Editor’s note: This text-based course is a transcript of the webinar, How to Advocate for Educational Audiology, presented by Kym Meyer, MS, CCC-A.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, learners will be able to:

- Identify services that an educational audiologist can provide.

- Name ways that an educational audiologist can collaborate with other school professionals, including the teacher of the deaf, speech-language pathologist, special educators, and clinical audiologists.

- Identify the laws that support access to educational audiology.

- Identify resources to advocate for educational audiology services in their area.

Introduction

Thank you for joining me for today's session on advocating for educational audiology. It's essential that clinical audiologists and parents partner together to advocate for educational audiology services. Parents can make an effective change when they know what to advocate for. Parent advocacy is the reason that special education laws were passed in the 1970s. Today, we will take a look at these special education laws, more specifically, the Individual with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). The overall message I'd like everyone to take away from this presentation is not to accept when schools say, "We don't have that service here." There are ways to advocate to make that service happen.

In 2018, Page and colleagues at Boys Town National Research Hospital conducted a multi-site, longitudinal study of children with mild to severe hearing loss. The study was named the Outcomes of Children with Hearing Loss (OCHL). Data was collected from 370 children (preschool age through 4th grade) in sixteen states (Page et al., 2018).

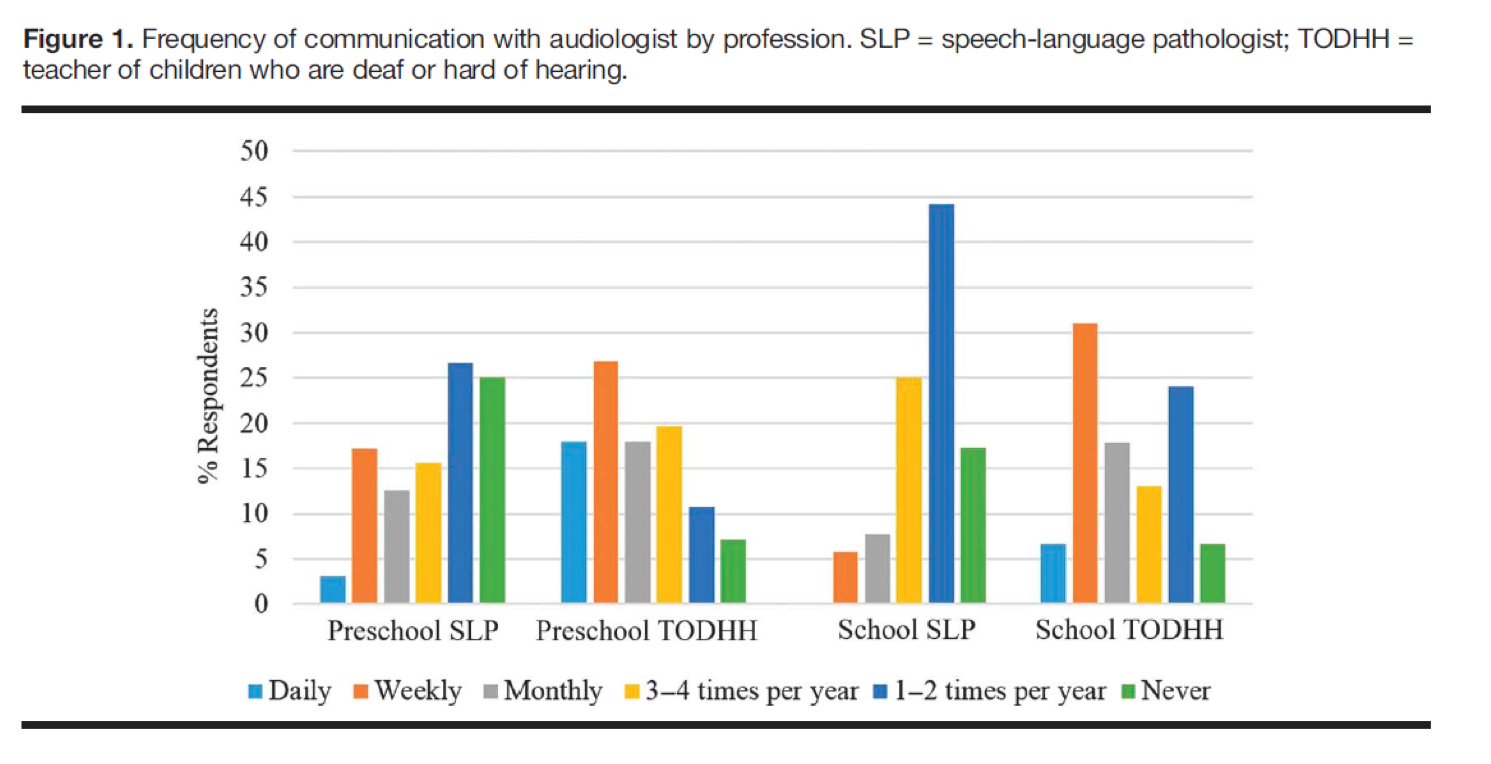

Figure 1 shows a graph that depicts how often speech pathologists and teachers of children who are deaf and hard of hearing (TODHH) communicated with audiologists. The data is separated into preschool and school-aged children, and whether the respondent was an SLP or a TODHH.

Figure 1. Frequency of communication with audiologists by profession (Page et al., 2018).

The color key is as follows:

- Light blue = Daily interaction with an audiologist

- Orange = Weekly interaction

- Gray = Monthly interaction

- Yellow = 3 to 4 times per year

- Dark blue = 1 to 2 times per year

- Green = Never

It is important to note that access to audiology services is quite variable. For example, according to this study, 20% of SLPs working with school-aged children reported never having an interaction with an audiologist. About 25% of SLPs working with preschool children indicated that they never had an interaction with an audiologist. For children in public schools who are hard of hearing, we need to make sure that they are receiving the proper audiological services.

