, my beginning student is currently enrolled in a vestibular course and is seeing VNG patients with me in clinic. I have done considerable coaching on equipment set up, running the computer, and giving patient instructions as the student does not yet have the knowledge or skill to complete the entire procedure.

Journaling. Journaling is a strategy that I use with my fourth year students as a way to stay informed about what they are doing at their site, and also as a way for them to express their thoughts about the week. Early in the year, the reflections are generally a run-down of the week. Later, their reflections become more of a collaborative thought process of what they have generalized over time and more about the big picture of their clinical work overall.

Feedback. Feedback is the final strategy I will discuss. Feedback is critical to the learning process. If no feedback is given, many students automatically think they he/she has not performed well. Without feedback, it is truly difficult for a student to make constructive change with his/her work. Allowing the student to provide their own self-assessment first is important for the student to learn objective self-assessment (Burns et al., 2006). Feedback needs to be descriptive and specific. Stating "You are doing fine," is not helpful feedback. Reinforce what is positive, discuss any errors or mistakes, and demonstrate to the student where they can improve. Students appreciate feedback that is delivered in a respectful and positive manner just like we like to hear feedback. On a busy day, it is really easy to forget about feedback as we are so focused on our patients' needs. We may sometimes forget that the student needs to hear some specific comments about how he/she has done with a particular patient or with a particular procedure.

Clinical Teaching Strategies Questionnaire

Kathleen Sawin, a Ph.D. nurse, was the lead author on an article entitled "Teaching Strategies Used by Experiences Preceptors" (Sawin, Kissinger, Rowan & Davies, 2001). In this article, they conducted a national survey of 265 experienced preceptors who were primarily nurse practitioners from 18 programs across the country. In the survey, they asked preceptors to identify strategies used frequently in clinical teaching. They used a tool called the Clinical Teaching Strategies questionnaire that was developed and validated in a series of studies by faculty and students in the School of Nursing at Virginia Commonwealth. They found that the preceptors identified a total of 65 total strategies, which were classified by frequency, use, and level of learner. They designated two levels of learners - early advanced beginners and late competent proficients. Almost half of the strategies, 29 or 45%, were used with all levels of learners, both beginning students and more advanced students. However, there were 36 strategies that did differ by level of learner. Strategies were categorized into five different areas: Orientation, History and Physical, Diagnosis and Management, Feedback and Evaluation, and General.

Let me provide a few examples of the 29 strategies used with all levels of students. In the area of Orientation, they assured all levels of students that there were no dumb questions. They also always shared their rationale for how they made a decision about any particular case that they were working on. They wanted to always promote a positive attitude about having students to train in their particular setting. Of the 36 strategies used with different learners, 26 of them were used frequently with both groups of learners. However there were substantial differences in the level of expectation used for each level of learner. For example, in the area of Orientation, advanced learners were expected to have the chart review completed and ready to discuss the case in detail. The advanced students were also held accountable for determining subtle changes during a patient exam and were expected to thoroughly discuss the appropriate intervention. While some of these strategies were used with early learners, the preceptor's level of expectation and sophistication was much lower for the early learners. Overall the study indicated that the 65 strategies were used most or all the time during clinical work. Those that were used less frequently appeared to be those that were more time-consuming or less directly related to the day-to-day practice.

Recommendations for Successful Preceptor-Student Experience

In the article on mastering the preceptor role, Burns et al. (2006) made some final recommendations to ensure for a successful preceptor-student experience. These were:

- Develop good pre-planning

- Brief interview prior to student's first day

- Discuss skill levels, goals, learning style

- Share your history and teaching style

- Review policies and procedures

- Delineate expectations clearly

I'd like to suggest my own list of recommendations based upon the evidence that I have reviewed over time. These are not in any particular order.

- Design student time with patients depending upon skill level

- Develop case presentation time

- Encourage discussion time (even if only a few minutes)

- Establish method of communication and regular meeting schedule with student (to discuss performance, learning, difficult cases, etc.)

- Develop experiences that encompass entire scope of practice

- Establish office space for student to perform duties and to reflect effectively

- Appoint lead preceptor who coordinates student learning and provides support

- Develop a structure for daily work

- Coordinate the student's clinical education with other preceptors

- Allow the student to follow through with each patient's entire procedure or treatment plan, if possible

- Ask student to establish goals and to self-evaluate during the experience

- Include student in continuing education activities

- Give student time to reflect on experiences

- Review student's evaluation and time lines from the academic training program

- Ensure that all preceptors are consistent with the training philosophy and procedures of your site (mixed messages undermine the success of the student's training)

- Evaluate your supervision periodically

As a reminder to all of us, students value and appreciate the following:

- Clear expectations for performance

- Helpful suggestions

- Immediate and specific feedback

- Honesty about their performance

- Praise

- Demonstrate respect for them and their value

- Encouraged to self-evaluate before the preceptor evaluates

Evaluating Your Own Supervision and the Teaching Strategies You Use

- Do you ask the student for feedback about your performance?