The Outcomes of Children with Hearing Loss Study also examined evidence-based hearing aid fitting and verification measures, as well as the tracking (with data logging) the amount of time that children were using their hearing aids. They found that 30% of hard of hearing children had hearing aids that were not fit to optimize speech perception. It is essential that clinical and educational audiologists work together to ensure that hard of hearing children are consistently wearing their technology and that audiologists who are doing hearing aid fittings are using evidenced-based hearing aid fitting practices. The challenge is when we don't have an audiologist in the schools, we're not sure if the child is wearing their hearing aids all day at school.

We're going to talk a lot today about school-based personnel, which includes teachers of the deaf and hard of hearing, educational audiologists, and speech-language pathologists. We will not only look at how they overlap, but we will also highlight the differences in each area of expertise. Additionally, we will define the scope of practice for each profession.

What Does the Law Say?

What laws cover students with hearing loss in schools? The first one we will review is IDEA or the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. This is a special education law. Students who qualify under IDEA will receive an individualized education program or an IEP. An IEP is for students who need specialized instruction. In other words, they need some aspect of their curriculum modified in order to access that curriculum. For students who don't need the curriculum modified, but they just need the ability to access the regular curriculum, those children would get a 504 plan. Section 504 is an anti-discrimination, civil rights statute that requires the needs of students with disabilities to be met as adequately as students without disabilities (known as an "access" law). School audiology services are available through both IDEA and 504.

I want you to be aware that audiology is outlined in educational laws as they relate to students with hearing loss. For students who qualify for an IEP, every state is required to submit the number of students with that disability to the federal government. Of all students on IEP's in the United States today, only 1% of them have a primary disability of hearing loss [CITATION NEEDED]. When we're talking about hearing loss in public schools, although 1% is a small percentage of the total number of IEPs, it is critical that school districts employ people with specific expertise in hearing loss, to supplement the knowledge of special education directors.

IDEA: Section 300.34 (Related Services)

The first regulation from IDEA that we're going to review is 300.34, which is Related Services. Related Services means "transportation and such developmental, corrective, and other supportive services as are required to assist a child with a disability to benefit from special education." Such services include speech pathology, occupational therapy, physical therapy, nursing, and audiology services, among others. These related services are for all children with disabilities, not just children with hearing loss. If the child with disabilities needs related services to access the curriculum to receive Free and Appropriate Public Education (FAPE), the school district needs to examine this list to determine which of these related services the child needs.

As we know, children with hearing loss do need audiology services. Section 300.34 defines audiology to include:

- Identification of children with hearing loss

- Determination of the range, nature and degree of hearing loss, including referral for medical or other professional attention for the habilitation of hearing

- Provision of habilitative activities, such as language habilitation, auditory training, speech reading (lip-reading), hearing evaluation and speech conservation

- Creation and administration of programs for the prevention of hearing loss

- Counseling and guidance of children, parents, and teachers regarding hearing loss; and

- Determination of children's needs for group and individual amplification, selecting and fitting an appropriate aid, and evaluating the effectiveness of amplification.

This last part of the definition speaks to the idea of fitting hearing assistive technology, whether it is in the form of group amplification (i.e., FM systems or auditory trainers) or individual amplification (i.e., hearing aids). Any initial fitting of amplification needs to be done by an audiologist, as it is not within the scope of practice for SLPs or teachers of the deaf.

Even though audiology is a related service within special education law, the service delivery model varies widely. There's no predictable way of knowing what states or even what school districts offer regular access to educational audiology services. Some districts hire educational audiologists as employees. Other districts participate in collaborative organizations that might hire audiologists, such as the Board of Educational Cooperative Services (BOCES) in New York, the Intermediate Units (IUs) in Pennsylvania, or the Area Education Agencies (AEAs) in Iowa. Some hospitals and schools for the deaf have consultation programs where they contract educational audiologists to public schools.

IDEA: Section 300.5 (Assistive Technology)

Another regulation from IDEA I want everyone to be aware of is 300.5, the Assistive Technology regulation. This is the regulation for all disabilities, but it's important to note that hearing loss falls under this category. Assistive technology means any item, piece of equipment or product to improve the functional capabilities of a child with disabilities. For a child with hearing loss, FM systems and remote microphones would be considered hearing assistive technology (HAT). Closed captioning would also qualify as assistive technology. The term does not, however, include a medical device that is surgically implanted. In other words, school districts will not be responsible for mapping cochlear implants. Aside from that, any assistive technology that the child needs in order to access the curriculum needs to be provided by the school district.

Scope of practice. Audiologists are the only professionals for whom fitting HAT is within their scope of practice. Making decisions and selections about hearing assistive technology and initial hearing aid fittings are not within the scope of practice for teachers of the deaf or SLP's, as these topics are not taught in their graduate training programs. However, our teachers of the deaf and speech-language pathologists are often asked by their special education directors to determine what type of HAT devices to order and then perform initial HAT fittings on children. Many times, especially in districts where educational audiology is scarce or not available, teachers of the deaf and speech pathologists are afraid to say no, even though they have not been trained on HAT fittings. One comparison I like to use is that as an audiologist, I'm not qualified to do a swallowing study, because it's not within my scope of practice.

Similarly, an SLP should not be fitting HAT devices, as it is not within their scope of practice. Those conversations need to take place. Recently, I came across a teacher of the deaf Facebook page where one individual was asking other teachers of the deaf how to add hearing assistive technology to a CROS hearing aid. This is not okay, and coming up later in the presentation; I'll share some stories and examples of why it's not okay.

Collaboration is key. Children with hearing loss need all of these professionals (the educational audiologist, the teacher of the deaf and hard of hearing, and the speech-language pathologist) to collaborate within the schools. Although there is some overlap in what all of these professionals do, there are specific jobs for which each profession is responsible. Next, I'm going to share some resources that can help to facilitate this collaboration, and I will also outline some of the overlapping and collaborative roles. Links to these resources will be available in the handouts for this course.