- Does your student complete a formal evaluation of your supervision?

- Does your student feel comfortable in providing feedback about your precepting?

- Would your student worry about retaliation if feedback was negative?

Some students will tell you what they need as the experience goes on. Others will not be assertive enough to do so, particularly early on, or will be concerned that the preceptor will take offense. Giving your student the ability and comfort level to provide you with feedback will enhance your mutual relationship.

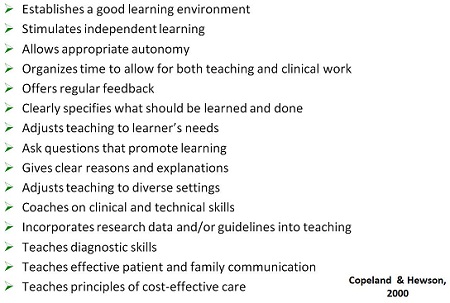

Clinical Teaching Effectiveness Inventory

The Clinical Teaching Effectiveness Inventory is a tool that may be helpful for evaluating clinical supervision. Copeland and Hewson, physicians from the Cleveland Clinic, developed this theory-based clinical teaching inventory to rate clinical teaching effectiveness (2000). The goal was to provide both positive and negative feedback to clinicians and educators in an effort to improve their teaching. This institution-wide instrument was designated to routinely evaluate all clinical faculty. It was tested for validity, reliability, and usability. The inventory has 15 items (shown in Figure 4) and uses a five-point Likert scale.

Figure 4. Items on the Clinical Teaching Effectiveness Inventory (Copeland & Hewson, 2000).

This seems to be a fairly easy and efficient tool that could be used in our settings in both a formal and informal manner. These are questions that you might ask of yourself informally or have the student complete the inventory. Many of these questions focus on key learning principles, for example, establishing a good learning environment, and stimulating independence and autonomy. Others focus on specific teaching strategies, such as allowing sufficient time for teaching and clinical work, giving feedback, asking questions, and adjusting your teaching style to the learner's needs. This tool or other similar tools can assist preceptors in focusing their attention on key issues that are necessary for an excellent clinical experience.

In my opinion, being able to objectively evaluate one's supervisory performance is as important as evaluating the student's performance. Allowing the student to provide you feedback without fear of reprisal will enhance the clinical education experience for the student and improve your teaching style. In the end, an excellent clinical experience benefits the student, the preceptor, and our patients.

Thank you for your attention.

How do we determine which of our staff would be good preceptors? Some people have an interest, but do not necessarily have the skills or experience, where others seem like they would be good preceptors and are not interested.

Generally I like to tell sites that determining who is really interested is key, and then determine what types of skills they have for precepting. Some preceptors, who may be earlier in their career, may feel that they do not have preceptor skills, but I think asking some of the questions that we have reviewed about their styles of teaching could be very helpful. Also I think since we do not have formalized training in clinical preceptorship taking extra courses in preceptorship or reading some of these articles that I have referenced can be helpful. I have provided these types of articles to sites that have been considering student supervision and also to sites that want to develop fourth-year externship programs. After reviewing some of the skills and strategies that preceptors need to have, people innately start to determine if they have those types of skills and abilities. For individuals that may have the skills and are not interested, I think it would be good to determine why that person or persons are not interested. It may be surprising to the administrator to find what those issues are. The number one thing I hear is that people do not have time with the demands on them in the health care environment now. I would counter that with a discussion about the fact that yes, students do take more time, but there are ways to work with students while maintaining our level of productivity.

Can you discuss the Audiology Education Summit? I have heard about it but do not know much of the details.

There were two Audiology Education Summits. They were held in 2005 and 2006. The 2005 Summit was sponsored by the American Speech, Language and Hearing Association (ASHA), the Council on Academic Accreditation (CAA) and the Council of Academic Programs in Communication Sciences and Disorders (CAPCSD). The 2006 Summit had these sponsors as well as the American Academy of Audiology. In attendance were invited academic and clinical educators from audiology doctoral programs as well as guests from clinical facilities and related professional organizations.