The website Raising and Educating Deaf Children offers policy and practice eBulletins. For their April 2017 bulletin, I wrote an article titled "Separating the Roles of Teachers of the Deaf and Educational Audiologists" (Meyer, 2017). In addition, this particular bulletin refers to many other documents from the Educational Audiology Association, as well as from ASHA. On that website, you can access many documents on how to advocate for educational audiology services.

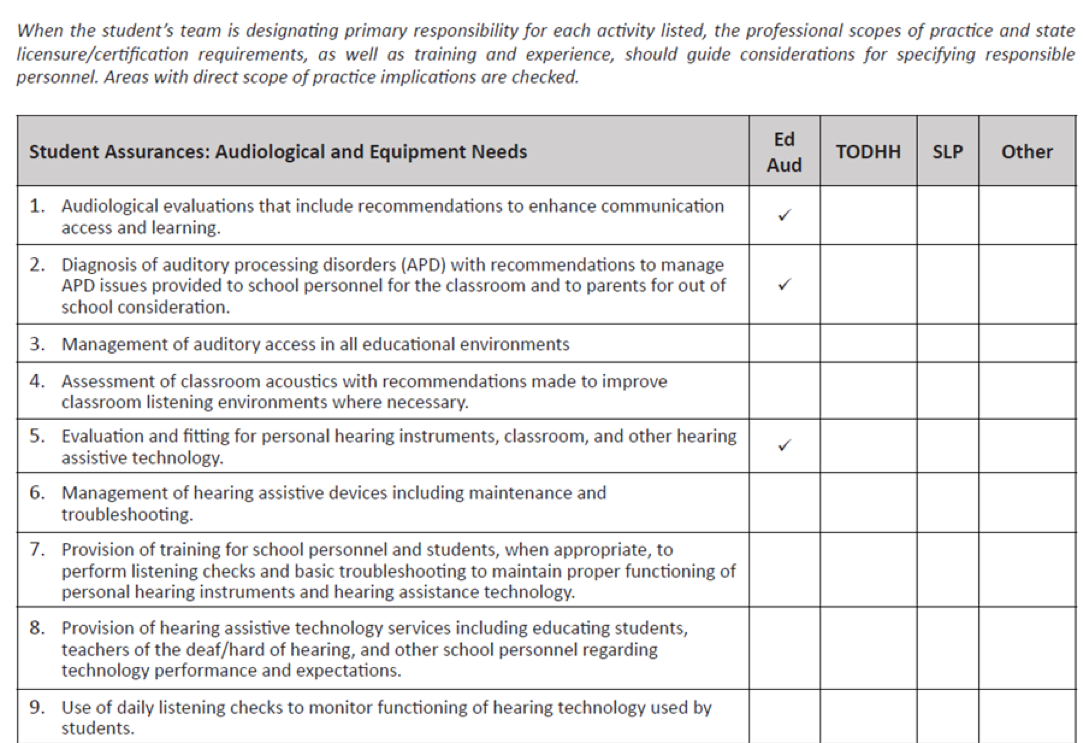

The Educational Audiology Association created a multi-page document titled the "Shared and Suggested Roles of Educational Audiologists, Teachers of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, and Speech-Language Pathologists". This collaborative document was developed to determine the scope of practice for each profession within the schools and outlines the types of services and support that children with hearing loss need. This document can be found on the website (www.edaud.org) when you select the Resources tab, then click on Position Statements.

Figure 2 shows the first page of this document. On this list, there are separate columns for educational audiology, teachers of the deaf and hard of hearing, and for speech-language pathology. For each category, you would check the box to indicate which professional would be responsible for providing each service. Note that in Figure 2, some of the boxes are not checked. As an example, the number 6 need is "The management of hearing assistive devices including maintenance and troubleshooting." Who would do that throughout the day? If a child has a speech pathologist that they see every day and the speech pathologist knows how to check the equipment, then we would check the SLP box in that setting. You can take this document to an IEP meeting and say, "The child needs all of these services done -- who is going to be the person responsible?"