The goals were to look at what types of things were needed to develop clinical experiences for students in four-year Au.D. academic training programs. At the time of these summits, on-campus Au.D. programs were very new, and obviously the clinical education piece is a very important part of these training programs. Out of the summits came some wonderful reports on what we would expect to see in a preceptor as far as qualities and attributes, as well as what qualities were important for clinical sites such as depth and breadth of experiences covering the scope of practice, and sufficient space and resources for students. These reports were fairly comprehensive documents and if you have not had a chance to read them, I encourage you to do so. You can access them online: 2005 and 2006. They provide the nuts and bolts of criteria, A to Z, of what needs to happen to provide for a good learning environment for students in training. They cover not only what should happen on a short-term basis such as for second and third-year students that may be off campus two or three days a week, but also guidelines for developing long-term relationships with a student in your site, as with fourth year students.

From a clinical perspective, is there a tool or process used to validate that supervisors and preceptors are meeting the six characteristics described by the Summit?

I do not think that I have seen a tool or a checklist that would list all of those characteristics. Certainly the Summits made some recommendations about the preceptor needing to have between three to five years of clinical experience, a high level of skill, and high level of knowledge, and other characteristics but I am not sure that we have tools to actually measure that. As I said in my comment about PhDs . teaching courses but never having any coursework in teaching, the assumption is that we all have the knowledge and the ability to be a preceptor. The question we need to ask is, do we have the other characteristics and more formalized preparation to go down the path of being a preceptor and then to becoming a good preceptor? In my experience as an audiologist and over the years in my role at the university, I have learned a great deal about myself as a preceptor and how to change my teaching style based on the level of the learner or the student's needs. I don't think I have ever seen a tool that would help us ensure that all preceptors have these key components or even certain types of characteristics.

On average, how much time should preceptors expect to dedicate to a student including administrative activities?

Time can mean how often the student is at a particular site and the amount of time you spend with your student in a given day or period of time. The amount of time you spend with a student will be based upon the level of the learner. Also, when the student is new to your site and you do not know his or her skill level, initially you will spend more time with the student. Initially, you will want to see how the student works, not only performing test techniques and interacting with patients, but you will also want to determine their level of ability to critically think, integrate information and generalize. Some of our preceptors know that they can be committed to a student two days a week versus others who can handle students full-time and are best prepared to handle a fourth-year student.

If you were to be a site or a preceptor who said you had a student two days per week and you were the only preceptor, in early learners, the goal is that you are with the student most of the time. Early learners will follow your schedule of patients. As the student becomes more skilled and knowledgeable, and is able to become more independent, you can step back a bit and not spend quite as much time in direct supervision. I have talked with many preceptors over many years and find the amount of time spent depends upon the preceptor and the student. Some preceptors like to spend more time in direct supervision, even with students who are more advanced. Some preceptors like to step back more once they have seen the student has achieved a certain skill level with a particular technique or has abilities to work with certain types of patients.

Regarding your point about lack of training for preceptors, should Au.D. programs have coursework in supervision? Currently only University of Pittsburgh does.

I do agree that Au.D. programs should have coursework on supervision. Our university is in the midst of a curriculum review and is seriously considering a course to look at all aspects of supervision such as supervision of students, but also administrative supervision such as supervision of other personnel. I think it is critical that we receive some kind of formalized training in supervision if the expectation is that we as clinicians will be asked to train students. The starting point needs to be at the university. We need to be committed to the fact that training students on how to become future excellent preceptors is critical to their education. In an education setting, trying to add coursework into a program means that you have to take away some hours in other coursework. This is always a difficult challenge for universities.

Apart from specific skills and experiences, what guidance can you provide on matching students to preceptors?

When we talk about matching, we can talk about matching personalities as well as matching a student who has less experience in certain areas with someone who is an expert in that area. When I place students in off campus sites or even on campus, I might decide a particular first-year student needs to work with a particular supervisor first. This could be due to the experiences the student will get, or because of personalities. In the end, I like to take personality out of the picture. We all have very different personalities and trying to match people's personalities may not accomplish anything. The key point is having a preceptor that is willing, excited, and looking out for the student's best interests. There have been some cases where I have had sites who have said that they have designated a preceptor next quarter for a student, but the person is not really happy about being a preceptor. I say to the site that is probably a disaster waiting to happen. Everyone has to be onboard and excited about the relationship, in order for the experience to be successful.

How do you reconcile differences in practice techniques for procedures for which there are no standards, but preferences, such as masking?