Figure 2. Shared and suggested roles of educational audiologists, teachers of the deaf and hard of hearing, and SLPs.

Notice that in the Educational Audiologist column, there are checkmarks in these three areas:

- Audiological evaluations that include recommendations to enhance communication access and hearing

- Diagnosis of auditory processing disorders (ADP) with recommendations to manage ADP issues provided to school personnel for the classroom and to parents for out of school consideration.

- Evaluation and fitting for personal hearing instruments, classroom, and other hearing assistive technology.

The checkmark means that the only person that can provide each of these services is the educational audiologist. Likewise, you can go through this document and see the services that only SLPs and teachers of the deaf and hard of hearing can provide. Number nine indicates the "use of daily listening checks to monitor the function of hearing technology used by students". Routine checks of hearing aids and hearing assistive technology are required by IDEA, and we're going to talk about that next. I strongly suggest that you go to the Educational Audiology Association website and look at their position and advocacy statements as well because I believe that they can also help you in your advocacy for educational audiology services.

IDEA: Section 300.113 (Routine Checks)

Regulation 300.113 relates to the routine checking of hearing aids and external components of surgically implanted medical devices. This section dictates that on a routine basis, hearing aids and external components of surgically implanted medical devices need to be checked. Why did this regulation come into IDEA? Over the last several years, studies have been done showing that on any given school day, half of the children who used hearing aids had devices that did not work. We need to be checking technology regularly to make sure it is working so that students with hearing impairment have daily access to the curriculum. It is important to note that although the external parts of the cochlear implant need to be checked by the school district, it is not the school district's responsibility to pay for mapping or to send the child out for mapping. That is a parent's responsibility.

Who is responsible for checking this hearing equipment? If we don't have audiologists in the schools, it does not need to be an audiologist. I've trained school nurses, speech pathologists, principals, guidance counselors, special education teachers, and teacher aids how to check equipment. Not only do you need to teach one person within the school, but you also need to teach a backup person. If the primary person is absent, who's going to be the backup person to check the equipment? The person who is trained needs to be trained by someone who knows how to check hearing aids.

There are a number of different ways to appropriately check hearing assistive technology. Asking the child, "Can you hear me?" is not an appropriate way to check hearing assistive technology or hearing aids. If you ask a yes/no question, and the child says, "Yes," what does that mean? You don't know how well that technology is working. You don't know if the remote microphone is working. We want to be sure. In some cases, we need to have someone listen to the equipment, take the hearing aid off the child, listen to it, if they can't give some reliable feedback. Maybe move across the room from the student and ask them questions through their microphone. I like to play Simon Says. If I'm wearing their Roger microphone and they're across the room, I put my hand over my mouth so they can't lip read, and then I might say, "Simon says, 'Touch your nose,'" and make a game out of it. Another option is the Ling Six-Sound Test, which is another way to get children to repeat back sounds. If you type "Ling 6 Sound Test" into a search engine, you will find videos online that demonstrate how to do that.

If there is one thing we know in education, it's that if you don't write it down, it didn't happen. It's important that the person checking the HAT documents their daily checks. I often keep a spreadsheet to have them track the date, what they did and what they found. If everything is working, they get a checkmark. If the child was having problems, then the team needs to determine the plan of action if something goes wrong. If the child's equipment is not working, what are you going to do and who is going to take care of that? Be explicit with the process to make sure that the child can get up and running with their technology.

Several years ago, I worked on a team where we sent out a questionnaire to speech pathologists throughout the State of Massachusetts asking them about their comfort level about checking students' hearing assistive technology. About half of the respondents indicated that they felt comfortable checking HAT, and the other half stated that they were not comfortable (MA Department of Elementary & Secondary Education, 2006). In this questionnaire, we only asked for their self-reported comfort level. We didn't ask if they were competent or what they knew how to do. As such, we need to wonder who taught them, and do they know how to check hearing assistive technology? I've gone into enough situations where SLPs have told me they're confident, only to observe that they need a lot of support. In most schools, checking HAT often falls by default to the SLP. We need to be working with our SLP colleagues to let them know they are not in this alone. We need to give SLPs permission to admit that they need additional training and support in this area.

Educational Audiology and 504s. Students with permanent hearing loss who are not eligible for special education services under IDEA can still receive related services (educational audiology) and assistive technology (HAT) through a 504 plan. Through periodic monitoring, the educational audiologist can support communication access accommodations, including the use of assistive technology, as they pertain to the student's hearing loss. Children with any level hearing loss on an IEP or on a 504 can receive audiology support in public schools.

Real-Life Examples: HAT Checks Gone Wrong

In my experience over the last several years, I have encountered numerous situations where things have gone wrong when audiologists are not involved in hearing assistive technology fittings in schools. I'd like to share some of these example scenarios with you.

In one case, the hearing assistive technology (an FM system) turned a child's hearing aids off every time the speech pathologist attached the device. As a result, the child was unable to hear while he was at school and was in danger of failing. The speech pathologist began to fit the child's hearing assistive technology in September. I did not get called into the school district until the spring of the following year. Every single day when this child went to school, the receivers were shutting off the child's hearing aids, thereby acting as earplugs rather than enabling amplification. When I got the call, they told me that they wanted to take the child's FM off, because they said he performs worse while wearing it. I'm quite sad that it took seven months to figure out what was wrong. If an audiologist had done the initial fitting, that unfortunate situation would not have occurred.

In another situation, there were teachers who wore HAT microphones in the classroom, but they did not realize the children needed HAT receivers on their hearing aids. As we know, without the receivers, the child does not have access to the curriculum. The teacher thought the sound just magically traveled to the child's hearing aids. Similarly, in another scenario, one teacher had a sound field microphone around their neck when I walked into a classroom. I looked around for the speaker because I didn't hear it and I couldn't see it. I asked the teacher where the speaker was, and they were confused. As it turns out, we found the speaker in a closet turned off.

At one elementary school, for a six-week time period, teachers in three classrooms mixed up the microphones and receivers for three children. In other words, teacher A was talking to child B in child B's classroom, and child B's teacher was talking to child C in the next classroom. It took six weeks to figure out that something was wrong. Unfortunately, the students complained to the teachers, and they said nobody believed them.

This next situation occurs more often than I'm comfortable with. The school decided to use a sound field speaker system for a child with a significant hearing loss. This sound field system benefited all of the students in the room except for the child with hearing loss. Sound fields are great, and I'm a huge proponent of sound fields when it's appropriate, but for many children with more significant hearing losses, they need direct instruction with personal hearing assistive technology.

Resources to Advocate for Educational Audiology

Next, I'd like to share some resources with you so that you can advocate for educational audiology, both in your clinic and with your families as well. Before I highlight some of these resources, I would like to suggest that you include the following recommendation in your clinical audiology reports:

"Hearing assistive technology (HAT) is recommended to access the curriculum. Consultation in the school from an educational audiologist is recommended to select and fit appropriate HAT technology."

Even if they've never heard of educational audiology in your area, and even if your parents are complaining that they don't have access to educational audiology, put this recommendation in your clinical audiology reports. Special education directors and principals may not always understand that an educational audiologist is the correct professional to do this work. If you include this recommendation, even if you don't have those services in your area, it's going to start the conversation with parents and administrators. We did this in Massachusetts. I asked some clinical audiologists at some large hospitals to include this recommendation in their reports. Once they started doing that, the special education directors started calling each other, asking, "What do we do now? We have to get this service."