I think you have to look to the evidence of what is best practice. As preceptors we all have different ways of doing things. Truly this is not a bad thing. Students learn a great deal from that. In a setting where there are several audiologists, a student may have three preceptors who do things three different ways. It can be confusing, however, if the student is told one day it is okay to do a technique one way, and the next day with the next preceptor that it is not okay. When it comes to procedures where there is no standardization, I think we have to look for best evidence for best protocol. When we have looked at our protocols, which we do usually every two years, we go back to the literature and review what is the highest level of evidence and then develop our protocols based on that. In your particular setting, one of the best things you could do is to develop your own protocols so that all your staff are on the same page. I have had sites ask if I would send them our protocols which I gladly do, but I always say that they are based on the evidence and the research that we have done. This can be a starting point for you, but it is in everyone's best interest to have best-evidenced protocols set your standards for your particular site. When there is no specific protocol, this becomes very confusing for the student.

Arseneau, R. (1995). Exit rounds: A reflection exercise. Academic Medicine, 70, 684-687.

American Speech-Language and Hearing Association (ASHA), Council on Academic Accreditation in Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology, & Council of Academic Programs in Communication Sciences and Disorders. (2005, January). Audiology education summit: A collaborative approach. Conference report from conference presented in Ft. Lauderdale, FL. Retrieved from: www.asha.org/uploadedFiles/events/audsummit2005.pdf

American Speech-Language and Hearing Association (ASHA), Council on Academic Accreditation in Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology, American Academy of Audiology, & Council of Academic Programs in Communication Sciences and Disorders. (2006, January). Audiology education summit II: Strengthening partnerships in clinical education. Conference report from conference presented in Ft. Lauderdale, FL. Retrieved from: www.asha.org/uploadedFiles/events/audsummit2006.pdf

Burns, C., Beauchesne, M., Ryan-Krause, P., & Sawin, K. (2006). Mastering the preceptor role: Challenges of clinical teaching. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 20, 172-183.

California State University-Fullerton Department of Nursing. (2011). Preceptor handbook, 2010 - 2011. Retrieved from: nursing.fullerton.edu/

Copeland, H. & Hewson, M. (2000). Developing and testing an instrument to measure the effectiveness of clinical teaching in an academic medical centre. Academic Medicine, 75(2), 161-166.

Craddock, E. (1993). Developing the facilitator role in the clinical area. Nurse Education Today, 13, 217-224.

DaRosa, D., Dunnington, G., Stearns, J., Ferenchick, G., Bowen, J., & Simpson, D. (1997). Ambulatory teaching "lite": less clinic time, more educationally fulfilling. Academic Medicine, 72, 358-361.

Gibbons, S., Adamo, G., Padden, D., Ricciardi, R., Graziano, M., Levine, E., & Hawkins, R. (2002). Clinical Evaluation in advanced practice nursing education: Using standardized patients in health assessment. Journal of Nursing Education, 41(5), 215-221.

Gray, M., & Smith, L. (2000). The qualities of an effective mentor from the student nurse's perspective: Findings from a longitudinal qualitative study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32, 1542-1549.

Neher, J., Gordon, K., Meyer, B., & Stevens, N. (1992). A ï¬ ve-step "microskills" model of clinical teaching. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice, 5, 419-424.

Ohrling, K., & Hallberg, I. R. (2000). Student nurses' lived experience of preceptorship. Part 2-the preceptor-preceptee relationship. International Journal of Nursing Students, 37, 25-36.

Phillips, R.M., Davies, W.B. & Neary, M. (1996a). The practitioner-teacher: A study in the introduction of mentors in the preregistration nurse education programme in Wales. Part 1. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 23, 1037-1044.

Phillips, R.M., Davies, W.B. & Neary, M. (1996b). The practitioner-teacher: A study in the introduction of mentors in the preregistration nurse education programme in Wales. Part 2. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 23, 1080-1088.

Reilly,D., & Oermann, M. (1992). Clinical teaching in nursing education (2nd ed.). New York: National League for Nursing.

Ryan-Wenger, N., & Lee, J. (1997). The clinical reasoning case study: A powerful teaching tool, Nurse Practitioner, 22(5), 66-104.

Sawin, K. , Kissinger, J., Rowan, K. & Davies, M. (2001). Teaching strategies used by expert preceptors. National Academies of Practice Forum: Issues in Interdisciplinary Care, 3(3), 197-206.Smith, I. (1997). The roles of experience and reflection in ambulatory care education. Academic Medicine, 72, 32-35.

Taylor, K.L. & Care, W. D. (1999). Nursing education as cognitive apprenticeship: A framework for clinical education. Nurse Educator, 24(4), 31-36.

Yonge, O., Krahn, H., Trojan, L., Reid, D., & Haase, M. (2002). Being a preceptor is stressful! Journal Nurses Staff Development, 18, 22-27.

Yonge, O., Myrick, F., Ferguson, L., & Lughana, F. (2005). Promoting effective preceptorship experiences. Journal of Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nursing, 32(6), 407-412.