Wrightslaw is a free website that explains laws related to special education and 504 plans. Parent advocacy is how special education laws were initially passed in 1975. Parents got together and sued school districts, and those lawsuits in the early '70s went up to the Supreme Court, and that's how we got initial special education laws passed in 1975. Parents have a lot of power, but they often don't know what their rights are. This handout helps parents understand what educational audiology services are. You can print this handout and give one to every parent on your caseload so that they can advocate for educational audiology services within their child's schools. This document can also be given to clinical audiologists, as well we special education directors. Parents have told me that their Special Education director didn't know anything about audiology services until they received a copy of this handout. Again, don't simply accept the excuse, "We don't have that service here." That's not how special education works.

As I mentioned earlier, the Educational Audiology Association has a great advocacy document available on its website (www.edaud.org). The document is titled "Shared and Suggested Roles of Educational Audiologists, Teachers of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, and Speech-Language Pathologists." You can download and print this document and give it to parents to bring to their child's IEP meeting. I also strongly suggest that you go on this website to look at their position and advocacy statements that parents and clinical audiologists can use as well.

Another excellent resource is the book "Optimizing Outcomes for Students who are Deaf and Hard of Hearing." It was written by the National Association of State Directors of Special Education (NASDSE) and is in its third iteration. My personal goal is to get this book in the hands of every parent and every professional who works with deaf and hard of hearing children, including special education directors. It's available as a free .pdf and is included in the references section of this presentation.

At a conference I attended (Teacher of the Deaf Mainstreaming Conference), I wanted them to start thinking about the resources that they could use in their community to "nudge" the district into compliance with educational audiology services. I asked clinical audiologists to give out the Wrightslaw article to parents. I also challenged them to present to local parent groups about educational audiology services. Also, I encouraged them to tap into the local audiology community and asked them to include the recommendation I mentioned on the previous slide on every report. Finally, I encouraged them to be a resource to deaf and hard of hearing organizations. It's important that we have audiologists, teachers of the deaf, and SLP's continue to talk about what is and what is not within their scope of practice.

If a school district decides to hire an education audiologist, where do they find one? First, I would suggest that they contact the Educational Audiology Association (EAA) to ask them if there's already an educational audiologist in your area. That would be a great way to begin. Every state has an EAA representative, and that person would know what is happening within their state, so they can direct you if there's a possibility of providing services. Another way to locate an educational audiologist is to connect with other local families of children with hearing loss to find out if their children had access to an educational audiologist in their school district. Then, see if your district can contract with the other school to borrow their educational audiologist. Contact your state Commission for the Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing to see if they have any resources. Finally, you could contact a local university that trains audiologists to see if they can provide educational audiology services (although increasingly, AuD training programs are not providing instruction in educational audiology service delivery).

Support the Movement: #EdAudAdvocacy

The hashtag #EdAudAdvocacy was voted on at the mainstreaming conference a couple of summers ago. Now that social media is so prevalent; we can use this hashtag across social media platforms to educate parents and other audiologists about educational audiology services. I'm on several different Facebook pages, and I will often see either SLPs or teachers of the deaf ask, "What do I need to do with this hashtag?" I'll inform them of some of the things they can tell their special education directors, but then I always use this hashtag as I'm explaining things. Again, students with hearing loss represent only 1% of the population of children on IEPs. As such, we're not on special education directors' radar at all. Therefore, we need to be assertive to get them to understand the needs of our children with hearing loss.

Summary and Conclusion

The things I talked about today are not easy fixes. I do believe this is a movement. I believe that we need to be working together. The clinical audiologist, the speech pathology community, and parents, need to be pushing this along, because, without it, educational audiology will be overlooked as a service for children in schools. My peers who are working in public schools as educational audiologists are often fighting to keep their jobs. The service is important. Audiologists need to be the ones evaluating for and fitting personal hearing instruments, classrooms and other HAT devices. We also need to partner with other professionals in the schools. In the long run, our diligence and advocacy will prove beneficial to deaf and hard of hearing children.

Citation

Meyer, K. (2019). How to advocate for educational audiology. AudiologyOnline, Article 26090. Retrieved from https://www.audiologyonline.com